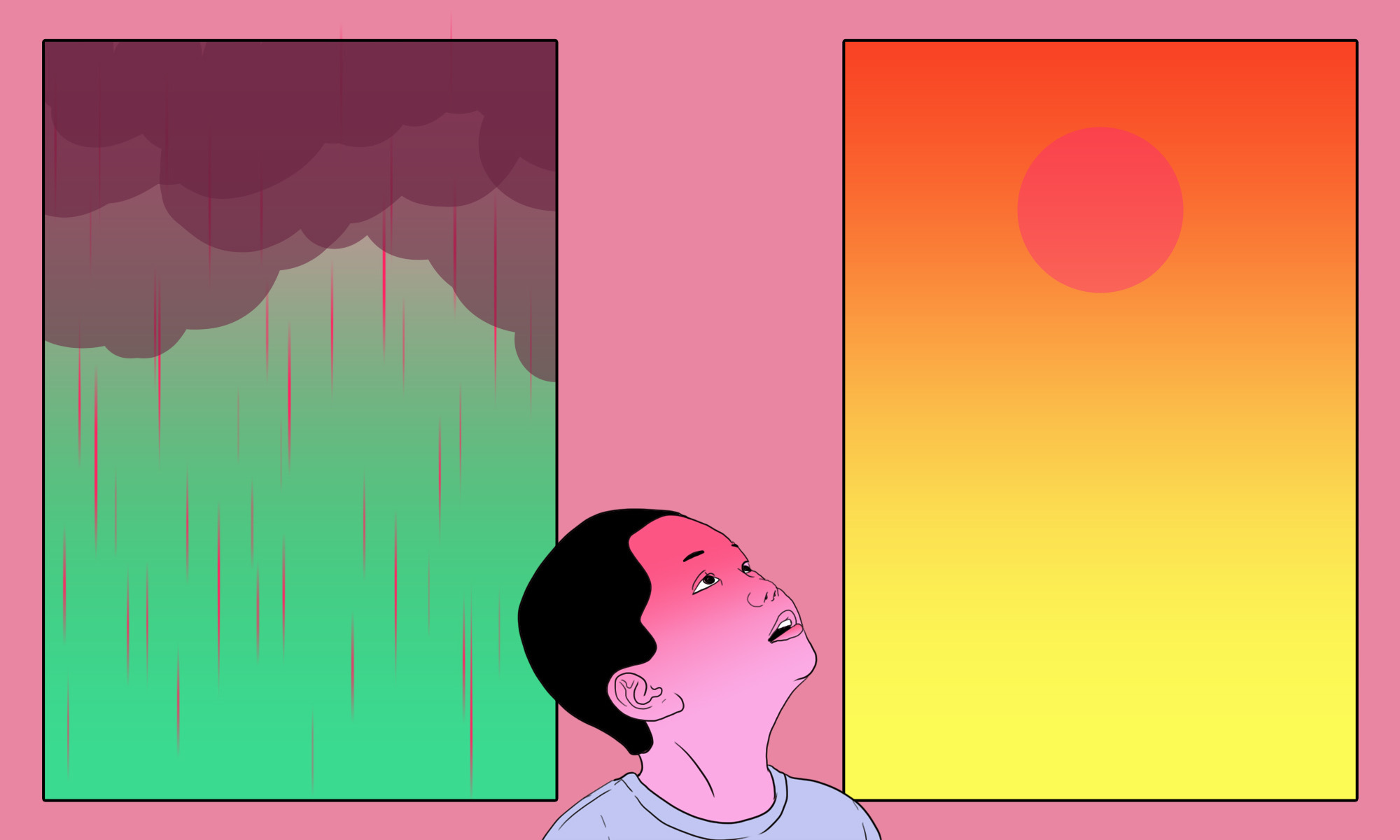

China’s plans for a summer of extreme downpours, floods, and heat waves

China is using artificial intelligence to forecast extreme weather events, but there is no relief in sight for a country that is particularly vulnerable to climate change.

A landslide left another two people dead and two others missing in a village in Gansu Province on July 10, Chinese state media reported yesterday. Seven people were injured, and a total of 336 people have been evacuated to a temporary shelter.

The people are the latest victims in a string of fatal extreme weather events that have brought anguish to local residents in China in the past few weeks. “Climate extremes, including flood, drought, and high temperatures, really cause a lot of risks to communities,” Faith Chan, the head of the School of Geographical Sciences at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China, told The China Project yesterday.

Floods

A deluge of rainfall and floods have sparked a number of landslides all over the country. At least four people were killed and five others are still missing after a landslide hit a highway construction site in central Hubei Province on July 8, Chinese state media reported yesterday. A separate landslide in a county in Sichuan Province left four people dead and three missing on June 27, leading authorities to evacuate over 900 people: As of today, more than 40,000 people in the region have been displaced because of floods.

In the neighboring southwestern municipality of Chongqing, two days of torrential downpours and flooding have left at least 15 people dead and four missing as of July 5, according to local authorities. Footage posted online showed a multistory building collapsed into a nearby river from the force of floodwaters, while other images show cars submerged in the streets.

A screenshot taken from video footage online.

Heat waves

While some parts of China were being battered by heavy rainfall, other regions have been sweltering in record-breaking heat. At least two people died due to heat waves in Hebei Province on July 7, while the peak temperatures at nine national weather stations in the region hit their record highs of up to 43.7°C this year.

On June 22, Beijing logged a record-breaking temperature of 41.1°C (106°F) for that month, and its second-highest temperature ever since modern records began. (The previous June high was 40.6°C [105°F] logged on June 10, 1961; the all-time high was 41.9°C [107°F] recorded on July 24, 1999.) The Chinese capital has seen temperatures rising above 40°C (104°F) for 11 days since 1951 — and five of them occurred over the past two weeks, according to CNN.

In some parts of the country, workers in offices, zoos, and train stations have resorted to putting out large blocks of ice to bring temperatures down.

The scorching heat will likely put more strain on the nation’s power grid, particularly during the peak energy consumption period over the summer. In May, the most recent data released by China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), hydropower capacity across the country dropped by about a third due to prolonged droughts.

Hydropower capacity in the provinces of Sichuan and Yunnan, China’s biggest hydropower exporters, fell by 24.4% and 43% in May compared with the previous year. Other hydropower hubs, including Hubei and Guizhou provinces and the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, also reported significant decreases ranging from nearly 50% to over 60%.

Those concerns have forced some regions to step up operations at coal-fired plants in an effort to ensure enough power to heat-stricken households.

The Chinese government steps up emergency response efforts

The extreme weather events have spurred Chinese authorities to launch emergency response measures and issue a string of warnings to local officials and the public, as skyrocketing temperatures and severe floods threaten to damage crops and strain the country’s power grids.

Chinese leader Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 last week called for stronger disaster relief efforts to protect people and property, while warning that all seven of China’s major rivers were at risk of flooding.

In the long term, “municipality governments should work closely with the National Climate Change Office and adopt ‘fit-for-purpose’ plans for coastal and inland cities because the conditions [vary],” Chan told The China Project. “The governments should also [make] the best use of big data and social media for disaster preparedness, responses, and recovery practices to improve climate resilience.”

Meanwhile, the country’s national observatory yesterday renewed its orange alert, its second-highest warning, for soaring temperatures across southern China and areas in the north and northeast. Under the warning, employers must place limits on outdoor work, though delivery workers for restaurants and online retailers are still working.

“China has implemented real-time release of early risk warning information and corresponding public health services in some pilot provinces and cities,” Chao Ren, associate professor at the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Hong Kong, told The China Project. “The number of provinces and municipalities across China that issued health risk early warnings related to climate change increased from two provinces and two municipalities in 2020 to eight provinces and 27 cities in 2022. But it is still not enough. To protect outdoor workers under extreme heat, the Chinese government, especially city governments, should create a localized warning system for them.”

It’s going to get worse for China

China is particularly vulnerable to climate change, with a warming rate higher than the global average and more frequent extreme heat events across the country, according to the Blue Book on Climate Change in China for 2023 (in Chinese) released by the China Meteorological Administration (CMA) on July 9.

According to the Blue Book, a total of 3,501 extreme heat events were recorded in 2022, the most frequent since 1961. The number of days of accumulated heavy rainfall (daily precipitation of or more than 50 millimeters) has also increased by an average of 4.2% every 10 years between 1961 and 2022.

Meanwhile, the average annual precipitation is on the rise, increasing 0.8% each decade during the same time period, while regional differences in weather patterns are intensifying.

A more climate-resilient society

The Chinese government has launched some policies to counter the effects of climate change. In May 2022, the country’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment announced its National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy 2035 (in Chinese) to help China build a more climate-resilient society over the coming years. It calls for greater efforts to ensure food security, strengthen early warning systems, and mitigate supply chain risks.

Developing technologies are also aiding efforts to guard against the impact of climate change. China’s National Meteorological Centre (NMC) has rolled out artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to help forecast typhoons up to 12 hours in advance, while Chinese cloud company Huawei has stated that it has developed an AI-based global weather model, Pangu Weather, that can provide faster and more accurate forecasts than previous methods.

“Changing climate and climate hazards have triggered compound and cascading impacts on human health in both the short term and long term, requiring more flexible and timely adaptation responses,” Ren told The China Project. “The Chinese government should put more effort and quick actions into adaptation, instead of only addressing climate change mitigation and carbon neutrality. Both adaptation and mitigation are equally important.”

However, China is but one of the many countries that are having to learn to cope with floods, droughts, extreme heat, and all the other consequences of the world’s changing climate. An intense heat wave is straining energy resources in Southern Europe and in India, heavy rainfall and flash floods are devastating areas in Japan and in the U.S. state of Vermont, while a growing number of extreme weather events often go unreported in countries in Africa.