China pressured Turkey to bust Uyghur bookseller

Is an Istanbul bookstore guilty of copyright infringement or cultural preservation?

Saving Uyghur literature for future generations was Abdullah Turkistanli’s mission when he opened a bookshop in Istanbul to sell texts now banned in China. Never did the 53-year-old exile imagine that Beijing could pressure Turkish police to raid his collection and threaten legal action to shut him down.

Turkistanli, a devout Muslim and a survivor of 13 years in Chinese prisons, is owner of the Kutadgu Bilig Bookshop in a basement in the suburb of Sefakoy, where exiled Uyghurs fleeing persecution by Beijing number at least 50,000.

Most of the Uyghur books he sells he prints himself from PDFs of the originals. Many of the authors whose words he is trying to preserve are in prison in northwestern China, the Uyghur homeland, where authorities continue a systematic clampdown on Turkic Muslim culture that began in earnest in 2016.

Chinese publishers are barred by Beijing from granting permission to reprint Uyghur books. Accusations of copyright infringement prompted by Chinese government pressure, Turkistanli suspects, caused more than 50 Turkish police to burst into his shop in August 2022, and again in March 2023, to cart off sackfuls of his 11,000 Uyghur books.

Poet Aziz Isa Elkun, General Secretary of the Uyghur branch of PEN International, the worldwide literature and free-speech advocacy association, said that despite a wish to uphold laws banning copyright infringement, Uyghur literature is in a class of its own and urged the Turkish government to “consider the reality of the Uyghur situation.”

“China is burning books,” Elkun told The China Project from London. “Uyghurs, as the original owners of these books, are trying to preserve them and share them with other Uyghurs.”

Escape

Hailing from Hotan in the south of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, an area in northwestern China roughly three times the size of France, Turkistanli first was accused of terrorism and arrested for reading his Quran in the early 1990s. His years in and out of jail took a toll on his mental and physical health.

When he got out for the last time, in 2008, Turkistanli knew there was no future for him in China. He wanted to continue practicing Islam and faced prohibitive fines for having several more children than China’s birth control law allowed ethnic minorities.

“My father said he would disown me if I didn’t leave the country,” Turkistanli told The China Project. “I refused for a while, but then I realized he was serious. I had to leave for my sake and also that of my wife and children.”

None of the traditional escape routes were open for a man with no passport. As a last resort, he hatched a plan to walk over the Tian Shan Mountains to Kyrgyzstan and take his chances in Central Asia. He set off alone, hoping his wife and their 11 children might join him once he was settled.

He made his way over treacherous passes with occasional help from shepherds tending their flocks in summer pastures. Instead of a welcome at the Kirghiz border, Turkistanli was arrested for illegal entry and imprisoned again without trial. Assuming he was a fugitive terrorist, Kirghiz officials called Chinese police.

“I was battered so hard my fingers were broken and my back severely damaged, but I had nothing to tell them,” he said. “I was not a terrorist.”

Attempts to break him failed and after a year in custody, Kirghiz officials told him he could buy his freedom with a $50,000 bribe. His family and friends back home in Xinjiang scraped up the cash and wired it over. In return, he was given a letter of passage to Turkey, where, in 2009, he immediately admitted himself to the hospital.

“I could barely walk when I arrived in Turkey,” Turkistanli said. In the years since, he has endured seven back surgeries and a two-year period of paralysis. He still has pain walking.

After an initial recovery, he opened a modest furniture shop in Sefakoy to make ends meet. In 2013, he hatched a plan to open a small Uyghur books library in the shop basement.

“I was shocked at how people were treating books,” he said. “They were even throwing them away. Uyghur literature is our life. We are losing our language and our writers are in prison. We must do everything we can to hold onto it.”

Turkistanli was determined to rescue every book he could from Istanbul’s Uyghur community. Word spread and Uyghurs who saw that the situation in Xinjiang was getting worse arrived at his shop in droves with cases full of books they’d carried out with them.

In 2014, Turkistanli’s wife, Amine, and eight of their children joined him in Istanbul. Three of their kids stayed behind, unable to get passports.

Book banning

In 2016, Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xí Jìnpíng 习近 promoted Chén Quánguó 陈全国 to the position of Party Committee Secretary for Xinjiang. Pumped up from the crackdown he led on Buddhist dissenters in neighboring Tibet, Chen quickly got to work.

Under Chen’s rule, a vast network of so-called reeducation camps was built in Xinjiang to “cure” the “ideological viruses” of separatism and religion besetting the minority Turkic population.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

Soon, authorities carried out mass arrests of Uyghur writers and poets, and banned their books. During the height of the persecution, Chinese police searched Uyghur villages house to house and detained anyone found in possession of a banned book. Most Uyghur academics were rounded up and either disappeared or put in jail for a long time.

“To be on the safe side, some people would just burn all their books,” Turkistanli said. “They never knew if something that was safe today would be the cause of them going to a camp tomorrow.”

As the clampdown in Xinjiang intensified, the exiled Uyghur community in Istanbul grew. Some estimate there are as many as 150,000 Uyghurs in Turkey today.

Turkistanli and Amine never heard from the three children they left behind in China. In Istanbul, the eight kids who made it out have been schooled equally. Some have completed university.

“My wife and I value education highly — both for boys and girls,” he said.

Soon, Beijing began to warn Ankara to look out for “dissidents” such as Turkistanli, people the CCP considered a danger to society.

In 2017, Turkistanli was arrested by the Turkish government. He was imprisoned without trial for a year. He was bankrupt and his bookshop closed.

Uyghur haven

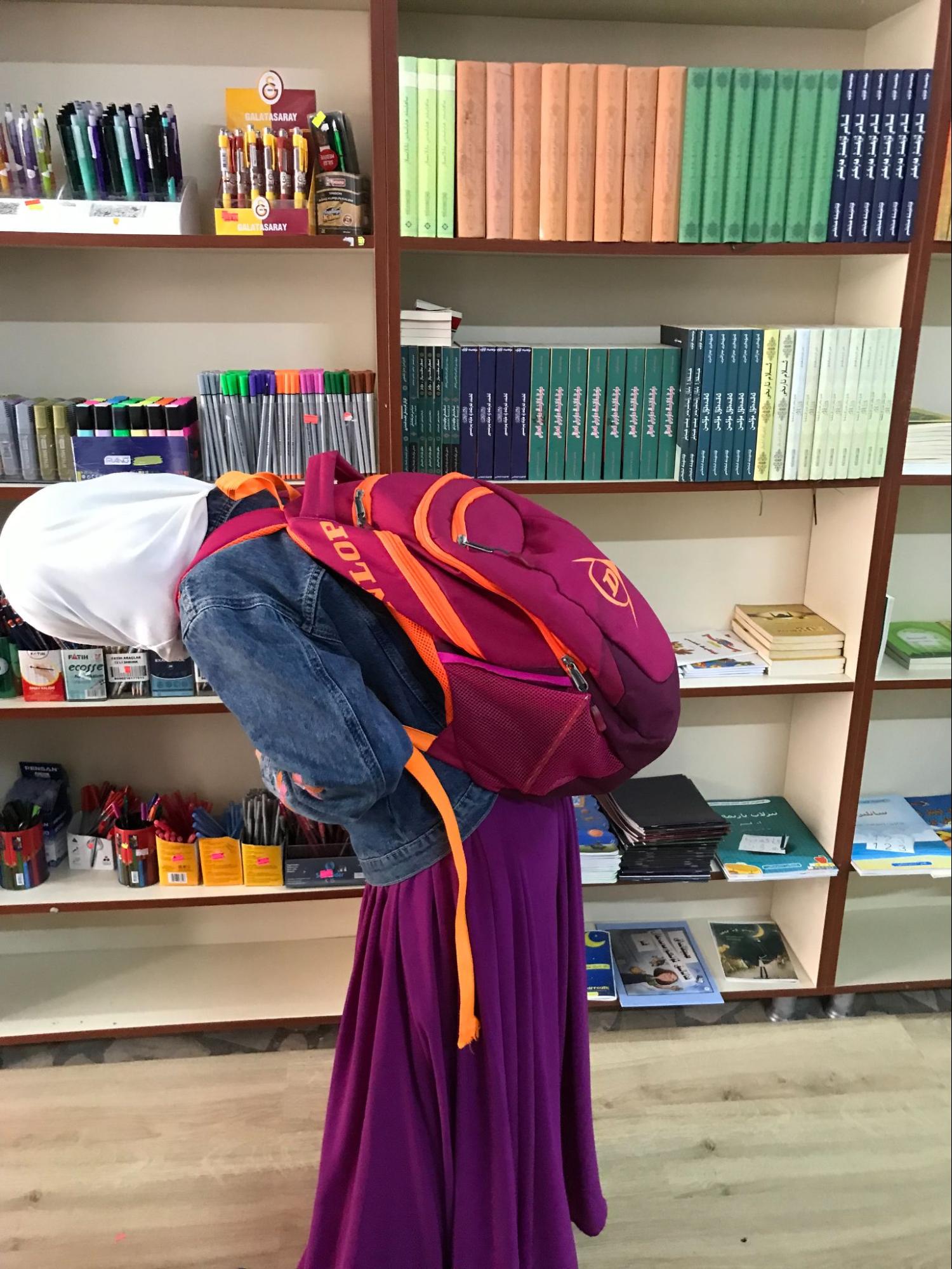

Upon his release in 2018, Turkistanli started over, opening a new fully fledged bookshop and stationers, selling Uyghur, Turkish, and Arabic books.

On any given day, the Kutadgu Bilig Bookshop — named for an 11th-century book of morals written by a Uyghur prince — is filled with Uyghur high school students studying, mothers photocopying their children’s homework at bargain prices, and a mix of adult Turks and Uyghurs just browsing.

Less than a mile away, in a small alley shop, Turkistanli opened a lending library especially popular with youngsters who gather in large numbers after school to devour the roughly 500 children’s books in the collection.

Turkey’s recent economic woes have many exiled Uyghur adults hustling to make ends meet, causing a drop in visitors to the bookstore and the library.

“But kids come a lot,” Amine told The China Project. “We give them drinks and welcome them to come here and read. It is so important for them to be educated and to read so that they can stand against all the pressures they will face in society.”

Police raid

The police raid in August 2022 shattered the bookstore’s fragile peace.

“They removed thousands of books the first time and we think they have been burned,” Turkistanli said.

When the police came the second time, after dark one night in March 2023, the community was ready. Several hundred supporters, mostly women and children, converged on the bookshop to protest.

As police vehicles arrived, sirens blaring, officers with riot helmets ran down the stairs into the basement bookshop and began pulling books off the shelves and loading them into sacks.

“One old woman barred the way and shouted out that books were precious for their lives,” Turkistanli said. “She asked them why they were taking away their souls. They were so upset, particularly the women who are concerned about their kids’ education. Some lay in front of the police cars and vans.”

As Istanbul police carted off his dreams, Turkistanli collapsed and was rushed to a nearby hospital to be treated for heart problems that he said started when he was injected with “mystery substances” in the Kirghiz jail.

In the hospital, Turkistanli got word that the police stopped plundering his bookshop when somebody in Ankara from higher up in the government placed a call.

“They told me I could return to the shop and put the books back on the shelves,” he said, laughing. “I made [the police] go back themselves and clear up the mess they had made. We have done nothing to harm anyone in Turkey. Why are they doing this to us? They should be helping us and not kowtowing to China in the destruction of our culture.”

Reprieve

With Ankara’s reprieve, Turkistanli’s case meanders through the Turkish courts. A hearing in June 2023 adjourned until autumn. He hopes the court will decide to allow him to continue printing books not legally available inside or outside China.

“We are talking about books written by our beloved writers that cannot be obtained now anywhere in the world,” Turkistanli said. “Who else can make them available for our people? Surely there can be an exception to allow us to keep printing and distributing them. If our authors, now in prison, could be contacted, they would of course give their permission.”

Aziz Isa Elkun of PEN said Ankara should help Uyghurs in Turkey preserve their endangered culture. Rather than raiding their bookshops, they should provide them with assistance.

“At the very least, they should allow Uyghurs to copy and sell their books,” Elkun said. “Any government committing cultural and physical genocide toward different racial groups should lose jurisdiction over them.”