China’s next overseas military base likely a Sri Lankan port, report says

The People’s Liberation Army Navy’s first overseas military base was built in Djibouti, an East African port already teeming with Chinese commercial interests. Researchers think Beijing could use the same playbook again.

China’s military is most likely to build its second overseas naval base in Sri Lanka, according to a new report that studied where Chinese commercial firms have invested most heavily in establishing harbor and port infrastructure to protect international trade in such things as consumer goods exports and imports of oil, grain, and rare earth metals.

The People’s Liberation Army Navy built its first overseas outpost in Djibouti, East Africa, in 2016, at a cost of $590 million, where up to 2,000 personnel have used the base to stifle piracy of Chinese cargo vessels sailing the waters around the Horn of Africa and the approach to the Suez Canal leading to the Mediterranean and Europe.

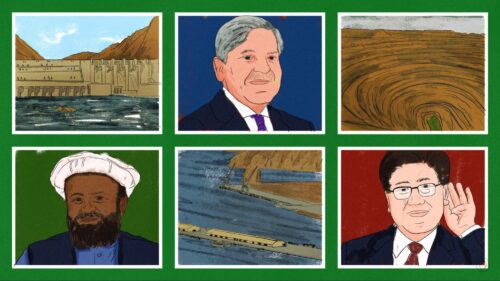

Sri Lanka tops this list of eight international ports where China is most likely to land its next overseas military base in a July 2023 report, titled “Harboring Global Ambitions: China’s Ports Footprint and Implications for Future Overseas Naval Bases,” written by researchers at the AidData lab at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. To come up with the short list, researchers assessed 78 international harbors in 46 countries that are most likely to harbor ships from the PLA Navy’s fleet of approximately 500 vessels, the largest navy in the world.

AidData’s inaugural report of this kind found that Chinese firms spent about $30 billion from 2000 to 2021 to build out the 78 ports assessed. The report assumes that China will locate its next PLA Navy base by leveraging influence built up by previous investments, as it did when the base in Djibouti was built next to the commercial port of Doraleh, which, until 2018, was part owned and operated by China Merchants Holdings, and was a major hub for livestock transshipment.

Ports assessed in the report were ranked based on their strategic location, harbor depth for naval vessels, political stability in the host country, and the host government’s tendency to vote with China in the UN General Assembly.

Hambantota, Sri Lanka

Topping the short list in the AidData report is the port of Hambantota in Sri Lanka in the Indian Ocean. China has invested $2.19 billion in Hambantota, more than in any other port, and the government in Colombo agreed to lease majority ownership of the port to a Chinese firm in 2017. In 2018, China gifted the Sri Lankan navy a frigate and the report notes that Sri Lankan elites and the general public have a favorable opinion of China and the Chinese people.

Western analysts speculate that in addition to Hambantota, the ports at Ream, Cambodia, Gwadar, Pakistan, and Equatorial Guinea’s Bata or Cameroon’s Kribi could host the PLA Navy. The report’s authors said that they hoped to widen the discussion to include a broader range of possible locations better reflecting China’s ambitions for a global navy. The Pacific island Vanuatu, the port of Nacala in Mozambique, in East Africa, and Nouakchott in Mauritania, in West Africa, round out the short list.

“China has this very ambitious foreign policy, and it has this massive navy, which for sure was not built to hang around in Chinese waters,” Alexander Wooley, one of the report’s authors, told The China Project. “There’s a certain logic that these bases have to come, but China has been very restrained so far. The sheer range of options that China has hasn’t been appreciated as much previously.”

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

Equatorial Guinea and Cameroon

The ports of Bata in Equatorial Guinea and Kribi in neighboring Cameroon are only 100 miles from each other, both on the west coast of Central Africa, facing the South Atlantic. The AidData report said China likely would favor Bata, ranking it No. 2 on the short list of ports most likely to host the PLA Navy’s next base, followed by Gwadar, Pakistan, at No. 3. Kribi is ranked No. 4.

Bata or Kribi would position China’s navy to protect increasingly busy sea lanes floating with rising African exports to Asia. Piracy in the nearby Gulf of Guinea provides further justification for locating a PLA Navy base here.

Equatorial Guinea and Cameroon both are ruled by stable families with no looming succession crises on the horizon, providing political predictability that Beijing prefers to some democracies where the welcome mat for China’s military risks being rolled up at the next major election.

China putting a naval base anywhere in Africa is liable to trigger locals’ painful memories of colonialism by European powers, the report’s authors noted. China aims to present itself to countries in the Global South as a non-interventionist power with the developing world’s best interests at heart, a narrative that could lose credence if China builds a second military facility in Africa.

Potential Chinese navy ports in West Africa likely also would face heavy pushback from the United States. When, in 2019, U.S. military intelligence suggested that China was considering a base in Equatorial Guinea, American officials began urging government officials in the African nation to reject any such plans.

Military planners in Washington are most threatened by the idea of China’s navy putting a base in West Africa. The AidData report notes that the distance from Senegal to New York City is a mere 4,000 miles, within the 5,000-mile range of China’s most advanced destroyers, ships equipped with stealth guided missiles.

Gwadar, Pakistan

Pakistan, already the largest buyer of Chinese military exports, is a key player in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. A naval base at Gwadar would cement its strategic alignment with China. China also enjoys strong favorability among Pakistan’s public; China’s popularity rating in the country is 87%, while the U.S.’s rating sits at 27%, the highest differential in the world, the report notes.

Gwadar also may play a key role in supplying China with imports such as food and energy resources. Chinese policymakers and military strategists worry that in the event of a regional conflict, disruptions to supply chains could result in unrest in China. Adversaries such as the United States could choke off strategic shipping lanes such as the Malacca Strait between Singapore and Malaysia, in what Chinese scholars have dubbed the Malacca Dilemma.

Gwadar could prove an end run around Malacca, allowing China to import and export overland via the 1,800-mile China-Pakistan Economic Corridor running from Pakistan’s southwestern coast to northwestern China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

Ream, Cambodia

Satellite imagery, published in July 2023, of a long pier near completion at a naval base in the port of Ream, Cambodia, led observers to note that the facility was too large to justify use by the Cambodian navy alone, and that it resembled a pier in Djibouti, at the PLA Navy base there.

Cambodia’s close relationship with China led observers to speculate that China could use the port for military purposes. Both China and Cambodia have denied that the base will be used by the PLA Navy.

China also enjoys popularity among Cambodian elites thanks to its Belt and Road Initiative investments, and Prime Minister Hun Sen, the head of state since 1998, tends to help align the government with China in UN General Assembly votes.

While China has denied intentions to base any naval assets in Ream, the AidData authors point out that Beijing similarly made repeated denials of any plans for a base in Djibouti, all the way up until the naval facility was announced.

Keep calm

U.S. policymakers reading AidData’s report may feel threatened by a potential projection of power by the Chinese military if it establishes bases abroad, but the report’s authors caution against alarmism.

An American overreaction to the potential for a second Chinese naval base abroad could provide Beijing justification to move ahead with that very expansion, the AidData report said. Fear from Washington also could ratchet up an already tense relationship and raise the risk of conflict.

It is not difficult to understand why China, the world’s largest trading nation, would want to build overseas ports for the PLA Navy. China is a net importer of food and oil, bringing in 67.3% of its crude oil supply in 2019, a level likely to rise, according to one study.

“You typically want to protect your interests, you want to protect sea lines of communication,” Wooley said. “That’s what a navy does. You would expect to need overseas bases at some point, but the sky is not falling if that does happen.”

Competing views

AidData’s report departs from past scholarship on China’s ambitions for overseas naval bases. In 2022, the think tank the RAND Corporation published “China’s Global Basing Ambitions: Defense Implications for the United States,” a report whose authors noted that Hambantota and Gwadar, at the mouth of the Gulf of Oman and called, by some, the crown jewel of Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative, were likely ports for PLA Navy bases. But, RAND argued, China might opt to build bases where Chinese have yet to invest heavily.

The RAND report concluded that Bangladesh and Myanmar also would make prime candidates for a Chinese naval base, despite the fact that ports in those countries have not seen the same levels of investment from China. Instead of using past investment in ports as a criteria in the analysis, RAND looked instead at Chinese investment in host countries as a whole.

While the AidData report’s data-driven approach was useful in highlighting possibilities that may have been overlooked, Harrison Prétat, the associate director at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ (CSIS) Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, told The China Project that political and strategic factors would be the primary drivers of Beijing’s efforts to establish overseas bases.

“I think it’s clear that the scale of Chinese investment is not a direct determinant of whether a given port is likely to be considered for military development or use by China, and that political and strategic factors remain primary,” Prétat said. “The study itself acknowledges that Ream Naval Base in Cambodia, which seems very likely to offer some level of access for China’s navy upon completion of its upgrades, had very little invested in terms of dollar amount.”

For now, China may refrain from building out bases for explicit military use, concluded a 2022 article titled “Pier Competitor: China’s Power Position in Global Ports,” in the journal International Security. The authors noted the challenges and vulnerabilities of building overseas military bases and emphasized China’s capacity to use commercial ports for military logistics and intelligence-gathering.

Getting foreign governments on board with a permanent Chinese military base abroad is also simply a tough sell, said Prétat.

“At the moment, almost no one wants a Chinese naval base on their soil, whether for domestic political concerns or their own strategic hesitations about inviting that level of Chinese presence,” Prétat said. “A deal providing for regular Chinese military access to a commercial port or a country’s own naval facilities is theoretically an easier sell that could accomplish the same goal of allowing more Chinese ships to operate further from China for longer periods.”

Wendy Leutert, one of the authors of the article in International Security and a professor at Indiana University, agreed that China will face challenges in building bases abroad.

“Any moves to develop a large, global base network would invariably face intense international pushback,” Leutert told The China Project. “This makes leveraging commercial port assets for military purposes an attractive alternative in the near term, despite this strategy’s clear limitations in wartime or crisis scenarios.”

A new dataset

To assess the top eight international ports likely to land a new PLA Navy base, AidData drew on the third edition of its Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, set to be released in full this fall.

The first-of-its-kind dataset compiles more than 20,000 projects financed by more than 300 Chinese state-owned enterprises from 2000 to 2023, making it the largest dataset of its kind in the world, the AidData report authors said.

“The dataset provides a holistic picture of where these Chinese-funded ports are located,” Wooley said. “The data has lots of detailed information about the actual financial agreements, the geospatial information, the project narrative, etc.

“We were personally and professionally interested in the topic of potential [PLA Navy] bases, as each new rumor in the media seems to galvanize national security types,” he added. “So we decided to see if our data could help us answer the question, or point us in the right direction.”