The next world war will be economic — even if the weapons don’t work

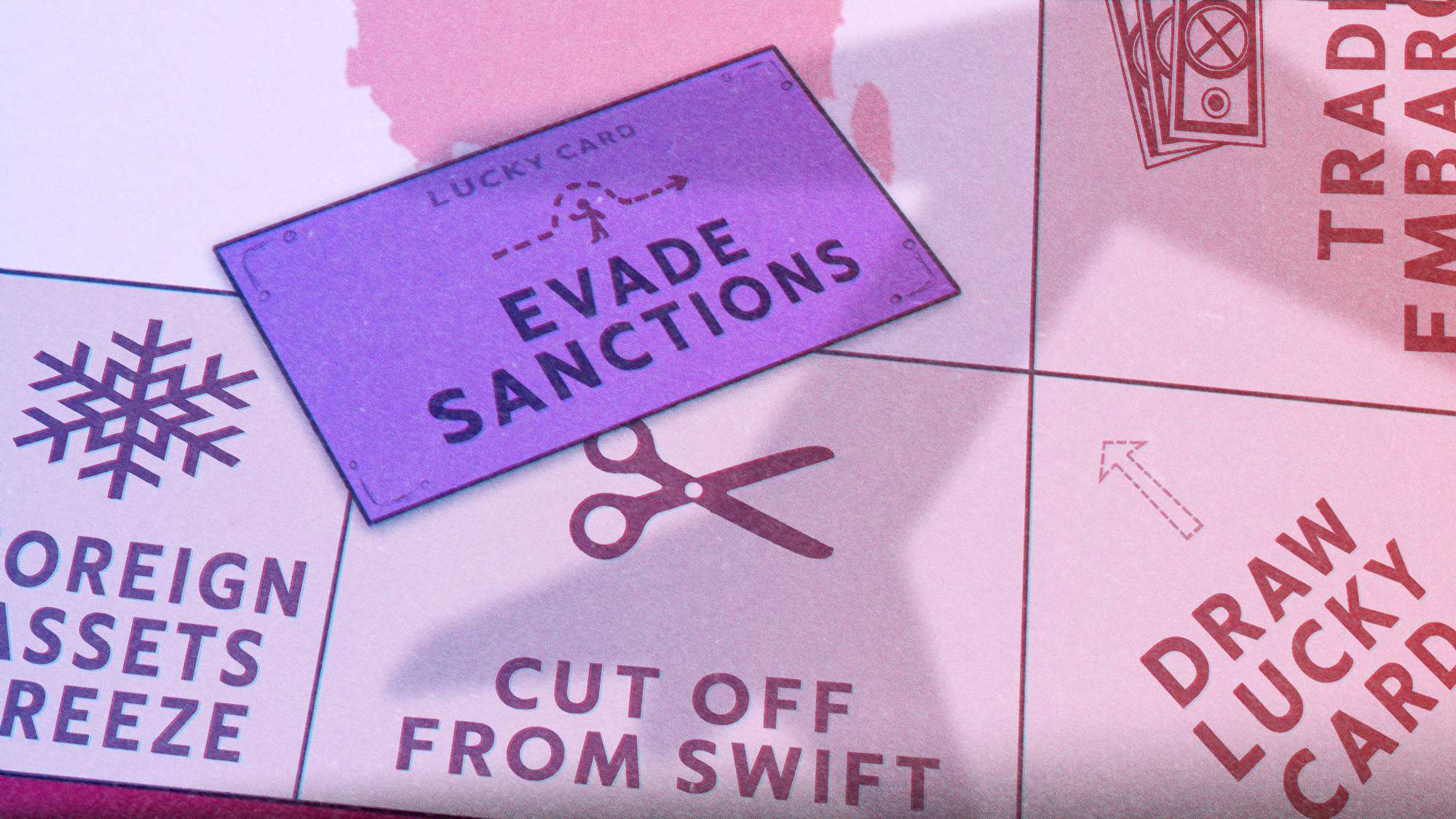

Time and again, history has shown that economic statecraft — sanctions — are ineffective. Yet the future of modern warfare will be fought with spreadsheets, tariffs, and trade restrictions. Both the U.S. and China are gearing up, possibly to everyone's detriment.

Although no films have been made, nor monuments erected, to celebrate sanctions, economic statecraft — the most polite way to describe financial warfare against another nation, group, or individual — has been as much a part of American foreign policy as muddy-boots counterinsurgency, death from the belly of a B-52, or drone strikes.

Even if our imaginations can dredge up more visceral fantasies of conventional warfare, we might, from a lifetime of newspaper headlines and news reports, have a sense of what sanctions are about: trade embargoes, export and import restrictions or bans, disconnecting individuals and banks from the international monetary system, freezing of foreign bank accounts…

Some of these programs are minimalist: A Dongbei good ol’ boy running a casino in Laos gets caught up in some animal parts smuggling and finds he can’t bank with Americans anymore, for instance. Some never get off the ground: “Crippling Unhinged Russian Belligerence and Chinese Involvement in Putin’s Schemes Act of 2022” is a recent example — a few days’ coverage, then we hear nothing from them again. And some seem permanent: Sanctions in North Korea have outlived their architects, Iran had its original sanctions lifted by the Algiers Accord but every occupant of the White House since Jimmy Carter has slapped on new ones, Cuba…well, let’s just say three generations of Canadian tobacconists have made a living from selling cigars to American cross-border shoppers.

Sanctions were a tool of interwar liberal internationalism, conceived to help the League of Nations to restrict the rise of fascism without firing a shot. They were revived for the economic warfare programs of the Cold War. They were resuscitated again in the “sanctions decade” of the 1990s. It is likely that the next world war will be fought in the global financial system.

A new way of looking at warfare

If a deeper conflict is sparked between China and the United States over a Taiwan emergency, there are unlikely to be any set-piece naval battles on the Pacific. There will be no amphibious assaults. These are fantasies that reach back to Midway and Guadalcanal, but are no longer relevant. Given both countries’ shortages of young males, surplus of high-tech equipment, and investment in softer weapons, economic warfare is the future.

A 2016 Rand report for the United States Army, written with China in mind, promises that “well-orchestrated economic sanctions can punish, weaken, and coerce adversaries,” while a shooting war will be plagued by “mounting costs, risks, and public misgivings.” This came out ahead of a new round of sanctions and the beginning of a trade war. As Rand strategists were writing, their Chinese peers were writing reports within their own think tanks, proposing measures to knock down anything their American counterparts proposed. Planners in China have been working to sanctions-proof their economy. Both sides know what the future holds.

There is limited clarity on the efficacy of sanctions and, even among well-informed non-specialist observers, no clear idea on how they should be conducted to maximize efficacy.

As the U.S. seems intent on pivoting again to Asia and the leadership of the Communist Party continues to signal that Taiwan can be taken, the war games have started up again. NBC’s Meet the Press collaborated with the Center for a New American Security’s Gaming Lab for a prime-time experiment, with a blue team stocked by hawkish think tankers and Congress people, and a red team of Rand and Institute for National Strategic Studies German Marshall Fund Alliance for Securing Democracy China experts.

These war games are disconnected from reality. NBC kicks theirs off, for example, with a nuclear blast off of San Francisco. Even when the absurdity is toned down, however, they only take into account conventional exchanges. That makes them next to useless in gaming out the coming conflict. Unless economists, commodity price analysts, logistics experts, and bankers can be spread out among the red and blue teams in a war game, there’s not much sense in even bothering to push the planes and aircraft around the board.

The hesitancy to replace hard with soft warfare in simulations is down to many factors. It reflects ongoing jockeying between elements of the American bureaucracy and the military and political class over how best to handle a hypothetical Fourth Taiwan Strait Crisis.

They also reflect an overwhelming confidence in the economic weapon. We know planes can be shot down and we can imagine a city falling, but it is harder to conceive of success or failure with sanctions. There is limited clarity on the efficacy of sanctions and, even among well-informed non-specialist observers, no clear idea on how they should be conducted to maximize efficacy. When sanctions receive a public airing, the counterclaim is often made by activists who fear they can be too potent, as was the case with opposition to the siege of the Iraqi economy between 1990 and 2003, which very quickly began to contribute to excess mortality among young people. The truth is much more complicated: Sanctions can create critical blowback against the sender nation, paradoxically strengthen the target nation, produce tertiary effects that cascade through the global economy, or simply have no effect at all.

A brief history of sanctions against China

Even when China had limited capacity to retaliate directly, and its role in the global economy was more limited, sanctions against China have routinely failed to accomplish anything, or have had the opposite effect.

From the founding of the People’s Republic of China in October 1949, the United States put economic pressure on it. At this point, China seemed vulnerable. The country was an economic disaster. The countryside was hungry, inflation in the cities was out of control. As the leadership of the Communist Party set about on its campaigns of industrialization and economic stabilization, its overtures to the U.S. were, if not completely rebuffed, then not taken seriously.

There was, within the American political establishment, a two-line struggle over “Red China.” On one side, headed by Secretary of State Dean Acheson, were those promoting compromise and trade with China to head off its absorption into the socialist bloc; opposing them were powerful elements within the Central Intelligence Agency and State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research that held to the line promoted by the China Lobby — the boosters of Chiang Kai-shek (蒋介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) in Washington — that economic hardship would eventually weaken Red China enough for it to be re-liberated by the Kuomintang.

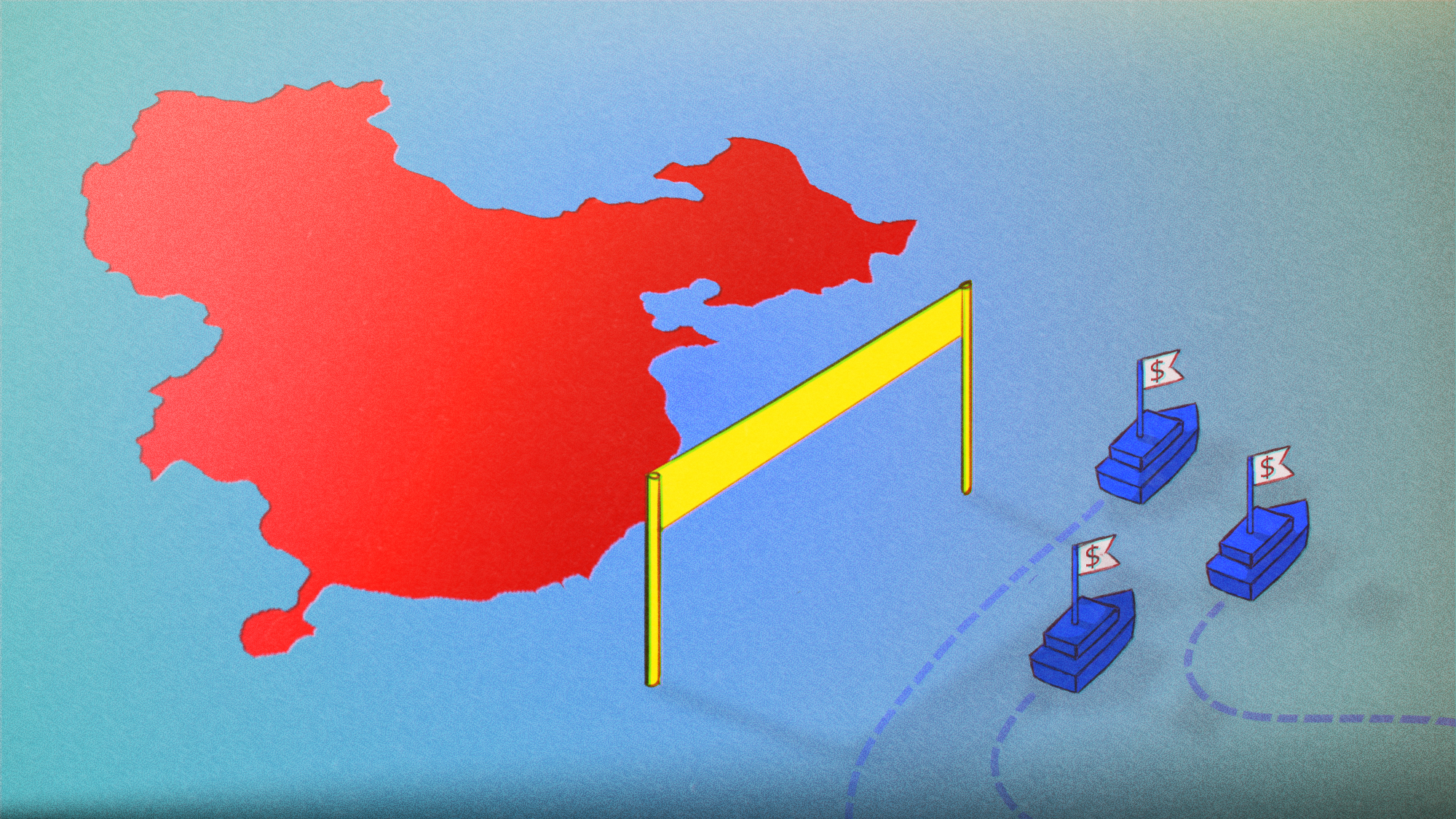

While diplomacy and limited trade continued between China and the U.S. into 1950, any possibility for compromise was foreclosed by the crossing of the 38th parallel by Kim Il-sung’s troops in June 1950, the outbreak of a war, and China’s entry into the conflict. While the fighting continued on the Korean peninsula, economic warfare proceeded apace. A trade embargo was slapped on the P.R.C., which held in place until the joint Sino-American Shanghai Communiqué in 1972.

The results of this severing were negligible. Rather than helping to pull China into an alliance with the U.S., sanctions pushed its leadership into an uncomfortable and short-lived dalliance with the Soviet Union. Without the United States and then the Soviet Union as a destination for goods, or a source of aid or industrial inputs, the Chinese government simply expanded trade with North Korea, Vietnam, and Mongolia, as well as, eventually, France, West Germany, and Italy. The scholar Xin-zhu Chen sums it up this way: When Japan began trading with China in 1960…

…the embargo became all but a joke. China could obtain from West Europe and Japan virtually everything that the United States wanted to deny it. Thus, the trade embargo, which was originally designed to contain China, had turned into an invisible fence to isolate the United States from the China market, much to the chagrin of American merchants. It would not be until the 1980s the United States regained a meaningful share of the China market long dominated by Western Europe and Japan.

If economic growth was compromised, it was by internal factors, rather than sanctions. The trade embargo against the P.R.C. did nothing to accomplish stated and unstated foreign policy objectives. In fact, it was the lifting of sanctions in 1972 that made possible a fruitful commercial, diplomatic, and military alliance that arguably helped defeat global communism.

In 1990, another round of sanctions following the crackdown on Tiananmen Square protesters had similarly minimal effects. Aerospace and military exports were halted, foreign aid was restricted to a handful of projects, and it became easier to freeze the assets of anyone connected to the PLA or Chinese government. These led into more directed sanctions against the military-industrial complex, intended to force China to abide by nonproliferation agreements and end sales of nuclear and ballistic missile technology to Pakistan and Saudi Arabia.

It’s hard to conclude that China improved its human rights record over the next decade, and it’s almost certain that it continued to sell nuclear and ballistic equipment to enemies of the U.S.

Piecemeal sanctions and — still falling under the category of economic statecraft — trade war measures that have been levied over the past five years have impacted specific firms, like Huawei, but failed to rebalance the economic relationship between the two countries or achieve stated goals, like halting human rights abuses against ethnic minorities in Xinjiang.

Sanctions against China have failed.

“This is not the world that we actually inhabit”

Even under extreme pressure, China’s leadership was able to find solutions. When hardship was inflicted, it was weathered. This is not unexpected: Economic warfare has failed not only with China, but with nearly every other target.

As a tool of interwar liberal internationalism, sanctions could not help the League of Nations restrict the rise of fascism. When it was revived for the economic warfare programs of the Cold War, it did not put a dent in the Soviet Union or its allies. Resuscitated in the “sanctions decade” of the 1990s, it proved ineffective for correcting human rights abuses or solving nuclear nonproliferation.

In Richard Pape’s controversial paper “Why Sanctions Do Not Work,” Pape estimates economic coercion of various forms to have worked in only 5% of cases surveyed. Successes were mainly trivial, at least viewed from a global historical perspective, including a release of prisoners from El Salvador, and Prime Minister Joe Clark backing down from a campaign pledge to move the Canadian embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. The record since Pape’s 1997 survey is not much more impressive. North Korea, for example, now effectively amputated from the legitimate global economy, has managed to maintain political stability and develop ballistic missile and nuclear weapons programs. Where sanctions in Iraq failed, the United States military succeeded.

There seems to be no correct thinking within the State Department or its private advisors. Judging by its continued use by the United States against a wide range of targets, confidence in economic coercion as a weapon has never been higher.

Larger economies can usually maneuver out of any pressure, and even more vulnerable targets do not fall easily. “Sanctions would no doubt work better in a world of perfectly rational, consistently self-interested subjects,” Nicholas Mulder writes in the conclusion to his survey of the economic weapon, “but this is not the world that we actually inhabit.” Drawing a parallel with strategic bombing campaigns, Tanner Greer asserts a “flawed psychology” is at work here. History shows that the response to soft or hard coercion is unlikely to be “disintegration, disorder, or abject terror,” but rather “feats of sacrifice, a spirit of stoicism, and the strong sense of solidarity that comes only through shared suffering.”

The correctness of the skeptics’ position is immaterial, since there seems to be no correct thinking within the State Department or its private advisors. Judging by its continued use by the United States against a wide range of targets, confidence in economic coercion as a weapon has never been higher.

In his The Art of Sanctions: A View from the Field, which has become a textbook for economic statecraft, Richard Nephew, former State Department cadre and now preeminent American sanctions theorist, enthusiastically concedes that pessimists like Pape are correct, but uses that admission to argue for redoubling efforts to design effective sanctions. Nephew conceives of a new framework for coercion, centered on the idea of pain. In his vision, economic statecraft is about the “application of pain against another state via sanctions to achieve a defined objective,” and combating the ability of “sanctions targets to resist, tolerate, or overcome this pain and pursue their own agendas.” Pain is inflicted through “inflection points,” the economic equivalent of heel hooks, capable of tearing ligaments and twisting nerves, while leaving the rest of the body unmarked.

And so, if we, like Nephew, admit, too, that the skeptics are probably right, we must begin to push the scenario to extremes. Carried out at the present intensity, with the present targets, and the present level of international coordination, they would fail — but is there a level of intensity that would inflict enough pain? Could it be done without imperiling the American economic system?

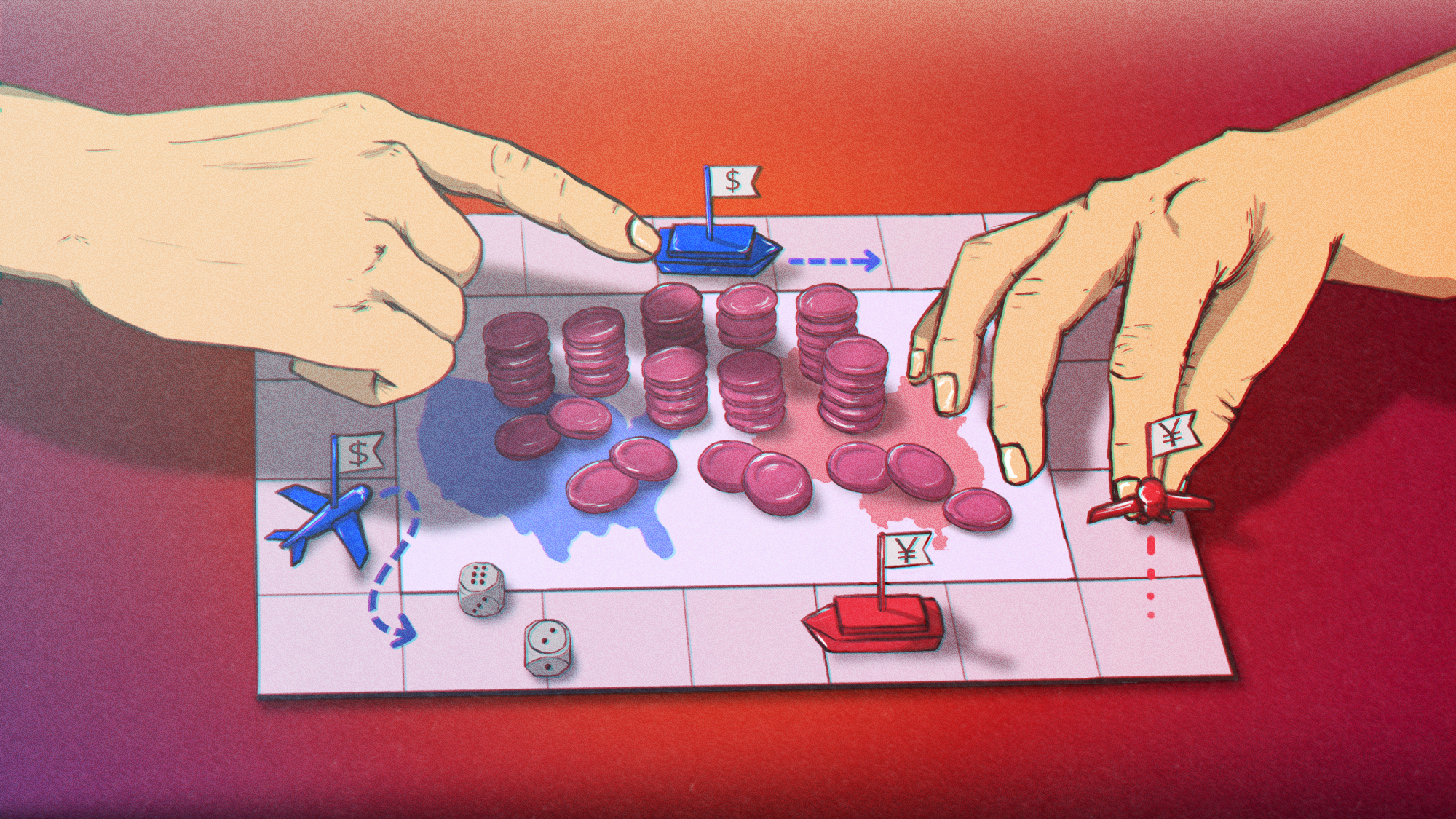

Economic war games

Economic statecraft can be a tool of the military-first fire-breathers, the liberal internationalists, or the doves. It can be a weapon of war or an alternative to fighting. Everyone keeps sanctions tucked in their back pocket without bothering to figure out if they would accomplish anything.

Gaming out sanctions is to interrogate their effectiveness. It doesn’t matter if they are moral or ethical — how would they work?

In gaming out full-scale sanctions against China in the event of a Taiwan emergency, there is little value in imagining only the gradual intensification of export restrictions or a longer list of names being added to travel bans. To gauge efficacy means pushing economic warfare to the limit. This is a lesson to be learned from conventional war games, which put relevant strategic thinking and real-world troop or aircraft numbers to their fullest test by pushing scenarios to their maximum volume and intensity. Those gaming out economic warfare should be willing to consider the equivalent of a nuclear detonation in San Francisco.

How does one make sanctions really burn?

To answer this question, we necessarily move into the realm of fantasy, or what could more grandly be called scenarios for futurology. These scenarios are not intended to be a recipe for a sanctions program, but perhaps an illustration of the lengths to which sender nations would have to go to create the conditions that would dissuade China mid-thrust from taking Taiwan.

The move is not enough to freeze the assets and restrict the travel of members of the leadership, as has been suggested. This would target the billions of dollars stored in overseas accounts by Communist Party leaders and their family members, but the scope would need to be expanded further to encompass lesser bureaucrats, regional Party functionaries, and the management of state-owned enterprises. However, in the first case, the leadership, even if they stand to forfeit personal fortunes, would gain little from betraying the Party; in the second case, the amount of pressure that could be exerted by an internal revolt is minimal, and, for everyone losing their shirts under sanctions, there would be a replacement to be drawn from the new elite that would make a fortune cornering the market on import substitutions.

The scope needs to be further expanded: A vast swathe of the wealthy need to find their access to the global financial system restricted and piles of money frozen. This is not strictly an economic measure: It’s one already exercised in a limited way, through restrictions on American visas for Party members, and the curtailing of travel documents for the business and political elite.

Is that enough? Probably not. Even if it succeeded in sparking a rapid exodus of some portion of the elite, this reality has been priced into strategy already — by the wealthy themselves, who have prepared their exit strategies, and by the Party, which has been careful to ensure that it doesn’t lose anybody it can’t afford to lose.

At a certain point, the scenario has to be expanded to include even more outlandish schemes, like running blockades on foreign ports and interdicting freighters in the South China Sea, or pushing with threats of military action in collaboration with unaligned states. This is pushing the scenario to unbelievable extremes, with predictions of runaway inflation or food prices skyrocketing; for any of this to work would mean buying into the “flawed psychology” of sanctions, as well as discounting the pressure that would be faced by G7 governments.

In the end, in gaming out full-scale sanctions, the same conclusions are reached that conventional war games run up against: a hypothetical Pyrrhic victory might entail detonating the planet.

If collapse of the global economy is not an option, then the game ends at a stalemate. The blue team and the red team end the simulation beaten and bloodied but without having achieved much of anything.

The unpleasant business of war

The prospective economic war between the United States and China is unlikely to be one-sided, but rather an exchange between two near-peers. China has developed an arsenal of defensive economic weapons, including the 2020 Unreliable Entity List, meant to bookmark foreign firms that cooperate with sanctions against the country, and the 2021 Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law, which provides a legal framework to strike against them. Deep within Beijing think tanks, strategists are no doubt coming up with a further list of formal and informal options to retaliate non-militarily against the American economy (Nephew himself has done this, too, in a speculative 2019 report on how China could fight back against economic coercion).

A sprawling Rhodium Group report, prepared with the Atlantic Council from June of this year, is one place to begin imagining sanctions at a scale large enough that they can’t be ignored.

It takes as a requisite cooperation across the G7. This is despite the fact that coordination would be supremely difficult to manage, especially as they predict “massive global costs” and the holdup of trillions in trade.

This is confirmation: unless pushed to extremes, the game doesn’t make sense.

The G7’s suite of economic measures to address a Taiwan emergency could include sanctions against China’s largest banks and the Ministry of Finance, including denying access to SWIFT and other financial transaction processing systems. If Chinese banks were also cut off from the U.S.-based Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS), which settles around a trillion in payments between financial institutions every day, the effects would be devastating. Especially if carried out within the near-term, before China has fully brought online its own alternative systems for cross-border payments, being cut off from SWIFT and CHIPS devastates any enterprise connected to global markets.

There would be “significant dislocations” of the global economy, with supply chains severed overnight.

This is a solution that has a countdown on it, however. Cutting China off from SWIFT and CHIPS would speed a process of de-dollarization that is already underway. Alternative systems for cross-border payments denominated in renminbi or other currencies, underused at the moment, would quickly become feasible.

The question is whether or not the U.S. and its allies could maintain themselves through an economic assault on China. Sanctions and the resulting global fallout would also bite in the U.S., while the impact on G7 countries could be even more serious.

Rhodium suggests sanctions on the “Big Four” — Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, China Construction Bank, Bank of China, and Agricultural Bank of China — but that could be expanded to smaller commercial banks, as well. Depending on the scale and strength of sanctions, as well as the amount of foreign currency reserves frozen (the Chinese hold around $3.3 trillion in foreign currencies), the renminbi would likely depreciate against the dollar, the Rhodium report concludes, making it more expensive to purchase imported economic inputs, and shrinking overnight the export economies of countries that depend on sending industrial and agricultural commodities to China. Volatility across the international monetary system will ripple out from Chinese banks.

After this would come the imposition of sweeping export controls. These would include a wide range of strategic commodities and technologies. Imagining a coordinated effort across the G7, which would include controls on fertilizer and agricultural exports, a rapid and thorough rebalancing of the Chinese economy and domestic supply chains would be required. Cutting off the entry of a wide range of imports would be a powerful follow-up.

These two sets of measures would inflict a measure of pain. Jobs would be lost or employees idled as export markets contracted and inputs began to struggle to get through. Food prices could rise dramatically as agricultural imports begin to grow scarce or much more expensive. But this assault would be devastating only in the medium-term. Chinese planners have sanctions-proofed the country’s economy to some degree, built up strategic reserves of key industrial and agricultural commodities, limited accumulation of foreign reserves, attempted with the dual circulation strategy to provide shelter from global markets, and developed alternative financial cross-border payments systems. A more complete system for macroeconomic control could be crucial to allowing China to maneuver out of any crises.

Cultural, ideological, and political factors, like popular nationalism, living memory of more extreme deprivation, and state control of information, would work in the country’s favor, even though this is difficult to quantify. We must also imagine in this scenario that there is a blockade underway, a counterinsurgency being fought, or some process to fold Taiwan back into the People’s Republic. What we assume would be a popular war would likely improve popular psychological resilience.

The planet would rebalance itself around its two largest economies. In their assessment for Center for Strategic and International Studies, Jude Blanchette and Hal Brands describe a bifurcation of the global economy with “two self-contained monetary and financial systems might emerge,” one denominated in the dollar and the other in the renminbi.

An argument for engagement

Could the U.S. and its allies could maintain themselves through the assault? Sanctions and the resulting global fallout would bite in the U.S., where exports to China now total $153.8 billion and imports total $536.8 billion. The impact on G7 countries, like Canada in particular, where China trade hit a new record in 2022, could be more serious. Rhodium estimates over a million jobs in G7 countries tied only to exports of items that would be caught up in limited sanctions on chemicals, metals, electronics, and transportation equipment. Rebalancing or even a more complete bifurcation could not erase all links above — or underground — between the two spheres. The pressure would be immense on the G7, which, despite recent comments from Secretary of State Anthony Blinken on its unity, has not historically been as enthusiastic about defending Taiwan. Once allies began peeling off, as with Western Europe and Japan in the 1960s (or the European Union with Iran trade at present), the siege would fail.

What has to be considered, as well, is that China could, rather than only absorbing pain and waiting for the global economic fallout to break the resolve of the G7, begin to launch its own counterattack. The Unreliable Entity List and the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law would allow China to slap their own sanctions on states and firms that comply with a sanctions program. Even if sanctions are eventually lifted, an ongoing freeze-out of Western business in China and allied economies would mean a significant counterpunch landing. If there is a rebalancing of the global economy, it could see China attracting traditional partners, like Russia and Southeast and Central Asian countries, but also larger economies that are currently not fully aligned with any bloc, like Brazil, Turkey, and Indonesia, through which it could launch another counterattack, slapping sanctions on states in or working in concert with the G7.

These scenarios have likely already occurred to planners. And yet, the United States will continue to pursue sanctions. This is occasionally less about economic coercion of China than it is about accruing benefits to the domestic private sector, or sending a political message to supporters or rivals at home and abroad. China will continue to sanctions-proof its economy, which is also ultimately about building up segments of the private sector or safeguarding its investments — and sending political messages.

The people of both countries, whatever satisfaction they might take from actual or symbolic participation in or resistance to economic warfare, are likely to be dissatisfied with whatever outcomes they are told they have received.

If there is no hopeful denouement to be written from the results of conventional or economic war gaming, nor in the status quo, simulations or futurological scenarios should, rather than being justification for deadlier and dearer tools, bolster arguments for diplomacy and engagement. Whether because we can be sure it won’t work, or on moral and ethical grounds, hard or soft coercion cannot be part of that engagement, which must break with the status quo and take on radically different forms.