Beijing keeps exiled Uyghurs in the dark about relatives in China

The Chinese Communist Party is breaking international laws and ignoring treaties as it continues systematically breaking apart Turkic Muslim families.

Dilnaz Kerim, a Uyghur math student at Queen Mary University in London, has lived with her immediate family in the U.K. for eight years. Recently, the Chinese embassy there told her that, according to its records, an uncle, an aunt, and their families back in China “did not exist.”

These members of China’s largest Turkic Muslim minority are but a few of the 30 of Kerim’s relatives on her father’s side who have disappeared into the black hole of internment centers and prisons that the Communist Party set up in northwestern China starting in 2016 to “cure the mental illness” of Islam.

Refusing to be pinned down about the fate of tens of thousands of Uyghurs disappeared in China’s “War on Terror,” Chinese officials dodge Uyghur questions about relatives by asserting that everyone who was detained in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region has “graduated” from what Beijing called “reeducation camps,” a report by The Rights Practice, a London-based nonprofit, showed in July.

Kerim told The China Project that her father fled Xinjiang in 1991, shortly after Uyghurs took to the streets of Baren township, on the Western edge of the Taklamakan Desert, to protest Chinese authorities’ forced abortion of Uyghur pregnancies. The ensuing clash between Chinese forces and Uyghur militants grew violent and accounts of fatalities vary widely.

Kerim said her father was falsely implicated in the violence and spent six months in detention. When his health failed he was released and fled across the nearby border to Kyrgyzstan, never to return to China. Kerim and her father believe that because of his brief detention 32 years ago, his extended family has been monitored closely by Chinese authorities ever since.

Kerim said that one of her uncles and two of her male cousins were sentenced to lengthy jail terms for “national hatred.” Others in her family, Chinese authorities told her, are “living life normally, mixing with everyone, and able to come and go at will.”

Though Kerim said she doubts Chinese diplomats’ words, she has no way to know what’s happening in her homeland — communications there are controlled by the Party and Uyghurs who have fled China report that they often chose silence inside Xinjiang for fear of official reprisals against friends and family.

“We have tried unsuccessfully to find out where our relatives are,” Kerim said. “We haven’t been able to speak to any of them since 2016 and any information we get is through friends of friends and often delayed for months. If the embassy knows they are living ‘happy lives,’ why can’t they tell us where they are and let us speak to them?”

Kerim says her father, Kerim Zair, tries to keep his sadness to himself but lies awake at night, obsessed with the fate of the family he left behind.

“We hear so many terrible stories from camp survivors about what goes on in the camps and prisons,” Kerim said. “We imagine all sorts of things happening to them. We know they are always on his mind.”

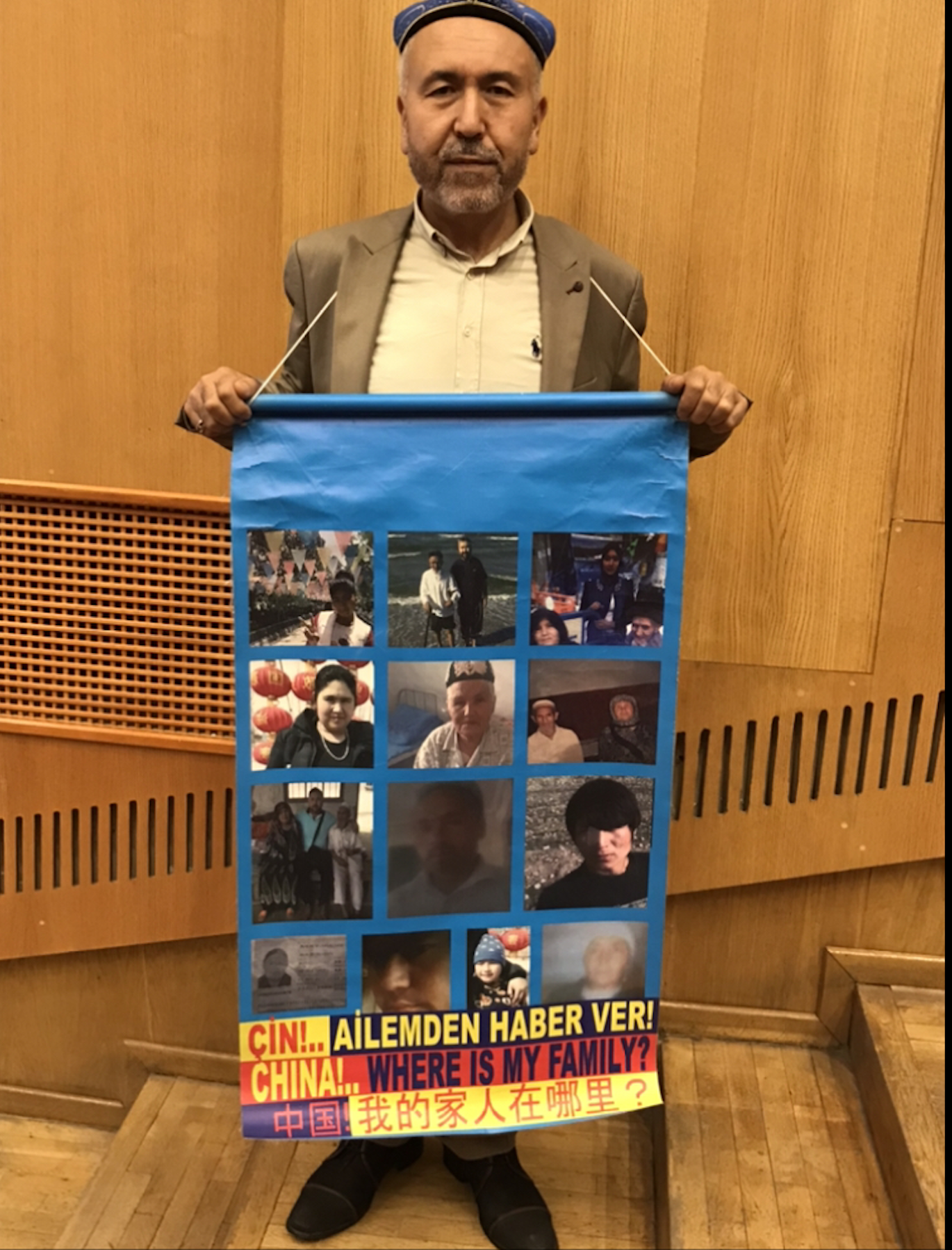

Kerim and Zair are not alone. Their story is not unique. It is repeated throughout the Uyghur diaspora from Tokyo to Istanbul to Washington, D.C., where Uyghur husbands and wives, parents and children, friends and families — all living in exile — await news from Xinjiang.

Numbers matter

“Disappeared by the State: Tracing Uyghur Relatives in China,” the July report, which The Rights Practice timed to herald the United Nations’ International Day of the Disappeared on August 30, claims Beijing deliberately withholds news of Uyghurs interned from 2016 to 2017 in Xinjiang, when more than a million Uyghurs were rounded up and detained illegally.

The human rights lawyers behind the report urge international agencies to press China for information about the whereabouts of family members of thousands of expatriate Uyghurs living around the world and demand closure of the reeducation camps, the end of arbitrary detention of Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims in China, and engagement with international bodies over human rights abuses in the Uyghur region.

The report demands that the International Committee of the Red Cross step up and help find those who disappeared.

Records of some Uyghurs who have not disappeared altogether have turned up in factories around China under conditions of forced labor. Others’ records have appeared in court documents detailing sentencing to long prison terms.

Uyghur exiles seeking answers by asking Chinese authorities to trace family members inside Xinjiang are met with “silence, obfuscation, and threats,” creating an “intolerable situation” for those who wait, the report said.

Beijing’s unwillingness to provide Uyghur families with information about detained relatives has “brought misery to thousands,” lawyer Nicola Macbean, The Rights Practice executive director and author of the report, told The China Project. China’s actions, she said, contravene international law, amount to “enforced disappearances,” and “should be called out by other governments.”

A raft of United Nations laws have laid down standard minimum rules for the treatment of prisoners that involve allowing them close contact with their families and the outside world. They should have access to lawyers and be able to review their sentences regularly. The Rights Practice said all these laws have been violated by the Chinese government in its treatment of Uyghur detainees.

The reeducation camps, known officially as Vocational and Educational Training Centers, or VETCs, have no basis in Chinese law and, Macbean said, “resemble the much criticized and now-abolished system of reeducation through labor.”

The system of camps was rolled out illegally in 2016 by Chén Quánguó 陈全国, then Party Secretary of Xinjiang, with no approval at the national level, the report said. In 2018, China revised its Counter-Terrorism Law to cover, retroactively, the establishment of VETCs. The Rights Practice report shows that the VETCs’ existence still flouted the law’s criteria. The report found that few detained Uyghurs had access, as guaranteed by China’s law, to legal assistance, a fair trial, and an appeal. Uyghur families were rarely notified of legal proceedings in writing and often were unable to visit detained relatives or pass their relatives’ medical records to their captors.

Tens of thousands of cases of Uyghurs detained are detailed in data collected by The Uyghur Transitional Justice Database, the Xinjiang Victims Database, and Uyghur Hjelp, all nonprofit organizations run by Uyghurs in exile trying to locate the disappeared.

Further evidence of Uyghur interments in Xinjiang between 2017 and 2018 was established by the leak of official internal speeches, spreadsheets, and documents now known as The Xinjiang Police Files. These records of 23,000 Uyghurs detained in southern Xinjiang contradicted Beijing’s claims that it was impossible to provide statistics on the numbers of persons detained in VETCs.

“Given the comprehensive records held by the Chinese authorities, it is entirely reasonable to expect that the government can provide fairly accurate information on the total number of detainees on a particular date,” the report said.

Fear pervades

But precise information is hard to come by given Beijing’s refusal to release data and the fear that stalks former detainees too terrified to announce their release or communicate with the outside world to avoid being returned to a camp.

The Rights Practice report was based on a February 2023 survey of Uyghurs living outside China. Respondents agreed unanimously that none of the channels for receiving information from relatives in China works.

“The lack of information about relatives is painful and heartbreaking,” one respondent said.

China’s laws ensure that authorities keep families informed from the moment of a relative’s arrest through to his sentencing. But, the report said, if a detainee is suspected of, or charged with, “crimes endangering state security or crimes of terrorist activities,” keeping a detainee’s family informed is thrown out the window, especially if authorities deem that “such notification may hinder the investigation.”

During the so-called “New Era” of national rejuvenation that President Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 launched across China in 2017, national security became a priority and Uyghurs the main target. None of the protection for detainees afforded by China’s detention laws applied to Uyghurs, since they were considered an existential threat to the safety of the nation.

In the survey of Uyghurs on which The Rights Practice report is based, 66% of respondents said a member of their family was detained in China. Only 9% of those surveyed received official information from their relative’s place of detention. The vast majority, or 87%, learned of their relative’s detention through friends, family, and neighbors. Only one person surveyed received written notification from Chinese police.

Fog of war

Coded language fogs communication between China and the outside world. Families in Xinjiang know that their calls are monitored and fear sharing the whole picture of their daily lives. The only accurate sources are police, lawyers, and neighborhood cadres. No Chinese law provides the absolute right to information for family members regarding their relatives. Seeking more information can have negative consequences.

“A climate of fear encourages self-censorship,” the report said, noting that relatives of exiled Uyghur activists often are targeted in Xinjiang, leaving many reluctant to come forward.

China’s disregard for accepted international laws of detention leaves detainees vulnerable to a “serious miscarriage of justice” and a “high risk of torture,” report author Macbean said.

Despite repeated appeals to Beijing from the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to provide information on the whereabouts and circumstances of those forcibly disappeared or missing in Xinjiang, China’s failure to provide information leaves Uyghur families in distress, the report said.

The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has had limited success in locating the whereabouts of small numbers of Uyghurs. The Herculean efforts of pro-bono lawyers and rights campaigners help, but the detainees who are found are but a few drops in an ocean of tens of thousands who have disappeared.

The UN’s Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances also has had limited success in raising awareness of the extent of disappearances of Uyghurs and other Turkic people in Xinjiang.

The Rights Practice report called for complete and accurate information to be given to the families of those detained in Xinjiang and reminded Beijing of its own obligations under international law to respect and protect human rights.

Macbean said she is concerned with Beijing’s lack of transparency and continued secrecy regarding the missing, especially considering the Communist Party’s determination to ward off probes into the situation on the ground, and its dismissal of NGO reports on the disappearances as “false information” or “distorted narratives.”

One untested avenue to finding the Uyghur disappeared lies with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which describes itself as an “impartial, neutral and independent organization” with an exclusively humanitarian mission to “protect the lives and dignity of victims of armed conflict and other situations of violence and to provide them with assistance.”

According to the Rights Practice report, there is no current ICRC program to provide family tracing services for Uyghurs whose relatives have disappeared. Macbean told The China Project that the ICRC was well placed to liaise with Chinese authorities over missing Uyghurs in a non-threatening way.

“We would like to see the ICRC making this part of its mission,” Macbean said. “If the ICRC can work with Russia over locating Ukrainian prisoners of war, it is entirely possible the same can be done with China for the Uyghurs.”

Without Beijing’s cooperation, finding missing Uyghurs could prove near impossible, Macbean said.

“Giving the details of missing Uyghurs could be something Beijing could do easily with no loss of face,” she said. “But there needs to be political will.”

Matthew Morris, the head of communications for the ICRC for the U.K. and Ireland, said that the ICRC was “not able to comment on the questions” that The China Project shared. The head of the ICRC Beijing delegation media department did not reply to The China Project email.

Meanwhile, a spokesperson for the British Red Cross Society said that the organization “endeavors to restore and maintain family links between people affected by armed conflicts (including those in detention), disasters and other emergencies, as well as in the context of migration.”

Maya Wang, the associate Asia director at Human Rights Watch (HRW), an independently funded research and advocacy organization based in New York, told The China Project that she was concerned about Uyghur detentions and disappearances.

HRW’s 2021 report on Xinjiang concluded that violations of human rights against the Uyghurs and Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang constituted “crimes against humanity,” Wang said. HRW’s most recent report, in August 2023, confirmed that atrocities against Uyghurs were ongoing in China.

“We have no power over the Chinese government, but we have also advocated other governments and international bodies like the UN and the Organisation for Islamic Cooperation to push the Chinese government in the right direction,” Wang said, adding that it was vitally important to keep pushing international bodies and Beijing for justice for the Uyghurs.

“It’ll be a multi-year struggle. Justice is a long and winding road. It won’t be achieved in a day, a year, or a vote,” Wang said. “At stake are the rights of millions of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, the rights of all in China, as well as the legitimacy of the international human rights system,” she said.