This Week in China’s History: September 13, 1971

In the early hours of September 13, 1971, a Hawker Siddeley Trident crashed in the grasslands of eastern Mongolia. The plane had taken off hours earlier from coastal Hebei, near the resort town of Beidaihe, amid rumors, confusion, and panic. All aboard perished. Among the victims was Lín Biāo 林彪 — China’s Minister of Defense, head of the People’s Liberation Army, and Máo Zédōng’s 毛泽东 chosen successor.

This much is really all that we can know with certainty, a remarkable statement for an event that was one of the critical turning points of the Cultural Revolution.

The mysterious crash ended one of the most precipitous political falls imaginable. Just months earlier, Lin had been heir to the world’s most populous country. Now, he was dead, and within days he would be denounced as a traitor, accused of organizing a coup d’etat against Mao. What happened in the days and weeks leading up to September 13, and what happened on that night, has been the subject of official pronouncements, extensive speculation, and several books and articles, but it remains difficult to pin down entirely.

This column has returned to the theme of succession several times. From Princess Taiping to the Kangxi Emperor to the Ming’s Great Ritual Controversy to the Empress Dowager Cixi and others, many leaders have foundered on their ability, and judgment, to determine who would come after them. Mao Zedong led the Chinese Communist Party for 50 years, and the People’s Republic of China from the time he founded it, in 1949. At the height of his power, his authority was unquestionable. The symbol of the party and the embodiment of his People’s Republic, he stood above even the state thanks to a powerful cult of personality.

Lin Biao was a principal architect of that cult. As defense minister, he had compiled and distributed the Little Red Book throughout the military — and then much further. Millions of Red Guards waved the book at mass rallies, and rarely was anyone seen in public without a copy. The party had sought to disenfranchise Mao but keep him as a symbol; thanks in part to Lin Biao’s work, the symbol overwhelmed the party it had helped create.

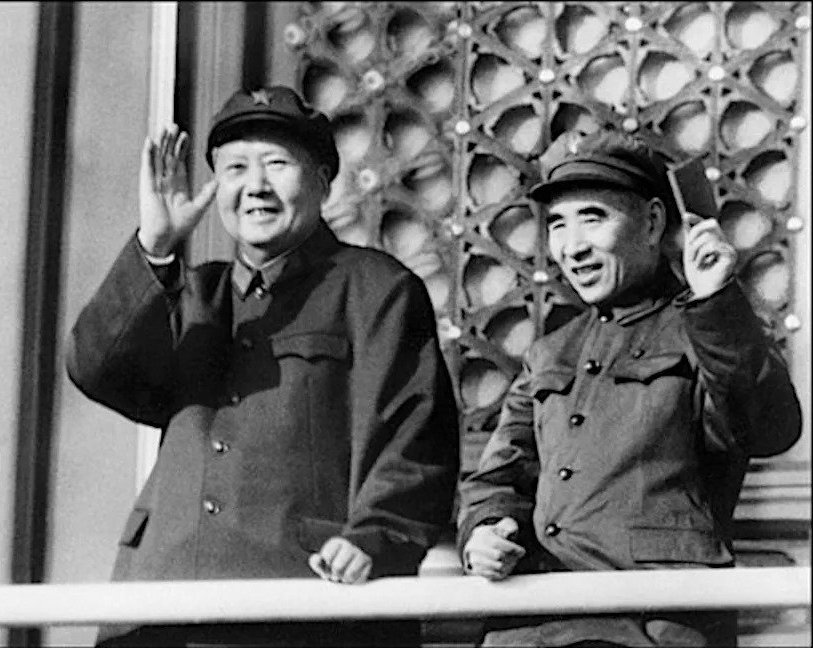

Fueled by the personality cult that Lin helped craft, the Cultural Revolution swept Mao back into power, and Lin replaced Liu Shaoqi in the post of First Vice-chairman of the CCP, making him Mao’s No. 2 and presumptive heir. For the next several years, Lin appeared at Mao’s side and took the lead on many Cultural Revolution initiatives, urging Red Guards to destroy the Four Olds, and was rarely seen without a copy of the Little Red Book in his hand.

But relations between Mao and Lin soon strained. Lin worried about the havoc Mao’s “continuous revolution” had wreaked on the military, and the intervention of political figures, including Jiāng Qīng 江青, on PLA affairs threatened to make matters worse. Lin was formally recognized as Mao’s designated successor in 1969, and from that moment on, Mao felt, Lin’s primary goal was to assume power. By the fall of 1970, the fissure between the two was in the open. By the summer of 1971, Mao was publicly identifying Lin as someone who had committed political errors, and seemed on the verge of removing Lin from his position.

Depressed, isolated, and vulnerable, Lin retreated to his villa at Beidaihe, the Hebei beach resort that had become (and remains) the site of an enigmatic conclave among CCP leaders most summers. He remained there until the night of September 12, when he left by plane and crashed hours later in Mongolia.

The Chinese government’s official view — arrived at after a 1981 trial — is that Lin Biao began plotting in early 1971 against Mao’s rule. The details of the plot — code-named 571 as a homonym for “armed uprising” — are oddly specific, wide-ranging, and often stretch credulity, ranging from blowing up Mao’s private train to ambushing his motorcade to a lone killer with a pistol to an aerial bombardment of Zhongnanhai. Once Mao was dead, Lin and his supporters would establish a capital in Guangzhou, completing the coup from there. The plot remained secret until early September, when Lin Biao learned that Mao intended to purge him. He called on his son, Lín Lìguǒ 林立果, to carry it out: to assassinate Mao Zedong.

In this version of events, Lin Liguo came to Beidaihe to inform his father that he had failed, and the family raced to the airport to escape into exile in the Soviet Union (a reminder of the state of Soviet-Chinese relations at the time). Pursued closely by the authorities, the plane had to depart before it was fully fueled, leading to the crash.

Historians outside China have found this explanation weak sauce, while acknowledging that it’s difficult to make sense of exactly what happened. Lin Biao was an odd man, but he was a noted military strategist who had navigated the most complex of political scenarios. It seems unlikely that he would concoct a half-baked coup plot, and also that he would not have an escape plan ready to go in the event it failed.

Historian Qiu Jin’s 1999 book The Culture of Power pieces together most available sources and modifies the official narrative in ways sure to disappoint screenwriters. Qiu concludes that Lin was not party to any plot. Scholar Tony Saich notes that Qiu’s research reveals a “sickly and passive” Lin Biao who is “a far cry from the active conspirator portrayed in official accounts.” Yang Jisheng’s The World Turned Upside Down is the most recent attempt to understand the events of September 12 to 13, weaving a more compelling narrative than Qiu Jin’s book, but both agree that Lin Biao was not plotting to overthrow Mao.

But while Lin Biao wasn’t plotting, that doesn’t mean there was no plot. Lin’s son, Lin Liguo, also died in the plane crash. Liguo was an officer in the Chinese air force, and he is alleged to have concocted the “571” plan, detailed by an elaborate notebook that was discovered on a table at the air force academy in the aftermath of the incident. Although its discovery feels a little too convenient, there seems little evidence on which to question its authenticity.

Both Qiu and Yang conclude that Lin Liguo acted without his father’s direction — and probably without his knowledge — and put plans in motion to assassinate Mao and establish an alternative government. Those plans failed in the early days of September, and it was a matter of time before the conspirators were found out, so Lin Liguo traveled to Beidhaihe to inform his father. Already distraught by his falling out with Mao, Lin Biao agreed that escape was his only option. The entire family and their closest aides fled, though no one can know truly what their intentions were as they headed toward the Soviet Union.

The most lasting impact of Lin’s death was on Mao’s reputation. Blaming Lin Biao as a turncoat made it easier to purge his followers and eliminate dissent in the leadership, but it destroyed Mao’s aura of invincibility. Mao’s cult of personality depended on his infallibility; any policy failures or bad results were a consequence of incompetence or a lack of faith on the part of subordinates.

Up until the time of his death, Lin was publicly affirmed as Mao’s most trusted confidante. If Lin Biao suddenly turned on Mao, it meant either that Mao had so lost his way that his closest advisers could no longer support him, or that Mao’s judgment was dangerously unreliable. In either case, confidence in the Great Helmsman cracked and never recovered.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.