The present battle to shape China’s future by controlling its past: Q&A with Ian Johnson

Ian Johnson’s journalism gives voice to ordinary Chinese people from all walks of life — the outcasts, the faithful, and, in the case of his latest book, the public intellectuals and storytellers recording the history that Beijing’s official censors are trying to erase.

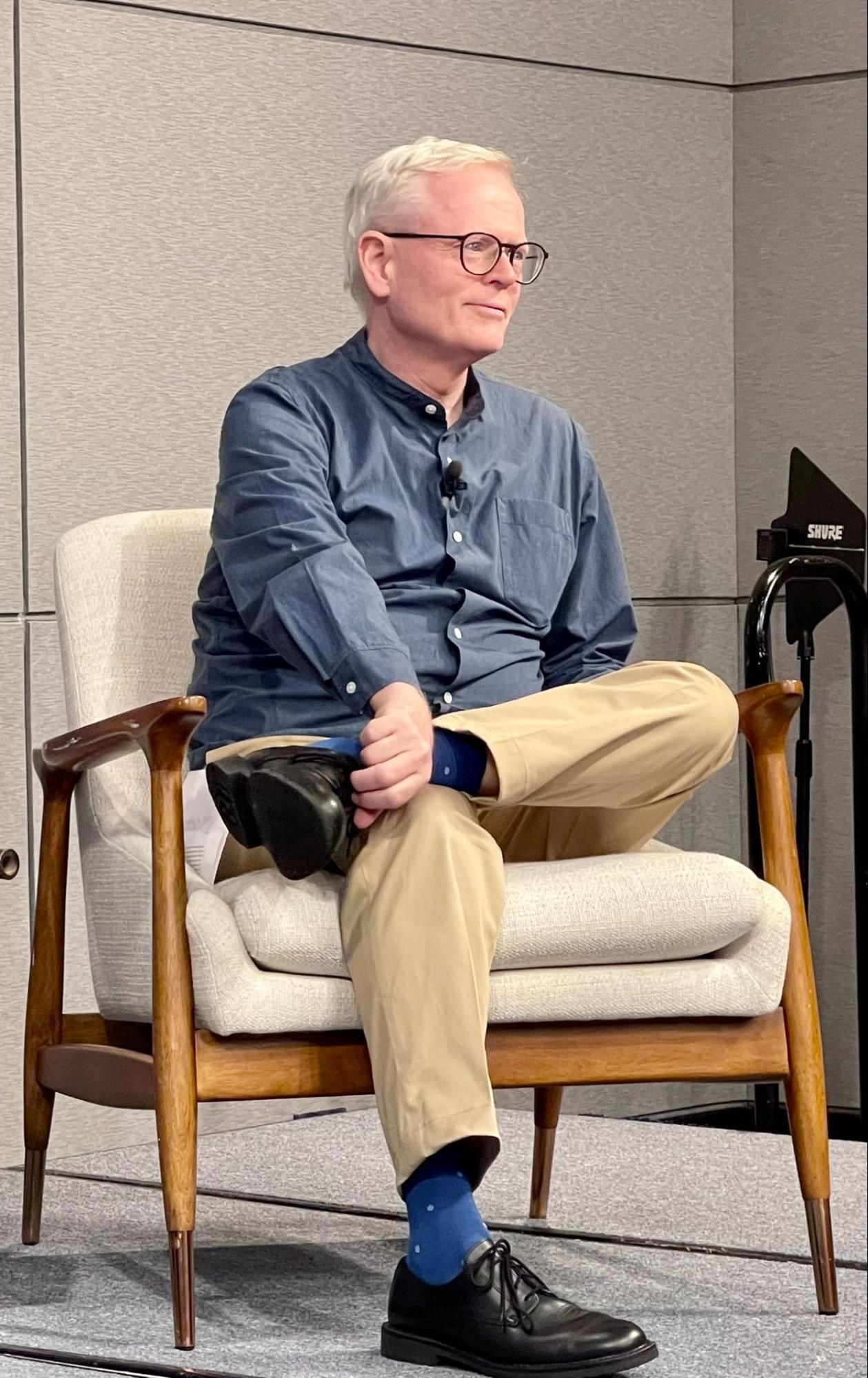

Ian Johnson is a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, researcher, and senior fellow for China studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. His new book, Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and Their Battle for the Future, shows how — despite the best efforts of the surveillance state built by Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 — a nationwide movement has coalesced to challenge the Chinese Communist Party on its most hallowed ground: the control of history.

A Canadian-born American, Johnson lived in China for more than 20 years. He began following the country before first going there as a student in 1984. He has written for Baltimore’s the Sun, the Wall Street Journal, the New York Review of Books, and the New York Times, where he was working when authorities expelled him from China in 2020.

Johnson’s latest book will launch on September 26 in New York City. He recently spoke with Jonathan Landreth. This is an abridged, edited transcript of their conversation.

What’s an underground- or counter-historian?

To understand what a counter-historian is, you first have to understand that the Communist Party legitimizes its right to rule not at the ballot box but on the “fact” that history chose it to run China. This comes up in children’s textbooks, exhibitions, video games, and television shows: The Party has the right to rule China, only the Party can rule, and this has been proven by history. China went through a terrible period, starting in the Opium Wars in the early 19th century. There were well-meaning patriots who tried to stand up for China, but they failed. Only the Communist Party was able to unite China, kick out the foreigners, and modernize the country. There’s an element of truth to all this, but it means that the Party can call on this quasi-spiritual force of history to legitimize its rule.

Counter-historians are people who are trying to come up with alternative forms of understanding China’s past that show that while the Communist Party did achieve certain things, it’s been at a terrible cost and that the Party whitewashes large swaths of history because they would call into question its right to rule. While the Communist Party has achieved certain things, it’s also been responsible for tens of millions of deaths. It would not be an exaggeration to say that over 50 million people died on the Party’s watch — 45 million alone during the Great Famine.

Counter-historians are struggling to tell the complete story of CCP rule going back over 100 years. Counter-historians are not necessarily people who have a Ph.D. in history. I use counter-historian or underground historians as a way to try to translate the Chinese term mín jiān (民间) — intellectuals “of the people,” or grassroots intellectuals. These people are not part of the Party propaganda system. While they may be academics, most of them are not what I would call dissidents in the classic sense. They’re not lonely fighters locked up in a jail cell or under house arrest. Some are, but these are people who often have one foot inside the system — they own property or are teaching at a school — but who probably also have been marginalized in some way because of their pursuit of the truth. They make underground documentary films, they write books, they write magazine articles, and they do guerrilla journalism, a lot of it published in a modern day version of the samizdat movement from the Cold War. These people have suffered a lot under Xi Jinping, but they still exist and their movement has formed over the past 25 years and has not been crushed.

How tough is it for one generation to pass its history on to the next?

The Party has proven that it can silence individuals, but it’s harder to silence an entire class of people permanently, especially when they can avail themselves of simple digital technologies. I don’t mean the Internet and social media, which are more easily controlled, but technologies such as email, PDFs, and digital cameras, which make it so much easier to self-publish. In China, they’ve had a profound impact on how you can share material that is otherwise banned. True, many are under house arrest and have their Internet cut, but I’m talking about tens of thousands of people participating in this movement, not just a few high-profile dissidents.

There’s also much more involvement of overseas people now than there was in the past, people who are very much present in New York City, Taipei, and other major global capitals. In the past, one of the easiest ways to silence a dissident was exile. They became almost a caricature of somebody who couldn’t really interact with their new country and who had zero impact in China. That describes some people, but there are a lot of young people still coming and going and because not all these people are Class A dissidents — we’re talking about students — they’re able to participate, to help.

One of the underground magazines I write about in my book is largely edited in Texas. I don’t know who exactly is involved, but I think they’re Chinese graduate students. They do a lot of logistical work. The writing is still done largely, but not exclusively, inside China. This kind of interaction is possible within digital technologies. I can write something in Beijing and, for safety’s sake — because my computer could be taken — I can email it to some friends elsewhere: Berlin, London, New York, or Dallas. Then they can put it together and then email it back into China. We saw that when White Paper protests effectively used the Twitter handle Lǐ lǎoshī bùshì nǐ lǎoshī (李老师不是你老师; “Teacher Li is not your teacher”) as a way to upload videos, then download them.

You’ve lived in Berlin, home to veteran Chinese exiles Liào Yìwǔ 廖亦武 and Ài Wèiwèi 艾未未, men who continue to spread alternative history from outside China. Are there people still inside China with their level of commitment to the truth?

Just as there is the older generation of famous dissidents, who maybe were involved in Tiān’ānmén (天安门), there’s a younger generation of people who are active, who are not so impressed by those elders. The #MeToo Movement hit that generation. The younger people are not necessarily looking to those people as their intermediaries to China. They may respect what they’ve done. They may like their works, but they’re not necessarily looking to them as oracles or as leaders of a movement.

I think about what motivates people inside China. I think there are two broad categories: people who realize that what they’re doing now will never be seen in China, but they’re doing it as a message in the bottle to future generations.

For example, one guy I wrote about, Tiger Temple (老虎庙 Lǎohǔ miào), has a very active YouTube channel where uploads all kinds of interviews he’s done with people inside China. Some are now dead, some in prison. His interviews are quite valuable simply as an archive. He did video interviews with survivors of various Maoist campaigns, especially a railway that he helped build as a child laborer. Hundreds of people died. He calls himself Máo Zédōng’s 毛泽东 slave child-labor, though he’s about 70 years old. He’s one of the people who is sending a message in the bottle to future generations to let people know that there were people in Xi Jinping’s China who were still active even if they couldn’t show their stuff inside China, they wanted to get it on record before they pass away, as a resource for future generations to make sense of Chinese history.

Then there are other people who see the Party as not as stable as it was in the past. Increasingly, this is becoming a common view in the West and in non-Chinese societies. We see the problems percolating up in China — a slowing economy, the demographic problems, the homemade diplomatic crises that China has created for itself, alienating vast swaths of the world. While nobody expects The Communist Party to be toppled, because of these weaknesses there are chinks in the armor that allow for alternative visions of alternative versions of reality that make inroads in ways that were not so easy when you had double-digit economic growth. In that era, people were just thinking “Tomorrow’s a better day,” and things like, “What’s the Party? I can afford to buy property, my kid can go to college, so let’s just keep my head down because I can take care of my family.”

When you have a prosperous society, that eliminates 80- or 90% of all potential disputes. Dissidents are challengers to authority in any society, except for the small percentage of people who just have a hair up their ass that commands them to stand up for the few. Once you end up in a situation where prosperity is not being guaranteed and problems arise, then people begin to think, “Gee, this system isn’t working that well.” And then they begin to look for alternative explanations. Some of these people become more valuable, more important, and have more impact. We saw that in the COVID policies, especially in the botched last year of it, 2022 — a pretty bad year for the Party. Rather than being an exception, that could be a precursor for China in the coming decade.

Like Mao and Deng before him, in 2022, Xi rewrote the history of the Party. What was he thinking?

Mao did his rewrite of history in 1945, shortly after he took control of the Party. Mao did a test run, on a history of a Party base in northwestern China, which involved Xi Jinping’s father, who was raised up because of Mao’s rewriting. Mao did the rewriting as a way to cement his own position in the Party. He was still a bit of an outlier at that time. He was charismatic and had just completed The Long March, but many people saw him as illegitimate. He’d never been to Moscow to study at the birthplace of Communism. He had not been endorsed by the Comintern. There were other people who were seen as more legitimate. He used the rewriting of the early history of the Communist Party of China to show the only successful path was Mao’s path. He was able to use this in the subsequent 30 years of his life to knock down potential enemies.

That lasted until Mao died, then Dèng [Xiǎopíng 邓小平] took over and had to explain the fact that all of Mao’s policies were being overturned. How does he explain the complete U-turn on economic policy? In 1981, Deng had to come up with a new version of history which said, “You know, Mao was great but a little bit flawed.” Deng had to explain things like the Cultural Revolution, a period of a lot of turmoil. There were different drafts and people were quite outraged that Communist Party members involved in the drafting downplayed the Great Famine, which, at that point, was just 20 past and still fresh in people’s memories.

Then, Xi does a rewrite in 2022 because it’s been another 40 years and he also needs to essentially overturn the Deng system, which was about political control, economic reform, relative social openness, tolerance, and a kind of quasi-system of transfer-of-power, all of which lasted through Jiāng Zémín 江泽民 to Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛, and then to Xi Jinping.

Now Xi is tossing all this out the window. He’s going to take control permanently, or potentially permanently, or at least for as long as he lives. He also is jettisoning a lot of the economic reforms and everything is becoming subordinate to national security. Xi has to rewrite history to justify his power-grab, just like Mao, and just like Deng. At the same time, they make a very clear point — and Xi warned about this since taking power — that there are these alternative versions of history that are unacceptable, and the Party needs to get rid of them. Xi made that one of his signature policies throughout the 2010s, closing down China Through the Ages (炎黄春秋 Yánhuáng Chūnqiū), a journal his father had endorsed.

Was young Xi Jinping completely shaped by his father’s forced self-criticism, exile, and rehabilitation?

Of course there’s some sort of Freudian analysis. I’m sure he respects his father. On the one hand, he probably thinks his story shows the power of history. His father was raised up by history. His father then lost power because of a historical novel that came out in the Mao era and caused him to be shunted aside for the rest of his career. Deng rehabilitated him, and he played a somewhat important role in the 1980s, but never reached the pinnacle of power again. Xi must have thought, “That might have happened to the old man, but it’s not going to happen to me.”

On the other hand, I wonder if in some way Xi also sort of loathes his father because his father was too weak. His father didn’t come out on top. His father basically lost his battles of history, and that helps explain why Xi made it such a signature policy. I think we sometimes forget what Xi’s policies are — anti-corruption, for sure; a very robust, bellicose foreign policy; control of the economy. Underlying a lot of this is just rewriting history, controlling history, and Xi’s made it much more explicitly important than Hu Jintao or Jiang Zemin did.

Who in American history was like China’s Su Dongpo, the guy who spoke truth to power and paid for it? Was it Tupac Shakur?

I don’t know enough American history, but I think of things like the “Black Wall Street” of Tulsa, which was destroyed in the 1920s in a massive pogrom to destroy black economic power. There probably were historians who knew this and who wrote about this, but they were marginalized. If they ever made the case that Tulsa really mattered, people would look at them like, “Well, from a local history point of view, maybe … if you’re interested in Tulsa history,” or something like that. But now we have realized that this was a central point in a central event: the Jim Crow era suppression of black people between the end of the Civil War and the Civil Rights Movement. Those people who made that argument in, say, the 1940s or 50s, or even the 60s or 70s, would have been looked at like, “You’re a bit off,” or “You’re a bit of a conspiracy theorist,” or, “It couldn’t have been that important.” With a bit of distance, we see.

This raises an interesting point about how we view Chinese history. Some people will sometimes say, “Well, that was all quite a long time ago, you know: the Cultural Revolution, the Great Famine, etcetera.” But think of what motivates Americans: We’re still arguing about 1619, the start of slavery in America. Well, that’s the Ming dynasty. Or the Civil War — that’s the Qing dynasty, around the time of the Second Opium War. And if you talk about Brown vs. Board of Education, desegregation, bussing, Martin Luther King, Jr. — this was all happening at the same time as the Great Leap Forward, the Great Famine, and the Cultural Revolution. Today, again the hot button issue in America is abortion, Roe vs. Wade, right? That’s the Cultural Revolution era. But we don’t think of Roe vs. Wade as ancient history, do we? How can some people say, “Well, how can the Great Famine matter to the Chinese? It was so long ago.” Well, it’s just their grandparents’ generation.

There’s one scene in my book, in a vignette called “Videoing China’s Villages,” when somebody asks a filmmaker, “Why did you ask these people about the Great Famine?” She says, “Well, it formed my grandfather, and that formed my father, and that formed me.” This is inherited trauma, These things aren’t that ancient, actually.

The U.S. held the anti-red Army-McCarthy Hearings in 1954 and Mao started his Anti-Rightist Campaign two years later. Any connection?

It doesn’t require America for Mao to have done what he did. It was a pattern in Mao’s behavior that he was constantly involved in palace intrigues, in making enemies, and fomenting unrest in his own leadership, and then engaging in a series of efforts to keep the revolution percolating along — creating enemies and then attacking them. The Anti-Rightist Campaign is often a little underplayed. People often don’t quite realize how important it was in decapitating China’s intelligentsia. Back then, not that many Chinese people were literate, and there weren’t that many people, and so the Anti-Rightist Campaign was really an effort to bring the intellectuals to heel, an event that’s totally important for understanding the next 50-60 years.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, actual journalism happened in China, empowering reporters to force the Party to admit mistakes. Is there any hope of real, local reporting coming back?

That raises the bigger question: When will China loosen up again? The Party has shown in the past an ability to take corrective measures, but it’s usually after a crisis. So the only reason they made a U-turn after Mao was because of the absolutely abysmal state of China in the late 1970s, when it was still a super poor country and every other country in Asia had leapfrogged ahead of it. The most optimistic scenario I can imagine will be something along the lines of Xi Jinping staying in power for another 10 years, pursuing this state-heavy policy that hobbles the economy and causes more problems for China abroad. There may be further setbacks abroad, perhaps even — but not necessarily — a conflict with Taiwan that China loses, and that eventually, when he dies, he’s replaced by a more moderate person who tries to roll the clock back because they realize that this is the only way for China to really prosper. That’s probably the time horizon you’re looking at but, even then, you’re not talking about a truly open society, you’re talking about a return to the Hu Jintao era or something like that.

You write about Chinese being encouraged to see Mao not for his mistakes, but for his progress. How does China turn the other cheek if organized religion is barred and the Party is the only guide?

I’m just finishing reading Perry Link’s biography of Liu Xiaobo, which reminded me of how, in the last 10 years of his life, he moved past being a problematic character — impetuous, outspoken and rude — and became a better person as time went on. He really embraced the essence of his motto: “I have no enemies.” People would say, “Whaddya mean? They want to throw you in jail! Of course you have enemies! Are you crazy?” He was trying to say he had no personal enemies. In other words, it’s not the police officer who is at fault, individually. There’s no point yelling at him. He’s just a representative of the system. There has to be some sort of reconciliation in your society to move ahead. It can’t just be constantly settling scores, that’s never going to get us anywhere.

In an article the journalist Jiang Xue wrote on January 1 of this year, she quoted Vaclav Havel, who made a famous speech in 1990 that says something along the lines of: “Where did the young people who grew up in the Communist era learn their sense of morality?” The young people in China who participated in the revolution in the late 1980s, where did they come from? They were all products of the system. So there is probably something inherent in humans about a sense of justice and righteousness, something universal that takes various forms, in all cultures and religions, and I think that’s something that people can understand, that can’t be erased.

Has nihilism set in in China, or are young people hopeful?

Just as we saw in the late 1990s, when journalism was liberalized, and there was just a little bit of professionalism injected, you had this amazing outpouring of journalism that took place out of seemingly nothing. You could have something similar arise in the future. There are a lot of young Chinese people involved in stand-up comedy clubs.

What was the origin of your latest book?

I have always reported on grassroots China, and 25 years ago I thought that public intellectuals didn’t really matter. Back then what really mattered was only what was going on at the grassroots in China. My first book, Wild Grass, was specifically not about Liu Xiaobo and grassroots activists. Then I began to realize that this was a bit churlish of me and that, actually, a lot of these people were doing a lot of important things. So I began a Q&A series for the New York Review of Books, “Talking About China,” for which I did over 30 interviews with people talking about this idea of history and the projects that they were working on. That’s what really got me thinking about this book. The very first one I did was with the historian of the Great Famine Yang Jisheng, who is mainly interested in the Mao era. Or there’s another guy, Huang Qi, who was based in Chengdu, where he ran a national hotline for people who were going to petition the government. He had people calling his three cell phones, and on his computer, he’d be blogging. This is also a kind of history, of what was being done — people’s homes being torn down because they were building a high speed rail somewhere, and their whole neighborhood is blasted away and they get no compensation.

When I was writing my book The Souls of China, I went to the wife of Tan Zuoren, the Sichuan environmental activist who did the first documentation of the poor building construction that led to mass deaths in the earthquake in 2008. Ai Weiwei championed him. I began to realize that all this was recent history, and while working on the religion book I knew that Sparks would be my next book. I had it almost all reported when I got expelled in 2020. Unfortunately, the Trump administration’s policies caused the gutting of the US foreign press corps in China, and so I had to leave a little bit earlier than I planned.

Tell us about your expulsion from China.

I quit my day job as a Wall Street Journal correspondent in 2010. I went freelance and the New York Times picked up my accreditation so, in the eyes of the Foreign Ministry, I was a New York Times correspondent, just the same as any staff member. I had the same J-1 Visa, which is a great visa to have because, especially then, a J-1 was a multiple-entry visa lasting a year. As a journalist, the authorities, who hate your guts, always expect you’re going to be looking at sensitive topics, so you don’t have to worry about talking to people.

So I had a journalist visa and we were expecting a child in April 2020. We were going to have the child, then come back to China, then I was going to get my journalist visa renewed and then in 2021, in the spring, we were going to leave, before my visa expired again. I left China to go to London, where my wife was living at the time, for the birth of our child, and I got a call from the New York Times bureau chief, Steven Lee Meyer, who said, “Did you hear about the expulsion of U.S. journalists?” I said, “Yeah, I wondered about that.” And Steven said, “Well, actually, you’re one of them. It’s not just staff members who got expelled, it’s everybody who is on a New York Times, Washington Post, or Wall Street Journal visa.” Anybody working for these outlets who had U.S. passports and whose visas expired in 2020 was expelled. That meant that Jeremy Page, a Brit, stayed, and Keith Bradsher stayed, because Keith’s visa expired in early 2021.

After you were kicked out in 2020, when did you next go back and were you welcomed with open arms by the Foreign Ministry?

I went back earlier this year, 2023 — my first trip back. I didn’t apply for a journalist visa because I’m not really working full time as a journalist. I am still writing articles and freelancing stuff and contributing to the New York Review of Books, and a few other publications, but I’m a staff researcher at the Council on Foreign Relations, so I applied for an F Visa. The consulate asked me, “Are you going to go back and be secretly reporting for the New York Times?” And I said, “No, I’m not applying for a J Visa. That would be illegal. I don’t think any media organization would want that to happen, because that would jeopardize them, and CFR wouldn’t want that because it’d be going in under a false flag. I said, “I’m going to do work for CFR, talk to people to understand China and where it’s heading post-COVID, and I will write something, because think tank people write.” I did a piece for Foreign Affairs on my trip back and what I found out about China.

What did you find out on your first trip back?

It was interesting to go back. I was in Beijing and Nanjing. In a big country, like China, three weeks is not enough to get the whole country, but the advantage of a shorter trip is that, after living in China for 20 years, going back is kind of like watching a soap opera: you’ve missed a bunch of episodes, but because you’ve watched it for so long, you kind of know what’s going on. “Oh, so-and-so’s married,” or “so-and-so’s been killed off.”

I realized that COVID was a real turning point. Things that had already been happening in the 2010s reached their apogee during COVID. It really marked the beginning of a new era in China with a lot fewer foreigners.

We talk about decoupling from China. Well, it feels like China certainly wants to decouple, certainly from the West, and from open societies, including Japan.

Was there one thing that most surprised you on your first visit back?

I had this visceral feeling and understanding of how cut-off China was from the rest of the world. Because I had been in China continuously through the Xi era, I was a bit like a frog being boiled in a pot — I didn’t really realize how hot it had gotten. The changes under COVID, which made things even more explicit, turned up in talks with academics, with people in the street, and in the countryside, and you realize how that era of Gǎigé kāifàng (改革开放, “Reform and Opening Up”) has really ended. It probably ended earlier, but if you want to find a marker, 2020 might be the one. Maybe 2012, when Xi came to power, but in 2020, there was a huge exodus of foreigners and I don’t think they’re coming back in the same numbers, or at least in the same way.

The number of students on this trip was depressing. I went back to one of my old employers, the University of International Business and Economics, where I taught for 10 years, and the number of foreigners is way down. The center where I used to teach has no students right now. I asked “What would be your optimal number?” At their high point they had about 130 students, Americans mostly, and they said “Twenty.” That’s sad, and I think it’s dangerous, because of the lack of understanding

What does Wú Guóguāng 吳國光 mean by rule by “documentary politics”?

China has a National People’s Congress and passes a lot of laws, but it is ruled by circulars, and orders, and documents that are passed down through the bureaucracy, usually by the Central Committee. For example, in 1982, one of the most important religious documents was Document 19, which allowed for the reestablishment of seminaries for priests, and Imam training centers, and temples and schools and churches and mosques. It very explicitly said in 10 pages that while house churches were illegal, the Party didn’t want to crack down too hard. The whole policy toward religion had been too heavy handed and it would go away with time. It said, “We just have to have a lighter touch. If people want to go to worship at the temple, it’s okay to do that.” This document circulated down to every bureau of the government, down to the lowest level. They all got the same thing that said, “Okay, this is what we’re going to do to regulate religious life.”

Essentially it’s rule by law, not rule of law. There’s no collaborative process among different interest groups. Laws are passed, but they are essentially just another form of documentary rule. A document is created and then it’s sent down to be implemented. People often have no incentive to obey. They’re actually very few secrets about how China is run. They’ll have white papers, then they’ll pass the law, and then they’ll pass the implementing regulations and rules on how it’s actually supposed to be carried out. Because there’s no independent judiciary, you can’t just say, “Oh, the courts will decide that.” It all has to be told from the top down.

That’s why things like history resolutions are so important, because they tell everybody who is directly affected — from the local community history center in Anhui to the National History Museum in Beijing — how history should be seen, how you should deal with the Great Leap Forward, how you should deal with the Cultural Revolution, how Reform and Opening Up should be seen. Local officials all read this stuff like marching orders.

Document No. 9, which leaked in 2013, called on CCP members to guard against political “perils” such as constitutionalism, civil society, “nihilistic” views of history, “universal values,” and the promotion of “the West’s view of media.” Is there anything similar you can think of in the West?

No. Document 9 and Document 19 are edicts, probably with some origin in the imperial system where the emperor issued edicts that were then sent down to local levels. In China, there’s the cliche “The sky is high and the emperor is far away.” So, maybe if you get this edict in some remote county in Guizhou, it may not be as important as if you’re in a suburb of Beijing. There is some flexibility in the modern bureaucratic state, which has become much more efficient with digital technologies. In recent years, especially under Xi Jinping, it’s harder to escape the power of these edicts.

The only thing that might be comparable in the U.S. are executive orders, which, in a rather undemocratic way, bypass Congress. Rather than saying, “We’re going to pass a new law about how we restrict trade with China,” we just do some edict, some executive order, and get it done without the people’s participation. Another way to think about it might be, say, a Supreme Court decision that all of a sudden makes abortion legal in 1973 and then, all of a sudden, is reversed in many states in ways that are not really open and transparent.

Is an edict issued with no free press to give it a critical review the epicenter of authoritarianism?

A possible analogy is a papal bull, but even that would have inputs by cardinals. There is input in the Chinese system. Deng’s rewriting of history went through numerous drafts in which he toned down the criticism of Mao.