The China Project Book List — sort by genre: Culture, Society, Memoir

Sort by genre:

Culture/Society/Memoir | Literature | History | Politics | Business/Tech

Sort by time period of primary subject matter:

Ancient and Imperial China | Republican Era to 1949 | Mao to Tiananmen | 1990s to Pre-Olympics | 2008-Present

~

99. Riding the Iron Rooster: By Train Through China

Paul Theroux (Putnam, 1988)

Riding the Iron Rooster is a fine antidote to the colonialist travelogues of the first half of the 20th century, as well as the self-serious immersive reportage books that came to dominate in the first half of this century. Theroux spent a year crisscrossing the country by rail, going as far as Xinjiang in the west and the Shandong coast in the east, often accompanied by government minders. As in all of his travel writing, he is unfailingly human, at turns prickly, lascivious, poetic, or just plain fed-up. If you were lucky enough to take a trip by train in the days before high-speed rail, you will find yourself nodding along in recognition. The off-the-cuff conclusions Theroux tosses out might read as offensive now (he writes off Hong Kongers as philistines and suggests there might be some truth to the idea that Tibetans were descended from a “sexually voracious ogress”), but he has plenty of venom left for the Western tourists, journalists, and businessmen that were flocking to China in the 1980s, and his boorishness is undercut by a natural inquisitiveness that leads to genuine exchanges with the people he meets along the way.

— Dylan Levi King

98. Forgotten Kingdom: Among the Nakhis of Likiang

Peter Goullart (John Murray Publishers, 1955)

This is a valuable first-person narrative from an author who spent almost a decade in Lijiang, Yunnan Province during the 1930s and 1940s. Originally a tour guide in Shanghai, the Russian-born Peter Goullart eventually became appointed by the Nationalists as chief of the Chinese Industrial Cooperatives in Lijiang, where he learned to speak Naxi, the language of the dominant ethnic group. Descriptions of his encounters with local traders, merchants, and inn keepers are sensational (like the time a Muosuo woman offered herself as “payment” for medicine), and it’s hard to believe that the story of his kidnapping by upland bandits wasn’t embellished. Still, Goullart’s highly attuned descriptions of the Han Chinese, Tibetans, Nakhi (Naxi), and Lolos (Yi) merchants from all walks of society present a vivid portrait of an ethnically diverse southwest China during a pivotal time in the country’s history.

— Rosalyn Shih

96. Iron and Silk

Mark Salzman (Random House, 1986)

Mark Salzman was among the first generation of Americans to teach in China, in the 1980s, when he was in Changsha. His was by no means the average waiguoren (foreigner) experience; Salzman was already fluent in Mandarin (and conversational in Cantonese) when he arrived, and he was an expert in wushu. He’s a sharp observer, and he tells his story through vignettes that are both beautiful and brief — actually, there is something Daoist in his economy. The China that he depicts is something of a lost world — it’s hard to grasp how poor and isolated places like Changsha were at this time. After China, Salzman went on to a great career as a novelist and memoirist, with an impressive range of subjects. But he never returned to China after filming the movie version of Iron and Silk in 1989.

— Peter Hessler

94. Unnatural Selection: Choosing Boys Over Girls, and the Consequences of a World Full of Men

Mara Hvistendahl (Public Affairs, 2011)

China has no shortage of problems on its horizon, but perhaps one of the most alarming and underappreciated is its severe gender imbalance, which will see tens of millions of men go permanently without a female partner. In this book, journalist Mara Hvistendahl traces the origins of the problem, from Western fears of overpopulation in the 1960s though the present day, where a patriarchal culture, strict birth limits, and sex-selective abortion have made China ground zero for this problem with global implications. Hvistendahl’s vivid character-driven storytelling combined with her experience as a science reporter shine through, as she draws on extensive interviews, scientific research, history, and sociology to give a fascinating page-turner into how the problem developed and what its future implications may be. From increasing crime rates, human trafficking, and rising housing prices to the potential for more hawkish nationalism and social instability, she notes that, “Historically, societies in which men substantially outnumber women are not nice places to live. Often they are unstable. Sometimes they are violent.” This book is the go-to resource for understanding one of China’s greatest challenges, which will continue to strain the country in both obvious and subtle ways for decades to come.

— Eric Fish

91. Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China

Paul French (Penguin Books, 2012)

The story of 19-year-old Pamela Werner’s grisly murder and postmortem dismemberment and dissection in 1930s Peking was mostly forgotten by the time Paul French began investigating the story in the mid-2000s. French sets his reconstruction of the events of 1937 against the backdrop of a city and a nation on the verge of monumental change. The novelistic retelling of the Werner story is as compelling as French’s portrait of Peking in the dying days of Old China, and the city’s collection of expatriate misfits, colonial holdouts, weirdos, and perverts.

— Dylan Levi King

89. The Good Women of China: Hidden Voices

Xinran (pen name for Xuē Xīnrán 薛欣然), translated by Esther Tyldesley (Chatto and Windus, 2002)

If you’ve ever flipped through FM stations in a Chinese city late at night, you’ve likely heard this: a woman’s voice, coming down a phone line, sharing private pain and unimaginable suffering. Xinran helped pioneer the format on her Words on the Night Breeze program, and the stories in The Good Women of China are mostly drawn from letters she received while hosting the show. Xinran does her best to pry open the trapdoor to what still goes unspoken. The stories she collects of rape, incest, domestic violence, forced abortion, kidnapping, and suicide are shocking — but even more shocking is the seeming mundanity of the brutalization of women and girls, sometimes by less extreme but far more insidious means. Perhaps Xinran could be faulted for trying too hard to pin the case on political and social chaos under the Communist Party; still, the stories she relates — including her own — are timeless and depressingly universal.

— Dylan Levi King

87. Life and Death in Shanghai

Nien Cheng (Grove Press, 1987)

The 1980s witnessed a publishing boom in English-language (or translated) China memoirs that focused on individual experiences of political campaigns from the 1950s through the Cultural Revolution. Nien Cheng’s Life and Death in Shanghai stands out in a crowded and exceptional field that includes Wu Ningkun’s A Single Tear, Yue Daiyun and Carolyn Wakeman’s To the Storm, Gao Yuan’s Born Red, and Yang Jiang’s A Cadre School Life: Six Chapters. When the Cultural Revolution began, Nien Cheng worked in a senior position at the British Shell oil company in Shanghai with the blessings of the Shanghai Communist Party, which also had allowed her and her late husband — a former Kuomintang diplomat who was invited to work with Shanghai’s new government — to keep their grand house and servants. Overnight, she became an accused British spy and enemy of socialism. Condemned to six and a half years in prison, she endured physical and psychological torture and deprivation. Her beloved daughter, meanwhile, committed suicide. Cheng is a sharp observer and a gifted storyteller; her fierce intelligence, wit, and courage are evident on every page. When the book came out, some critics carped that her status as a wealthy bourgeois rendered her story “untypical.” I’d argue that her strength of character, her unbending spirit, and her search for justice make it universal.

— Linda Jaivin

85. With Love and Irony

Lín Yǔtáng 林语堂 (Blue Ribbon Books, 1945)

This collection of essays from social commentator and polyglot Lin Yutang — a Chinese scholar with the rare gift of being able to address a Western audience in plain English prose — is a phenomenally digestible primer on “the Chinese,” an attempt by the author to dispel the image of inscrutability and exoticism which dogged public perceptions of China at the time (and, regrettably, still does to this day). Lin could perhaps be called one of the first anti-Orientalists, but also a debunker of the Yellow Peril.

Despite being written at a time when China was fractured, subjugated, and ablaze, this book is replete with good-humored musings on the habits and thinking of the “average Chinese,” a man (sadly, Lin’s views on women are not ahead of its time) who prefers goldfish and canaries to guns and cannon, and who doesn’t need to be “right” to win an argument with a neighbor —- merely “reasonable.”

One can derive comfort from Lin’s genial assessment of the Chinese as, ultimately and eternally, “reasonable people leading reasonable lives.” He paints a picture of a people too thoughtful for demagoguery, too placid for warfare, too happy-go-lucky for ruthless exploitation of others. His words speak to those of us who try to square the reality of our intellectually dynamic, generous, and open-minded Chinese friends with their monolithic state, and remind us that there is indeed a difference.

— Jack Smith

83. The Web That Has No Weaver: Understanding Chinese Medicine

Ted J. Kaptchuk, O.M.D. (Congdon & Weed, 1983)

First published in 1983, this book is a classic introduction to Chinese medicine that is equally well-suited for an acupuncture training course, a university philosophy class, or the bedside table of anyone interested in Chinese culture. Its author, Ted Kaptchuk, is a Harvard professor who studied traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in Macau and is also known for his work on the efficacy of placebo effects in medical treatment. In addition to what you might expect from a guide to Chinese medicine — for example, explanations of various kinds and capacities of qi, pulse-taking, and careful comparisons of Chinese and Western notions of the body, illness, and healing — this book delves deep into the practical and philosophical roots of TCM, from the five aspects of the spirit to yin/yang oscillations to poetic (yet rigorous) meditations on landscape painting, the senses, and nature. Ultimately, this book is an ontological sketch of the Chinese universe. By taking this system of thought and practice and animating it for foreign readers, Kaptchuk challenges the notion that Western science has “a unique handle on the truth — all else is superstition.”

— Hanna Pickwell

80. Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China

Leta Hong Fincher (Zed Books, 2014)

It is a truth universally acknowledged that when a student opens a Chinese history textbook that addresses the status of women in Communist China, they will be confronted with one of Mao’s most famous utterances: “Women hold up half the sky.” What is less certain is whether that same text will talk about everything that women have endured in the many decades since. Leta Hong Fincher’s seminal work, Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China, lays out in no uncertain terms just how empty that platitude rings for Chinese women in the contemporary era. Devastating in its forthrightness, Hong dissects the rise of the demeaning term “leftover” (or 剩女 shèngnǚ, leftover women) to shame young women into marriage and childbearing — regardless of their own personal dreams for higher education or professional success. Hong also captures the political and social background that contextualizes precisely how women are kept from advocating for even the most basic rights, such as protection from abusive partners and economic exploitation.

Written in the years leading up to the Feminist Five incident and the #MeToo movement, Leftover Women lays the groundwork in a clear and unflinching way for understanding the cataclysmic events that have reshaped the landscape of contemporary Chinese feminism. Time may be up for tired maxims about holding up half the sky, but for Chinese feminist activism, Hong’s work proves that things are just getting started.

— Siodhbhra Parkin

78. Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper: A Sweet-Sour Memoir of Eating in China

Fuchsia Dunlop (W .W. Norton & Company, 2008)

The mouthwatering spice of noodles, the chaos and stench of a wet market, the surprisingly rubbery crunch of intestines, and more…all described in savory detail — beware, Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper may well trigger your visceral sensations. Author Fuchsia Dunlop’s personal story begins like it does for many expats, as a student exploring a Chinese city. But, as detailed in this memoir, after she enrolls in the Sichuan Institute of Higher Cuisine — the first-ever foreigner to do so — she begins a decades-long journey traversing the country in search of discovery, understanding, and good food. Along the way, she becomes one of those rare Westerners in China to achieve true culinary enlightenment, able to enjoy the bits and pieces that the rest of us merely politely endure. Through personal anecdotes and historical research, she places the vast and varied world of Chinese cuisine into much-needed context, and — as a bonus for us — ends each chapter with a recipe. I recommend this book to anyone, but especially to those who see the “eccentricities” of the Chinese diet as an opportunity to explore, to learn, and to challenge one’s own preconceptions.

— Jessica Colwell

74. Six Records of a Floating Life

Shěn Fù 沈复, translated by Leonard Pratt and Chiang Su-Hui (Penguin Classics: Harmondsworth, 1983)

This is an early 19th-century book that crosses genres, blending memoir and novel to give us a portrait of a mid-level official and his relationship with his dear wife, who dies young. It’s a very accessible, short work, partly because four of the six records are lost. When I was first getting interested in China I read it and it sort of brainwashed me, in a very good way, making me realize the universality of ambition and disappointment, love and sadness, among people around the world. I feel that these kinds of books, which tell us about how people really live their lives, often in microscopic detail, are more lasting and telling than the usual “must-read” China books, which have a shelf life of a few years. They get under your skin and stick with you, which is what great writing should do.

For many Chinese readers, it’s also been an inspiring work. For example, the writer Yang Jiang used it as a loose template to record her time with her husband, the novelist Qian Zhongshu (Fortress Besieged), in a labor camp (A Cadre School Life: Six Chapters).

— Ian Johnson

70. Décadence Mandchoue: The China Memoirs of Sir Edmund Trelawny Backhouse

Sir Edmund Trelawny Backhouse, edited by Derek Sandhaus (Earnshaw Books, 2011)

Sir Edmund Backhouse is a reflexively interesting character. He was a reclusive linguistic genius and an English dandy, the best-selling chronicler of the late-Qing Dynasty and a literary fraud, the alleged lover of Oscar Wilde and the Empress Dowager Cixi. Who wouldn’t want to read that autobiography? The two-odd years I spent decoding his handwritten memoirs — a dense thicket of polyglottal meanderings, contradictory claims, and byzantine literary allusions — were as mad and exasperating as any an editor is likely to encounter. But I wouldn’t have traded the experience for anything, because Décadence Mandchoue is a book unlike any other.

It is not a book for everyone. Many struggle to navigate its dense prose and baroque sexuality, and the line between reality and fantasy is blurred to the point of indecipherability. Yet readers who follow where its author leads — through the gay brothels of Qianmen, the seat of Manchu power, and the Forbidden boudoir — will glimpse a salacious but poignant portrait of a forgotten China.

— Derek Sandhaus

68. Red China Blues: My Long March from Mao to Now

Jan Wong (Doubleday Anchor Books, 1996)

Jan Wong’s memoir of China in the 1970s and ’80s is mostly forgotten outside of her native Canada, where she is more famous for a column dishing dirt on Toronto celebrities. But it presents a unique twist on the genre of books written by foreigners on sojourn in the Middle Kingdom. Red China Blues charts Wong’s first visit to China in 1972 as a student fired up by Maoist fervor, her attempts to learn Chinese while also hauling pig manure, her marriage to Norman Shulman, an American draft dodger, her disillusionment with the excesses of the Cultural Revolution, and then her eventual return to China as a foreign correspondent for the Globe and Mail. She arrived back in Beijing just in time to have a front row seat for the earth-shaking events of the summer of 1989. The book attempts to make sense of the political upheaval of the past half-century and her own connection to her ancestral homeland.

— Dylan Levi King

62. Socialism is Great!

Lìjiā Zhāng 张丽佳 (Atlas, 2008)

Much has been written about the personal tragedies experienced during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) and the 1989 student demonstrations, but there is too little about the lives of individuals during the intervening period. Socialism is Great! is one of the few English-language memoirs that bridges the gap. Chinese author Lijia Zhang came of age working in a Nanjing rocket factory in the 1980s as the country was emerging from the tatters of the Mao era and starting to embrace a more capitalistic and open society, albeit under still-draconian social controls. Like many of her generation, this small opening allowed Zhang to break with the ideological constraints that had defined her parents’ cohort and embrace more individualistic desires. From a growing fascination with Western culture to forbidden sexual rendezvous, Zhang gives an honest and beautifully written reflection of life in a society that wasn’t quite ready for a free spirit like her. Regardless of one’s interest in China, this book is a wonderful coming of age memoir, but it’s especially valuable for the China enthusiast. In reading, one gets a feel for the sorts of experiences and influences that gave 1980s youth just enough that many realized they wanted even more, and those desires began to outpace what their government was willing to allow. To wit, the book concludes with Zhang becoming a protest leader in the 1989 student movement.

— Eric Fish

59. The Corpse Walker: Real Life Stories, China From the Bottom Up

Liào Yìwǔ 廖亦武, translated by Wen Huang (Pantheon, 2008)

Many years before being branded a professional dissident, Liao Yiwu was a Chinese state-authorized poet. But his outspokenness over the Tiananmen student protests landed him in jail, and upon his release, he found himself abandoned by his wife, ostracized by acquaintances, and thrust into the bottom rungs of society. During this time, part of it wandering the streets of Chengdu, he compiled stories — via interviews — of China’s underclass, talking to a leper, a musician, a former Red Guard, a grave robber, a Falun Gong practitioner, and more. Sixty interviews were collected and published in Taiwan in 2001; 27 of those were translated for The Corpse Walker, which remains Liao’s representative English-language work.

Liao didn’t take notes while his subjects spoke, but he captures their voices and tries his best, where applicable, to preserve something of their human dignity. “I used to drive a human-waste truck,” a bathroom attendant says. “Nobody looked down on me because I was handling shit.” Liao himself is very much part of the dialogues, as when he tells a slick-talking human trafficker, “If I were the judge, I would first cut off your tongue as punishment.” The title story is about professional mourners who literally walk corpses from the world of the living into the world of the dead. “People in the countryside still believe that the fake money is used to bribe the corpse’s guardian ghosts so they don’t block the road to heaven,” Liao’s interviewee says, to which Liao quips: “So people used to think the world of the dead was equally corrupt.”

— Anthony Tao

56. Our Story: A Memoir of Love and Life in China

Ráo Píngrú 饶平如, translated by Nicky Harman (Pantheon, 2018)

Rao Pingru was 87 when he began to write the story of his life, focusing on his long marriage to his recently deceased wife, Meitang. In the absence of surviving photographs, he taught himself to paint, and so it is that Our Story is illustrated with his charming, quirky pictures.

Born in 1922, Rao received a Confucian education, and acquired an abiding love of classical Chinese poetry. As a young man, he fought in the anti-Japanese War (he paints the bloody battles vividly), escaping death by a whisker on several occasions. When peace came, his father arranged his marriage to Meitang. Rao gives us fascinating glimpses of the life they led in the late-40s and early-50s: their travels around China, local food specialities (illustrated in great detail), and his desperate attempts to find a job. Eventually, the couple settled in Shanghai, where he worked as an editor and they raised five children — before he was sent away to do reform through education during the Cultural Revolution. In the last part of the book, Rao describes in heartbreaking detail how he cared for Meitang as she battled diabetes and dementia, and mourned her death.

Rao became a TV celebrity when Our Story was first published in Chinese. He is now 97, and recently appeared at the Shanghai International Literary Festival.

— Nicky Harman

52. Little Soldiers: An American Boy, a Chinese School, and the Global Race to Achieve

Lenora Chu (Harper, 2017)

Chinese American reporter and writer Lenora Chu and her husband, both based in Shanghai, made a bold decision for their young son: They enrolled him in one of the most competitive, high-performing schools in one of China’s most hyper-competitive, education-obsessed cities. The results are recorded with great candor and humor in Chu’s book. Little Soldiers is not, however, a simple screedo against rigid Chinese pedagogy. Instead, as she follows the lives of not only her son but of other Chinese students, Chu looks critically at both the Chinese and U.S. education systems and offers many important insights.

— Kaiser Kuo

51. The Most Wanted Man in China: My Journey from Scientist to Enemy of the State

Fāng Lìzhī 方励之, translated by Perry Link (Henry Holt and Company, 2016)

A world-renowned astrophysicist and a tireless advocate for freedom and democracy in China, Fang Lizhi was labeled “the biggest blackhand” behind the Tiananmen Square protests by Chinese authorities, and sought refuge in the U.S. embassy after the crackdown. During the 13 months he and his physicist wife spent at the embassy before they were allowed to leave China, Fang wrote a memoir, recounting his life with grace, candor, and disarming wit. From his boyhood in wartime Beijing to surviving Mao-era campaigns, from pioneering modern cosmology amid political pressure to championing human rights on the path of dissent, Fang’s formidable intellect and humane spirit shine through every page. Masterfully translated by Perry Link, a longtime friend of Fang’s, and published after Fang’s death in 2012, the book is a rare first-person account of life in the People’s Republic during its tumultuous first four decades, an important examination of science’s role in an authoritarian state, and a compelling lesson in universal values as fundamental as the laws that govern the stars.

— Yangyang Cheng

47. The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa

Deborah Brautigam (Oxford University Press, USA, 2011)

The first major work to take on the question of China’s impact in Africa, Brautigam’s book tends to accentuate the positive, as its title suggests. She builds on the insight that what China has done in Africa — infrastructure-for-resources deals, where China for instance builds a copper mine, a railway to the coast, and a container port and takes payment in copper until the debt is paid — is exactly what Japan did in China in the 1970s and 1980s, and the success of such projects in driving development in China is the rationale behind China’s initiatives in Africa. She takes on common critical tropes one hears in the West — debt-traps, enabling of kleptocrats and tyrants, neo-colonialism — with an impressive command of data.

— Kaiser Kuo

45. One Child: The Story of China’s Most Radical Experiment

Mei Fong (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016)

One Child follows the twists and turns of China’s most notorious social experiment: the planned birth policy instituted in 1980. Limiting families to a single offspring may have seemed prudent at the time, when China’s population was growing at alarming rates, but in reality, that decision carved out immense challenges for Chinese individuals as well as the world’s most populous country. For example, there’s Zhu Jianming, who had a reverse-sterilization operation just weeks after the death of his only child. His story illustrates the despair that accompanied the policy’s forced abortions and sterilizations. Yang Libing’s daughter was seized by family planning officials and placed on the global adoption market, a story that touches upon the corruption and human trafficking the policy fostered. And Liu Ting’s story is a harbinger of China’s future, when a generation will age out of the workforce amid a shrinking population. A former Wall Street Journal reporter out of Beijing, Mei Fong meticulously researched and documented these stories over the course of five years. One Child harkens back to an era that seems bygone — Chinese are now allowed two children — yet understanding the long-lasting effects of China’s social planning experiment is more important than before, as the country’s status grows ever larger on the global stage.

— Lenora Chu

39. The Emperor Far Away: Travels at the Edge of China

David Eimer (Bloomsbury USA, 2014)

For every hundred tedious China memoirs or airport books with a play on words about dragons in the title, there is a book like David Eimer’s. The Sunday Telegraph’s former man in Beijing set himself a tougher task than most: traveling through the borderlands, meeting the ethnic minorities that call them home, and attempting to get a feel for the “huge, unwieldy and unstable empire that is China.”

Eimer’s book details his visits to Xinjiang, Tibet, Yunnan, and then Dongbei (the country’s northeast). The timing was right, since many of the areas that Eimer visited between 2007 and 2012 are now either nearly impossible for foreigners to access or have been swamped by tourism and investment from the center. Eimer is not an expert, but his keen eye for detail makes him an excellent reporter on regions few outsiders get to experience. He also knows when to shut up and let the story happen to him — he knows, when a United Wa State Army chief offers you a meth pipe, etiquette dictates you smile and take a rip.

— Dylan Levi King

32. Peking Story: The Last Days of Old China

David Kidd (Aurum Press, 1988)

A book that remained fairly obscure until being picked up for reissue by the New York Review of Books’ publishing wing, Kidd’s Peking Story is one of the truly unique records of a foreigner in China. Kidd arrived in Beijing (then known as Beiping) at a moment of great change, two years before the city fell to the Communists — bad timing for an aesthete in love with the material culture of the Old China, even worse timing for a man married into an aristocratic Manchu family. He writes odes to the silks, bronzes, and elegant paintings that furnish the mansion of the Yu family, then watches all of it tossed into the fire and the aristocrats turned out into the street. The son of a Kentucky coal boss, raised in Detroit, the tale of Kidd is just as captivating as the story of aristocratic collapse. The details of Kidd’s later life and the fact that several of his contemporaries have raised concerns about the accuracy of Kidd’s account only adds to the mystery.

— Dylan Levi King

30. Nine Continents: A Memoir In and Out of China

Xiǎolǔ Guō 郭小橹 (Grove Press, 2017)

Xiaolu Guo was introduced to Anglophone readers by Cindy Carter’s translation of Village Of Stone in 2005. It was impossible not to read the autobiographical novel of a girl escaping to the city without wanting to know more about the author’s own life. Guo returned to the autobiographical with her first novel written in English, A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary For Lovers, which was based on her own expatriation to London in 2002. Turning to memoir made perfect sense, but few Chinese writers, with the exception of old-guard heavyweights and those in exile, ever produce novel-length memoirs. That makes Guo’s Nine Continents even more special. She writes of her childhood, growing up in miserable poverty in a fishing village in the 1970s before escaping to follow her dreams at Beijing Film Academy, then in England, and her experience of motherhood and return from self-imposed exile. Guo’s story of overcoming her background to seek her dreams is — especially in China — not unique, but her perspective is one we are rarely given access to; and her talents as a writer make this an essential story of the Chinese experience.

— Dylan Levi King

24. The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao

Ian Johnson (Pantheon, 2017)

The Souls of China brings the reader face-to-face with the practitioners of a variety of spiritual traditions in China. Ian Johnson describes in vivid detail such experiences as Buddhist temple pilgrimages and festivals on the outskirts of Beijing, Daoist and folk religion practices in Shanxi Province, and the politics of protestant Christian house churches in Chengdu, Sichuan. Not all of religion and spirituality in China is covered here, but enough of it is, and the description and context given is so illuminating that the book, taken as a whole, communicates a compelling message about the direction of China’s national “soul” today. In short, although the lines of religion, spiritual practice, and “culture” are blurred — sometimes intentionally by the state — the Chinese people are responding to a genuine spiritual and moral vacuum created by many decades of state-led destruction and economic dislocation.

— Lucas Niewenhuis

22. The Last Days of Old Beijing: Life in the Vanishing Backstreets of a City Transformed

Michael Meyer (Walker & Company, 2008)

The Peace Corps program in China produced Peter Hessler, whose River Town and Oracle Bones are justly celebrated, but Michael Meyer’s three books of immersive reportage (The Last Days of Old Beijing, In Manchuria, and The Road to Sleeping Dragon) are equally worthy of acclaim. The Last Days of Old Beijing, Meyer’s first book, is a dispatch from a hutong near Dashilar in central Beijing, ground zero of the city’s aggressive transformation in the run-up to the 2008 Olympics. Meyer describes his life in his rented room and his job at a local school, but rather than being yet another solipsistic China memoir, The Last Days is refreshingly analytical and unsentimental, teasing out the political economy of the backstreets, reporting on the attempts at saving heritage buildings, and sketching the lives of his neighbors. Reading the book less than a decade on, it’s jarring to think that much of what he described is already gone.

— Dylan Levi King

21. Wild Swans

Jung Chang (Harper Collins, 1991)

This book will always have a special place on my shelf. I was 12 years old when I first read it, probably too young for some of its content — it is known as “scar literature,” after all, part of a category of books penned after the Cultural Revolution in which authors shared the pain suffered by the people during the 1960s — but it gave me my first glimpse of a culture and history I knew nothing about. I’m sure that’s the case for many readers: It is now a global phenomenon, having sold more than 13 million copies in nearly 40 languages. Wild Swans is often categorized as nonfiction, but it reads like a literary novel. I absolutely recommend it for anyone who wants to learn more about China’s tumultuous 20th century, as told through the eyes of three generations of Chinese women who survived it.

— Manya Koetse

17. China’s Second Continent: How a Million Migrants Are Building a New Empire in Africa

Howard French (Knopf, 2014)

China’s growing presence in Africa has been a hot topic for years, with rival camps staking out positions on so-called debt trap diplomacy, on allegations of neo-colonialism, or exploitative resource extraction, or unfair labor practices. What gets overlooked too often is the lived experience of ordinary people, whether Chinese or Africans. Howard French, a veteran reporter with the New York Times, with extensive reporting experience in Africa and in China, addresses this gap in an excellent book that profiles, with great sensitivity and sympathy, a number of Chinese living and working in countries around Africa. Their personal stories go far toward a better understanding of China’s ambitions as well as its challenges. French has the rare combination of experience, reporting skill, and writing chops that make this book essential reading for anyone seeking to make sense of China’s extensive involvement in Africa.

— Kaiser Kuo

12. Oracle Bones: A Journey Through Time in China

Peter Hessler (Harper, 2006)

In 2002, Peter Hessler followed up River Town, his account of teaching young people in Fuling in the late 1990s, with a book that delves deeper into greater contemporary China. He starts at both ends, as it were; he goes right back to the oracle bones of the book’s title, the system of divination that dates back more than 3,000 years, and then interpolates history with descriptions of how his former college students have progressed since graduation, and interviews numerous other ordinary people whom he meets as he travels around China. Reviewers have commented that the format is over-ambitious, that inevitably in a single book, Hessler can only touch on limited aspects of China’s history, culture, and contemporary development, and that his choices are “random.” But what almost all readers agree on is that he has a beguiling ability to relate to ordinary folk and relate their lives. It is interesting to note that his style of longform journalism has attracted a great deal of admiration in China. In the words of one writer, “Chinese people worship Hessler,” and many of his books have been translated into Chinese.

— Nicky Harman

11. Out of Mao’s Shadow: The Struggle for the Soul of a New China

Philip P. Pan (Simon & Schuster, 2008)

Out of Mao’s Shadow is a tribute to survivors: the Chinese who persevered through famine, revolution, shattered idealism, and the inversion of values systems. It is a profile of the Chinese national character, of brave men and women whose struggles exemplify the enduring human spirit. Philip Pan, who reported for the Washington Post for eight years in Beijing, interviews lawyers, activists, doctors, officials, and everyday people, and tells on-the-ground stories about SARS, censorship, politicians, martyrs, and more. Two profiles in particular stand out: The first is on Hu Jie, a man obsessed with Lin Zhao, a girl imprisoned during the Cultural Revolution who legend has it wrote on the walls with her own blood; the other is on Chen Guangcheng, a blind lawyer harassed by authorities and goons in his rural village. (Chen would capture international headlines years later when he escaped house arrest, turned up at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, and was eventually granted permission — after high-level negotiations — to leave for the U.S.)

It’s hard to read Out of Mao’s Shadow and not come away marveling at the Chinese people and thinking that the state could benefit from celebrating its most colorful and intrepid characters. Alas, reading this book 11 years later, it’s perhaps more appropriate to wonder who will continue to take up the struggle as the void left by Mao’s death becomes increasingly filled with money and power. How much soul is left to struggle for?

— Anthony Tao

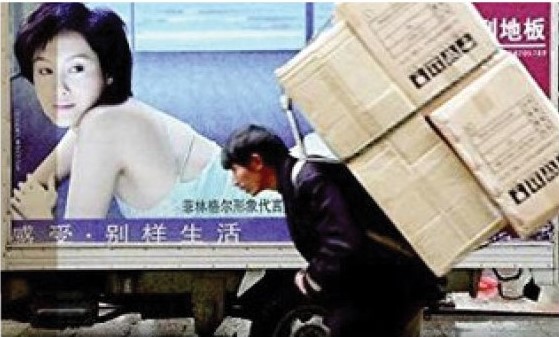

10. Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China

Leslie T. Chang (Spiegel & Grau, 2007)

I can’t tell you how many times people have mistaken me, a former factory girl who wrote a memoir about my experience (No. 62 on this list), for Leslie Chang, the author of Factory Girls. I always say I’m flattered, but I have to disappoint them. It so happens that Factory Girls is one of my favorite books about contemporary China.

A former correspondent for the Wall Street Journal, Chang is brilliant in providing social and economic context, but Factory Girls goes much deeper. Her book is an intimate and powerful portrait of young migrant workers in Dongguan, a giant manufacturing base in southern China’s Pearl River Delta, where women account for 70 percent of the labor force. The city is “a perverse expression of China at its most extreme,” as Chang writes. The girls in Dongguan leave their home villages to venture out to the city because “there’s nothing to do at home.” They fill out the production lines in one of hundreds of factories. In the feverish and chaotic city, they switch friends as frequently as they change jobs. They go to night schools to better themselves as slogans tell them that “to die poor is a sin.” These factory girls are really the unsung heroes of China’s economic miracle.

— Lijia Zhang

9. Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China

Evan Osnos (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014)

Age of Ambition is itself an ambitious book, aiming to capture the essence of contemporary China through a diverse set of people that Evan Osnos met during his eight years in the country, where he was a staff writer for the New Yorker. What Osnos achieves is a compelling series of snapshots of 21st-century China, threaded together by each character’s burning desire to change their fortunes. Part of this book’s achievement is its treatment — with equal respect — of outliers such as Ai Weiwei and ordinary people like internet entrepreneur Gong Haiyan. After all, they all have something valuable to say, and are all part of the “real China” story. In one particularly entertaining vignette, Osnos joins a Chinese tour group on a holiday to Europe; for him, the explorers are absurd, but also poignant and proud. You’ll find yourself laughing with them, and cheering them on as they pursue their grand, sometimes quixotic ambitions.

— Amy Hawkins

3. China Pop: How Soap Operas, Tabloids and Bestsellers Are Transforming a Culture

Jianying Zha (The New Press, 1995)

Published six years after the Tiananmen massacre, China Pop’s opening page sees Jianying Zha making a bold and refreshing request for readers to consider China outside the shadow of June 4, 1989. The proposition is all the more powerful because so very few people are able to write as authentically and piercingly on that subject. An example from the book:

We are the golden children who went astray, the delicious promise that turned sour, the little angels who somehow grew horns on our heads. Our lesson about history is that it should never be repeated. It’s an important lesson to keep in mind — but how can we reasonably expect others to carry this burden or feel the same way about our past? After all, hadn’t we bitterly resented our parents for clinging to their own history? Our younger siblings have little recollection of the Cultural Revolution. Our children will have no memory of Tiananmen. They may read about these events in the history books, see them in films, hear stories about them at dinner tables. So we hope. But they probably won’t share our intensity about them. They will have a lightness of spirit about life that doesn’t come naturally to us. Or so we hope.

Zha’s gifts as a witness and writer are to be envied; in China Pop, she repeatedly exercises her special ability to tap into the country’s collective conscience without resorting to armchair psychoanalysis or excuse-making. The book feels uniquely hers: It is filled with pop culture references and Chinese proverbs (“If the fish likes what’s on the hook, well then, fishing is fair play”), interviews with film directors and authors — Chen Kaige, Jia Pingwa, Chan Koonchung, Wang Shuo, etc. — rock stars and intellectuals, and observations about transformation and loss, Hong Kong and cassettes (“Red Sun, an adaption of famous old hymns praising Mao to soft rock rhythms with electronic synthesizers”), McDonald’s and porn. China Pop is an unvarnished document of an era, filled with evocative and wry reflections on a generation of Chinese I wish we could hear more from. They speak loudly in this book, and memorably.

— Anthony Tao

The China Project Book List. Back to main Books List page