The China Project Book List — time period: 1990s to Pre-Olympics

Sort by genre:

Culture/Society/Memoir | Literature | History | Politics | Business/Tech

Sort by time period of primary subject matter:

Ancient and Imperial China | Republican Era to 1949 | Mao to Tiananmen | 1990s to Pre-Olympics | 2008-Present

~

97. Shanghai Baby

Wèi Huì 卫慧, translated by Bruce Humes (Deckle Edge, 2001)

This controversial Chinese novel tells the story of Coco, a Shanghai waitress in search of love, whose ambition it is to become a famous writer. Shanghai Baby focuses on city life and the sexual awakening of the young socialite, containing many sexually explicit scenes of Coco’s encounters with her Chinese and foreign boyfriends. Within China, this book was officially banned in 2000, with 40,000 copies publicly burned. Outside of China, it was either marketed as “that banned book” or as some Chinese equivalent of Sex and the City — often leaving foreign readers disappointed when their expectations weren’t met. Shanghai Baby isn’t considered a literary masterpiece, but it shouldn’t be categorized as chick-lit, either.

Because of all the controversy and misconception, I decided to write my thesis in Literary Studies about this book years ago, arguing that it needs to be put back in its context of the PRC in the late 1990s. Wei Hui was one of the pioneers of the so-called “beauty writers” (美女作家 měinǚ zuòjiā) wave, together with authors Mian Mian (Candy) and Chun Sue (Beijing Doll): young urban women authors who were not afraid to write about unconventional lifestyles and sexual experiences. What they did was bold, especially in 1990s China, giving voice to a new generation of strong, independent Chinese women.

— Manya Koetse

88. The Beijing of Possibilities

Jonathan Tel (Other Press, 2009)

Over the course of 12 short stories, Jonathan Tel conjures a vibrant, complex Beijing of multitudes, of idealists and thieves, migrant workers and musicians, of surreal twists and fantastical elements nevertheless grounded in the possible. Tel’s Beijing is one where a gorilla mascot is subjected to Cultural Revolution-style torment in advance of the Summer Olympics, where a boy goes on a Monkey King-like adventure to procure a cotton candy machine, and where a girl with runaway dreams transforms into a modern-day Cinderella. This is the Beijing I imagine telling people about when I talk to those who have never been here. “How wonderful to be alive in the Beijing of possibilities,” thinks the girl in the title story. I believe that sentiment, in the same way people believe in great fiction.

— Anthony Tao

78. Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper: A Sweet-Sour Memoir of Eating in China

Fuchsia Dunlop (W .W. Norton & Company, 2008)

The mouthwatering spice of noodles, the chaos and stench of a wet market, the surprisingly rubbery crunch of intestines, and more…all described in savory detail — beware, Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper may well trigger your visceral sensations. Author Fuchsia Dunlop’s personal story begins like it does for many expats, as a student exploring a Chinese city. But, as detailed in this memoir, after she enrolls in the Sichuan Institute of Higher Cuisine — the first-ever foreigner to do so — she begins a decades-long journey traversing the country in search of discovery, understanding, and good food. Along the way, she becomes one of those rare Westerners in China to achieve true culinary enlightenment, able to enjoy the bits and pieces that the rest of us merely politely endure. Through personal anecdotes and historical research, she places the vast and varied world of Chinese cuisine into much-needed context, and — as a bonus for us — ends each chapter with a recipe. I recommend this book to anyone, but especially to those who see the “eccentricities” of the Chinese diet as an opportunity to explore, to learn, and to challenge one’s own preconceptions.

— Jessica Colwell

71. Beijing Comrades

Běi Tóng 北同 (pseudonym), translated by Scott E. Myers (The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2016)

Written by an anonymous author in 1998 and first published as an online novel, Beijing Comrades tells a love story between two men against the backdrop of political and economic upheaval in 1980s Beijing. Handong, an unsympathetic business man with political connections, falls for Lan Yu, a young, seemingly naive newcomer to the Chinese capital. Over 384 pages, the book follows their decade-long infatuation with each other, not shying away from explicit sex scenes, plenty of relationship conflict and emotional turmoil, and questions about the role of sexual identity and desire in the face of societal expectations — questions all too familiar to both current and older generations of men who love men in many other countries.

As a cultural product, no other publication may be as representative of the gay experience in China. Beijing Comrades was popularized online, turned into a movie in Taiwan, blocked from publication in China even in its safe-for-work version, and recently translated into English in cooperation with the anonymous author — though there is no authoritative version. Instead, the book speaks to the constant need for adaptation and change faced by the Chinese queer community, which will find spaces to survive no matter what.

— Katharin Tai

68. Red China Blues: My Long March from Mao to Now

Jan Wong (Doubleday Anchor Books, 1996)

Jan Wong’s memoir of China in the 1970s and ’80s is mostly forgotten outside of her native Canada, where she is more famous for a column dishing dirt on Toronto celebrities. But it presents a unique twist on the genre of books written by foreigners on sojourn in the Middle Kingdom. Red China Blues charts Wong’s first visit to China in 1972 as a student fired up by Maoist fervor, her attempts to learn Chinese while also hauling pig manure, her marriage to Norman Shulman, an American draft dodger, her disillusionment with the excesses of the Cultural Revolution, and then her eventual return to China as a foreign correspondent for the Globe and Mail. She arrived back in Beijing just in time to have a front row seat for the earth-shaking events of the summer of 1989. The book attempts to make sense of the political upheaval of the past half-century and her own connection to her ancestral homeland.

— Dylan Levi King

66. Last Quarter of the Moon

Chí Zijiàn 迟子建, translated by Bruce Humes (Harvill Secker, 2013)

Jiang Rong’s blockbuster Wolf Totem and Chi Zijian’s Last Quarter of the Moon were published within about a year of each other in the mid-2000s. Jiang’s book, a bloodthirsty prescription for national renewal that praised the nomadic Mongolian spirit, played fast and loose with the facts, and was attacked as “fascist,” went on to sell four million copies within a year. Chi’s haunting novel recording the past century of Evenki life in Inner Mongolia received a far more muted reception outside of literary circles, despite rendering a more intricate and evocative picture of nomadic life.

The author put in countless hours studying the Evenki, who now number in the tens of thousands and live mostly in the Evenki Autonomous Banner, close to where the Mongolian, Inner Mongolian, and Russian borders meet. The unnamed narrator, an elderly woman descended from tribal chieftains, describes the Evenki’s move from a nomadic life — herding reindeer across the steppes and hunting in the boreal forest — to settlement in permanent townships, and her own fight to stay connected to the mountains that she was raised in. Reindeer may not be as marketable as wolves, but Chi Zijian’s story is just as gripping as Jiang Rong’s, with none of his tiresome didacticism.

— Dylan Levi King

63. The Rose of Time: New and Selected Poems

Běi Dǎo 北岛, edited by Eliot Weinberger, with translations by Bonnie McDougall, David Hinton, and Eliot Weinberger (New Directions, 2010)

Bei Dao began writing poetry during the Cultural Revolution, founded the first unofficial literary journal in the People’s Republic of China in 1978, became one of the country’s best known poets in the ’80s, and then was in exile after the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989; he moved to Hong Kong in 2007 and has been allowed to travel in mainland China following a stroke in 2012, and remains one of the best known poets writing in Chinese today — and one of the leading lights of Chinese literature. The Rose of Time presents the most moving and innovative selections of his oeuvre up to 2010, from the “I — do — not — believe” of “The Answer” from the ’70s to his more recent “Black Map,” with the lines “I go home — reunions / are one less / fewer than goodbyes.” For an entryway either into Bei Dao’s own output over the last four decades or where contemporary Chinese poetry is, The Rose of Time is indispensable.

— Lucas Klein

59. The Corpse Walker: Real Life Stories, China From the Bottom Up

Liào Yìwǔ 廖亦武, translated by Wen Huang (Pantheon, 2008)

Many years before being branded a professional dissident, Liao Yiwu was a Chinese state-authorized poet. But his outspokenness over the Tiananmen student protests landed him in jail, and upon his release, he found himself abandoned by his wife, ostracized by acquaintances, and thrust into the bottom rungs of society. During this time, part of it wandering the streets of Chengdu, he compiled stories — via interviews — of China’s underclass, talking to a leper, a musician, a former Red Guard, a grave robber, a Falun Gong practitioner, and more. Sixty interviews were collected and published in Taiwan in 2001; 27 of those were translated for The Corpse Walker, which remains Liao’s representative English-language work.

Liao didn’t take notes while his subjects spoke, but he captures their voices and tries his best, where applicable, to preserve something of their human dignity. “I used to drive a human-waste truck,” a bathroom attendant says. “Nobody looked down on me because I was handling shit.” Liao himself is very much part of the dialogues, as when he tells a slick-talking human trafficker, “If I were the judge, I would first cut off your tongue as punishment.” The title story is about professional mourners who literally walk corpses from the world of the living into the world of the dead. “People in the countryside still believe that the fake money is used to bribe the corpse’s guardian ghosts so they don’t block the road to heaven,” Liao’s interviewee says, to which Liao quips: “So people used to think the world of the dead was equally corrupt.”

— Anthony Tao

56. Our Story: A Memoir of Love and Life in China

Ráo Píngrú 饶平如, translated by Nicky Harman (Pantheon, 2018)

Rao Pingru was 87 when he began to write the story of his life, focusing on his long marriage to his recently deceased wife, Meitang. In the absence of surviving photographs, he taught himself to paint, and so it is that Our Story is illustrated with his charming, quirky pictures.

Born in 1922, Rao received a Confucian education, and acquired an abiding love of classical Chinese poetry. As a young man, he fought in the anti-Japanese War (he paints the bloody battles vividly), escaping death by a whisker on several occasions. When peace came, his father arranged his marriage to Meitang. Rao gives us fascinating glimpses of the life they led in the late-40s and early-50s: their travels around China, local food specialities (illustrated in great detail), and his desperate attempts to find a job. Eventually, the couple settled in Shanghai, where he worked as an editor and they raised five children — before he was sent away to do reform through education during the Cultural Revolution. In the last part of the book, Rao describes in heartbreaking detail how he cared for Meitang as she battled diabetes and dementia, and mourned her death.

Rao became a TV celebrity when Our Story was first published in Chinese. He is now 97, and recently appeared at the Shanghai International Literary Festival.

— Nicky Harman

55. Ruined City

Jiǎ Píngwá 賈平娃, translated by Howard Goldblatt (University of Oklahoma Press, 2016)

Jia Pingwa’s Ruined City hit the Chinese literary scene like an atom bomb upon publication in 1993. The grim, funny portrait of literary bad boys was banned almost immediately, and remained officially out of print until 2009. Roasted by critics as pornographic and self-indulgent upon its release, the reputation of the novel only grew during the 16 years it circulated in samizdat editions and online bootlegs. Apart from being heralded as one of the finest novels of the past century, it was also credited as a sex-ed manual.

The novel’s anti-hero Zhuang Zhidie, a stand-in for Jia himself, scythes through the literary and political scene in Xijing, a thinly veiled version of Xi’an, tangling with rivals, having his palms greased by local bureaucrats, and still making time for dalliances with a lineup of adoring female fans. Ruined City is aggressively modern in its concerns, but borrows the forms of late Ming and early Qing vernacular novels. The dense prose of the original, full of classical allusions, as well as political jargon, makes Howard Goldblatt’s translation all the more impressive.

— Dylan Levi King

50. Notes of a Desolate Man

Chu T’ien-wen (朱天文 Zhū Tiānwén), translated by Howard Goldblatt and Sylvia Li-chun Lin (Columbia University Press, 1999)

Chu T’ien-wen, the daughter of Taiwanese literary luminary Chu Hsi-ning (朱西甯 Zhū Xīníng), got her start as a writer of maudlin romances on classical themes before breaking into the world of film, collaborating with Hou Hsiao-hsien (侯孝贤 Hóu Xiàoxián) and other auteurs of the New Wave cinema movement. Her work as a screenwriter, as well as the new political and cultural environment that came with the lifting of martial law in 1987, shook her loose from imperial Chinese nostalgia and drove her to create a new body of work that was focused on the unique experiences of urban Taiwanese.

Notes of a Desolate Man, published in 1994, tells the story of a gay man approaching middle age, who has flown from Taipei to Tokyo to care for a friend dying of AIDS. It’s a deeply sad, deeply passionate book that sprinkles its explorations of urban ennui, aging, sex, and the limits of radical politics with references to Lévi-Strauss, Fellini, Ozu, and classical poetry. This is among the finest records of middle age ever written, and a keen portrait of fin de siècle Taiwan.

— Dylan Levi King

46. Soul Mountain

Gāo Xíngjiàn 高行健, translated by Mabel Lee (Harper Perennial, 2000)

“What I want to say here is that literature can only be the voice of the individual and this has always been so,” Gao Xingjian said in his acceptance speech for the 2000 Nobel Prize. Gao’s voice is resounding in Soul Mountain, his most famous work, a part-autobiographical, part-fictional account of one man’s journey along the Yangtze River in search of the fabled mountain Lingshan. Gao, who became a French citizen in 1998, fled the oppressive political environment of Beijing in the 1980s to travel the remote mountains of Sichuan Province in southwest China. Soul Mountain was the result, a free-flowing, ecstatic, sometimes stream-of-consciousness novel that traces an unnamed protagonist’s physical and spiritual quest for inner peace and freedom. The novel is a rarity in the Chinese literary landscape, where studies of the human self are vastly outnumbered by plot-driven narratives.

— Bingxuan Wang

45. One Child: The Story of China’s Most Radical Experiment

Mei Fong (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016)

One Child follows the twists and turns of China’s most notorious social experiment: the planned birth policy instituted in 1980. Limiting families to a single offspring may have seemed prudent at the time, when China’s population was growing at alarming rates, but in reality, that decision carved out immense challenges for Chinese individuals as well as the world’s most populous country. For example, there’s Zhu Jianming, who had a reverse-sterilization operation just weeks after the death of his only child. His story illustrates the despair that accompanied the policy’s forced abortions and sterilizations. Yang Libing’s daughter was seized by family planning officials and placed on the global adoption market, a story that touches upon the corruption and human trafficking the policy fostered. And Liu Ting’s story is a harbinger of China’s future, when a generation will age out of the workforce amid a shrinking population. A former Wall Street Journal reporter out of Beijing, Mei Fong meticulously researched and documented these stories over the course of five years. One Child harkens back to an era that seems bygone — Chinese are now allowed two children — yet understanding the long-lasting effects of China’s social planning experiment is more important than before, as the country’s status grows ever larger on the global stage.

— Lenora Chu

41. Frontier

Cán Xuě 残雪, translated by Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping (Open Letter, 2017)

Can Xue prides herself on challenging readers with her experimental fiction, and challenge she does with Frontier, originally published in 2008 and translated in 2017. The novel is set in the mysterious Pebble Town, teeming with wildlife, where people make references to nearby Snow Mountain and a tropical garden in the sky. Each chapter focuses on the interactions between a few characters, drawing the reader into a beautiful and frightening world where everyone tries to figure out why they have come to work at the seemingly purposeless Design Institute and what their relationship is to one another. The reader remains in a haze as the events unfold, but the direct narration and compelling imagery is a powerful draw, immersing us in the strangeness and wide open sky.

— Lily Hartzell

33. Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang

Zhào Zǐyáng 赵紫阳, translated and edited by Bao Pu, Renee Chiang, Adi Ignatius (Simon and Schuster, 2009)

In 1987, it was possible to believe that the liberal reforms which had pulled China out of the Mao era would continue indefinitely. Zhao Ziyang was a big reason for that optimism: He was elevated to General Secretary of the Party that year, at the relatively young age of 68. But you probably know what happened next: Impatient with the speed of the reforms and upset at the proliferation of corruption, students took to the Beijing streets in April 1989, culminating in a bloody crackdown two months later that not only derailed China’s progressive course, but ruined a generation of the country’s best and brightest.

Zhao Ziyang was merely the most prominent of Tiananmen’s victims, spending the last 16 years of his life under house arrest. But that time wasn’t passed in complete silence: He secretly recorded his recollections in a set of tapes, 30 in total, each about an hour long, and had friends smuggle them out. Four years after his death, transcriptions of those tapes were published as the book Prisoner of the State, giving the public its first truly intimate look inside the highest echelons of the Chinese Communist Party.

In his journal, Zhao recounts, in agonizing detail, the battle within the walls of Zhongnanhai between himself and conservative rivals, and how tantalizingly close Zhao’s faction actually was to persuading Deng Xiaoping to pursue a different course of action…if only. If only, for instance, Zhao had not been called away for business in North Korea in late April; if only Li Peng hadn’t published a scathing People’s Daily editorial under Deng Xiaoping’s name while Zhao was gone; if only martial law had not been declared, which only invigorated the demonstrators; and so on. There is an alternative reality in which the Tiananmen protests are not violently suppressed, and China did not need to fill its moral vacuum with hard-hearted materialistic pursuit. We realize, reading Zhao’s memoir, how close we were to that reality — and in the process understand the possibility that people like him still lurk behind the opaque curtains of the central government. Even in death, Zhao remains a source for hope.

— Anthony Tao

30. Nine Continents: A Memoir In and Out of China

Xiǎolǔ Guō 郭小橹 (Grove Press, 2017)

Xiaolu Guo was introduced to Anglophone readers by Cindy Carter’s translation of Village Of Stone in 2005. It was impossible not to read the autobiographical novel of a girl escaping to the city without wanting to know more about the author’s own life. Guo returned to the autobiographical with her first novel written in English, A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary For Lovers, which was based on her own expatriation to London in 2002. Turning to memoir made perfect sense, but few Chinese writers, with the exception of old-guard heavyweights and those in exile, ever produce novel-length memoirs. That makes Guo’s Nine Continents even more special. She writes of her childhood, growing up in miserable poverty in a fishing village in the 1970s before escaping to follow her dreams at Beijing Film Academy, then in England, and her experience of motherhood and return from self-imposed exile. Guo’s story of overcoming her background to seek her dreams is — especially in China — not unique, but her perspective is one we are rarely given access to; and her talents as a writer make this an essential story of the Chinese experience.

— Dylan Levi King

28. China: Fragile Superpower: How China’s Internal Politics Could Derail Its Peaceful Rise

Susan Shirk (Oxford University Press, 2007)

As protest and conflict continue to rage in Hong Kong, Susan Shirk’s 12-year-old book about the fundamental insecurity of the Chinese government proves both eerily prescient and more relevant than ever. While Fragile Superpower, originally published in 2007, focused mainly on the frightening prospect of international conflict over other regional hotspots — her opening salvo, an imagined collision between U.S. and Chinese fighter jets in Taiwanese airspace and the messy aftermath, was all too vividly portrayed — Shirk’s takeaway message has unfortunately withstood the test of time: The Chinese government is more terrified of internal regime breakdown than external conflict.

In particular, her analysis of the dynamics of state-curated nationalism and the dangers it poses in terms of ultimately backing government actors into a corner is presented in a manner that is as accessible as it is foreboding. At the same time, subsequent events have proven less kind to some of her other conclusions; Shirk’s repeated entreaty that reason will prevail over raw emotion in responding to China’s many sins is less self-evident in an age of mass detentions in re-education camps. Nevertheless, adding to the sense of authority and immediacy to be found throughout the work is the fact that Fragile Superpower was written following Shirk’s stint as deputy assistant secretary of state for East Asia during the second Clinton administration, and draws directly on her firsthand experience working closely with Chinese officials. That makes this book a treasured staple of political science classes and general interest audiences alike, a rare work that seamlessly crosses the boundaries that ordinarily separate academic, journalistic, and political takes on otherwise well-trod ground. This invaluable message in a bottle is a timely and compelling reminder that the more things change in China, at its insecure core, the more the Party stays the same.

— Siodhbhra Parkin

24. The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao

Ian Johnson (Pantheon, 2017)

The Souls of China brings the reader face-to-face with the practitioners of a variety of spiritual traditions in China. Ian Johnson describes in vivid detail such experiences as Buddhist temple pilgrimages and festivals on the outskirts of Beijing, Daoist and folk religion practices in Shanxi Province, and the politics of protestant Christian house churches in Chengdu, Sichuan. Not all of religion and spirituality in China is covered here, but enough of it is, and the description and context given is so illuminating that the book, taken as a whole, communicates a compelling message about the direction of China’s national “soul” today. In short, although the lines of religion, spiritual practice, and “culture” are blurred — sometimes intentionally by the state — the Chinese people are responding to a genuine spiritual and moral vacuum created by many decades of state-led destruction and economic dislocation.

— Lucas Niewenhuis

22. The Last Days of Old Beijing: Life in the Vanishing Backstreets of a City Transformed

Michael Meyer (Walker & Company, 2008)

The Peace Corps program in China produced Peter Hessler, whose River Town and Oracle Bones are justly celebrated, but Michael Meyer’s three books of immersive reportage (The Last Days of Old Beijing, In Manchuria, and The Road to Sleeping Dragon) are equally worthy of acclaim. The Last Days of Old Beijing, Meyer’s first book, is a dispatch from a hutong near Dashilar in central Beijing, ground zero of the city’s aggressive transformation in the run-up to the 2008 Olympics. Meyer describes his life in his rented room and his job at a local school, but rather than being yet another solipsistic China memoir, The Last Days is refreshingly analytical and unsentimental, teasing out the political economy of the backstreets, reporting on the attempts at saving heritage buildings, and sketching the lives of his neighbors. Reading the book less than a decade on, it’s jarring to think that much of what he described is already gone.

— Dylan Levi King

20. The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom

John Pomfret (Henry Holt and Company, 2016)

Early in John Pomfret’s wildly ambitious 700-page masterpiece on the history of U.S.-China relations is an observation that sets the theme for the entire book: “If there is a pattern to this baffling complexity, it may be best described as a never-ending Buddhist cycle of reincarnation. Both sides experience rapturous enchantment begetting hope, followed by disappointment, repulsion, and disgust, only to return to fascination once again.” Indeed, many of the characters throughout the nearly 250 years of U.S.-China interaction can be found today, from the idealistic missionaries seeking to “change China” to the Chinese students with American educations who return to become their country’s political and business elite.

And that’s what makes The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom such a captivating read. Its thoroughly researched stories of riveting individuals throughout history put today’s U.S.-China relationship in much-needed context, particularly as that relationship falls under increased strain. Pomfret writes what is at its core a turbulent love story of two nations whose passions swing violently between desire and loathing. It’s a recipe for a dysfunctional relationship, but a relationship that defines our present and future — and one that makes for a fascinating book.

— Elliott Zaagman

15. Wealth and Power: China’s Long March to the Twenty-first Century

Orville Schell and John Delury (Random House, 2013)

Through lengthy historical profiles of 11 iconoclasts who changed China — all reformers or revolutionaries in one way or another — this wonderful book shows how China traveled the road from the Qing Dynasty to today, driven by the same quest for 富強 fùqiáng: wealth and power.

We are introduced at the start to Wei Yuan and Feng Guifen, two 19th-century scholars who pioneered the 自強 zìqiáng, or “self-strengthening school,” and warned of the growing gulf between China and the West. Then there are the reformers, Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao (as well as Zeng Guofan and Li Hongzhang), whose efforts were met with mixed responses from the Empress Dowager Cixi, the last ruler of the Qing. Next are Sun Yatsen, the 国服 guófú (or “father of the nation” — and its first president, if only for 45 days before military leader Yuan Shikai took over), and New Culture intellectual Chen Duxiu, who was integral to the May Fourth Movement during the early days of the Republic. More familiar figures then emerge, including Chiang Kai-shek, Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, Zhu Rongji — who oversaw China’s economic miracle in the 1990s and early 2000s — and Liu Xiaobo, who protested for political reform and was punished severely for it.

The individuals profiled are helpfully collated with chronologies, quotes, and multimedia resources at Asia Society’s “Wealth and Power Book Project,” which gives a clear and concise overview of a century and a half of China’s modern history and the visionaries who shaped it. China’s pursuit of power and prestige continues today with Xi Jinping, China’s latest reshaper, who would make for a fine epilogue in a new edition of Wealth and Power — a man whose legacy is open-ended but sure to create a lasting imprint on Chinese history.

— Alec Ash

14. In the Red: On Contemporary Chinese Culture

Geremie R. Barmé (Columbia University Press, 1999)

In the Red is arguably the best work of cultural criticism about post-Mao China. It comprises 12 interweaving essays that present a wide-ranging history of urban Chinese culture in the first two decades of the reform era. Sinologist Geremie Barmé, who was personal friends (or frenemies) with most of the key figures in this story, explores both how Beijing constructed a “velvet prison” to beguile intellectuals into self-censorship, and how artists, scholars, and writers approached their work under an increasingly marketized authoritarianism. Some suffered for their ideals, others profited from “packaged dissent,” still more lent their services to marketing a regime in desperate search of a meaning. The book is consistently engaging and provocative, as Barmé’s striking prose exemplifies the possibilities for sophisticated analysis without the obtuse academic jargon and somniferous theoretical excursions that asphyxiate much cultural scholarship. Present-day readers — perhaps those perusing the work on their iPhones or Kindles — will notice that the internet had not conquered China by 1999, but Barmé’s incisive observations remain enormously insightful for understanding Chinese cultural politics.

— Neil Thomas

12. Oracle Bones: A Journey Through Time in China

Peter Hessler (Harper, 2006)

In 2002, Peter Hessler followed up River Town, his account of teaching young people in Fuling in the late 1990s, with a book that delves deeper into greater contemporary China. He starts at both ends, as it were; he goes right back to the oracle bones of the book’s title, the system of divination that dates back more than 3,000 years, and then interpolates history with descriptions of how his former college students have progressed since graduation, and interviews numerous other ordinary people whom he meets as he travels around China. Reviewers have commented that the format is over-ambitious, that inevitably in a single book, Hessler can only touch on limited aspects of China’s history, culture, and contemporary development, and that his choices are “random.” But what almost all readers agree on is that he has a beguiling ability to relate to ordinary folk and relate their lives. It is interesting to note that his style of longform journalism has attracted a great deal of admiration in China. In the words of one writer, “Chinese people worship Hessler,” and many of his books have been translated into Chinese.

— Nicky Harman

11. Out of Mao’s Shadow: The Struggle for the Soul of a New China

Philip P. Pan (Simon & Schuster, 2008)

Out of Mao’s Shadow is a tribute to survivors: the Chinese who persevered through famine, revolution, shattered idealism, and the inversion of values systems. It is a profile of the Chinese national character, of brave men and women whose struggles exemplify the enduring human spirit. Philip Pan, who reported for the Washington Post for eight years in Beijing, interviews lawyers, activists, doctors, officials, and everyday people, and tells on-the-ground stories about SARS, censorship, politicians, martyrs, and more. Two profiles in particular stand out: The first is on Hu Jie, a man obsessed with Lin Zhao, a girl imprisoned during the Cultural Revolution who legend has it wrote on the walls with her own blood; the other is on Chen Guangcheng, a blind lawyer harassed by authorities and goons in his rural village. (Chen would capture international headlines years later when he escaped house arrest, turned up at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, and was eventually granted permission — after high-level negotiations — to leave for the U.S.)

It’s hard to read Out of Mao’s Shadow and not come away marveling at the Chinese people and thinking that the state could benefit from celebrating its most colorful and intrepid characters. Alas, reading this book 11 years later, it’s perhaps more appropriate to wonder who will continue to take up the struggle as the void left by Mao’s death becomes increasingly filled with money and power. How much soul is left to struggle for?

— Anthony Tao

10. Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China

Leslie T. Chang (Spiegel & Grau, 2007)

I can’t tell you how many times people have mistaken me, a former factory girl who wrote a memoir about my experience (No. TK on this list), for Leslie Chang, the author of Factory Girls. I always say I’m flattered, but I have to disappoint them. It so happens that Factory Girls is one of my favorite books about contemporary China.

A former correspondent for the Wall Street Journal, Chang is brilliant in providing social and economic context, but Factory Girls goes much deeper. Her book is an intimate and powerful portrait of young migrant workers in Dongguan, a giant manufacturing base in southern China’s Pearl River Delta, where women account for 70 percent of the labor force. The city is “a perverse expression of China at its most extreme,” as Chang writes. The girls in Dongguan leave their home villages to venture out to the city because “there’s nothing to do at home.” They fill out the production lines in one of hundreds of factories. In the feverish and chaotic city, they switch friends as frequently as they change jobs. They go to night schools to better themselves as slogans tell them that “to die poor is a sin.” These factory girls are really the unsung heroes of China’s economic miracle.

— Lijia Zhang

Jump to: 100-81 | 80-61 | 60-41 | 40-21 | 20-1 | List view

9. Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China

Evan Osnos (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014)

Age of Ambition is itself an ambitious book, aiming to capture the essence of contemporary China through a diverse set of people that Evan Osnos met during his eight years in the country, where he was a staff writer for the New Yorker. What Osnos achieves is a compelling series of snapshots of 21st-century China, threaded together by each character’s burning desire to change their fortunes. Part of this book’s achievement is its treatment — with equal respect — of outliers such as Ai Weiwei and ordinary people like internet entrepreneur Gong Haiyan. After all, they all have something valuable to say, and are all part of the “real China” story. In one particularly entertaining vignette, Osnos joins a Chinese tour group on a holiday to Europe; for him, the explorers are absurd, but also poignant and proud. You’ll find yourself laughing with them, and cheering them on as they pursue their grand, sometimes quixotic ambitions.

— Amy Hawkins

Jump to: 100-81 | 80-61 | 60-41 | 40-21 | 20-1 | List view

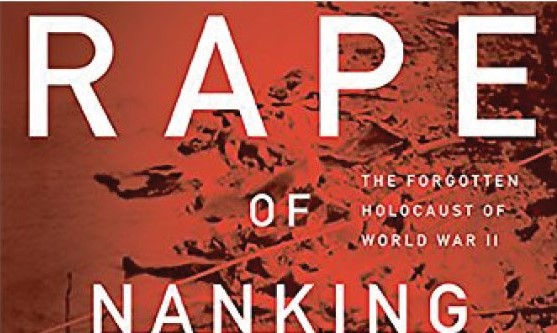

8. The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II

Iris Chang (Basic Books, 1997)

Hailed after her suicide as one of the last victims of the Nanjing Massacre, Iris Chang’s memorial sits among those brutally killed in the weeks following the city’s capture. The Rape of Nanking propelled what Chang termed “the forgotten holocaust” back into the public consciousness, leading in turn to death threats from Japanese ultra-nationalists amid an 18-month book tour. The book is a searing exploration of the nature of humanity and that “thin veneer of civilization” which, once stripped, led the Japanese Imperial Army in Nanjing to kill more civilians in six weeks than the initial death tolls of Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined.

Given Chang’s mission to give a voice to the (politically convenient) silence of its victims, The Rape of Nanking assumes no prior knowledge of readers. While pilloried by less-renowned historians for her lack of academic rigor, Chang was responsible for uncovering multiple primary sources, including the meticulously thorough diaries of two prominent defenders of the international safety zone, credited for saving the lives of at least 200,000 civilians. In examining the massacre through the various lenses of perpetrator, victim, and finally international observer, Chang tasks readers to draw their own conclusions regarding the heavily disputed events of 1937-38, putting in context the complicity of foreign governments to whom the subject was inconvenient, East Asia scholars who considered it taboo, and the ongoing outrage at continued reticence of Japanese officials to acknowledge and atone for the sadistic rape, torture, and murder of half of Nanjing’s population.

— Nell Greenhouse

Jump to: 100-81 | 80-61 | 60-41 | 40-21 | 20-1 | List view

7. Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768

Philip Kuhn (Harvard University Press, 1990)

Much as a good paleontologist can do with a single fossilized dinosaur bone, a gifted historian can take a single historical episode from a given time period and paint a vivid and accurate picture of the whole. This is precisely what the late Philip Kuhn, who died in 2016, did with his second book, Soulstealers. Focusing on the Qing imperial administration’s reaction to a rash of allegations of witchcraft (practitioners of which were said to be snipping off the braids of victims and stealing their souls), and drawing on extensive archival research, Kuhn deftly captured the essence of the imperial bureaucracy and the nature of political control during the Qianlong reign, while also shedding light on the lives of ordinary people across a range of social strata. And it reminds us that even back in 1768, some Chinese were already cutting queues.

— Kaiser Kuo

Jump to: 100-81 | 80-61 | 60-41 | 40-21 | 20-1 | List view

6. The Good Earth

Pearl S. Buck (John Day, 1931)

The Good Earth is a sweeping novel in the tradition of English literary realism, but at its core is unmistakably Chinese. At her acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1938, titled “The Chinese Novel,” Pearl S. Buck praised the Chinese novelist as a writer for the people: “His place is in the street. He is happiest there.” She concluded, “He must be satisfied if the common people hear him gladly. At least, so I have been taught in China.”

She was well taught. For the first half of her life, Buck felt more at home in China than anywhere else. She learned classical Chinese at an early age, attended school in Shanghai, and moved to Anhui Province soon after her first marriage, an experience that depressed her but provided the basis for The Good Earth, which was published in 1931 to critical acclaim and commercial success. The novel begins with Wang Lung’s marriage to O-lan, hardscrabble characters who form the story’s backbone. They persevere through hardship and war brought about by the fall of the Qing Dynasty, experience fortune and joy and scandal, desire like sickness, and devotion that might as well be called love. They break our hearts with the way they fight against the forces of life, and through it all, there is no question that they reside in the proverbial street, surviving off a land that any Chinese novelist would be proud to claim as their own.

— Anthony Tao

Jump to: 100-81 | 80-61 | 60-41 | 40-21 | 20-1 | List view

5. The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers

Richard McGregor (Harper, 2010)

One evening in Beijing in the late 1990s, Rupert Murdoch quipped to fellow dinner guests that he had yet to meet any Communists during his trips to China. The modern rulers of the Middle Kingdom might not be the Marxist ideologues Murdoch imagined, but they operate very much like the Communists of old: behind an opaque screen, with a hard grip over the military and state apparatus.

One of the guests at Murdoch’s dinner was the veteran journalist Richard McGregor. In The Party, he draws from years of reporting and scholarly analysis to pierce through the red fog and shed light on the Chinese Communist Party, a deeply powerful yet often misunderstood organization. Ambitious in scope and rich in detail, the book offers an acute dissection and vivid accounting of the Party’s roles, how it operates, and the reasons behind its longevity. Published in 2010, The Party predated the reign of Xi Jinping, but as the current Chinese leader expands and tightens the Party’s control over all sectors of society, the book feels particularly timely, even prescient. By reading it, one understands that the Party is always the big boss, deriving its authority not from any one individual at the helm, but an expansive system — one that creates and enables power-brokers and abusers of that same power.

— Yangyang Cheng

Jump to: 100-81 | 80-61 | 60-41 | 40-21 | 20-1 | List view

4. The Real Story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China: The Complete Fiction of Lu Xun

Lǔ Xùn 鲁迅 (pen name of Zhōu Shùrén 周树人), translated by Julia Lovell (Penguin Classics, 2010)

This is an essential collection of work from China’s greatest 20th-century writer, expertly translated by Julia Lovell.

In his 1921 satirical novella The Real Story of Ah-Q, Lu Xun captures the opportunism, anti-intellectualism, and narcissism of late-Qing, early-Republican China. From the village of Weizhuang, the educated, jobless Ah Q recoils at his oppressors — those who are above him in the hierarchy — but bullies those who are below him. He confronts humiliations with self-deception, convincing himself of his “spiritual victories.” One of the most famous scenes is at the opening: After Ah Q brags about being from the same clan as one Mr. Zhao (赵太爷), he is summoned by a tyrant who slaps him in the face: ‘How could you be named Zhao! Do you think you are worthy of the name Zhao?” Ah Q is often seen as a symbol of the shortcomings of China’s national character — even today. On the internet, dissidents often refer to China’s dignitaries as from the “Zhao family,” whose self-interests are defended by voiceless, amnesiac Ah Q’s who have convinced themselves that they belong to the clan.

Also included in this collection is the famous short story “A Madman’s Diary.” Not to be confused with Nikolai Gogol’s “Diary of a Madman,” Lu Xun’s madman slowly realizes that the villagers around him — his neighbors, doctor, and even his brother — are cannibals who are coming after him. He implores in the end, “Save the children…” As the very first modern work published in vernacular Chinese, this 1918 story became the centerpiece for China’s New Culture Movement, during which intellectuals critically reassessed traditional Chinese culture and began rejecting its cultural norms.

— Tianyu M. Fang

3. China Pop: How Soap Operas, Tabloids and Bestsellers Are Transforming a Culture

Jianying Zha (The New Press, 1995)

Published six years after the Tiananmen massacre, China Pop’s opening page sees Jianying Zha making a bold and refreshing request for readers to consider China outside the shadow of June 4, 1989. The proposition is all the more powerful because so very few people are able to write as authentically and piercingly on that subject. An example from the book:

We are the golden children who went astray, the delicious promise that turned sour, the little angels who somehow grew horns on our heads. Our lesson about history is that it should never be repeated. It’s an important lesson to keep in mind — but how can we reasonably expect others to carry this burden or feel the same way about our past? After all, hadn’t we bitterly resented our parents for clinging to their own history? Our younger siblings have little recollection of the Cultural Revolution. Our children will have no memory of Tiananmen. They may read about these events in the history books, see them in films, hear stories about them at dinner tables. So we hope. But they probably won’t share our intensity about them. They will have a lightness of spirit about life that doesn’t come naturally to us. Or so we hope.

Zha’s gifts as a witness and writer are to be envied; in China Pop, she repeatedly exercises her special ability to tap into the country’s collective conscience without resorting to armchair psychoanalysis or excuse-making. The book feels uniquely hers: It is filled with pop culture references and Chinese proverbs (“If the fish likes what’s on the hook, well then, fishing is fair play”), interviews with film directors and authors — Chen Kaige, Jia Pingwa, Chan Koonchung, Wang Shuo, etc. — rock stars and intellectuals, and observations about transformation and loss, Hong Kong and cassettes (“Red Sun, an adaption of famous old hymns praising Mao to soft rock rhythms with electronic synthesizers”), McDonald’s and porn. China Pop is an unvarnished document of an era, filled with evocative and wry reflections on a generation of Chinese I wish we could hear more from. They speak loudly in this book, and memorably.

— Anthony Tao

The China Project Book List. Back to main Books List page