The China Project Book List — sort by genre: History

Sort by genre:

Culture/Society/Memoir | Literature | History | Politics | Business/Tech

Sort by time period of primary subject matter:

Ancient and Imperial China | Republican Era to 1949 | Mao to Tiananmen | 1990s to Pre-Olympics | 2008-Present

~

84. Cinderella’s Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding

Dorothy Ko (University of California Press, 2007)

A self-proclaimed “alternative history” of the practice of footbinding in China, Cinderella’s Sisters is a gratifyingly challenging book. The premise is straightforward, if somewhat provocative: The dominant narrative of footbinding as a painful patriarchal practice imposed upon women for the pleasure of men is an ahistorical oversimplification — and one that serves to obscure the voices and experiences of the women at the heart of the story. In her complex book, which simultaneously serves as a social history, literary criticism, and study of material culture, Dorothy Ko seeks to “unwrap” footbinding in an effort to reveal the desires, motivations, and lived experiences of the women themselves who endured and to an extent drove the practice for the thousand or so years it persisted. While Ko, who teaches history at Barnard College, is careful to never fully condone or condemn footbinding, and does not shy from the unpleasant — and, as many would persuasively argue, brutal — realities of the practice, she does emphasize that for many Chinese women, bound feet were integral to their perceptions of dignity and self-worth. In this vein, Ko explores how different styles of footbinding emerged and flourished at different periods and locations, locating the various methods of breaking, bending, and binding the female foot within the more conventional history of Chinese fashion. Drawing on an array of sources, Ko thus convincingly seeks to dispel the perception of footbinding as a practice uniformly and unidirectionally inflicted upon women by men, and instead weaves a more complex tale that allows for an “open-ended space,” to use Ko’s phrase, in which the resilient voices of those whose feet were bound might finally find an audience.

— Siodhbhra Parkin

79. The Man Awakened from Dreams: One Man’s Life in a North China Village, 1857-1942

Henrietta Harrison (Stanford University Press, 2005)

In this beautifully written work of local and personal history, author Henrietta Harrison provides a gentle yet compelling corrective to the tendency for books about China to focus on individuals and ideas with outsize impact. As she writes in the preface to this fascinating account about an ordinary man living an ordinary life in a tiny village in Shanxi Province, “Real humanity in historical accounts is all too often restricted to great leaders, famous writers, or original thinkers.” Without a trace of irony, she notes of the eponymous main character of her book: “Liu Dapeng was none of these.” Using the 400 or so volumes of personal diaries Liu left behind, Harrison paints a deeply human portrait of Liu and his family as they struggle to cope with the massive changes that gripped China in the late-19th and early-20th century. At the same time, Harrison artfully demonstrates how seemingly abstract developments such as the gradual shift away from Confucian ideology had immediate and deeply felt personal impacts. The Man Awakened from Dreams is therefore an important reminder that when it comes to a country as vast and complex as China, the best stories that teach us the most are not always the ones taken straight from the headlines.

— Siodhbhra Parkin

76. Imperial China 900–1800

F.W. Mote (Harvard University Press, 1999)

When it comes to English-language books on China, F. W. Mote’s Imperial China is as magisterial as it gets, taking on a broad canvas with confident strokes. Mote, who first went to China during World War II with the Office of Strategic Services (the CIA’s precursor), packs 40 years of scholarship into his work. By starting at the fall of the Tang and running through the high Qing, Imperial China has room to delve deeper than other general histories that aim for “5,000 years.” Mote makes the most of this decision, delivering narratives compelling enough to prompt frequent Wikipedia dives into his well-drawn characters, like standouts Liao Emperor Abaoji and reformist councilor Wang Anshi.

At its core, Imperial China is political history. Mote takes emperors and eunuchs to task for their failings, unafraid to judge leading characters for their decisions without undue deference to received historical tradition. He then makes his history relevant by grappling with challenges of governance applicable across ages. The book is particularly strong in two aspects: information on steppe peoples and elite political philosophy. It perhaps works best as a capstone for a 101 learner, bridging knowledge across dynasties and inspiring curiosity for deeper reading.

— Jordan Schneider

73. Public Passions: The Trial of Shi Jianqiao and the Rise of Popular Sympathy in Republican China

Eugenia Lean (University of California Press, 2007)

In the fall of 1925, a warlord named Shi Congbing was decapitated by his rival. His head stuck was stuck on a pole outside a train station. Ten years later, Shi’s daughter — Shi Jianqiao — tracked down her father’s murderer to a temple, where he was leading a sutra-chanting group. She dumped three rounds from a Browning semi-automatic into the back of his head, splattering his brains all over his prayer circle.

Eugenia Lean gives a fine account of the gory details, the media circus, and the legal wranglings that followed, but her purpose is teasing out something about the sociopolitical character of the Republican Era. Lean uses the Shi Jianqiao case to illustrate a new “popular sympathy” (tóngqíng 同情) in the Republican Era, when a new urban audience was able to follow updates in the case almost as they happened. One of the first trials by media, an unruly debate took place between those upholding rule of law (murder is illegal) and more ancient ethics (avenging your father’s murder is justified). We won’t give away the ending, but just know that Shi Jianqiao — whose spirit is revived in Lean’s book — went down in history as a bad-ass heroine.

— Dylan Levi King

72. Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China

Angus C. Graham (Open Court, 1989)

Disputers of the Tao is a marvelously sophisticated survey of the major streams of thought of pre-Qin China, how they emerge in response to the social-political environment and how they are in constant interaction with each other over time. As the title suggests, Graham reminds us that the notion of “Tao” was not particular to Taoists, but that each school of thought was working out its own Way. That is what they disputed: how should Tao be understood and practiced. The book is an excellent introduction to the differences between Confucius and Mozi and the Yangists and others. It clearly draws out distinctions between Confucius and Mencius and Xunzi. The Sophists and Zhuangzi are expertly analyzed. And it is fairly persuasive on a point that not everyone will accept: the nonexistence of a historical person, Laozi, the credited founder of Taoism. Surveys of this sort are difficult to pull off well without lapsing into textbook simplicity, but this one succeeds in both introducing basic concepts and also drilling deeply into fascinating philosophical, historical, and linguistic debates.

— Sam Crane

60. Mao’s China and After: A History of the People’s Republic, Third Edition

Maurice Meisner (Free Press, 1999)

If there is a reason why the late Maurice Meisner’s Mao’s China, originally published in 1977 and now in its revised third edition (Mao’s China and After, 1999), was and is still widely assigned in history and political science courses on China, it is that Meisner maintains an evenhanded and dispassionate stance when tackling episodes and personages in PRC history that tend to excite passions. Meisner’s command of detail and knowledge of the arcana of the Communist Party bureaucracy doesn’t interfere with his ability to identify what really matters, and his personal politics — he was a lifelong leftist — don’t soften the blows when he delivers them.

— Kaiser Kuo

58. Mao’s Last Revolution

Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals (Harvard University Press, 2006)

This is the book to recommend whenever you come across someone tossing out comparisons between the Cultural Revolution and present-day political campaigns, internecine Twitter battles, or campus free speech wars. Mao’s Last Revolution is the book on the Cultural Revolution, and it manages to overturn both the official Communist Party narrative of bad elements co-opting the campaign as well as received wisdom in the West, which has Mao and a couple of buddies leading a campaign against their foes. MacFarquhar and Schoenhals’ weighty tome is sharply written and draws on documents and sources previously unavailable to scholars. Mao’s Last Revolution reveals the extent of the chaos between 1966 and 1976, with top leaders turning on each other, factions within the Party rising and falling, a near-civil war that saw the People’s Liberal Army clashing with youth militias, “revolutionary masses” fiddling with nuclear weapons, and sustained violence that continued even after the arrest of the Gang of Four.

— Dylan Levi King

54. The Chinese Enlightenment: Intellectuals and the Legacy of the May Fourth Movement of 1919

Vera Schwarcz (University of California Press, 1986)

No period is more crucial to the understanding of modern Chinese intellectual history than the May Fourth Movement, centering on the protests of 1919 but also describing the five or so years preceding and following that event. In this scholarly book, Vera Schwarcz examines the tension at the heart of the movement: between the exigencies of national salvation (救国 jiùguó) and enlightenment (启蒙 qǐméng), between nationalism and cultural iconoclasm. How, she asks, did thinkers of the May Fourth period reconcile the urgent need they felt to save the nation — from warlords, from imperialist aggressors — with the view so many of them shared that it was China’s very traditionalism, its national essence, that was at the root of its problems?

— Kaiser Kuo

48. Banished Immortal

Hā Jīn 哈金 (pen name of Jīn Xuěfēi 金雪飞) (Deckle Edge, 2019)

Ha Jin’s The Banished Immortal is in a category all its own, uniquely illuminating on its subject, Lǐ Bái 李白 and his poetry, but Chinese poetry more generally and life in the Tang Dynasty too. Relying on original sources, including contemporary accounts, Ha Jin makes Li Bai come alive in all his ambition and restlessness, warmth, egocentrism, and dissipation — a flawed and complicated man who composed some of the most divine poetry ever written.

Before reading The Banished Immortal, I had never understood just how special and heartbreaking was Li Bai’s relationship with Dù Fǔ 杜甫 — considered alongside Li Bai as one of China’s greatest poets — or comprehended the desperate lengths Li Bai went in his quest for an appointment to the imperial court. It’s fascinating to read about how he frequently sabotaged his chances through egotistical posturing around the people whose help he craved. The Banished Immortal is a nuanced portrait of a complex man and his relationships with his wives, friends, fans, and the world around him more broadly. If Ha Jin exposes Li Bai’s flaws, he never diminishes his genius; his translations and commentaries on the poetry alone make this book a treasure.

— Linda Jaivin

43. Nixon and Mao: The Week That Changed the World

Margaret MacMillan (Penguin, 2006)

Richard Nixon sat with an ailing Mao Zedong for only one hour on February 21, 1972, neither man saying anything surprising or interesting. But that meeting was a “geopolitical earthquake,” according to Winston Lord (then an aide to Henry Kissinger), and the following seven days, when Nixon visited three Chinese cities, may well have been “the week that changed the world” (Nixon’s words). Margaret MacMillan brings all this to life in Nixon and Mao, deploying biographical sketches and rich anecdotes against the backdrop of Chinese history, the Cold War, America’s relationship with its Asian allies, and Vietnam. She notes that while the time was ripe for the U.S. and China to come together, both sides took significant risks to make it happen. “Asia will be at the center of the world again,” MacMillan writes. “Yet there will be no peace for Asia or for the world unless those two great Pacific powers, the United States and China, the one supreme today and the other perhaps tomorrow, find ways to work with each other. To understand their relationship we need to go back to 1972, to the moment when it started anew.”

— Anthony Tao

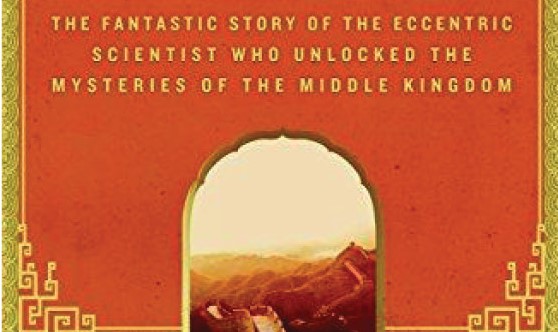

37. The Man Who Loved China: The Fantastic Story of the Eccentric Scientist Who Unlocked the Mysteries of the Middle Kingdom

Simon Winchester (Harper, 2008)

The “man who loved China” is Joseph Needham, an eccentric young biologist — and adventurer, nudist, accordionist, chain-smoker, etc. — who arrived in Chongqing during the Second World War and was instantly entranced. He spent the next decade producing what would become a 15,000-page, 24-volume encyclopedia called Science and Civilisation in China, an authoritative account of a country no Westerner had ever known with such depth or clarity. As author Simon Winchester giddily relays, “Needham slowly and steadily managed to replace the dismissive ignorance with which China had long been viewed — to amend it first to a widespread sympathetic understanding and then, as time went on, to have most of the western world view China as the wiser western nations do today, with a sense of respect, amazement, and awe. And awe, as fate would have it, was in time directed at him as well.” The Man Who Loved China is a delightful read about a distinguished scientist whose manic energy leaps off the pages.

— Anthony Tao

29. Forgotten Ally: China’s World War II, 1937-1945

Rana Mitter (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013)

Rana Mitter’s book on China during the Second World War looks not just at the Communists in Yan’an or the Nationalists in Nanjing and their wartime capital of Chongqing: He also takes an unblinking look at the puppet regime of Wang Jingwei 汪精衞, who capitulated to the Japanese in 1937. The book makes use of many newly available sources, including the diary of Zhou Fohai 周佛海, who served at various points under all three regimes, as one of the founders of the CCP in 1921, a member of the Kuomintang after 1924, and finally, at the “peak” of his career, second in command under Wang Jingwei. Chiang Kai-shek, often portrayed as a sniveling villain in the Chinese propaganda of an earlier time, and as venal, vain, corrupt and incompetent in the account burned into the American consciousness by Barbara Tuchman’s Stillwell and the American Experience in China, emerges in this telling as a much more complex and conflicted character.

— Kaiser Kuo

23. The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams and the Making of Modern China

Julia Lovell (Picador USA, 2011)

Utilizing extensive contemporary accounts and letters from participants, including the Emperor and British foot soldiers, Julia Lovell is able to capture the quasi-surreal “tragicomedy” of intransigence, self-deception, and slaughter that was the First Opium War. “Two and a half years after this war had started,” she writes, “[Chinese Emperor] Daoguang found himself still lacking the most basic information about his antagonists: Where in fact…is England?…How is it they have a 22-year-old woman for a queen? Is she married?” In the second half of the book, Lovell shows how the war, in many ways of little consequence at the time, would be used by Britain and U.S. for the next 150 years. Released in 2011, the sections about contemporary China read a bit dated, as 10 years ago feels nearly as foreign as the 1840s; still, the book is a compelling, comprehensive account of the war itself, and the war in the public consciousness that rages at all times across the world.

— Gabriel Clermont

20. The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom

John Pomfret (Henry Holt and Company, 2016)

Early in John Pomfret’s wildly ambitious 700-page masterpiece on the history of U.S.-China relations is an observation that sets the theme for the entire book: “If there is a pattern to this baffling complexity, it may be best described as a never-ending Buddhist cycle of reincarnation. Both sides experience rapturous enchantment begetting hope, followed by disappointment, repulsion, and disgust, only to return to fascination once again.” Indeed, many of the characters throughout the nearly 250 years of U.S.-China interaction can be found today, from the idealistic missionaries seeking to “change China” to the Chinese students with American educations who return to become their country’s political and business elite.

And that’s what makes The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom such a captivating read. Its thoroughly researched stories of riveting individuals throughout history put today’s U.S.-China relationship in much-needed context, particularly as that relationship falls under increased strain. Pomfret writes what is at its core a turbulent love story of two nations whose passions swing violently between desire and loathing. It’s a recipe for a dysfunctional relationship, but a relationship that defines our present and future — and one that makes for a fascinating book.

— Elliott Zaagman

18. 1587: A Year of No Significance

Ray Huang (Yale University Press, 1982)

If you’ve ever been in a museum in China and found yourself bored to tears by the endless displays of various earls and emperors’ furniture, robes, and other regalia, then here is a book for you. For in 1587, you will learn the truth about the late Ming Dynasty, which is that life in the imperial court was just as boring for the people who lived through it as it seems to us today. In Ray Huang’s telling, the Ming government was a doomed mess of foible and failure, like a 16th-century Veep. He describes the pomp and grandeur and pointless ceremony of imperial business with a kind of submerged dry wit: “The daily audience with the court, for instance, was loathed even by the most diligent statesmen.” But his thesis is a serious one: Ming society had become so paralyzed by elaborate rules, rituals, and moral constraints that it stifled whatever power any individual — even the Wanli emperor himself — could exert to arrest its decline. It’s a sad, sobering look at how things started going wrong for China all those centuries ago, especially at a time when the country’s current leaders have their own ideas about how to put things right.

— Ray Zhong

16. The Boxer Rebellion: The Dramatic Story of China’s War on Foreigners that Shook the World in the Summer of 1900

Diana Preston (Walker Books, 2000)

The Boxers — so-called because foreigners associated their brand of ritualistic calisthenics with pugilists — were impoverished and dispossessed northerners who launched an initially obscure peasant movement that turned murderous, with Western missionaries and Chinese Christians bearing the brunt of their attacks: “hacked to pieces, skinned alive, set alight, or buried still living,” Diana Preston writes. But The Boxer Rebellion is more than an accounting of atrocity: it explains the how and why of the conflict in the context of global colonialism at the end of the “British Century,” of Darwinism and scientific revolt, of a world on the brink of all-out war, the rising militarism of Japan, the legacy of Empress Dowager Cixi, and the waning days of the Qing Dynasty. And what was all the bloodshed for? This is perhaps the most sobering lesson of it all: the Boxer Rebellion merely presaged more senseless fighting to come, in Europe, on a much greater scale.

— Anthony Tao

14. In the Red: On Contemporary Chinese Culture

Geremie R. Barmé (Columbia University Press, 1999)

In the Red is arguably the best work of cultural criticism about post-Mao China. It comprises 12 interweaving essays that present a wide-ranging history of urban Chinese culture in the first two decades of the reform era. Sinologist Geremie Barmé, who was personal friends (or frenemies) with most of the key figures in this story, explores both how Beijing constructed a “velvet prison” to beguile intellectuals into self-censorship, and how artists, scholars, and writers approached their work under an increasingly marketized authoritarianism. Some suffered for their ideals, others profited from “packaged dissent,” still more lent their services to marketing a regime in desperate search of a meaning. The book is consistently engaging and provocative, as Barmé’s striking prose exemplifies the possibilities for sophisticated analysis without the obtuse academic jargon and somniferous theoretical excursions that asphyxiate much cultural scholarship. Present-day readers — perhaps those perusing the work on their iPhones or Kindles — will notice that the internet had not conquered China by 1999, but Barmé’s incisive observations remain enormously insightful for understanding Chinese cultural politics.

— Neil Thomas

13. Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War

Stephen Platt (Vintage 2012)

The author of this stand-out book argues convincingly that the “Taiping Civil War” would be a better name for the bloody conflagration best known as the Taiping Rebellion. That war pitted a quasi-Christian sect against the Qing Empire from 1851 to 1863, during much of which the Taipings ruled from the old Ming capital of Nanjing. In this richly detailed and beautifully-written telling, Stephen Platt focuses on the careers of two individuals on opposing sides of the conflict. On the Taiping side, there is Hong Rengan, cousin of Taiping founder and “God’s Chinese son” Hong Xiuquan. Hong Rengan, who would become the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom’s “Shield King,” was steeped in Christian theology as the assistant to a British missionary and worked hard to win the support of British and other Western powers to the Taiping side — and nearly did. On the dynastic side of the fight, Platt presents Zeng Guofan, an eminent Han scholar-official who, despite what any 21st century reader might casually diagnose as depression and anxiety, leads Qing forces to narrow victory. A profoundly important book about one of the most consequential conflicts in human history, which claimed a staggering 20 million lives.

— Kaiser Kuo

8. The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II

Iris Chang (Basic Books, 1997)

Hailed after her suicide as one of the last victims of the Nanjing Massacre, Iris Chang’s memorial sits among those brutally killed in the weeks following the city’s capture. The Rape of Nanking propelled what Chang termed “the forgotten holocaust” back into the public consciousness, leading in turn to death threats from Japanese ultra-nationalists amid an 18-month book tour. The book is a searing exploration of the nature of humanity and that “thin veneer of civilization” which, once stripped, led the Japanese Imperial Army in Nanjing to kill more civilians in six weeks than the initial death tolls of Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined.

Given Chang’s mission to give a voice to the (politically convenient) silence of its victims, The Rape of Nanking assumes no prior knowledge of readers. While pilloried by less-renowned historians for her lack of academic rigor, Chang was responsible for uncovering multiple primary sources, including the meticulously thorough diaries of two prominent defenders of the international safety zone, credited for saving the lives of at least 200,000 civilians. In examining the massacre through the various lenses of perpetrator, victim, and finally international observer, Chang tasks readers to draw their own conclusions regarding the heavily disputed events of 1937-38, putting in context the complicity of foreign governments to whom the subject was inconvenient, East Asia scholars who considered it taboo, and the ongoing outrage at continued reticence of Japanese officials to acknowledge and atone for the sadistic rape, torture, and murder of half of Nanjing’s population.

— Nell Greenhouse

7. Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768

Philip Kuhn (Harvard University Press, 1990)

Much as a good paleontologist can do with a single fossilized dinosaur bone, a gifted historian can take a single historical episode from a given time period and paint a vivid and accurate picture of the whole. This is precisely what the late Philip Kuhn, who died in 2016, did with his second book, Soulstealers. Focusing on the Qing imperial administration’s reaction to a rash of allegations of witchcraft (practitioners of which were said to be snipping off the braids of victims and stealing their souls), and drawing on extensive archival research, Kuhn deftly captured the essence of the imperial bureaucracy and the nature of political control during the Qianlong reign, while also shedding light on the lives of ordinary people across a range of social strata. And it reminds us that even back in 1768, some Chinese were already cutting queues.

— Kaiser Kuo

2. The Search for Modern China

Jonathan Spence (W. W. Norton & Company, 1990)

This classic, first published in 1990 but with second and third editions published in 1999 and 2013, remains the go-to single-volume history book covering China from the end of the Ming through the Reform Era. Aimed at general readers and students, the book is at once accessible and erudite, and it may be many years before it is dethroned as the volume most frequently recommended to readers new to the study of modern China. It takes its place alongside other excellent books by Spence, including The Gate of Heavenly Peace, To Change China, and The Chan’s Great Continent. Spence based the book on lecture materials for his popular intro to modern China class at Yale.

— Kaiser Kuo

The China Project Book List. Back to main Books List page