Who speaks for the Chinese government?

A guide to interpreting the utterances of state media.

As uncertainty surges in U.S.–China relations and observers struggle to derive signals about U.S. policy, there is a corresponding scramble to identify Chinese reactions to a U.S. leadership that regularly breaks from decades-long patterns.

Faced with breaking news and short deadlines, journalists have long amplified the most available sources, not necessarily the most authoritative ones.

After then-president-elect Donald Trump spoke by phone with Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-wen, a headline in The Guardian declared, “China should plan to take Taiwan by force after Trump call, state media says.” It based the headline on an editorial in the Global Times (GT), a mass-market subsidiary of the People’s Daily, the top Chinese government mouthpiece. The Guardian explained that GT “sometimes reflects views from within the Communist Party.” After Trump’s pick for secretary of state, Rex Tillerson, implied the U.S. military should potentially blockade China’s installations in the Spratly Islands, a GT-based CNN headline read, “Chinese state media slams Tillerson over South China Sea.”

Readers of China news will remember many other examples of GT and other bellicose media commentary standing in for “China’s voice” in media coverage, a trend that led one journalist to stage a one-woman Twitter campaign to #ignoretheglobaltimes, and another to declare reporters “need to stop taking the bait.”

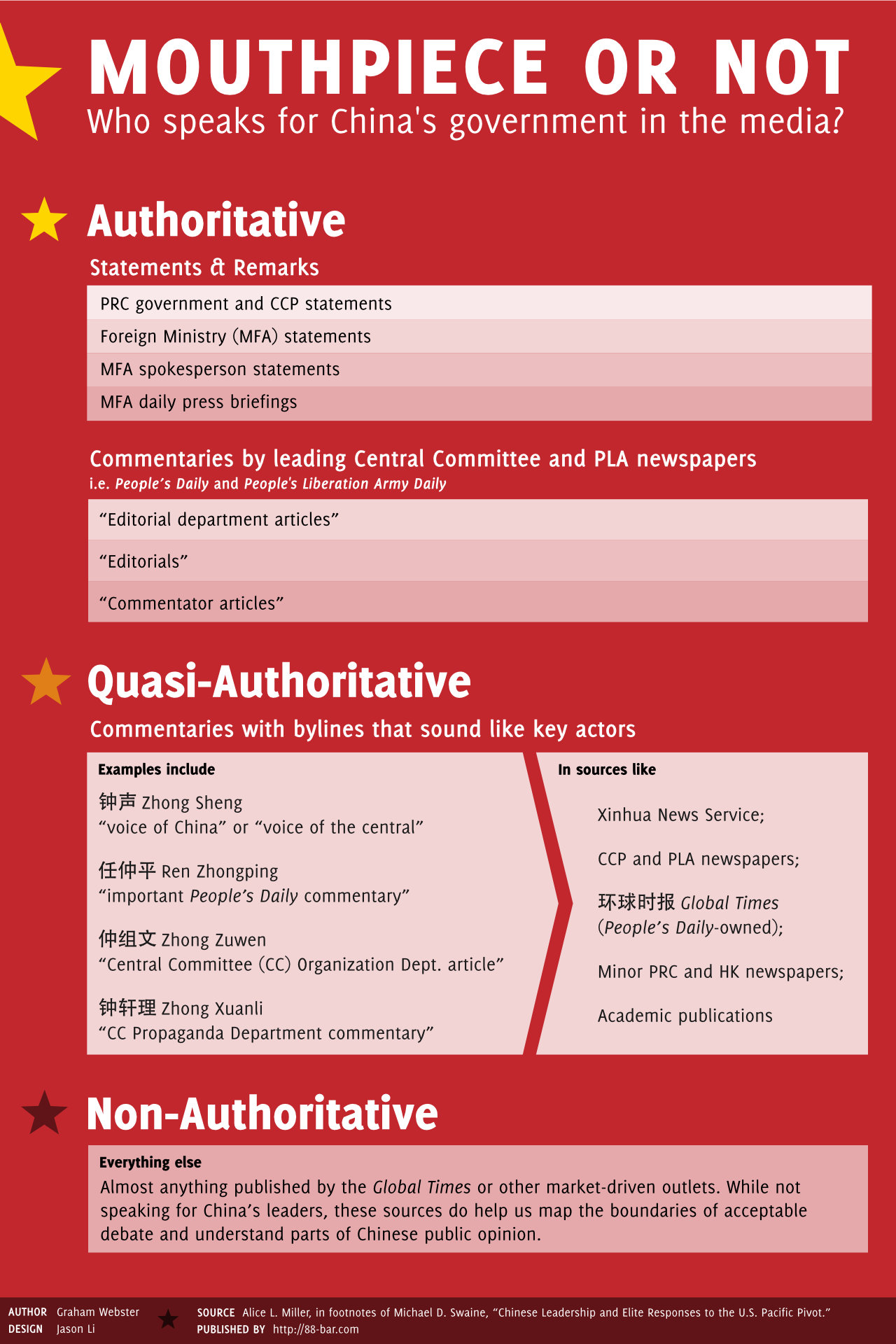

Though GT and many other outlets in China are officially state-run, some outlets and types of articles reflect top-level official opinion more consistently than others. A few years ago, Alice L. Miller — a former CIA China analyst and veteran scholar of China’s elite politics — provided a vivid rundown of authoritative, quasi-authoritative, and non-authoritative Chinese media sources. It can be found, of all places, in a remarkable footnote to a paper by Michael Swaine of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Based on Miller and Swaine’s insights, Hong Kong-based designer Jason Li and I compiled this visual guide to what’s authoritative and what’s not in media reflecting Chinese official opinion. We first published it at our group blog 88 Bar and updated the guide for The China Project this month.

The Chinese media regularly carry highly authoritative government messages in the form of speeches by top leaders or official statements from ministry spokespeople. Some kinds of commentary are also quite authoritative. As Miller told Swaine, “Authority of official comment is determined by the place of the issuer in the institutional hierarchy.” An editorial by People’s Daily, for instance, is highly authoritative since it represents the paper, thereby representing its sponsoring entity, the CCP Central Committee.

Swaine’s paper also highlights the phenomenon of “quasi-authoritative” commentaries published in prominent outlets under bylines that are not people’s names but instead homophones of the entities or roles they represent. China foreign policy watchers have become accustomed to periodic People’s Daily pieces by “Zhong Sheng” (钟声), which sounds like either the voice of China or the voice of the center, and Swaine remarks that those articles “[appear] to be written by the editorial staff of the People’s Daily international department.” Pieces signed by individual scholars or Party members don’t carry the same authority as commentary that is produced or approved by a committee. [UPDATE: In a later paper also assessing Chinese views, Swaine described Zhong Sheng articles as “at best … a higher, more prominent subset of non-authoritative sources,” though still “probably more ‘important’ than articles written by ordinary Chinese academics.’]

The GT can be seen as even less authoritative. As Swaine writes, quoting Miller: “Despite the view expressed by some pundits, nothing published in the GT is ‘authoritative’ in any meaningful sense, because the newspaper is a commercial vehicle and doesn’t stand for the People’s Daily, even though it is subordinate to that organ.”

Still, given that Chinese government statements or comparatively authoritative media pieces tend to take anywhere from a few hours to a couple days to emerge, what can observers learn from the GT and other “non-authoritative” but faster-reacting Chinese media?

“These early non-authoritative pieces are indications of domestic pressure that the Chinese government may be under, with the caveat that the government is allowing this pressure to exist,” said Jessica Chen Weiss, a political scientist at Cornell University whose book Powerful Patriots analyzes nationalist protest and the interplay between public opinion, media control, and Chinese foreign policy.

These sources also provide day-to-day insight about “the bounds of acceptable policy debate in China,” Weiss said. “And of course if a story is subsequently deleted, we know they went too far.” Meanwhile, Weiss said, a more “aggregate assessment of what the Chinese media are reporting” is often neglected and can provide insight into which developments Chinese authorities want the public to pay attention to and which they would rather downplay.

Though it’s not in the nature of journalism to cover what isn’t said and doesn’t happen, government priorities can also be found in leaks of purported internal censorship guidelines, often published by China Digital Times. Though it is hard to authenticate these documents, they often call for coverage of a sensitive issue to publish only Xinhua stories, so if sources that usually report in their own voice start posting only official wire, it is likely they’re following orders.

One such Xinhua-only order was reportedly issued a week before the Trump inauguration. According to CDT, the order said “any news relating to China-U.S. relations must use Xinhua copy. Any news about Trump must be handled carefully; unauthorized criticism of Trump’s words or actions is not allowed.”

Note: The image at the top of this story is the front page of the first issue of the Global Times when it was called Global News Digest (环球文萃 huánqiú wéncuì). It changed its name to Global Times (环球时报 huánqiú shíbào) for its second issue. You can find a brief history the newspaper here.