Where does Chinese Islamophobia come from?

It may be tempting to think that Islamophobia in China is imported from the West. That is partially true, but Han chauvinism, the Communist Party’s quest to secularize society, and China’s unique political and media environment make the fear of Muslims in the Middle Kingdom its own unique beast.

I am sitting with a small group of Chinese and Westerners on the dried-out grass in Beijing’s Chaoyang Park, in a prosperous part of eastern Beijing. Suddenly the conversation turns to China’s Hui Muslims, a minority of some 10 million people who live throughout the country. “Stupid cunts!” (傻屄 shǎbī) shouts Wang Zhen, a Chinese IT graduate and avid Trump supporter.

“What about the Uyghur?” somebody asks, referring to the predominantly Muslim group in Xinjiang, the far western province where the Communist Party stands accused of imposing draconian restrictions on religious freedom. “They are the biggest shabi,” says Wang, launching into a Jack Daniel’s-fueled tirade against both the Hui and the Uyghur, while his French fiancé tries to change the subject.

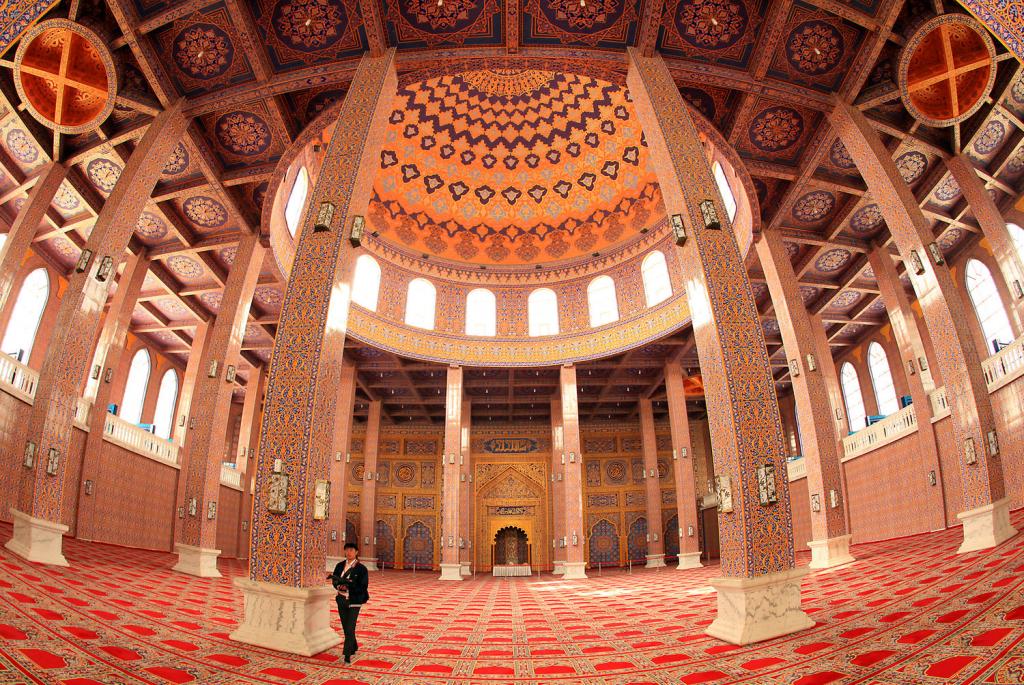

Wang is from Lanzhou, the capital of the north-central province of Gansu, which is home to a large Hui population. Historically, Lanzhou was an important stop on the northern Silk Road, where for centuries goods and ideas passed through Central Asia, linking East and West.

Wang is an extreme example, comparable with many individuals in America’s “alt-right.” But throughout my time in China, I have noticed an alarming prevalence of Islamophobic views at every level of society. And I was curious as to why these views, often directly imported from the West, seem to have found traction among so many Chinese people. After all, these same people were often quick to criticize Western intervention in the Middle East; they also surely had good reasons of their own to support attempts to counter Western political and cultural dominance.

Chauvinism of the “Great Han” majority

In China, as in other parts of the world, Muslims and other minority ethnicities have always faced some discrimination: A particular type of prejudice favoring the majority Han ethnicity, called Han chauvinism (大汉族主义 dà hànzú zhǔyì;literally Great Han-ism), has reared its head throughout the country’s history, and violence has erupted sporadically in places such as Yunnan, the southwestern province that is home to several substantial Hui communities.

So, is Chinese Islamophobia just a more pronounced extension of Han chauvinism? Certainly, in the arid northern regions where most Hui live, there is evidence of suspicion toward Muslims. Just south of Gansu Province lies Ningxia, a Hui autonomous region, where one week earlier my Chinese colleague had been urged to “be careful on the streets, [because the Hui] try to meet a ‘three-kill quota’ every year.” But hostility to Islam is being voiced beyond these regions.

As in North America and Europe, in China, proximity to Muslim people isn’t a prerequisite for Islamophobia. And Chinese Islamophobes don’t confine their outbursts to the Hui or Uyghur. A tour of Chinese social media turns up regular currents of hatred and suspicion, directed (in Chinese) at Islam and Muslims within and beyond China’s borders:

“Whether in China or abroad, Islam is essentially an evil cult — just take a look at some of the countries in the Middle East, then it’s clear.”

Or:

“When I look at a map of Muslim countries, I feel very scared…the threat is coming from the west, and also the south; apparently, Islamic terrorist organizations are actively trying to establish Islamic states in Malaysia, Indonesia, southern Thailand, and the southern Philippines.”

Some Islamophobes are now grafting fears about Muslim power networks onto local minority communities. One extensive article (originally published at this link, since deleted) outlined an elaborate conspiracy theory suggesting that the Hui are bolstering their power through a vast network of Halal restaurants — the most visible symbol of Islam for many Chinese people.

The writer (who claims to be Muslim) argues that Han patrons are unwittingly “subsidizing Islam” and thereby allowing the Hui to grow “their ranks.” They go on to link the conspiracy to Islamic extremism in Xinjiang and the Middle East (see also fears of “creeping Sharia” in China).

“Islamophobia is a global problem spurred on by often unrealistic fears of terrorism and extremism and the ability of new communication technologies to facilitate information cascades,’’ says James Leibold, professor of politics at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia, whose research focuses on race and ethnicity in China.

Many of the views expressed online, like that of Islam as inherently belligerent, intolerant, and backward, will be at least partially familiar to Western readers, as will the nationalist, xenophobic themes.

“The Western media has a very big influence on Chinese thinking about Islam,” says Professor Lin Fengmin 林丰民, director of the Arabic Language Department at Peking University, who has spoken publically about the demonization of Islam in the West. “The Chinese media introduces large amounts of secondhand information [from their Western counterparts].”

Lin adds that in Chinese academia as well, Western ideology still holds sway.

“The [Chinese] community researching Islam is expanding…led mainly by the Han,” but “[Arabic] language skills are still below par, and most of the material is in English or French, so lots of people absorb a Western worldview.”

Writing in the Chinese edition of Vice magazine, one Hui journalist argues that just as “China’s Muslims” are often derided as “spiritual Arabs,” their attackers can be seen as “spiritual Americans” or “spiritual Europeans,” unduly swayed by Western views and a distorted, thirdhand understanding of events in Europe and the Middle East.

And unfortunately, paranoia about Islam isn’t limited to angry online nationalists. A number of my educated and “liberal” Chinese friends express unabashed hostility to Muslims.

“Muslims have too much power in Europe,” said one of my former students, an otherwise kind, thoughtful, and internationally minded woman with a prominent position in state media. I had asked her whether she saw the election of London’s mayor, Sadiq Khan, a Muslim, as a sign of progress.

Co-opting Western ideology

In an increasingly globalized world, fear and prejudice are bonding China and the West, allowing both to view Islam as a hostile other.

The Chinese government’s attempts to co-opt the “global war on terror” for its interests in Xinjiang and its repressive measures like the ban on beards and veils are likely bolstering these prejudices, just as Trump’s attempted ban on Muslims has sanctioned open hatred — though the Communist Party usually implements its measures far less publically.

“The Chinese government seems to allow anti-Muslim hate speech to remain uncensored at strategic times,” says Leibold.

But do the attitudes that underlie such speech have an earlier historical precedent in the Middle Kingdom?

“Islamophobia existed in the West during the Middle Ages, but not in China…it’s been increasing [here] recently,” argues Lin, who believes that this increase might be due to violence in Xinjiang and Western efforts to divide China’s ethnic groups.

It is true that in China, a more syncretistic attitude to philosophy than is typical of Western culture has also helped promote social and political compromise — at least between the Han and Hui. The Qing dynasty Chinese Muslim scholar Liu Zhi 刘智, for example, remains renowned for his explication of and commentary on Islam using Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian terms.

Today, some Hui, who are ethnically similar to the Han majority, overtly distinguish themselves from the Uyghur, even describing their faith as “Islam with Chinese characteristics.”

A Hui academic, who asked that his name not be used, said that despite “some tensions,” relations between Han and Hui were “generally” good during the Republic of China period (1912–1949), which immediately preceded the arrival of the communists. He emphasizes that Sino-Muslims played an active part in shaping concepts of Chinese nationhood.

“The Islamic movement in China shared common ground with other Islamic movements overseas, particularly in the Middle East, but as a minority in China, Hui Muslims had no intention of building an ‘Islamic state’ or of competing with the Han,” he says.

The “civilized” communists arrive

It was not until the arrival of the communists in 1949 that the Hui, like other religious groups, began to face systematic persecution. During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), mosques were destroyed, and the Hui were forced to wear pig heads round their necks.

It was through the imported Marxist-Leninism above all that China received the conceptual, Enlightenment divide between the religious and the secular — a divide that some modern scholars of religion have come to see as suspect: The boundaries and indeed the essence of religion, they say, are particularly hard to define and often based on perceived distinctions between an individualistic Western Christianity and other areas of politics, society, and culture as defined in modern Europe.

This distinction was then applied to non-Western cultures, most of which did not have a discrete concept of “religion.” And to this day, those who do not clearly mark the difference between the “religious” and “the secular” tend to be ridiculed.

In China, the imported Enlightenment divide allows some Chinese to see themselves as more “civilized” and “scientific” than those whose politics or culture are deemed “religious.” This situation recalls how some of the “New Atheists” in the West — strong critics of religion who insist on the superiority of science over religion as a way to find truth — have been criticized for their view of Islam as an especially regressive, or uncivilized, force.

In China, this position is still expressed in Marxist terms, even while the excesses of recent Chinese history — the cult of Mao and the Cultural Revolution — had markedly “religious” overtones.

“There is still a fundamental tension between Marxist-Leninism and religion, and that affects policies toward minorities,” says Leibold, adding that many “assimilationists” in government, those who downplay or disdain ethnic differences, wish to continue down the road to secularization.

In typical Marxist-Leninist fashion, a grade-three textbook now used in Chinese high schools declares support for the temporary preservation of religious beliefs, while arguing for the need to “thoroughly eliminate” their roots: “poverty,” “delusion,” and “ignorance.” This is one of the most explicit references to religion in China’s school curriculum, which is otherwise nearly silent on the subject.

And if the notional divide between the religious and the secular is not as clear as most assume, the distinction that these textbooks later make between “normal” religion and “feudal superstition” is completely arbitrary.

What’s more, observers could be forgiven for assuming that the CCP, like other governments, simply tends to favor beliefs and practices that serve nationalistic interests.

Hence, President Xi Jinping, like many of his recent predecessors, has few qualms about supporting the Taoist Tao Te Ching, the Analects of Confucius, and traditional Chinese medicine, all of which arguably defer to the kind of transcendent phenomena and principles commonly associated with “religion.” The main difference is that these philosophies and practices are perceived as essentially Chinese, not Western or Middle Eastern.

Asked about his views on religion, my colleague’s father, a Chinese businessman in his fifties, said he accepted Mao Zedong’s perspective.

“Religion is superstition, and religious people are false and hypocritical.” Muslims, he added, are “quite barbaric.”

It follows that the prominent Islamophobe Xi Wuxi 习五一, previously professor of Marxism at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, frequently cites Marxist views of religion on her Weibo page. In between attacks on Hui, Uyghur, and Middle Eastern Muslims — including a recent post comparing 19th-century Hui rebel leader Bai Yanhu 白彦虎 to an Islamic State militant — she writes that “atheism is the cornerstone of socialism.”

Atheism is, she argues, essential to a “prosperous” and “civilized” society. A favorite of the Communist Party, the latter term has a distinctly colonial flavor.

Prejudice goes global

From East to West, currents of mutually supporting prejudice are increasing at a time when China is seeking to promote greater global integration, a response in part to Trump’s protectionism: At a summit on May 14, when China advertised the One Belt, One Road initiative, or New Silk Road project, Xi referred to globalization as “a big ocean that you cannot escape from.”

Touted as a modern-day rival of the ancient trade route, the multibillion-dollar infrastructure project runs straight through a string of Muslim countries.

Zee, a Pakistani Muslim who moved to the U.K. at the age of 21 and now teaches economics in Beijing, expresses cautious optimism.

“At least China is investing money in the region, which can reduce radicalization. But I really hope that China learns from the West’s mistakes, and that Muslim leaders in these countries are able to explain their people’s point of view.”

The Hui author of the Vice article on Islamophobia mentioned above begins with what the writer sees as a typically Islamophobic comment.

“Unlike the Christians and Buddhists we all know well, the Hui, though they can be found throughout the country and their Halal restaurants are almost everywhere — these Muslims are no more familiar to us than strangers.”

It remains to be seen what Xi’s new initiative will yield. But if the cultures at either end of the Silk Road continue to cast those in between as a sinister and pernicious other, the initiative is certainly less likely to promote a “win-win situation.”

Steve Chen contributed research to this article.