Yanbian looks south: How China’s borderland has turned its back on North Korea

As goodwill between Beijing and Pyongyang erodes, the residents of a Chinese border area find themselves increasingly attracted to another Korea, farther south, to find economic and social connection.

China and Korea have rarely let their 880-mile border divide them. For centuries, Korea was one of China’s tributary states, and revolutions and natural disasters in the 19th century as well as Japan’s occupation of the peninsula beginning in 1910 brought a century-long flood of Koreans into China — including Kim Il-sung, who attended middle school in the region, joined the Communist Party of China, and commanded a Chinese guerrilla unit against the Japanese before returning home to found North Korea in 1948. By the time Yanbian Autonomous Prefecture was formally established in 1952, the region’s ethnic Korean population had swelled to around 550,000 — from 10,000 in 1881 — many having migrated from what was now North Korea. Until recent decades, the border remained relatively open, with refugees spilling across at moments of instability in either of the two countries.

Consequently, many of those living in the borderlands have mixed heritages. In Yanbian, which shares a 324-mile border with North Korea, one in three people are Chinese Korean. Here, signs are written in both languages, restaurants cook up traditional Korean fare like cold noodles and dog, and a primary- and secondary-level education in Korean is compulsory for the ethnic minority population. The region is sometimes referred to as the “Third Korea.”

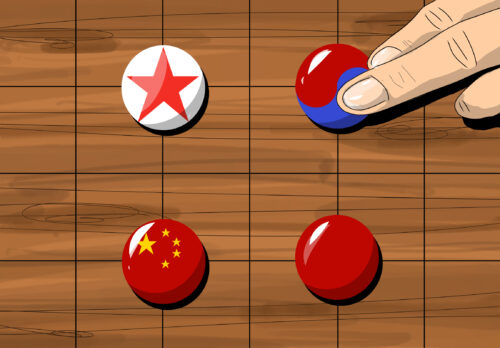

But while historical and cultural ties have long connected Yanbian’s Chinese Koreans to the Hermit Kingdom — specifically, with North Hamgyong, the province with which they share an international border and a dialect — the kinship has fallen on hard times as Beijing and Pyongyang’s alliance increasingly deteriorates. And as a centuries-old relationship is severed, Yanbian is courting a new flame: South Korea.

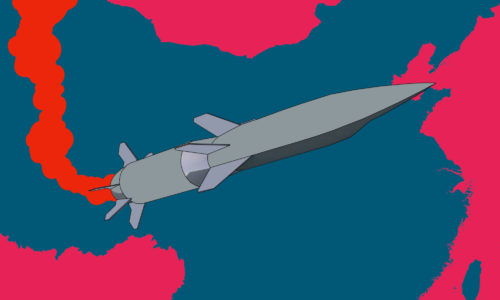

The break with the North is nothing new — Yanbian’s proximity to the border means that it’s often the first to suffer aggressions by the Kim regime. On September 3, North Korea reported that it had detonated a hydrogen bomb. Chinese news media Xinhua immediately posted a video on Twitter of a shaking chandelier in Yanji, the capital city of Yanbian, stating that “a 6.3-magnitude shallow earthquake struck North Korea.” This was the second time in a year that locals had felt the ground shake after weapons testing; in September 2016, the same thing happened when the Kim regime detonated its fifth nuclear bomb.

Nuclear weapons tests pose obvious environmental and health risks, but they also disrupt the day-to-day lives of Yanbian residents. Zhang Jinhua, a Chinese Korean native to Yanji, spoke to me about her old classmate: “He trades with the North Koreans. He sends textiles across the border and the North Koreans produce the clothes and resell to China. The labor is cheap in North Korea.”

There aren’t many places on earth that can manufacture textiles cheaper than China, but North Korea is one of them — its textile exports in 2016 were worth around $760 million. But unfortunately for entrepreneurs like Zhang’s friend, the Yanbian border periodically shuts down in response to aggressions from the Kim regime. “Every time they do a nuclear test, Yanbian will be affected a lot,” Zhang said. “It’s like an earthquake. Then the Chinese government says, ‘Okay, we’re closing the doors,’ and shuts the border.” After September’s nuclear test, China’s Ministry of Commerce announced a ban on all textile imports from the Hermit Kingdom.

Closing the border without warning disrupts commerce and decreases market confidence in reliable trade networks. Zhang said: “These businessmen, like my friend, don’t just do business with North Korea. They must have something else or they couldn’t survive.” Unsure whether the channels will remain open, many potential traders in Yanbian take their business elsewhere.

Another issue affecting stable relations, and an especially acute problem for frontier territories like Yanbian, is the inflow of North Korean illicit substances. Yanbian’s close geographic, cultural, and linguistic ties to North Korea help foster smuggling rings across the border. And although outside experts have identified and reported on the drug trafficking since the 1990s, the Chinese government didn’t acknowledge the problem until 2004, likely because of political sensitivity.

But eventually, Beijing could no longer ignore the problem. From 1995 to 2010, registered drug users in Yanbian increased 47.5 times, from 44 to 2,090. North Korea has long faced a severe crystal meth problem domestically — Pyongyang has manufactured the drug since the 1970s to raise money and motivate a starving population to work hellish overtime — but in recent years, Chinese authorities have stepped up efforts to contain the problem from spilling across the border. In 2010, China seized drugs originating from North Korea with a street value of $60 million, according to a South Korean government official.

Thus, in an age of hostile uncertainty, when China’s relationship with North Korea is at perhaps its worst ever, it’s no wonder that the people of Yanbian have begun forging commercial and social ties down south. A law passed in 1997 made it easier for Chinese Koreans to immigrate to South Korea, and by 2016, there were some 700,000 of them living as expatriates in the country. Comparatively, the Yanbian Korean population in 2016 was only 759,000.

This increased exchange has profoundly changed the borderlands. According to Changzoo Song, a senior lecturer at the University of Auckland who studies the Korean diasporic communities, “As a large number of Korean Chinese visited South Korea, they quickly imported South Korean culture and products such as food, fashion, books, public bathing houses, karaoke bars, and other popular cultural products and practices to China, including Yanbian.”

And as South Korea’s economy took off — since 1990, South Korea’s per capita GDP has more than tripled — educational and commercial opportunities abounded for Chinese Koreans. Money pouring into South Korean schools increased their global prestige, and a booming private sector opened new avenues of employment. Back in Yanbian, people began installing satellites and watching South Korean television, and a shift has even been occurring at the linguistic level. “Increasing numbers of Korean Chinese in Yanbian and other areas of China speak standard ‘Seoul’ Korean instead of their local dialects,” says Song.

The result has been a demonstrable north-to-south shift that has occurred in the space of a generation. According to Song, most Yanbian Koreans retained close contact with friends and relatives in North Korea until the mid-1980s, but today, these connections have almost all been severed. “Now, in Yanbian, ethnic Koreans do not pay too much attention to North Korea, which they deem poor and closed, and their lifestyle is heavily influenced by South Korean society,” he says.

China’s entry into the global order and North Korea’s unceasing aggressions have had profound effects on the country’s borderlands. Although Beijing continues to maintain relations with Pyongyang, this is mainly out of self-preservation — a collapse of the Kim regime would see hundreds of thousands of refugees swarm into China, as well as signal the end of Beijing’s buffer against a peninsula united under South Korea, a close United States ally. Yanbian’s shift south is just one of many examples of how globalization is changing China. As the country firmly establishes itself on top of a new international order, Chinese citizens are shedding their isolationist past and embracing a future of global interconnectedness.