The excesses of China’s social credit system

Invasions of privacy and a blacklist for small or subjective infractions are making many question the integrity of a system designed to promote integrity.

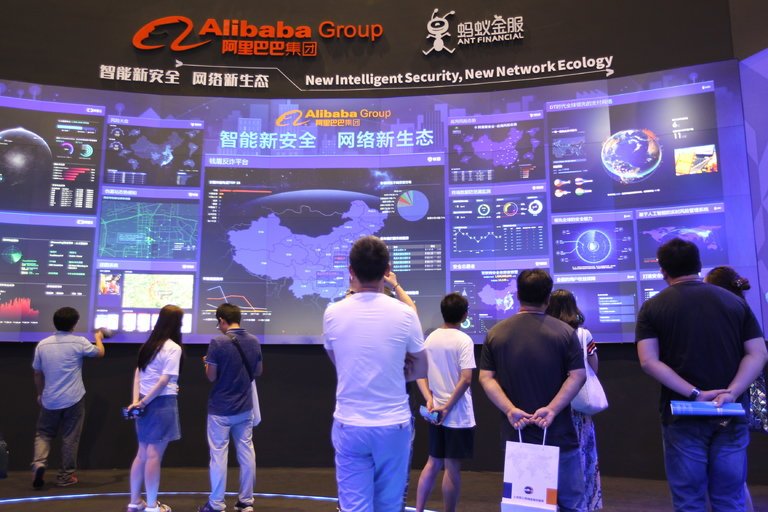

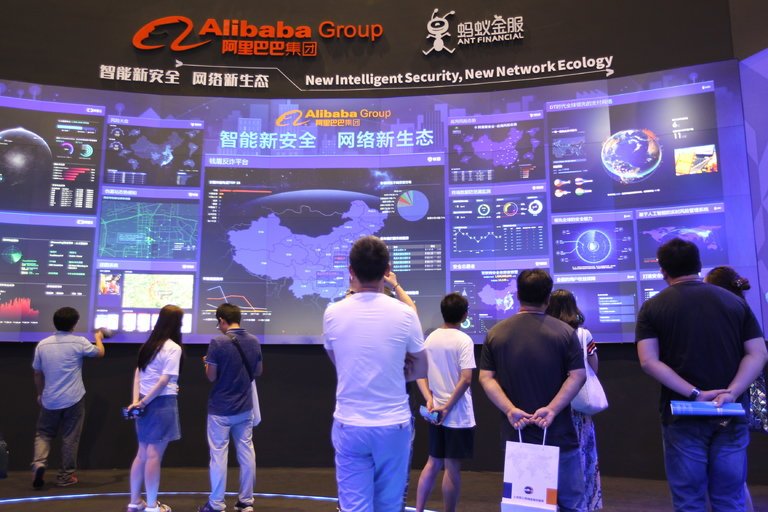

Sesame Credit (芝麻信用 zhīma xìnyòng) is the leader in the “social credit” industry, which aims to develop an all-encompassing system for ranking Chinese citizens’ trustworthiness, for both commercial and government security purposes.

- On January 3, the Alibaba subsidiary admitted to an “extremely stupid” design in its app’s settings that inconspicuously shared all users’ credit data with Alibaba’s separate payment app, Alipay, by default, Sixth Tone reports.

- The New York Times calls (paywall) the outcry over this a “rare, public rebuttal of a prevailing trend in China,” and evidence of “a nascent, but growing, demand for increased privacy and data protections online.”

- See a summary yesterday on The China Project about changes in China’s Nanny State and how citizens are reacting.

Separately, the Globe and Mail looks at another specific excess of China’s social credit system: a government blacklist called the List of Dishonest Persons Subject to Enforcement (失信被执行人名单 shīxìn bèi zhíxíngrén míngdān). It is a list of 7.49 million people, all of whom are restricted in their ability to purchase property, take out loans, buy train tickets, and more. It includes people like:

- A journalist who was punished for “spreading rumors” about official corruption, and then blacklisted without his knowledge when he refused to publish an apology to his social media account.

- A two-year-old girl who was assigned to bear her father’s debt, totaling $25,000, after he was executed in 2014 for murdering his wife. The girl’s grandfather told the Globe and Mail that she was now on the government blacklist because the debt was not paid off.

- A shoplifter of $70 worth of cigarettes, and others who had missed various payments worth less than $2,000.

The Globe and Mail talked with Lin Junyue, an “academic sometimes called the founder of China’s social-credit theory,” who admitted that the blacklist system has excesses, but says that he and many others still believe that its benefits outweigh its costs. Many of those others are the government’s policymakers, who “want the full system in place in three years,” as “they say it will bring about a more honest, trustworthy country.”

- Tibetan language activist charged with ‘inciting separatism’

Tibetan activist put on trial in China for inciting separatism / Guardian

Tashi Wangchuk, who criticized China’s Tibetan language education policies, appeared in a New York Times video. He “pleaded not guilty to the charges of ‘inciting separatism’ during the four-hour trial in the western Chinese city of Yushu, where the state’s main piece of evidence against him was the nine-minute video.” - Russia-China flashpoints

China land grab on Lake Baikal raises Russian ire / Financial Times (paywall)

“An online petition with 55,000 signatures (Listvyanka [the border town] has a population of less than 2,000) claims that Beijing is seeking to transform the area into a Chinese province, and asks Russia’s President Vladimir Putin to ban land sales to the Chinese there.” - Taiwan

Taiwan protests China’s unilateral launch of new flight routes / Focus Taiwan - Space

India and Japan prepare joint mission to the moon / Financial Times (paywall)

An “effort to counter [the] rise of China underlies [the] move to collaborate on space exploration.”

China boldly goes into space with 40 planned missions / Asia Times

China admits space lab will fall, but in ‘controlled way’ / Asia Times - LGBT

Beijing court accepts case requiring China’s censors to justify ban of gay content / Hollywood Reporter - Censorship

Tencent hires hundreds of content patrols with QQ virtual coins / TechNode

China’s great firewall is rising / Economist (paywall)

“Many observers believe that the Great Firewall’s porousness is a feature, not a bug — that its architects see benefit in a barrier that does not completely alienate entrepreneurs, academics and foreign residents, but which most Chinese web-users will not have the energy, or the finances (VPNs usually require subscriptions), to surmount. But doubts are growing about this interpretation.” - Snow in northern China

Heavy snowfall shuts three China airports, delays at nine others / Reuters