Re-education camps in China’s ‘no-rights zone’ for Muslims: What everyone needs to know

Update: For a more current look at the situation in Xinjiang, see our August 2019 article: China’s ‘social re-engineering’ of Uyghurs, explained by Darren Byler.

Adem yoq — “Everybody’s gone.”

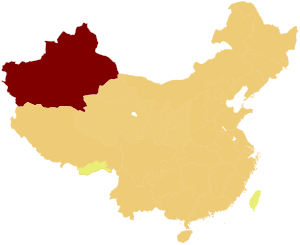

A human rights atrocity is unfolding in western China, where the “entire culture” of Uyghur Muslims is being effectively criminalized, scholars say. Arbitrary detentions in “transformation through education” centers have reportedly reached up to 1 million Muslims in the Xinjiang region.

Let us explain.

Contents (click to jump to section):

Timeline of recent reporting, from October 2017 to present

Re-education camps: What we know

“Crimes” and punishment • Prominent Uyghurs detained • UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

China’s response

“There is no such thing as so-called ‘re-education camps’ in Xinjiang”

Why now?

Chen Quanguo • Belt and Road • “Stability”

The bigger story: Global significance

Uyghurs abroad • Experimental surveillance • International response • Journalist harassment

Top photo: One of the few publicly available images of mass incarcerated ethnic minorities in the Xinjiang region of China shows inmates of the “Lop County number 4 education and training center” (洛浦县第四教育培训中心 luòpǔ xiàn dì sì jiàoyù péixùn zhōngxīn) listening to a “de-extremification” (去极端化 qù jíduān huà) speech on April 7, 2018. Photo identified by Concerned Scholars of Xinjiang, full-resolution image courtesy of Twitter user @AYNUR22630941, original source archived here.

Who are the Uyghurs and what is happening in Xinjiang?

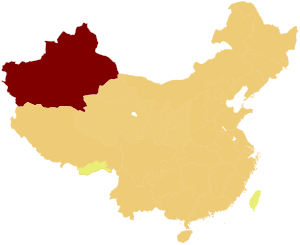

- Uyghurs are a Muslim Turkic-speaking ethnic minority in China. Uyghurs (also spelled Uighur — either way, pronounced WEE-gur) — about 10 million people — live mostly in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), the farthest west and most heavily Muslim jurisdiction under Beijing’s control. The total population of Xinjiang is around 22 million.

- After ethnic riots in Xinjiang’s capital, Urumqi, in 2009 that left nearly 200 people dead — and following Uyghur-connected terrorist attacks in Beijing in 2013 and Kunming and Urumqi in 2014 — extreme measures have been taken to lock down Xinjiang and restrict the mobility and speech of the Uyghur population.

- Xinjiang is now a totalitarian police state of historic proportions — it is widely cited as one of the most heavily policed places in the world today. Public security budgets have skyrocketed and futuristic surveillance systems have been pioneered in the region. As a result, over 20 percent of all criminal arrests in China happens in Xinjiang, despite the fact that the region contains only 1.5 percent of the country’s population.

- The official justification for such extreme measures is “counterterrorism” and “social stability.” But human rights groups have long argued that the level of repression is excessive, counterproductive, and a human rights violation, as it effectively censures all expressions of Uyghur culture, even normal religious and linguistic traditions.

- Alarming reports of a mass internment system have come out in the past year. Adrian Zenz, a researcher at the European School of Culture and Theology in Korntal, Germany, revealed the scope of the internment campaign and documented that construction of the camps began in earnest in March 2017.

- In the camps, officials seek to brainwash prisoners to disavow Islam and pledge loyalty to the Communist Party, and torture those who refuse, eyewitnesses have said.

- Arbitrary detentions without charge or trial are the norm for prisoners in these camps, and ethnically Kazakh Muslims have been “disappeared” in large numbers along with Uyghurs. Common “crimes” are “viewing foreign websites, taking phone calls from relatives abroad, praying regularly or growing a beard.” The widespread use of arbitrary detention is also being used as a tool to force Uyghurs abroad into silence.

- Up to a million Muslims have been put in the camps in Xinjiang, according to “many numerous and credible reports,” a United Nations panel said in early August 2018. The panel also called Xinjiang a “no rights zone” based on the reported mass internment program.

- China has specifically denied that “re-education” camps exist, but this is semantics: Evidence continues to build of a network of centers for “transformation through education” (教育转化 jiàoyù zhuǎnhuà) or “counter-extremism education” (去极端化教育 qù jíduān huà jiàoyù) holding many hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs and other Muslims in Xinjiang.

- “An entire culture is being criminalized,” scholars like Rian Thum are saying. Another scholar, James Millward, comments: “In Xinjiang, the definition of extremism has expanded so far as to incorporate virtually anything you do as a Muslim.”

From day-to-day discrimination to systematic, mass detentions

For years, Uyghurs have complained of day-to-day discrimination, both in Xinjiang and around the country. Islamophobia is widespread in China, and policies that repress Uyghur culture and religion — such as bans on long beards and religious veils, and multiple campaigns to force Uyghurs to change “overly religious” names — have been justified in the name of “counterterrorism.” Human rights activists like Amnesty International’s Nicholas Bequelin draw a “direct line” from the American “war on terror” to the Chinese campaign that took the name “People’s war” against terrorism in 2014, and targeted Uyghurs.

These political re-education camps technically fit within the definition of “concentration camp”

But everything is much worse now, reports from the last year indicate. Some of these reports focused on the intensification of surveillance and police control, which has reached totalitarian levels. But even more alarmingly, these reports began to reveal the massive scope of arbitrary detentions in a vast system of political re-education camps. These facilities technically fit within the definition of “concentration camp,” as reports indicate that the detainees are targeted for their affiliation with a religious and cultural minority, held extralegally without indictment or fair trial, and subject to conditions clearly designed to reinforce the state’s political control. Here is a timeline of the major reports on the security state, and the re-education camps:

- October 2017: Megha Rajagopalan at BuzzFeed News publishes a report based on interviews with more than two dozen Uyghurs, in Xinjiang and abroad, documenting “what a 21st-century police state really looks like,” including some details of Uyghurs being detained at re-education centers.

- November 2017: Emily Feng at the Financial Times reports that “Thousands have been sent to unmarked detention centres over the past year, usually for two to three months at a time. Nearly every Uighur resident interviewed by the Financial Times had a friend or relative who had been detained. In the centres they are taught Communist party doctrine and persuaded to forgo their ethnic and religious identities.” One Uyghur man told the FT that they are “political education centres,” which are “just like a university, only you cannot leave.” This report also contained new details on ethnic Kazakhs being detained, and on the expansion of the security state.

- December 2017: Josh Chin and Clément Bürge at the Wall Street Journal document the omnipresent security measures in multiple cities in Xinjiang, and analyze public data and interview a Uyghur who escaped Xinjiang and applied for political asylum in the U.S., telling a story of how the surveillance and security in Xinjiang “overwhelms daily life,” particularly for Uyghurs.

- December 2017: Human Rights Watch says that an unprecedented DNA collection program has been launched in Xinjiang, compiling the “fingerprints, iris scans, and blood types of all residents in the region between the age of 12 and 65.” The organization said that the DNA collection is “done surreptitiously, under the guise of a free health care program.” Earlier reports had shown that Xinjiang police were “in the process of purchasing at least $8.7 million in equipment to analyze DNA samples.”

- December 2017: Gerry Shih at the Associated Press publishes a series of four articles (he discussed this reporting on the Sinica Podcast) on how in Xinjiang, the “thought police instill fear,” how the “crackdown on Uighurs spreads to even mild critics,” and how Uyghurs abroad are fighting for and against jihadist forces. The first article reveals that at least some residents in Xinjiang are “being graded on a 100-point scale,” adding, “Those of Uighur ethnicity are automatically docked 10 points. Being aged between 15 and 55, praying daily, or having a religious education, all result in 10 point deductions.” The Wall Street Journal’s report contained what appears to be the same or a very similar rating form:

Here's an annotated copy of the personal data collection form police in Urumqi sent out to all residents early this year. It divides people into "safe," "normal" and "unsafe" based on categories like ethnicity and prayer habits. (More here: https://t.co/BB18uANBej) pic.twitter.com/CM28SOGNHK

— Josh Chin (@joshchin) December 20, 2017

- January 2018: Radio Free Asia, a U.S.-funded media outlet, reports, “Around 120,000 ethnic Uyghurs are currently being held in political re-education camps in Kashgar prefecture of northwest China’s Xinjiang region alone, according to a security official with knowledge of the detention system.”

- February 2018: Foreign Policy publishes the account of one Uyghur university student who returned to China from the U.S., was intensely interrogated, held in a re-education camp for 17 days without charge, and then released. A local police officer warned him, “Whatever you say or do in North America, your family is still here and so are we.”

- April 2018: The U.S. State Department says that detentions at political re-education centers of Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in Xinjiang number “at the very least in the tens of thousands.”

- May 2018: Human Rights Watch reports that hundreds of thousands of Communist Party members have been dispatched for “home stays” in mostly Muslim households in Xinjiang, part of a larger project of political indoctrination and human surveillance.

- May 2018: Adrian Zenz, a researcher at the European School of Culture and Theology in Korntal, Germany, publishes “New evidence for China’s political re-education campaign in Xinjiang” in the Jamestown Foundation’s China Brief. Zenz estimates that “between several hundred thousand and just over one million” people can be held in the facilities that have been built in Xinjiang since March 2017.

- May 2018: Gerry Shih and Simon Denyer of the Associated Press and Washington Post, respectively, publish some of the first named eyewitness reports from detainees in those re-education camps. Some sources allege torture in the camps, and all sources confirm a program of political indoctrination that seems to exclusively target ethnic minorities.

- July 2018: Megha Rajagopalan at BuzzFeed again publishes on Xinjiang, this time focusing on how China is blackmailing Uyghurs abroad to spy for China with the threat of sending their relatives back home to re-education camps. Ten Uyghur exiles all confirm to BuzzFeed, with voice recordings and messages as evidence, that they were coerced to help a campaign “aimed not only to gather details about Uighurs’ activities abroad, but also to sow discord within exile communities in the West and intimidate people in hopes of preventing them from speaking out against the Chinese state.”

- July 2018: The NGO Chinese Human Rights Defenders reports that government data shows the following: “Criminal arrests in Xinjiang accounted for an alarming 21% of all arrests in China in 2017, though the population in the XUAR [Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region] is only about 1.5% of China’s total.”

21 percent of all criminal arrests in China happens in Xinjiang, despite the fact that the region contains only 1.5 percent of the country’s population.

- July 2018: Emily Feng at the Financial Times reports that “In early 2017, Xinjiang began building dozens” of orphanages for the children of families that had been taken away to re-education. “One county in Kashgar built 18 new orphanages in 2017 alone, according to local media,” the FT notes.

- July 2018: An ethnically Kazakh Chinese national, Sayragul Sauytbay, escapes Xinjiang to neighboring Kazakhstan, and testifies in court that she had been told to teach at a re-education camp with 2,500 prisoners. She testifies that “they call it a political camp, but really it was a prison in the mountains,” and that its existence is a “state secret.” Her testimony is posted on YouTube, she was later interviewed by Nathan Vanderklippe at the Globe and Mail (notably, she confirms that the detainees were “all ethnic minorities”), and the story of her family and other Kazakh witnesses to the camps was told by Emily Rauhala in the Washington Post.

- July 2018: Gene Bunin, a Uyghur-speaking foreign academic who is currently undertaking a project to document Uyghur food and culture across China, writes that of the 1,000-plus Uyghurs he has spoken to in the past year, “almost everyone I talked to was significantly affected by the repression in Xinjiang,” adding that “the phrase adem yoq (‘everybody’s gone’) is probably the one I’ve heard the most this past year.” The Guardian republishes this unique account of the situation, headlined with the phrase one Uyghur security officer used to describe the situation to Bunin: “We’re a people destroyed.”

- August 2018: Chinese Human Rights Defenders reports: “In the villages of Southern Xinjiang, about 660,000 rural residents of ethnic Uyghur background may have been taken away from their homes and detained in re-education camps, while another up to 1.3 million may have been forced to attend mandatory day or evening re-education sessions in locations in their villages or town centers, amounting to a total of about 2 million South Xinjiang villagers in these two types of ‘re-education’ programs. The total number for Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR or Xinjiang) as a whole, including other ethnic minorities and city residents, is certainly higher.”

- August 2018: The UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) says that it has received “many numerous and credible reports” that as many as 1 million Uyghurs are being held in a “massive internment camp that is shrouded in secrecy.” (Reuters)

- August 2018: The New York Times reports that Rahile Dawut, a widely celebrated ethnographer of Uyghurs, is the latest scholar to be apparently locked up in the effective criminalization of Uyghur culture.

- August 2018: The Wall Street Journal again reports on the situation in Xinjiang, this time focusing on the re-education camps: Eva Dou, Jeremy Page, and Josh Chin co-author a piece titled “China’s Uighur camps swell as Beijing widens the dragnet.” They interview “six former inmates” of the camps, who confirmed the conditions in the camps described to the Associated Press, the Washington Post, and others previously, as well as “three dozen relatives of detainees, five of whom reported that family members had died in camps or soon after their release,” and draw on satellite maps to show the rapid, recent expansion of particular camps.

- August 2018: The U.S. State Department raises its estimate of detainees in Xinjiang to match or exceed the UN estimate: “The number of individuals held in detention may possibly number in the millions,” an official said, warning China that “indiscriminate and disproportionate controls on ethnic minorities’ expressions of their cultural and religious identities have the potential to incite radicalization and recruitment to violence.”

- August 2018: BuzzFeed journalist Megha Rajagopalan is forced to leave China after her journalism visa application is denied by authorities without explanation.

What do we know about the re-education camps?

For one, we know that the system of detention centers already built in Xinjiang is massive. Jerome Cohen, one of the most authoritative scholars of China’s legal system, writes that it’s probably the largest mass detention program in China in 60 years: “Perhaps the last time so many people have been detained outside the formal criminal process was in the 1957–59 ‘anti-rightist’ campaign.” A few sources in particular have attempted to quantify the progression and extent of the mass detention campaign:

- Public records of 73 government construction contracts prove that at least 680 million yuan ($108 million) has been spent on building detention centers in Xinjiang since March 2017, according to research by Adrian Zenz, a researcher at the European School of Culture and Theology. Zenz notes that March 2017 also saw the first reports of mass detentions, which “coincides neatly with the publication [in Chinese] of ‘de-extremification regulations’ (新疆维吾尔自治区去极端化条例) ” by the regional government on March 29, 2017.

- The network of detention camps in Xinjiang can hold up to a million inmates, Zenz estimates, and a “leaked document” from public security agencies “could indicate a detention rate of up to 11.5 percent of the region’s adult Uyghur and Kazakh population,” he writes.

- An average detention rate of 12 percent or more was confirmed by eight Uyghur interviewees in different towns in Xinjiang to Chinese Human Rights Defenders, which concluded:

“In the villages of Southern Xinjiang, about 660,000 rural residents of ethnic Uyghur background may have been taken away from their homes and detained in re-education camps, while another up to 1.3 million may have been forced to attend mandatory day or evening re-education sessions in locations in their villages or town centers, amounting to a total of about 2 million South Xinjiang villagers in these two types of ‘re-education’ programs. The total number for Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR or Xinjiang) as a whole, including other ethnic minorities and city residents, is certainly higher.”

- These and other reports led the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) to say that it suspected that 1 million Uyghurs are currently being held in a “massive internment camp that is shrouded in secrecy.” (CERD report)

- Thirty-four camps and counting have been identified in satellite pictures by Shawn Zhang (on Medium; on Twitter), a law student at the University of British Columbia.

- Satellite images show continued, rapid construction of camps, according to the Wall Street Journal.

From the print story, here’s how one camp in Kashgar expanded over the last year. The first image is from when the “de-extremification” campaign was beginning in April 2017 pic.twitter.com/2eUimDKDI9

— Eva Dou (@evadou) August 18, 2018

We also know that detentions are arbitrary. There is no criminal process or trial preceding before victims are sent to political education. As Megha Rajagopalan at BuzzFeed News noted in October 2017: “Detention for political education of this kind is not considered a form of criminal punishment in China, so no formal charges or sentences are given.”

- “Crimes” often have little or nothing to do with actual Islamic extremism, which is what China is supposedly trying to stamp out: BuzzFeed reported that “having a relative who has been convicted of a crime, having the wrong content on your cell phone…appearing too religious…having traveled abroad to a Muslim country, or having a relative who has traveled abroad” is enough to land Xinjiang residents in camps, but “viewing a foreign website, taking phone calls from relatives abroad, praying regularly” or even just “growing a beard” is enough to do it, according to the Associated Press.

- Punishments include torture, such as being chained up by wrists and ankles for hours or days, or being waterboarded, and conditions at the camps can be extremely unsanitary and crowded, witnesses have told the Associated Press, the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal.

- Detainees are told to denounce Islam, and are forced to repeat Communist Party slogans and sing Red songs for hours every day.

- There is an actual educational component — inmates learn Mandarin Chinese, for example — but subjugating the Muslim population in Xinjiang and Uyghur dissidents abroad seems to be the primary purpose of the camps. “Glowing state media reports have bragged about reeducation camps as free facilities that enable Uighurs to self-improve and see the error of ‘backward’ religious practices like excessive prayer or wearing religious garb. But the fact that state security operatives use the prospect of these camps as a threat to Uighurs contradicts this notion, suggesting they know that it is, in fact, a punishment,” Megha Rajagopalan wrote in her second report on Xinjiang.

- There is no clear legal basis for the camps, Jeremy Daum writes at China Law Translate: “The Xinjiang Regulation on De-extremification similarly uses ‘education’ as the lowest form of punishment, for situations not even meriting administrative punishments, but it would defy logic to read this as authorizing longer detention than the 15 days maximum authorized for the more serious violations.”

- Some detainees have died in the camps, “mainly, but not all, older people,” Uyghurs outside of China told the Wall Street Journal.

Prominent Uyghur individuals have been detained, in addition to hundreds of thousands of innocent common people. Rachel Harris of SOAS London lists them:

- Professional football player Erfan Hezim, detained in 2017.

- Prominent religious scholar Muhammad Salih Hajim, 82, died in custody [40 days after he was reportedly detained], January 2018.

- Xinjiang University president Tashpolat Teyip, detained in 2017, accused as a “two-faced” official, insufficiently loyal to the state.

- Xinjiang University professor Rahile Dawut, detained in 2017, possibly in connection with her ethnographic research on Uyghur religious culture.

- Uyghur writer and Xinjiang Normal University professor Abduqadir Jalaleddin, detained in January 2018.

- Elenur Eqilahun, detained in 2017, possibly for receiving calls from her daughter, who is studying abroad.

- Pop star Ablajan Ayup, detained in February 2018, possibly for singing about Uyghur language education.

- Halmurat Ghopur, vice provost of Xinjiang Medical Institute, detained in 2017 for exhibiting “nationalistic tendencies.”

Ilham Tohti, the Uyghur writer and economics professor serving a life sentence in China on trumped-up separatism-related charges, is not included in this list. He was detained in 2014.

China’s oddly specific denial

International attention focused on the situation in Xinjiang came in early August, as Chinese representatives were called to answer questions by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) in Geneva, Switzerland. On August 10, Gay McDougall, vice-chair of CERD, said:

We are deeply concerned at the many numerous and credible reports that we have received that in the name of combating religious extremism and maintaining social stability (China) has changed the Uighur autonomous region into something that resembles a massive internment camp that is shrouded in secrecy, a sort of “no rights zone.”

Yemhelhe Mint Mohamed, another panel member at CERD, raised concerns over the “arbitrary and mass detention of almost 1 million Uighurs.”

On August 13, the Chinese delegation to CERD responded. At 1:08:44 in this video recording of the UN testimony (in Chinese), you can hear a member of the Chinese delegation, Hu Lianhe 胡联合, issue this specific denial: “There is no such thing as so-called ‘re-education camps’ in Xinjiang” (新疆不存在所谓的‘再教育中心’ xīnjiāng bù cúnzài suǒwèi de ‘zài jiàoyù zhōngxīn’).

Chinese officials often use the phrase “so-called” (所谓的 suǒwèi de) when dismissing what they see as Western Lies, but here it is apparently used literally: The Chinese government does not call them “re-education camps.”

Instead of the term “re-education camp” (再教育中心 zài jiàoyù zhōngxīn), the Chinese government officially calls these facilities things like “transformation through education” (教育转化 jiàoyù zhuǎnhuà) or “counter-extremism education” (去极端化教育 qù jíduān huà jiàoyù) centers in Chinese, Adrian Zenz documents in his research.

But while the Chinese delegates called the figure of 1 million detainees “completely untrue,” and declined to give their own figure on the number of those detained, the Wall Street Journal reports that they did admit that at least some Xinjiang residents who had been imprisoned in anti-terrorism campaigns had been taken to “vocational education.”

“I noticed you didn’t quite deny these re-education or indoctrination programs,” Gay McDougall said in closing remarks at the hearing.

This is normal practice for China, as BuzzFeed wrote in October 2017: “Chinese state media has acknowledged the existence of the centers, and often boasts of the benefits they confer on the Uighur populace” — though true numbers on the extent of detentions have never been admitted by the government.

Why is this happening in Xinjiang, and why now?

Similar to Tibet, Xinjiang has been subject to various degrees of control by Chinese emperors for centuries but was only really incorporated into China during the 18th century. Xinjiang briefly regained independence in the early 20th century before being subjugated again by the People’s Republic of China in 1949. The government has since then continually sought to identify and crush individuals and groups supporting “separatism” in both regions.

But Xinjiang is different in one obvious way: It is China’s most heavily Muslim region. Relations between the Chinese government and China’s ethnic minorities are complicated, and Islamophobia is a complex, deeply rooted problem in the country. Rachel Harris of SOAS London writes that “strike hard” campaigns against Uyghur separatism were common throughout the 1990s, but that this morphed into a “People’s War on Terror” — and “counterterrorism” became a primary justification for harsh policies clamping down on Uyghurs — “soon after the September 11 attacks on the United States.”

“Counterterrorism” was increasingly relied on to justify the continued “strike hard” campaigns and “war on terror” in Xinjiang, following Uyghur-connected terrorist attacks in Beijing in 2013 and Kunming and Urumqi in 2014.

Then, two factors have accompanied the Uyghur repression going dramatically into overdrive in the past couple of years.

The first is Communist Party official Chen Quanguo 陈全国.

Scholars who study ethnic policies and domestic security in China, like Adrian Zenz and James Leibold, are quick to point out that Chen, whose securitization strategies were proven in Tibet, brought many of his same strategies to Xinjiang when he was transferred as Party Secretary from Tibet to Xinjiang. He is particularly well known for establishing “convenience police stations” (便民警务站 biàn mínjǐng wù zhàn), or small outposts to maintain order set every few hundred feet along major roads, and for perfecting the Party’s “grid-style social management” (社会网格化管理 shèhuì wǎnggé huà guǎnlǐ), a system of all-encompassing surveillance. Chen’s firm grip produced the result the Party wanted: no major social unrest in Tibet for five years during Chen’s entire time in power from 2011 to 2016 (though there was a spike in protests by self-immolation).

Since Chen was transferred to Party Secretary of Xinjiang in 2016, he has applied the same techniques. In his first year, the regional government “advertised more than 84,000 security-related positions…nearly 50 percent more than it did in the past 10 years,” the South China Morning Post reported. The Wall Street Journal notes, “During the first quarter of 2017, the government announced the equivalent of more than $1 billion in security-related investment projects in Xinjiang, up from $27 million in all of 2015, according to research in April by Chinese brokerage firm Industrial Securities.” When Wall Street Journal reporters visited Xinjiang a year ago, they found that the “surveillance state overwhelms daily life” — even entering and leaving a grocery store requires passing through a checkpoint, and many Uyghurs with black marks on their records are unable to pass checkpoints. Criminal arrests in Xinjiang — which do not even account for the hundreds of thousands of re-education camp detentions, which occur outside the legal system — have skyrocketed 731 percent from 2016 to 2017.

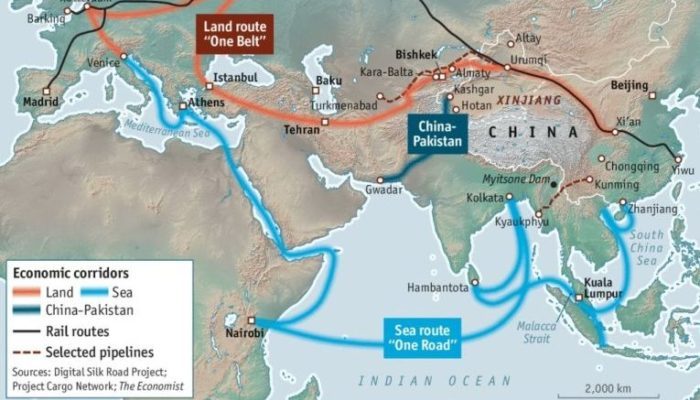

The second is the Belt and Road Initiative.

General Secretary Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy seeks to build infrastructure and new trading relationships across Eurasia, and Xinjiang is an essential crossroads of two major parts of Belt and Road: The land “belt” part, which goes through Urumqi and passes into Kazakhstan, and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which starts in Kashgar and ends at the important seaport of Gwadar. The ambition of the Belt and Road has greatly expanded in the past two years, just like the repression in Xinjiang. The Belt and Road cannot succeed without stability in Xinjiang, the thinking goes, so the Party took extreme measures to ensure that stability.

The underlying factor, and prime justification the Party always claims, is “stability”

For years, the Party has avoided trying to justify its harsh measures in Xinjiang to an international audience, choosing instead to focus on the broad benefits of securitization and social stability programs. For instance, the Global Times, which often reflects, but does not officially represent, official opinion in Beijing, argued on August 12 that “the high intensity of regulations” and ubiquitous “police and security posts” are necessary to maintain peace and ensure future development in Xinjiang. It further assures us that a “transition to normal governance” will resume at some unspecified future time. And as it summarized in the tweet of the article:

Official statements in recent weeks were at first more circumspect, but that appears to be changing. Here’s what officials have said so far:

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, to the Washington Post on August 10: “I only want to emphasize that at the moment, the overall situation of Xinjiang society is stable, the momentum of its economic development is good and ethnic groups live in harmony.”

- Lu Kang, Foreign Ministry spokesman, to Xinhua on August 14: “Some anti-China forces have made false accusations against China for political purposes… The people of all ethnic groups in Xinjiang cherish their happy and peaceful life.”

- Liu Xiaoming, Chinese ambassador to the U.K. on August 20 (Financial Times paywall): “The education and training measures taken by the local government of Xinjiang has not only effectively prevented the infiltration of religious extremism and helped those lost in extremist ideas to find their way back but also provided them with employment training in order to build a better life… Every country needs to tackle this challenge effectively. It is time to stop blaming China for taking lawful and effective preventive measures.”

The very fact that so many Uyghurs have been detained has pushed the entire Uyghur diaspora into a state of anxiety.

Adrian Zenz, a leading scholar studying the Xinjiang camps, who is cited many times above in this article, pointed out that “effective preventive measures” means mass internment in re-education camps, and this is an “evident shift from denial to justification” that we are seeing unfold.

Robert Barnett, a scholar of Tibet and Xinjiang, says that the inspiration for mass re-education in Xinjiang actually came from Tibet. He says, “my understanding of the decision to return to mass re-education rather than relying only on securitization was that it was presented to (or imposed on) Chen Quanguo in Tibet in 2011 by the inspection teams sent by Beijing for 3 yrs to assess the causes of 2008 unrest.”

James Leibold, a scholar of ethnic relations in China, wrote in 2012 that there were then calls for a “major rethink of ethnic policies,” and that a “series of bloody ethnic riots” in the previous decade had made the nationalistic arguments for mass assimilation much more popular. We can only assume that since 2012, with continued Uyghur terrorist attacks and unrest in Xinjiang, the Party has decided to go all-in on a mass assimilation policy in Xinjiang.

Why this isn’t just a ‘thing happening in a remote part of China’

In short, the way that China is treating Uyghurs, and information about Uyghurs, shares many similarities with how China treats dissidents around the world and information unfavorable to the Communist Party broadly. As China hones its techniques to repress and silence Uyghurs in Xinjiang and elsewhere, there is no reason to think it won’t apply the same techniques to more and more people. There are a few aspects to this:

Uyghurs abroad are being blackmailed into silence by China

There have been reports for years that China was exerting pressure on Uyghurs abroad — see, for example, a The China Project roundup of a few stories in August 2017: A chill for Uyghurs sweeps across the Mediterranean. Also see a report by Emily Feng at the Financial Times from the same time that indicated, “Chinese officials have since May been sending notices to overseas Uighur students demanding their immediate return — often after detaining their parents in China,” and that “about 150” Uyghur students at Al-Azhar University in Cairo, Eygpt, had been detained by local authorities, with at least 22 being deported.

But the threat of re-education camps has recently become a primary method of blackmail. Megha Rajagopalan’s July 2018 report in BuzzFeed cited “10 people in the exiled Uighur community who were targeted by Chinese state security after they moved overseas,” and “every person interviewed…said state security operatives told them their families could be sent to, or would remain in, internment camps for ‘reeducation’ if they did not comply with their demands. It was a campaign, they said, that aimed not only to gather details about Uighurs’ activities abroad, but also to sow discord within exile communities in the West and intimidate people in hopes of preventing them from speaking out against the Chinese state.”

And although “China has used such tactics since at least the 1990s to put pressure on those it believes are seeking to undermine the state,” the campaign against Uyghurs “has gotten far more aggressive over the past two years and has been bolstered by digital surveillance tactics.”

Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian has also written two pieces on Chinese pressure on specific Uyghur communities abroad: “Chinese cops now spying on American soil,” in the Daily Beast, and “Chinese police are demanding personal information from Uighurs in France,” in Foreign Policy.

The very fact that so many Uyghurs have been detained has pushed the entire Uyghur diaspora into a state of anxiety. The Globe and Mail tells some of these stories: “Exporting persecution: Uyghur diaspora haunted by anxiety, guilt as family held in Chinese camps,” and “Uyghurs around the world feel new pressure as China increases its focus on those abroad.”

Why would we doubt that these newly honed techniques wouldn’t be applied — or aren’t already being applied — to all sorts of dissident groups abroad?

The surveillance equipment pioneered in Xinjiang is being exported

Xinjiang officials spent $9 billion on surveillance equipment in 2017. The ubiquity of surveillance and techniques used was perhaps most comprehensively captured in the Wall Street Journal’s December 2017 report.

Reuters reported this month that a handheld scanner commonly used by police in Xinjiang, which can “break into smartphones and extract and analyze contact lists, photos, videos, social media posts and email,” was ordered by “police stations in almost every province” since 2016.

Adrian Zenz told BuzzFeed last year that Xinjiang is “a kind of frontline laboratory for surveillance… Because it’s a bit outside of the public eye, there can be more experimentation there.”

Some reports have also shown how Chinese surveillance technology is being exported abroad, including two pieces in Foreign Policy: “Ecuador’s all-seeing eye is made in China” and “Beijing’s Big Brother tech needs African faces.”

China is testing the world’s response to its human rights abuses, and so far, the response is underwhelming

Recent reports have indicated that the repression of Islam in Xinjiang is spreading to other parts of China, in particular neighboring Gansu. Agence France-Presse reports:

The Communist Party has banned minors under 16 from religious activity or study in Linxia, worrying many of the local Hui people. One senior imam reflected on the policies’ similarities to those in Xinjiang, stating, “Frankly, I’m very afraid they’re going to implement the Xinjiang model here.”

This makes the relative radio silence from Muslim countries all the more stunning.

- Central Asian countries neighboring Xinjiang have done little to speak out about the re-education camps, the scholar Gene Bunin writes: “Though people in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Pakistan all demand the reunification of their families and the safety of relatives in Xinjiang, their governments, despite not openly supporting China’s internal policies, still find themselves numb before an overwhelmingly powerful neighbor.”

- Bunin attributes the numbness to the fact that “much of these countries’ future development depends on China.”

- Another explanation for the silence: Uyghurs “are on the edge of the Muslim world, in contrast to the Palestinian cause, which is directly connected to the fate of one of Islam’s holiest cities, Jerusalem,” Nithin Coca says. With Xinjiang being remote, and access being limited, few photos and videos of oppression are published widely, so the world is slower to respond.

Jerome Cohen, one of the most authoritative scholars of Chinese law and a specialist in human rights in China, has recommended that “the U.S. Government adopt Magnitsky Act sanctions against those responsible for Xinjiang, starting with Xi Jinping.” In April, a U.S. State Department official said that the government was considering pursuing sanctions on officials involved in Xinjiang. Multiple scholars and civil society representatives in July urged the U.S. to sanction Chinese officials — in particular, Chen Quanguo 陈全国 — but so far, nothing.

I've been pretty surprised by how quiet the generally super outspoken China-watching academic community has been on this. I don't think self censorship is the only issue— perhaps it's also that we've all been conditioned to accept human rights abuses in China as normal.

— Megha Rajagopalan (@meghara) August 5, 2018

That’s not to say there’s not discussion. A debate has begun about how sinologists and academics who research China should respond to the enormous repression and social engineering under way in Xinjiang. Scholar Andrew Chubb has summarized the different arguments in a useful Twitter thread.

And then there’s this: Harassment and abuse of journalists reflects a broader trend

Globe and Mail China correspondent Nathan Vanderklippe was detained a year ago when he reported on Xinjiang.

Family relatives of four ethnic Uighur journalists, including three who are U.S. citizens, working for the U.S.-funded outlet Radio Free Asia, were “detained or have disappeared” in Xinjiang, the Washington Post reported in January 2018.

BuzzFeed journalist Megha Rajagopalan, who wrote essential reporting on Xinjiang that is cited countless times in this article, was recently forced to leave China after her journalism visa application was denied by authorities without an explanation.

As Joanna Chiu, a journalist and writer on China, notes, it is “part of a pattern of denying visa access to foreign correspondents who covered sensitive issues.”

China declined visa renewal to a Buzzfeed reporter who did brilliant work on #Xinjiang and surveillance tech, among many other important topics. While not technically expulsion, it’s part of a pattern of denying visa access to foreign correspondents who covered sensitive issues. https://t.co/gO8m4kpcqh

— Joanna Chiu (@joannachiu) August 22, 2018

To sum up, with every step toward more repression and more restriction on information, we are less likely to know the full extent of China’s human rights abuses. It’s remarkable we know as much as we do about Xinjiang, how fast the situation has deteriorated, and how little the world is doing about it.

Update 8/23/18: A few links to Financial Times reporting added; timeline of when construction of mass internment camps began highlighted and clarified.

NOTE: This article was originally titled “Chinas re-education camps for a million Muslims.” Although there may very well be a million people who are or have been detained, and above there is documentation that suggests a number as large as a million, we do not yet have verifiable numbers.