North Korea and Rex Tillerson’s muddled arguments in Beijing

Why Kim Jong-un won’t be persuaded.

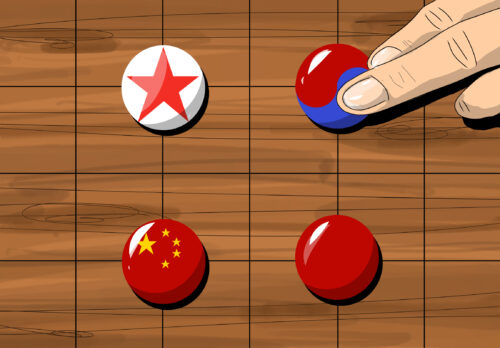

Throughout U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s controversial Asia trip, one issue dominated every conversation: What can be done about North Korea’s nuclear weapons? North Korea has vexed every American president since the end of the Cold War, so it comes as no surprise that the Trump administration thus far lacks a concrete plan to deal with Kim Jong-un and his growing arsenal. What was surprising, however, was the contradictory tone and content of Tillerson’s own messaging as he traveled from country to country.

In South Korea, Secretary Tillerson signaled a hard-line approach to the DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea). By rejecting what he called “the policy of strategic patience” and stating that the United States was prepared to take preemptive action if North Korea “elevate[d] the threat of their nuclear weapons program,” Tillerson alarmed foreign policy talking heads on Twitter and earned a rebuke from Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, who cautioned Washington to keep a “cool head” in dealings with North Korea.

But during the China leg of Secretary Tillerson’s Asia tour, the administration’s rhetoric had already softened. In an exclusive interview with Independent Journal Review’s Erin McPike, Tillerson declared,

Our objective is to have the regime in North Korea come to a conclusion that the reasons that they have felt they have had to develop nuclear weapons, those reasons are not well founded. We want to change that understanding. With that, we do believe that if North Korea [were to] stand down on this nuclear program, that is their quickest means to begin to develop their economy and to become a vibrant economy for the North Korean people.

On the face of it, this statement is agreeable to Chinese sensitivities — China has long desired North Korean economic reform — and hardly signals a break from Obama administration policy on North Korea. That said, are North Korea’s reasons for pursuing a nuclear weapons program “not well founded”? Is it possible to, in Tillerson’s words, change North Korea’s understanding?

The new administration would do well to consider that North Korea is a keen observer of American foreign policy globally, not merely in East Asia. And as it looks around the world, there’s a lot for Pyongyang to dislike. While discussing Tillerson’s remarks on North Korea, the New York Times reported that intelligence assessments by the Obama administration found

…that the example of what happened to Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi, the longtime leader of Libya, had played a critical role in North Korean thinking. Colonel Qaddafi gave up the components of Libya’s nuclear program in late 2003 — most of them were still in crates from Pakistan — in hopes of economic integration with the West. Eight years later, when the Arab Spring broke out, the United States and its European allies joined forces to depose Colonel Qaddafi, who was eventually found hiding in a ditch and executed by Libyan rebels.

Libya was, of course, a hot topic during the 2016 presidential campaign, with Secretary Clinton and then-candidate Donald Trump clashing repeatedly over the so-called Benghazi scandal, yet Secretary Clinton’s other policy recommendations in Libya largely escaped scrutiny. This extensive discussion by Foreign Policy on the aftermath of the Libya intervention is typical of commentary during the election. Simply put, no one in the U.S. foreign policy establishment was debating the wisdom of removing Colonel Qaddafi in 2011 after he had agreed to end his weapons programs in 2003.

Turn back the clock to 2003, however, and we find that President Bush lifted sanctions on Qaddafi while promising that the United States would act in “good faith” toward Libya. The administration explicitly linked the example of Saddam Hussein’s overthrow to Qaddafi’s future in Libya, and offered a path of normalization for Qaddafi’s regime. Moreover, Bush administration officials were quoted as saying that they hoped Libya would provide a model for other regimes to give up their weapons of mass destruction.

What, then, is that “model” as North Korea sees it? An enemy of the United States disarms, the United States offers modest gifts in the form of sanctions relief, but it still takes military action for regime change as soon as it has the right opportunity. North Korea is also cognizant of how the Libya case was, in international relations terms, a test of deterrence. The thinking goes that without weapons of mass destruction — its deterrence — Libya fell prey to better-armed powers like the United States and NATO.

In fact, Libya isn’t the only recent example of a country giving up its deterrence capabilities and then suffering militarily for it. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, newly independent Ukraine possessed several thousand nuclear weapons, up to 15 percent of the Soviet nuclear arsenal. Russia and the West persuaded Ukraine to surrender its weapons to Russia in 1992 in exchange for security guarantees that were formalized in 1994. At the time, political scientist John Mearsheimer called the disarmament of Ukraine a mistake and predicted Russo-Ukrainian territorial conflict over Crimea. Roughly 10 years later, Vladimir Putin proved Mearsheimer correct. And although Russia is a de facto ally of North Korea, Pyongyang no doubt senses a pattern.

Recent history teaches us that without an adequate deterrent, minor powers like the DPRK are vulnerable to the designs of great powers like the U.S. This brings us to a less-acknowledged perspective in East Asia: North Korea’s own security dilemma. How do the United States, China, and other relevant parties assuage Pyongyang’s fears, especially when the United States views North Korea as a rogue state?

One notable North Korea expert has recently argued that the DPRK will never feel secure unless it signs a peace treaty with the U.S. and then seizes control of South Korea. Whether or not Kim Jong-un subscribes to such extreme goals, his nuclear program provides the deterrent he believes he needs to sustain his regime for the foreseeable future. As such, while a denuclearized Korean peninsula might be in America’s and China’s interest, very little supports Secretary Tillerson’s assertion that denuclearization is in North Korea’s interest.