Venezuela-China, explained: The Belt and Road

This is the second of a four-part series, which will be published on Mondays this month, that spotlights the Venezuela-China relationship.

Part One: China’s choice to penetrate the Latin American market

Part Two: China, Venezuela, and the New Silk Road in between

Part Three: The geopolitics of the dragon in Little Venice

Part Four: China, a long-term partner for Venezuela?

Key points:

- In 2001, Venezuela became the first Hispanic country to enter into a “strategic development partnership” with China, a relationship that was elevated to “comprehensive strategic partnership” in 2014, and which now totals at least 790 investment projects in Venezuelan territory. They range from infrastructure, oil, and mining to light industry and assembly.

- China’s development projects in Venezuela have disappeared over the past 11 years, mostly devoured by corruption or by the debt default that the South American country has incurred with the Asian giant, which froze many direct investments.

- Loans from China to Venezuela reached at least $50 billion by 2017, with some estimating the number to have been as high as $60 billion. (The uncertainty regarding the figure is the result of opaque loans, split into payments of $2 billion and $5 billion each.)

- As of 2016, China has stopped issuing new loans to Venezuela. Since then, Chinese representatives have sought unofficial meetings with individual members of the opposition, trying to secure guarantees that the debt, about $20 billion, will eventually be paid back.

- In 2000, there was an immigrant population of approximately 60,000 Chinese in Venezuela. Eighteen years later, President Nicolás Maduro estimates there are 500,000 Chinese citizens residing in the country.

- Venezuela has gold reserves with a commercial value of more than $200 billion. In Coltan, reserves are valued at at least $100 billion, and iron is estimated at more than $180 billion. China worked with Venezuela on the Venezuelan Mining Map in an area of 111,800 square kilometers (12.2% of Venezuelan territory), and currently has direct investments of over $580 million.

PART TWO

China, Venezuela, and the New Silk Road connecting them

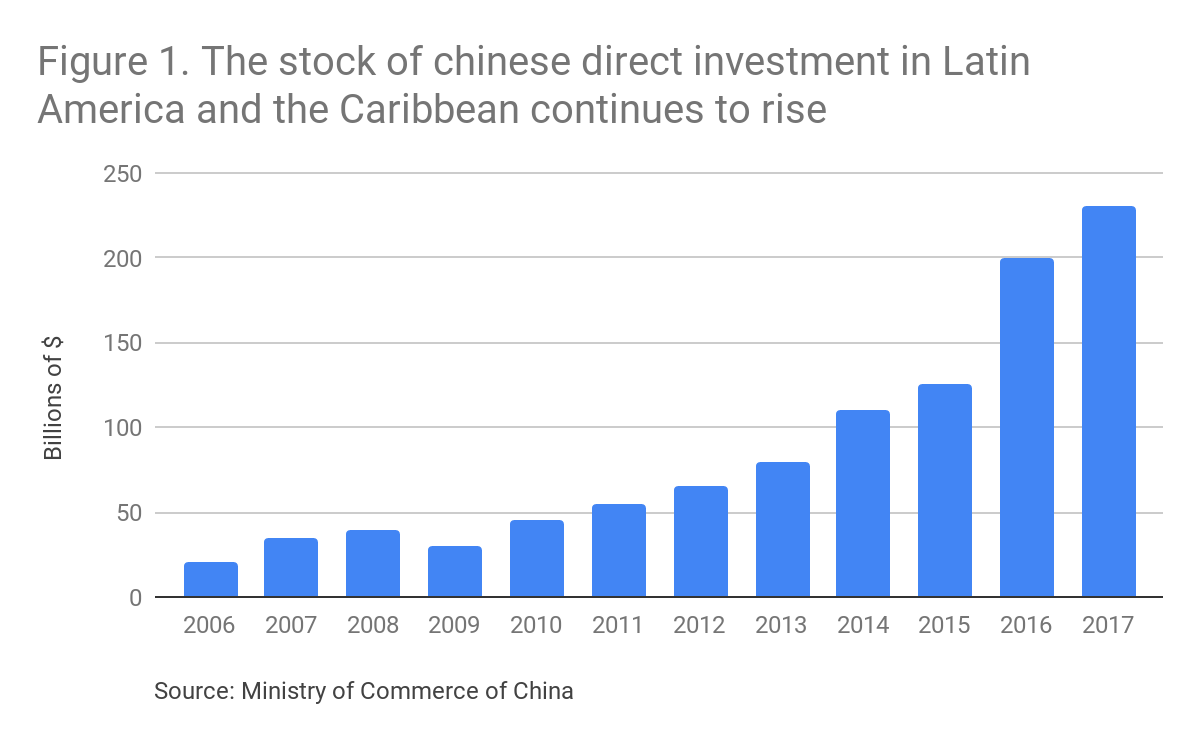

At the inaugural speech of the first ministerial meeting under the China-CELAC (Community of Latin American and Caribbean States) Forum in 2015, held in Beijing, Chinese president Xi Jinping 习近平 said that China’s purpose in Latin America was to increase commercial exchange with the region to $500 billion within the next 10 years, and direct investment to $250 billion. Three years later, at the second China-CELAC Forum in Chile (CELAC was formed in Venezuela in 2011, and does not include the U.S. or Canada), China’s foreign minister Wang Yi 王毅 reinforced Xi’s declaration, calling Latin American countries “a natural extension” of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Investments in China had not always been part of the Belt and Road Initiative — Xi’s grand political-economic project proposed in September 2013 that now counts more than 70 countries and affects 75 percent of the known energy reserves in the world — but they very much are today. Meanwhile, China has promised “conditions of equality,” even as the country has yet to make significant direct investments in Venezuela.

In September 2018, Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro traveled to China for the 16th meeting of the China-Venezuela high-level commission and was promised by Wang Yi that China would strengthen cooperation and bilateral relations with Venezuela through the Belt and Road. Unfortunately, details about exact agreements and numbers remain scant.

Although Venezuela has made political statements of support for Belt and Road, it has yet to sign any direct investment contracts (only more general “investment agreements”), unlike other Latin countries, including Panama (the first to sign), Bolivia, Antigua and Barbuda, Trinidad and Tobago, and Guyana. However, Chinese loan investments have expanded in Latin America, with a particular preference for investment in Venezuela. The Chinese Development Bank has lent $150 billion in the last 12 years to Latin America, of which at least a third was directed at Venezuela.

As for China, it is now close to reaching $250 billion in direct investments, Xi Jinping’s promise at the first China-CELAC Forum in 2015:

China is expected to actually sign direct investment deals of $260 billion — $10 billion more than Xi’s original promise — due to China’s demand for copper for its construction industry and iron for steel production (it is the world’s largest producer). But these agreements are marked by opacity and the numbers are difficult to verify.

A mining country on China’s strategic route

In 2012, China signed an agreement with Venezuela to develop the Venezuelan mining map. The president of CITIC Group, Chang Zhenming 常振明, was received directly by President Hugo Chávez. But journalistic investigations and details of this agreement — which contained sensitive (and secretive) information, including a map showing the richest spots on Venezuelan soil — disappeared from the archives of many Venezuelan media outlets.

One report, which survives only as a web cache, detailed a team of 352 Chinese engineers who were described as the “undisputed heads” of 425 Venezuelan geologists, technicians, and workers in 27 camps in 12 states of the country. CITIC divided the country into six parts to perform airborne geophysical prospecting, geochemical studies, research, and evaluation of mineral resources (with emphasis on Guayana and the Andes), and exploration and calculation of reserves of iron, gold, and bauxite (in Bolívar), phosphate (Táchira, Mérida, and Falcón), and copper (Táchira). The nationwide investigation estimated the contract’s “total area of work is 916,700 square kilometers.”

In 2016, China reached an agreement with Venezuela for the mining of coltan, the so-called “blue gold,” which is used to develop electronic materials ranging from smartphones to specialized medical equipment. The mineral reserves captured by China through these agreements were worth at least $100 billion, based on the value of reserves in 2010. This figure does not include subsequent discoveries.

On July 21, 2017, Venezuela and China signed an agreement worth $580 million for other mining activities. $400 million of this was earmarked for a strategic alliance with three major Chinese companies for the development and promotion of the Arco Minero del Orinoco (the Orinoco Mining Arc), along with updating the Venezuelan mining map.

These agreements have been extended in the Arco Minero del Orinoco project, conceived by Chávez and the flagship project of the current president, Maduro. It is an area of at least 111,800 square kilometers that corresponds to 12.2% of all Venezuelan territory, rich in strategic minerals such as iron, gold, bauxite, diamond, copper, coal, quartz, titanium, tin, nickel, and coltan, among many others.

Gold reserves in Venezuela represent a commercial value of more than $200 billion, while iron reserves have an estimated value of more than $180 billion. Both resources are coveted by China, which has the most gold on the planet.

But there is another material from Venezuelan soil that could be extremely valuable. Its name is torio (Thorium), and it has the potential of becoming an ecological nuclear fuel. Professor Eduardo Greaves, an expert in nuclear physics and a professor at Simón Bolívar University, pointed out that Venezuela has “a huge deposit” of Thorium in the Cerro Impacto in the southern state of Amazonas, which is part of the Orinoco Mining Arc, of which China knows all about, having directed the development of the geological and mining map of the Venezuelan territory. Greaves said these reserves could be used in thorium nuclear reactors for at least 300 years.

China has set its sights on this mineral, which can potentially become the green energy of the future. In addition, it and India were the first countries to have a Thorium reactor. China plans to use that reactor to build a pilot Thorium plant by 2020, with the hopes of replacing coal energy with nuclear energy.

In 2016, China planned to build at least 30 nuclear reactors in the next 15 years in countries that are part of the Belt and Road. They have 33 reactors currently in use and 22 under construction, according to data from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA); Thorium reactors are very much part of their strategy to replace fossil fuels in the future.

Recently, Maduro said that China will finance the growth of oil production in the country, but didn’t mention contracts in the mining area. “There are financial commitments for the growth of oil production, the growth of gold production, and investment in more than 500 development projects within Venezuela,” Maduro, in Beijing, told VTV, a Venezuelan state television station. He did not provide more details.

China has been pushing the Maduro government to maintain the flow of oil payments. Maduro promised on October 19, 2018 that it would increase oil exports to Beijing and Moscow so that they reach 1 million barrels per day, “rain or shine.” However, a source at the Venezuelan state oil company told a local newspaper that “the original agreements, which provide for the shipment of 600,000 and 300,000 barrels of oil per day to Moscow and Beijing, respectively, now barely reach 300,000 and 150,000 barrels.” Although the flow of payments has gone down, this has not weakened the relationship between China and Venezuela.

But the credit line is not the only big concern for China, which finds itself in the middle of a commercial war with Venezuela’s first partner: the United States. In next week’s installment, we’ll delve into the political implications of China’s dealings with Venezuela, and look at the corruption that has resulted.

Part One: China, Venezuela, and the New Silk Road between

Part Three: The geopolitics of the dragon in Little Venice

Part Four: China, a long-term partner for Venezuela?