Belt and Road interview: Scholar Dragan Pavlićević on BRI and China’s foreign policy

It’s been over five and a half years since Chinese President Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 first revealed the hugely ambitious idea of a “Silk Road Economic Belt” during his 2013 visit to Kazakhstan. Later reintroduced by the Chinese government as the “Belt and Road Initiative,” or BRI for short, the mammoth project is an undeniable game changer in the global geopolitical landscape. Since its launch, more than 80 countries — accounting for roughly two-thirds of the world’s population — have officially signed on to build infrastructure projects with China under the umbrella. Exact numbers on how much investment should be classified as “Belt and Road” investment are hard to calculate, but the total investment so far has reached hundreds of billions of dollars.

As the scope and reach of BRI projects has expanded, criticism and opposition in many countries has also increased. For developing countries participating in the project, Beijing’s loans for railroads, airports, and roads also come with a possibility of putting them at a high risk of debt distress. It’s reported that such concerns have caused a string of countries to cancel and walk away from previously committed BRI projects. Meanwhile, the initiative has also stoked some political concerns, as for some regions, a sudden influx of money has the potential to enable corruption and pose threats to local political ecosystems.

In search of answers to a host of questions we have regarding China’s continent-spanning venture, we recently spoke with Dr. Dragan Pavlićević, a lecturer in the Department of China Studies at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU) in Suzhou, China. Pavlićević has three China studies degrees under his belt: a bachelor’s degree from the University of Belgrade in Serbia, a master’s degree from Renmin University in Beijing, and a Ph.D. from the University of Nottingham. In recent years, he has written extensively on a range of China-related subjects that includes the politics of China’s overseas infrastructure projects, China-Europe relations, and China’s foreign policy.

This interview has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

The China Project: What are your main takeaways from the Belt and Road Forum 2019?

Pavlićević: I think there are three main takeaways.

First, it is clear that China remains committed to developing its foreign relations under the BRI framework, despite occasional speculation recently that there has been less interest in, reconsideration of, and even some degree of resistance to the initiative from within China.

Second, given the number and variety of countries and international organizations that had sent delegations to the Forum, and the number and variety of agreements that have been signed during the Forum, it is clear that BRI is a major initiative with a global outreach and significant impact, and internationally recognized as such. In that sense, the BRI Forum 2019 consolidates China’s position as a key actor and leader in a global context. Whatever the reservations and concerns there might be about BRI and despite a number of important international actors such as the U.S., India, and the EU refusing to endorse BRI, it is clear that China is today — in stark contrast to the period even immediately before the launch of BRI in 2013 — recognized in all corners of the globe as an actor that has to be reckoned and engaged with.

Third, the Forum’s focus on sustainable and green development, debt control, and “high-quality cooperation” shows that Beijing has been perceptive of the criticism leveled on BRI, and signals that it is willing to address these concerns.

The China Project: Some critics have blamed the initiative for heaping onerous debt onto participating countries. What’s your take on that?

Pavlićević: It appears to me that this dominant narrative oversimplifies the issue. Some recent research does suggest that it is “unlikely that BRI will be plagued with wide-scale debt sustainability problems,” and that China has often restructured and canceled debt. Some cases of debt restructuring have resulted in an outcome more favorable to the borrower, which also indicates that China’s leverage in negotiations is more limited than what critics usually thought. What is often missing in the debt-trap narrative is a better-informed discussion of China’s interests when it comes to BRI and, more specifically, loan giving. Rather than creating leverage for political influence, BRI and loan giving are better understood as a subsidy program for China’s economy. The function of China’s lending is to help Chinese enterprises access foreign markets and by doing so ensure new sources for growth of China’s economy. Therefore, tied loans (loans extended to another country of which the significant portion is to be spent on products and services from the lending country) are important elements of China’s BRI.

What is often missing in the debt-trap narrative is a better-informed discussion of China’s interests when it comes to BRI and, more specifically, loan giving. Rather than creating leverage for political influence, BRI and loan giving are better understood as a subsidy program for China’s economy.

Additionally, what is often forgotten is that debt that does not produce returns but accumulates losses is not viable long term for China, either. Moreover, projects that would create financial and political problems for host countries would put a stain on BRI and make it more difficult for China to further deepen exchange with others under BRI. It is not in China’s interest for this to happen, and for that reason, I believe that Beijing will consider how to balance outward expansion via BRI with its sustainability and that pledges that China will address the concerns about the debt unsustainability that have been aired during the Forum are credible.

The China Project: How would you characterize China’s success or setbacks in selling Belt and Road infrastructure investment in Europe? How does the perception of Belt and Road differ there compared with in Southeast Asia or other regions?

Pavlićević: China has been successful in infrastructure investments in those countries in Europe — in the Western Balkans in particular — that are outside of the EU. These countries are not bound by the EU legislation, which essentially prohibits state-to-state agreements and use of tied loans for public procurement projects, requiring a transparent and open bidding process instead. Such regulations, together with easier access to internal funds for the EU members, have prevented China from achieving the same success with infrastructure projects elsewhere in Europe.

That being said, the EU increasingly insists that non-EU members align their policies, including those related to government procurement and infrastructure development, with those of the EU as a condition to move forward toward gaining EU membership. This poses an obstacle for China.

I think that, generally speaking, there is less concern about China in Europe than in Southeast Asia. Simply, China is not geographically close enough to be perceived as the “big, fearsome neighbor” as it is in some quarters in Southeast Asia and it does not have a history of direct involvement in the regional politics. Also, for the majority of European countries, China’s participation in their economies is still not at a level that would cause concerns about overdependence on China. In fact, there is desire across the continent to further engage China in economic exchange and profit from it.

That being said, some of the major European countries and the EU establishment are very concerned about their relationship with China as well as whether China is building political capital and influence via BRI that would weaken their political and economic position in Europe and beyond. This is increasingly reflected on both a rhetorical and a policy level. For example, a leading EU official has defined China’s growing involvement in Europe as one of the great challenges of Europe. A recent communication from the European Commission on EU-China relations labels China a “systemic rival.” A recent discussion paper calls for more state involvement and protectionist measures to maintain Europe’s edge in the face of China’s state-supported and rapidly increasing competitiveness in key industries. With China in mind, many of the big European economies have tightened their foreign investment screening regimes, while the EU has endorsed the common framework, which has officially entered into force on 10 April 2019.

How these competing logics — of wanting to engage China for the sake of economic benefits it would bring, on the one hand, while at the same time protecting the political status quo in Europe and the competitiveness of major European economies, addressing security concerns, and balancing the trans-Atlantic relationship, on the other hand — will eventually shape the relationship is anyone’s guess at the moment.

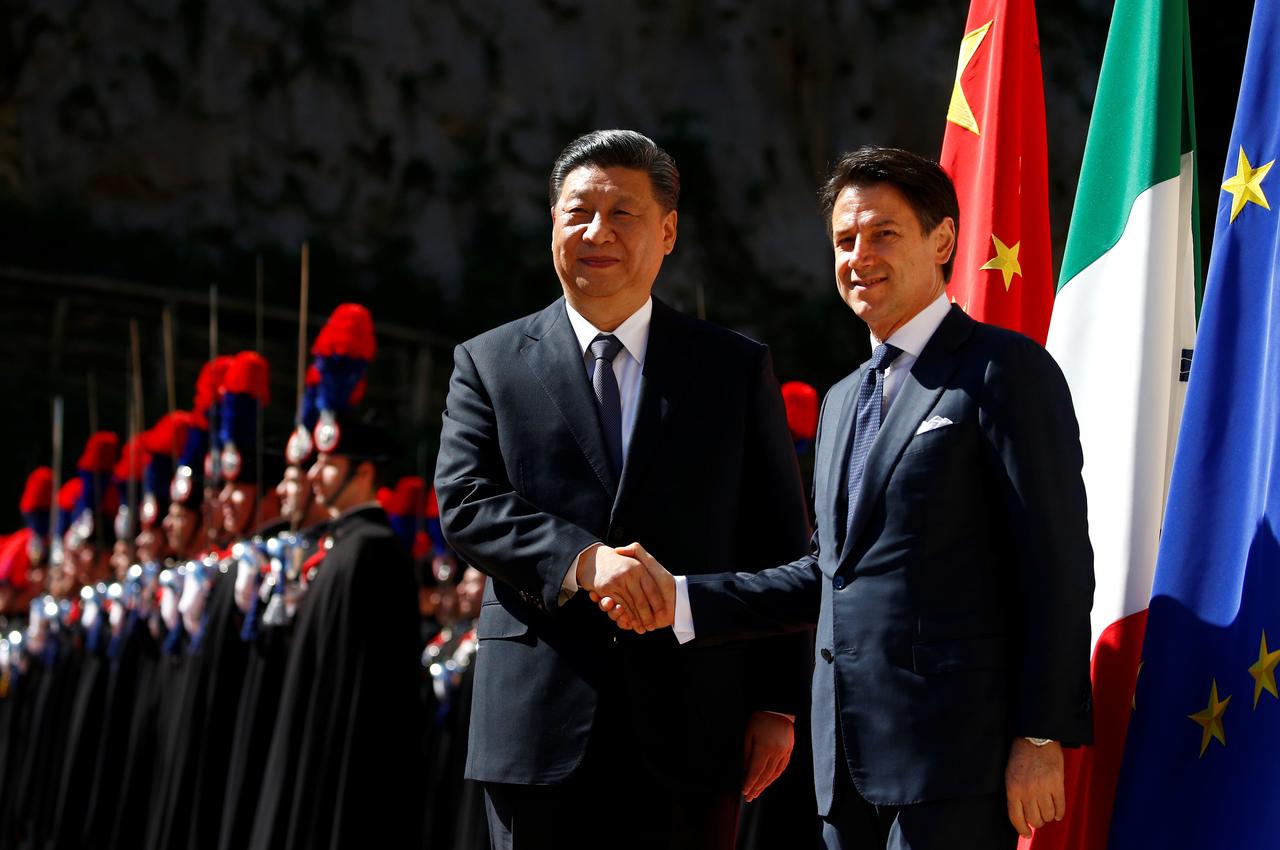

The China Project: What is your view on the Italian government’s decision in March to sign a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with China to allow Belt and Road investment, particularly at its shipping ports? Are other European countries likely to follow?

Pavlićević: I think this could be explained by Italy’s efforts to support the economy, which has been going through tough times, and to catch up in terms of its exchange with China with other major Western European countries. Also, apart from these structural reasons that would inevitably sooner or later drive Italy to explore ways to deepen a relationship with China, Italy’s current undersecretary of state in charge of international trade and foreign investment is a China specialist, and I would think that this MOU is also to a great extent about his own personal efforts.

MOUs merely signal an intention to explore ways to cooperate and develop relationships. But MOUs eventually need to be filled in with content. Signing MOUs is easy, but identifying opportunities that appeal to both sides, and the models of cooperation that appeal to both sides, is much more difficult.

How important is this? What has received less attention is that in the following days Switzerland and Luxembourg also signed BRI MOUs. This will create competitive pressure on other Western European countries to sign up for BRI as well. The same has happened with regards to the membership of European countries in AIIB [the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank], where after the initial reluctance once the first European country applied for membership, an avalanche of applications from other European countries ensued. In the near future, we will probably see other Western European countries signing BRI MOUs with China.

At the same time, I would be careful not to overstate the importance of signing the MOUs. MOUs merely signal an intention to explore ways to cooperate and develop relationships. But MOUs eventually need to be filled in with content. Signing MOUs is easy, but identifying opportunities that appeal to both sides, and the models of cooperation that appeal to both sides, is much more difficult.

The China Project: Is Serbia really “China’s open door to the Balkans,” as an article in The Diplomat argued early this year?

Pavlićević: Serbia’s economic relationship with China is the most substantial one among the Balkan countries, given the value of joint infrastructure projects (over USD$9 billion) and a number of strategically important investments in the Serbian economy made by Chinese enterprises in recent years. It also develops within a sound bilateral relationship, where China is perceived by Serbia as an important international partner and vice versa. Serbia is also an active participant in the China-led so-called 16+1 multilateral format. This has led even the EU officials to voice their concerns about Serbia and, more broadly, about the Balkans being Trojan horses where China’s growing influence will weaken the regional status and possibly even the coherence of the EU.

However, China’s relationships with the Western European countries are by the same standards much more developed. The economies of the major Western European states are to a much higher degree interdependent with China’s, while there are tens of EU-China-level dialogues and exchange mechanisms. And, given their political and economic weight, relationships with Western European countries and the EU are comparatively more important to China than those with Serbia and the Balkans.

More importantly, Serbia and other Balkan states are all strategically oriented toward gaining the EU membership. Looking at their trade and investment relationships, the EU dominates the trade and FDI stock flows of these countries to the amount of anywhere between 60 percent and 90 percent of the total. These provide the EU with a leverage over Serbia and the Balkans. In recent years, the EU has moved to strengthen its position in the Balkans, and has through informal and formal, rhetorical and policy means pushed the Balkans to align their policies, including toward China, with those of the EU.

The China Project: You’ve written multiple times on competition between Japan and China in international high-speed rail contracts in Southeast Asia. What is the public perception of Japanese-built vs. Chinese-built high-speed rail in Indonesia or Thailand, for example, and is it very different from the government’s perception of who is the better partner? Why does China generally win these contracts?

Pavlićević: I have not specifically researched the popular perceptions of Chinese and Japanese projects in Southeast Asia (SEA). But it is reasonable to conclude that the fact that the governments in SEA countries are interested in pushing forward these projects suggests that these projects are generally welcome by the electorate — that is, the local population — regardless of whether they are delivered by Japan or China.

The relative success of China’s efforts to export railway projects to SEA comes down to a combination of several factors.

First, China offers competitive technology, competitive prices, substantial financial support, and, in general, shorter times of delivery than its competitors.

Second, China has shown a high degree of flexibility in the negotiation of these projects, revising their technical specifications, price tag, and various other aspects of the projects so as to make them more attractive to the host countries and better aligned with the host countries’ preferences.

Third, China tends to offer add-ons, such as residential and commercial real estate development projects around the rail lines, other investments, and transfers of know-how, which make these projects more attractive to host countries.