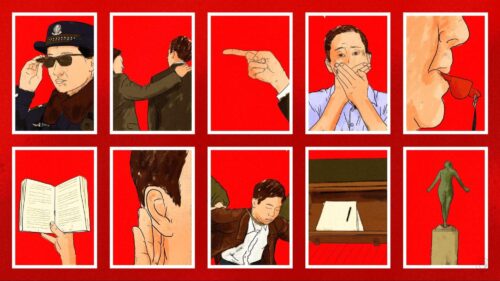

Inside China’s ever-evolving censorship apparatus

Like many things within China, the country’s notorious censorship system is opaque. Below, we describe the organizations that have the power to control what is published and broadcast in the People’s Republic, and how they communicate their demands.

Like many things within China, the country’s notorious censorship system is opaque. The government describes censorship with euphemisms like “content management” but they do not publish a list of rules or procedures, nor is there even one single government body responsible for it.

Below we describe the organizations that have the power to control what is published and broadcast in the People’s Republic, and how they communicate their demands.

China’s control of its mass media is unique, but built on the Soviet model

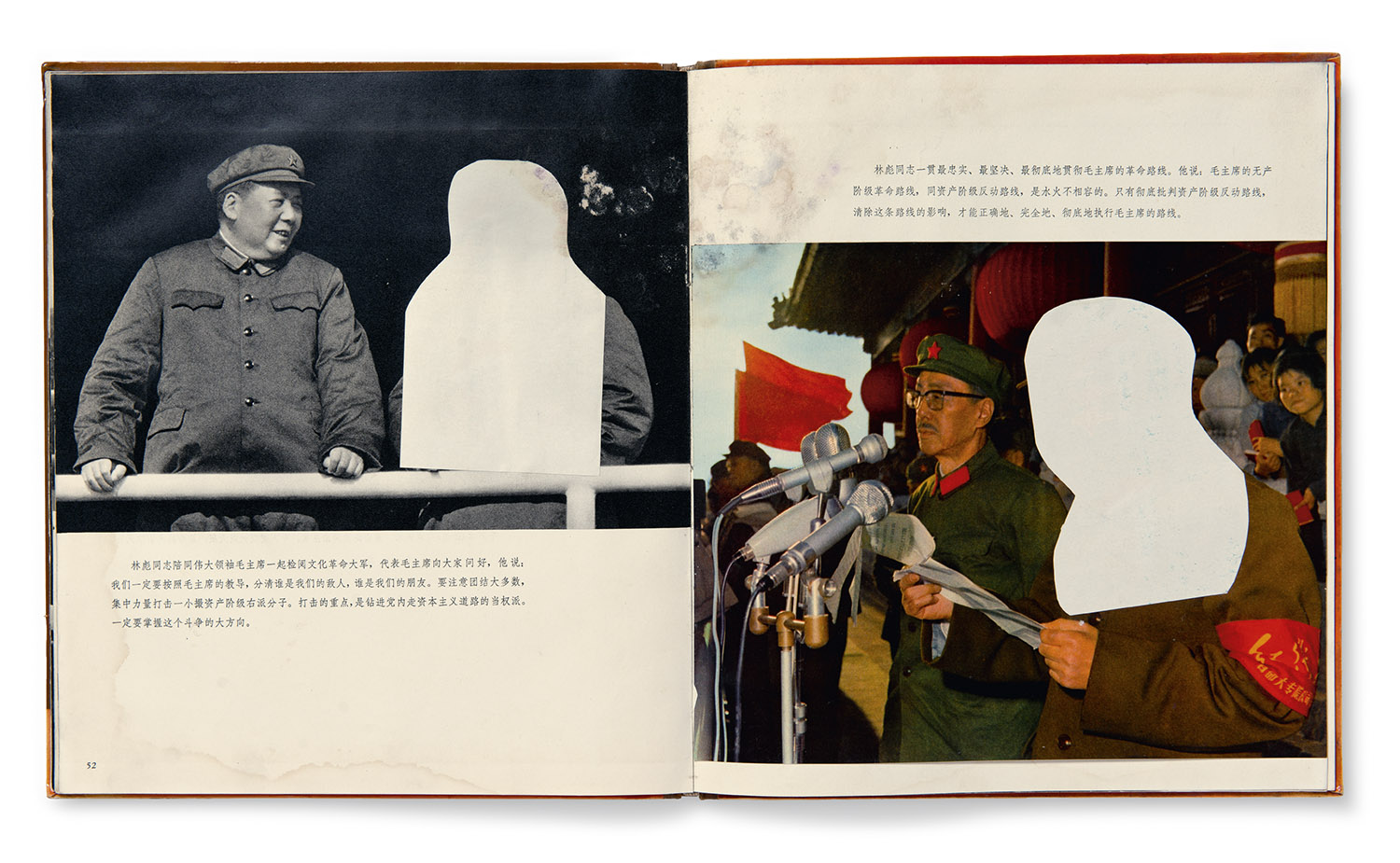

In the early years of the People’s Republic, the Communist Party copied the Soviet model to manage media. At its core, the Party state’s approach to organizing and controlling media was aggressively imposing checks along every step of content creation. Every single means of production and distribution — printing presses, recording studios, newspapers, books, radio stations, you name it — were all overseen by the Party, which served for the sole purpose of promoting information approved by the officials. Writers, editors, and broadcasters were explicitly agents of the CCP.

In the 1980s, China slowly began to allow commercial, privately-controlled media. Starting with film and music, the Party loosened its grip little by little, eventually allowing a certain degree of independence in the production of books, magazines, newspapers, TV programming, and later the internet. However, the government didn’t completely abandon the old Soviet-style tools of control.

The regulatory and administrative complexity of China’s censorship machine

There is no single government department that handles censorship in China. Rather, a complex and confusing web of departments implement censorship of different types of media, all with their own constantly changing priorities and organizational quirks.Prepare to get lost in a sea of acronyms. Here are the most important government departments, and how their roles in censorship have changed in recent years:

- The Publicity Department of the Communist Party of China, formerly known as the Propaganda Department, takes the lead in deciding what is kosher and what is forbidden and setting direction for media and state messaging for the whole country.

- The State Council Information Office (SCIO) has a parallel function to the publicity department, but it is officially controlled by the government, not the Party.

- The Ministry of Public Security (MPS) controls technical internet censorship, and like the Ministry of State Security (MSS), also has powers to shut down websites and printing presses.

- The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) is the most important regulator of internet content, and has become much more powerful under the Xi Jinping administration.

- The National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA) oversees licenses for news publishing, books and periodicals, radio, film, TV, and video game software. Before March 2018, it was known as the State Administration of Press, Publication, Film, Radio, and Television (SAPPFRT), which in turn was formed in 2013 by a merging of the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) and the General Administration of Press and Publication (GAPP).

- The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) shares — and sometimes fights over — responsibility for regulating internet and video media. MIIT controls networks and the internet, but more from a technical side.

- The Ministry of Culture and Tourism (MCT) oversees theater, live music, visual arts, potentially all “cultural products,” and also has oversight over video game hardware.

The organizations listed above issue instructions to news organizations and internet companies by telephone and in writing on a regular basis. China Digital Times publishes leaked and translated versions of these censorship instructions: Directives from the Ministry of Truth.

However, the most important type of censorship is self-censorship: writers, editors, musicians, social media users, filmmakers and the organizations that employ them do not want to lose their operating licenses or get in trouble with any of the regulators mentioned above.

Censorship in the age of the internet (GFW & VPN)

From the earliest days of China’s internet, the government worried about information from abroad flowing into China. In a 1997 article for Wired magazine, Geremie Barmé and Sang Ye coined the term Great Firewall (often shortened to GFW) to describe a system of filters and blocks that could cut off access to foreign websites and web pages.

With more than 800 million Chinese people now using the internet and the rise of social media that allows anyone to be a publisher, the Great Firewall has greatly expanded. Most major western news websites and all major foreign social media services are blocked, along with thousands of websites that are deemed objectionable.

To get around the firewall, one can use a virtual private network (VPN) service, which can be easily installed on digital devices and encrypts one’s internet connection by masking their IP address. Perfectly aware of the existence of such tools, the government has initiated a number of crackdowns that successfully interrupt VPN services from time to time. Of a VPN crackdown in early 2018, Lucy Hornby, the Beijing deputy bureau chief for the Financial Times, argued that the government’s motivation was “about money as much as censorship” (paywall):

Censorship aside, the move is a classic case of rent-seeking by a regulator eager for the licence fees that come from forcing everyone to use favoured companies — in this case the telecoms triopoly and the dozen or so companies authorised to sell VPNs.

The Great Firewall is operated under the “Golden Shield Project” by the Bureau of Public Information and Network Security Supervision, which is controlled by the Ministry of Public Security.

Chinese tech giants and media companies are turning self-censorship into a business

In the past decade, the boom of internet-based business has created novel opportunities for Chinese tech giants and established newspapers. Newspapers that have been around for many years, such as the People’s Daily, have been refashioning themselves as online publishers and using social media platforms to distribute content. Meanwhile, major players in China’s tech sector, such as Tencent and Baidu, have recruited reporters and developed their own content services.

The immense amount of information that appears on their platforms every day, however, also poses a censorship challenge: companies need to make sure they don’t get into trouble because of content from their employees or users. They do this using software, but also huge numbers of people. ByteDance, the Beijing-based company behind the hit video app TikTok, currently has six offices across the country dedicated to what it calls “content quality control.” In August 2018, to reduce the investment on human labor in the long run, ByteDance built a research center in Nanjing, where hundreds of computer engineers specialized in machine learning are working together to bring self-censorship to the next level.

The demand for self-censorship is so high that it has turned into a profitable business. In Jinan, Shandong Province, which is seen as an up-and-coming capital of internet censorship, there is an entire office building dedicated to hosting self-censorship units. The city is also home to an information technology company affiliated with People.cn, the internet arm of the People’s Daily. As noted by local newspapers, the firm was designed to cultivate a grand army of internet censors who can be deployed, for a fee, to any internet company.

Further reading

- “The connection has been reset” by James Fallows

- Behind the Great Firewall and China’s internet – a civilising process by Jeremy Goldkorn

- The crystal-clear waters of the Chinese internet by Jeremy Goldkorn and Lorand Laskai

- Internet censorship in China on Wikipedia

- The Great Firewall by Sang Ye and Geremie Barmé