Diplomats and state media screech on Twitter as China loses friends

As far back as 2009, it has been noticeable that Chinese diplomats and government spokespeople have taken a more aggressive line against international criticism. But in the last couple of years, the tone has got a lot sharper.

Two recent examples:

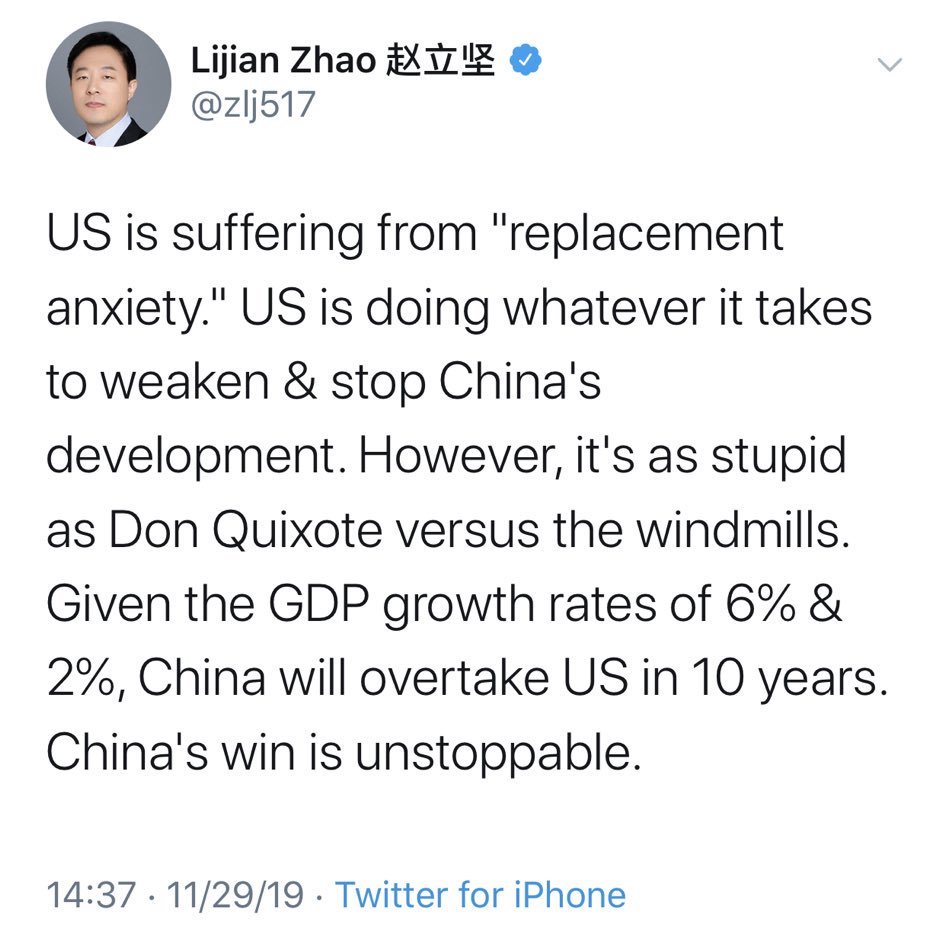

Zhào Lìjiān 赵立坚, a diplomat who cut his Twitter teeth as the second-ranking official at China’s Pakistan mission, was rewarded for his diatribes with a promotion (although this weekend, even he felt it necessary to delete a tweet saying China would “win” against the U.S. — see above, a screenshot of the deleted tweet captured by Bill Bishop).

(Our managing editor Anthony Tao, prompted by a series of Zhao’s tweets in July, wrote this about him at that time: “It truly is a special way to see the world, requiring a form of willful small-mindedness that intelligent human beings should be ashamed of.”)

Kǒng Línlín 孔琳琳, an employee of state broadcaster CGTN in London, was supported by state media for exercising her “freedom of expression” after she was convicted of common assault there for slapping a Conservative delegate at a political conference.

The Chinese embassy in the UK Sat expressed shock and indignation toward a UK court ruling which found Chinese reporter Kong Linlin, guilty of common assault. The ruling raises doubt on UK's judicial credibility and its claimed advocacy for free speech and press freedom: embassy pic.twitter.com/yCmbZ9XEdp

— China Daily (@ChinaDaily) November 30, 2019

There are dozens of similar examples of China’s new, in-your-face style of diplomacy, from the remarks of the undiplomatic Chinese ambassadors to Sweden and to Italy, to envoys from Beijing storming out of a forum for Pacific islands. But if the idea is to win friends and influence people, the strategy seems to be failing. Some of the evidence of that failure from today’s news:

In Australia, from the Sydney Morning Herald:

A year ago, most Australians trusted China to act responsibly. No longer. The proportion of people trusting in China fell from 52 percent to 32 in a year, according to the annual Lowy survey.

More specifically, seven in 10 people say there is too much Chinese investment in Australia. That Australia is too dependent economically on China. That Australia should do more to restrict China’s military activities in the region — even if it comes at an economic cost. Six in 10 say they favour Australia’s navy conducting freedom-of-navigation exercises in the South China Sea.

See also:

- Suddenly, the Chinese threat to Australia seems very real / NYT (porous paywall)

- Torture fears grow for Australian writer shackled and isolated in a Chinese jail / ABC

In Canada, a November survey from the University of British Columbia (UBC) showed that China is now viewed favorably by only 29 percent of Canadians, down from 36 percent two years ago.

See also:

- ‘They’re that fearful’: Why this B.C. mayor is talking about the harassment of Chinese Canadians in Metro Vancouver / The Star

- B.C. politician breaks silence: China detained me, is interfering ‘in our democracy’ / Global News

In Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, anti-China sentiment “is emerging in anger, protest — and violence,” according to Alexander Kruglov.

Angst is fueled by multiple issues: unfulfilled hopes, debt traps, excessive deployment of Chinese capital and labor and a belief that Beijing is prioritizing its own interests.

Yet another bone of contention was Beijing’s treatment of its Muslim minority in Xinjiang — a minority many Central Asians feel an ethnic and religious kinship with.