Will COVID-19 forge a new generation of gritty Chinese entrepreneurs?

Will a generation of Chinese businesspeople, hardened by the economic and social shocks of COVID-19, change the way business is done in China? New research suggests that some Chinese entrepreneurs may emerge from the crisis with new experiences that will propel them to later success.

The COVID-19 pandemic has become a global crisis that could last for years, and is frequently compared with the 1918 influenza pandemic, which killed 17 million to 50 million globally. Social scientists have mostly shown negative long-term consequences of that pandemic on individuals who lived through it, such as reduced educational attainment, increased rates of physical disability, poorer health, and lower socioeconomic status. But our research on Chinese entrepreneurs uncovers that some hardship experiences can have positive effects, leading individuals to be more prudent and creative in using limited resources. While not discounting that there are significant negative effects of crises, this is consistent with other research on how experiencing negative events can have potential silver linings. For instance, a recent finance study shows that early-life exposure to natural disasters might make CEOs better able to deal with risk, citing Steve Jobs and Tim Cook as examples. In our research, we specifically look at how experiencing China’s Great Leap Forward famine (1959–1961, henceforth, the “Great Famine”) had some lasting positive effects on entrepreneurs.

From fruit vendor to global king of auto glass

Cáo Déwàng 曹德旺, the chairman of Fuyao Group, the large glass-making company featured in the Oscar-winning documentary American Factory, reflects in his autobiography that the Great Leap Forward famine made him stronger and more creative in solving problems. Cao was born in 1946 and forced to drop out of school in 1960 because of the famine. He helped his father sell pipe tobacco but could not continue, as the Cultural Revolution, which started in 1966, prohibited such business. Cao then switched to selling fruit. He recalled that every day he had to get up at 3 a.m. and carry 300 pounds of fruits to sell at a market tens of miles away from home. In the summer, he had to stay out in extreme heat and could not return home until late at night.

Through such hard experiences, Cao gradually saved about $19,000 by 1976 and acquired a state-owned glass factory that had experienced seven years of significant losses. After turning it profitable, Cao transformed his glass factory into an auto-glass maker by repurposing his existing facilities. He also actively invited international investors to help him sell his products in Hong Kong and the U.S. Today, with more than 10,000 workers around the world, Cao’s firm, Fuyao Glass, is valued at about $10 billion, including the U.S. subsidiary in Ohio featured in American Factory.

His experience is consistent with our statistical analysis of a database of Chinese entrepreneurs that shows that living through the Great Leap Forward famine may have provided Chinese entrepreneurs with advantages that can lead to future success, including better and more efficient utilization of resources. As another example, Zōng Qìnghòu 宗庆后, the founder of China’s largest beverage manufacturer, Hangzhou Wahaha Group, lived through the famine and credits the experience with his focus on cost reduction, which was key to the company’s development. For instance, as he recalled (in Chinese), the Great Famine led him to be resilient and frugal. Many other successful Chinese entrepreneurs also attribute some of their success to their experiences living through the Great Famine, including Rén Zhèngfēi 任正非 of Huawei, and Wáng Shí 王石 of China Vanke, one of the country’s biggest property developers (links in Chinese).

Cutting costs and saving money — lessons from the school of hard knocks

Accounts from entrepreneurs and our analysis suggest that famine experience might lead to future business success by inculcating two important qualities for entrepreneurs to use resources more efficiently: cutting down costs and repurposing seemingly useless resources.

During famine periods, individuals cannot afford to waste any resources, since the consequences could be dire. Further coloring individuals’ experiences during this period, an ideological principle underlying the Great Leap Forward was frugality. For example, Chairman Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 maintained that “frugality is one of the fundamental principles of the socialist economy” and a sub-movement during the Great Leap Forward was called “Enhance production with frugality” (in Chinese). Exercising such practices and being exposed to related propaganda likely affected individuals’ behavioral patterns and cognition. A similar idea has also been shown in the U.S. context — that individuals living through hardship are more focused on cost reduction.

In other words, by experiencing the Great Famine, individuals internalized frugal ways to deal with resources that may have become lasting characteristics. Many Chinese entrepreneurs have articulated (in Chinese) the relationship between their early resource experiences and their intense focus on cost reduction. For instance, Liú Yǒnghǎo 刘永好, born in 1951 — founder of the agricultural products company New Hope Group, which has a market value of $17 billion — is known for his frugality, typically spending less than one dollar for a haircut and eating with his employees in the company’s inexpensive dining halls. In his authorized biography (in Chinese), he recalls that the Great Famine experience made him cautious and prudent, and states that his resulting focus on cost management was one of his keys to his later success.

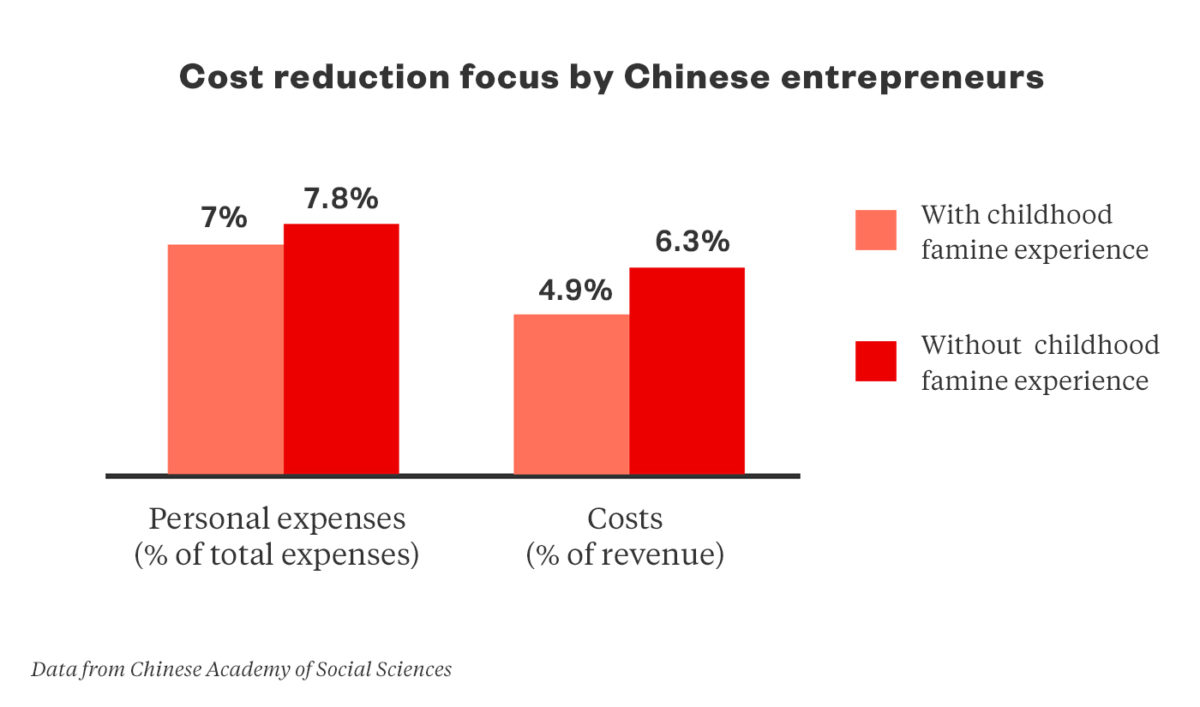

There are many other examples, such as Chén Ruìfèng 陈瑞凤, the founder of Deyang Digital Mechanics, who experienced the Great Famine and thereafter maintained very frugal habits despite her wealth. Our analysis of a database of Chinese entrepreneurs found that those who had experienced the Great Famine during their early childhood spent 10% less of their venture’s income on personal expenses and had 22% lower sales costs than those of average entrepreneurs, which adds up to around $8,600 and $15,000 respectively, substantial amounts for new ventures in China.

How to repurpose resources

Compared with cost reduction, repurposing is a more indirect method of utilizing resources efficiently. To stay alive during the periods we examine, Chinese residents were forced to repurpose available resources designed for other purposes. During the Great Famine, some people boiled belts and other leather belongings that seemed edible, trying to prevent their family members from dying. By repeatedly exercising such repurposing during the famine period, individuals tended to develop an ability to transform waste products to serve new, more profitable ends.

There is ample anecdotal evidence (in Chinese) that Chinese entrepreneurs who experienced the famine developed skills in repurposing existing resources. For instance, Lǔ Guànqiú 鲁冠球, the late founder and chairman of Wanxiang Group, a large auto parts conglomerate, was known for finding new, useful ends for discarded materials. Lu started his company by making products for automotive use from scrapped tractor parts and agricultural machine tools. He recalled (in Chinese) that “because of the resource scarcity during the Great Famine, I learned to manufacture treasure from existing scraps.”

Entrepreneurs with famine experience don’t just reuse materials; they are also likely to repurpose investment. Our analysis shows that entrepreneurs who went through more severe resource scarcity during the Great Famine in early childhood are 21.8% more likely to repurpose the foreign venture capital they receive, intended for domestic expansion, for later international market expansion.

In conclusion, our research suggests that experiencing the Great Leap Forward famine endowed those who experienced it with a mindset that focuses on more efficient resource use: cost reduction and resource repurposing, which are useful in dealing with challenging later situations. We in no way mean to discount the severity of the Great Famine or the COVID-19 pandemic, or dismiss the tragic human toll from both of these events. Also, we recognize that COVID-19 and the Great Famine are not perfectly comparable. But we suggest that lasting effects of disasters and crises on human populations are complex. For example, in line with our discussion, others have pointed out that some of the most creative companies of the last decade were founded during the 2008 financial crisis. With prior examples in history as our guides, even devastating tragedies can lead to some positive outcomes — as the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche said, “What does not kill you makes you stronger.”

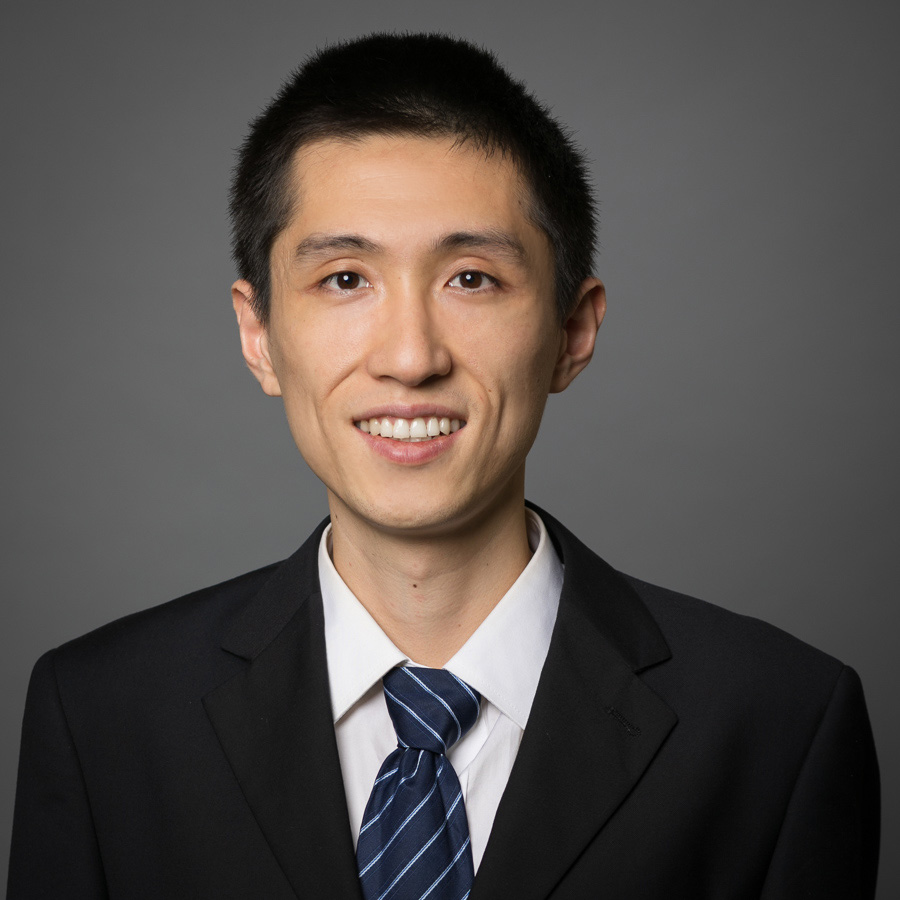

A closer look: Chinese entrepreneurs

Cáo Déwàng 曹德旺

Born: 1946, Fuqing, Fujian Province.

How he spent in his youth: Forced out of school at age 14. Worked as a laborer, street vendor, and bicycle mechanic.

Company: Fuyao Group, an automotive glass manufacturer featured in the Oscar-winning documentary American Factory.

What he’s famous for: Was named 2009 Ernst & Young World Entrepreneur of the Year, and is one of China’s biggest philanthropists.

Zōng Qìnghòu 宗庆后

Born: 1945, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province.

How he spent his youth: Dropped out of school after junior high in order to support his family. He first worked at a salt farm in Zhoushan and later a tea farm in Shaoxing.

Company: Hangzhou Wahaha Group (beverage manufacturer)

What he’s famous for: Named China’s richest man by the Hurun Report in 2012.

Rén Zhèngfēi 任正非

Born: 1944, Zhenning, Guizhou Province

How he spent his youth: Attended Chongqing Institute of Construction Engineering (now Chongqing University) and then worked as a military technologist in the PLA’s Information Technology research unit. Ren was barred from joining the Communist Party for most of his time in the military due to his parents’ ties to the Kuomintang.

Company: Huawei Technologies

What he’s famous for: Founding Huawei, the world’s largest manufacturer of telecommunications equipment and the second-largest manufacturer of smartphones.

Wáng Shí 王石

Born: 1951, Liuzhou, Guangxi Province

How he spent his youth: At age 17, he joined the army to work as a vehicle technician in Xinjiang.

Company: China Vanke, the largest real estate enterprise in China and the largest residential real estate developer in the world

What he’s famous for: In 2004, he co-founded the Society of Entrepreneurs and Ecology. Wang himself loves the outdoors. He has climbed the highest mountains on all seven continents and summited Mount Everest for the second time at age 60. He is also the president of the Asian Rowing Association.

Liú Yǒnghǎo 刘永好

Born: 1951, Chengdu, Sichuan Province

How he spent his youth: Member of the Red Guard, worked in Gujia Village on the outskirts of Chengdu. Was inspired to fully commit to the Communist Party after he met Chairman Mao in 1966.

Company: New Hope, the largest animal feed producer in China; vice-chairman of China Minsheng Bank (1995-2006)

What he’s famous for: Being the “richest chicken farmer” in China (a reference to his humble beginnings). In 1982, Liu and his three brothers sold their watches and bicycles to breed chickens and quails — a business that would eventually become New Hope.

Chén Ruìfèng 陈瑞凤

Born: 1944, location unknown

How she spent youth: Due to famine and poverty, in 1953, 9-year-old Chen’s family sold her to fellow villagers for 80 yuan ($11). She started working at the age of 10 — babysitting, selling tofu, working as a barefoot doctor. She married at 18 and raised three children on her own. Company: Putian Fuxin Mopei Computer Numerical Control Company

What she’s famous for: Starting her own business at age 52.

Lǔ Guànqiú 鲁冠球

Born: 1945, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province

Died: October 2017

How he spent his youth: Born to a peasant family. Dropped out of school at age 15 to become an ironsmith. In July 1969, he led six other farmers in raising 4,000 yuan ($570) to found the Ningwei Commune Agricultural Machinery Factory, which is now one of China’s 520 key enterprises (户重点企业).

Company: Wanxiang Group (automotive industry)

What he’s famous for: Leading the Wanxiang Group through the acquisition of over 40 overseas companies.