Grappling with my Chinese roots

A Chinese adoptee who grew up in Maine reflects on her difficult road to embracing her identity.

I used to hate China.

Growing up as a Chinese adoptee in the state of Maine, I felt like an outsider. I had a constant need to prove my whiteness and conceal all other aspects of my identity. I avoided wearing the color red, and I refused to tell people my Chinese middle name. Sometimes I would raise my voice in public spaces so that anyone passing by would know I spoke English fluently.

My goal was to blend in. But sometimes, just when I thought I was succeeding, someone would suddenly ask: “So where are you really from?” People were curious to know if I knew who my “real parents” were. A kid at a summer camp once asked me, “Why do your eyes look like that?” Some were shocked to learn that I couldn’t speak Chinese, while others would mockingly spout gibberish at me.

As a kid, I did not have the language to express my frustration with these remarks. I knew how they made me feel, but I did not know what to do about these feelings. I usually just absorbed them, assuming that microaggressions and racism were parts of life that I needed to get used to.

I was ashamed of who I was in part because I was surrounded by people who didn’t look like me or share my experiences. Most other kids knew when their own birthdays were and could fill out the medical history section of the form at the doctor’s office. I still don’t know the exact day that I was born or the name I was called for the first few months of my life. The other kids had no idea what it was like to be a Chinese adoptee in a small New England town. Not even my parents could understand these two central pieces of my identity.

All of these factors contributed to my hatred toward China. Years later, I would realize that these feelings were misplaced. I didn’t hate China, I hated how it felt to be Chinese in a white town. I hated being a hypervisible outsider in the place I considered home. I hated how my understanding of what it meant to be Chinese was shaped by people who didn’t have any idea what this meant.

During a time of heightened anti-Asian racism in the United States, I continue to hear stories about Asians and Asian Americans being verbally and physically harassed and attacked in public spaces. At any moment, my own reality could become one of these stories. At an earlier time in my life, this rising hatred toward Asian people would have prompted me to further distance myself from my Chinese identity and work toward convincing myself and others of my Americanness. However, over the past few years, I’ve had a chance to more deeply explore what it means to be a Chinese adoptee, leading me to accept aspects of my identity that I had previously tried to reject.

I didn’t hate China, I hated how it felt to be Chinese in a white town. I hated being a hypervisible outsider in the place I considered home.

In the spring of 2016, I returned to China for the first time since being adopted. Over the course of three months, I traveled through six provinces with a group of 11 other American students. As we made our way from the mountainous terrain of Yunnan to the bustling streets of Beijing, I began to develop an understanding of a country that I had long been fed false ideas about.

When passing through densely populated spaces, my group mates often attracted a lot of attention. People turned their heads to stare at and snap pictures of the foreigners with big hiking backpacks. For most of the students I was with, this heightened visibility was a less familiar experience. Just as they were all realizing what it was like to stand out, I, for the first time, was experiencing what it felt like to blend in.

One day early in our travels, I took a walk to a nearby park alone. I passed parents corralling their children and vendors selling cotton candy, and suddenly I realized that no one seemed to see me. For the first time in my life, I was surrounded by people who looked like me. I became just another person out for a walk in the park. For once, I did not stand out, but at the same time, I had never felt more like an outsider. This sudden invisibility was accompanied by a startling realization of my own Americanness.

This invisibility had its limits. All I had to do was open my mouth and it was strikingly obvious that I did not really belong. Anytime I spoke, I could see the puzzled looks in people’s eyes. The sounds coming out of my mouth did not match their expectations. Luckily, I had memorized a few phrases that usually helped to clear up the confusion. When people heard the words “American student…who was adopted” (美国学生…被领养 měiguó xuéshēng…bèi lǐngyǎng), they understood.

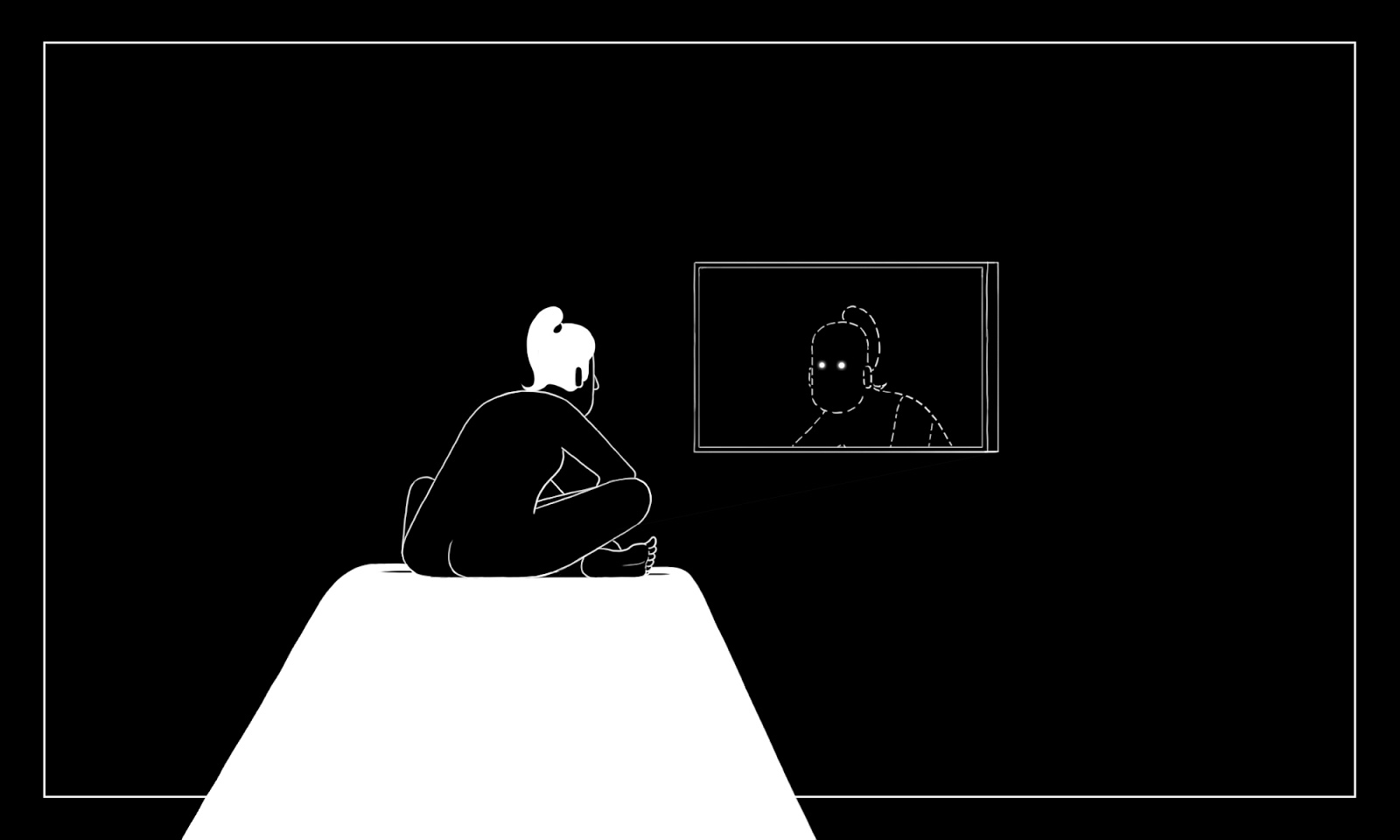

Spending time in China confirmed something I had always feared: I would never entirely fit in anywhere. I was constantly drifting between two worlds, alternating between a hypervisible and an invisible existence.

Although my experience abroad complicated my understanding of my sense of belonging in the spaces I occupied, it also motivated me to embrace this idea of living in between. In order to position myself more directly in the center of the divided space, I knew I needed to improve my language skills. I began formally studying Chinese during my first year in college. As I became more immersed in my language studies, I grew more intrigued by the complexities of existing with multiple linguistic and cultural identities.

I returned to China in the spring of 2019 for an intensive language immersion program in Beijing. By this time, I had been studying Chinese for five semesters, and although I was far from fluent, I had progressed beyond “Hello, I’m an American student.” I took a pledge to speak only Chinese for the entirety of the semester. I believed that this would be a great way to advance my language skills, but for some reason, the stakes felt even higher. It was almost as if sticking to the pledge would allow me to more closely experience what it was like to really be Chinese, to blend in beyond physical appearance. Breaking it would feel like admitting that I’d always be more American than Chinese.

Even though I was better able to express my thoughts and navigate daily situations, I began to realize that no matter how much I improved, I’d never really get much credit for the progress I was making. Whenever non-Chinese foreigners spoke even a single word in Chinese, they received instant praise, yet when I spoke, people just wondered why my Chinese sounded so bad. Judging me by my looks, people expected me to be fluent, which at times made me feel like there was no room for mistakes. For me, studying Chinese felt like being in a rigged race, one in which no matter how hard I ran, I could never get out in front.

As a transracial and transnational adoptee, I began my life with loss. Studying Chinese during college and living in China were parts of my process of learning to live with and make sense of this loss. Finding ways to share pieces of my own story is another part of this process; however, the perpetual silencing of adoptee voices in online spaces makes this difficult. When adoptees choose to share pieces of their own stories, they often receive backlash if they challenge the dominant adoption narrative. There is an unfair expectation that adoptees must be eternally grateful for a “second chance” at life. In truth, telling adoptees that they must be grateful or that they are “lucky” only dismisses the true complexities of adoptees’ experiences.

As a child, I only wanted to blend in; I was not interested in calling more attention to my differences. Over the past four years, during this time of exploration, I have started to embrace the parts of my identity that I used to completely disregard. I now feel compelled to find more ways to share pieces of my story and contribute to the existing efforts to amplify adoptee voices. Being a Chinese adoptee is certainly not the entirety of who I am, but it informs the perspective I bring to the work that I engage in. As I’ve come to realize the power of this perspective and how the world needs more people who exist in between, I no longer lie awake at night wishing to be white.

Resources by adoptees, for adoptees and anyone who is curious

Articles

A ‘lost’ daughter speaks, and all of China listens: A Chinese adoptee reflects on her experience of searching for her birth parents.

On being adoptee: A three-part series dedicated to illuminating the experiences of transracial adoptees.

Blogs

Red Thread Broken: A blog by a Chinese adoptee who has been sharing her thoughts online since 2013.

The Lost Daughters: An adoptee-centered space for adult women who were adopted as children to share their stories.

Film

Side by Side: An online video installation documenting the stories of over 100 South Korean adoptees.

Twinsters: The story of two South Korean adoptees, raised on different continents, who find each other on Facebook and believe they must be twins.

Podcast

A conversation with two Chinese adoptees in the U.S. on the Sinica Podcast.

They call us adoptees on They Call Us Bruce.

Organizations

Adoptees for Justice: An adoptee-led nonprofit that works to empower transnational and transracial adoptees.

China’s Children International: An international network created by and for Chinese adoptees. It has compiled a resource guide for adoptees, adoptive parents, and professionals who are interested in adoption. It includes some of the links attached above and many more.