China’s relationship with Southeast Asia, explained

Southeast Asia has become a “battleground” for U.S.-China competition — much to the dismay of the people there.

In 1296, the Chinese diplomat Zhōu Dáguān 周达观 arrived at Angkor, the seat of Cambodia’s ancient Khmer Empire, in one of the earliest recorded instances of Sino-Khmer diplomacy. There “is a gold tower flanked by twenty or so stone towers” and a “golden bridge flanked by two gold lions,” Zhou wrote of the Angkor temple complex. “I suppose all this explains why from the start there have been merchant seamen who speak glowingly about ‘rich, noble Cambodia.’”

But Zhou’s mission went beyond flattery. He had been sent by the Emperor Temür Khan to secure Cambodian tribute — essentially, payment demonstrating Khmer recognition of the Chinese emperor’s superiority. Ancient China extended this “tribute system” from Japan to Southeast Asia, thereby enhancing the ideological legitimacy of Chinese rule over tiānxià 天下 — “everything under heaven” — boosting the Chinese military’s credibility, and allowing the empire to benefit economically from such appeasement. While it is unknown if Zhou did, in fact, secure Cambodian tribute, China-Southeast Asia relations were for the better part of 2,000 years conducted under these Sino-centric auspices.

Due to these historical Chinese-Southeast Asian ties, the 30 million ethnic Chinese scattered throughout, and Southeast Asian geography — it links the Pacific and Indian Oceans — the region holds a special place in China’s policy mind. Since the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) came to power in 1949, Beijing has repeatedly involved itself in Southeast Asia; since Chinese President and CCP General Secretary Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 came to power in the early 2010s, China has re-upped its interest in the region, trying again to integrate Southeast Asia into some Sino-centric order, this time described as a “community of common destiny” (CCD). The CCD, like Beijing’s more global “community of shared future,” is intimately associated with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s global development program. A Sino-centric “community” is China’s goal; the BRI knits it together.

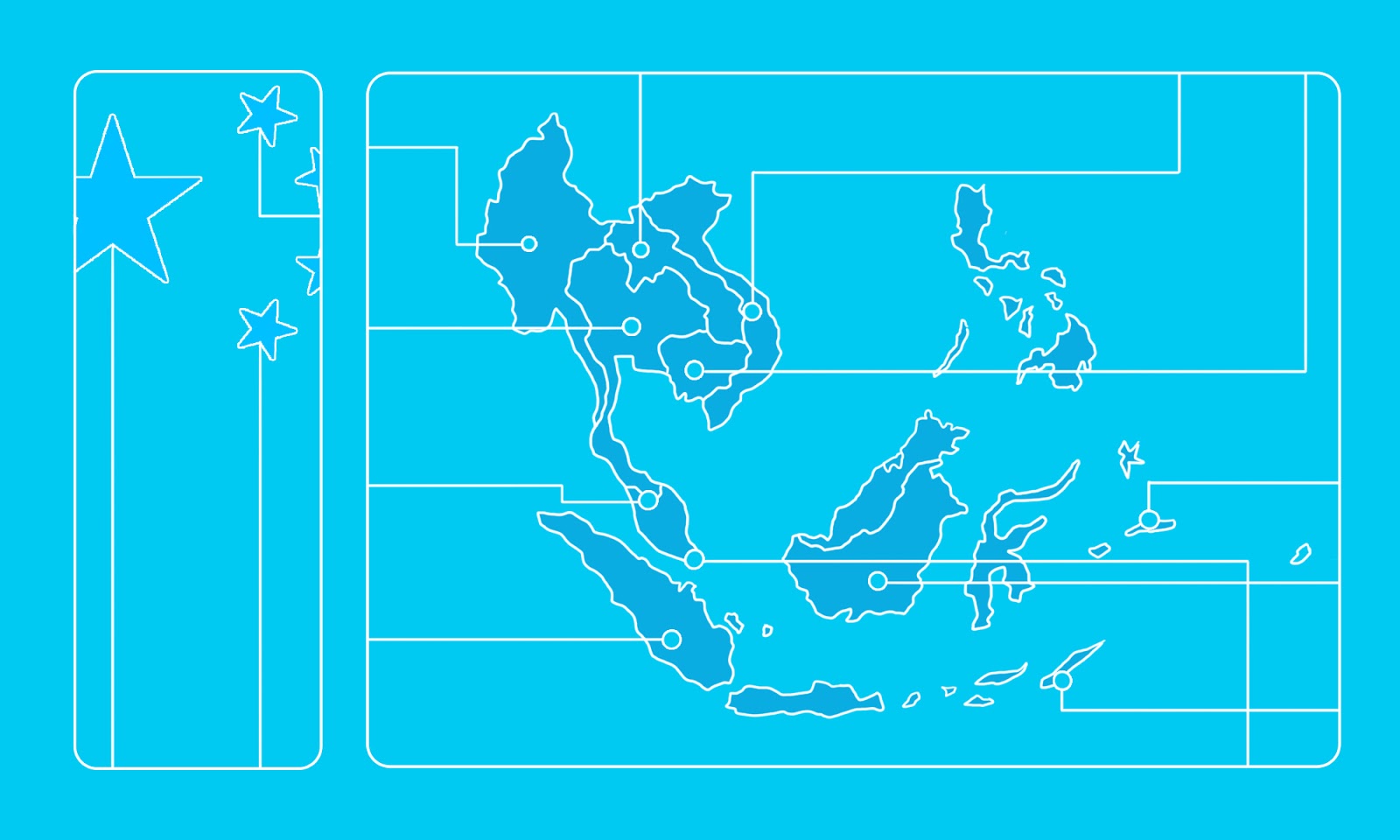

While every country in Southeast Asia is a BRI member, Xi’s CCD has found uneven purchase in Southeast Asia. Cambodia and Laos have attached themselves to China, but others, like Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore, have engaged with Beijing more carefully, trying to play the rising Chinese Great Power against its American rival to extract goods from both. Meanwhile, Vietnam — which China colonized for over a thousand years and invaded more than any other country in Southeast Asia — remains the most China-skeptical country in the region.

Yet Southeast Asians are unhappy that their region is now a “battleground” for U.S.-China competition, but China, much to American consternation, has indeed made substantial headway in folding many of its countries into a global order free from Western influence.

The vassals

In the early 1990s, China began repairing its broken (or at least hostile Cold War-era) relationships with Cambodia and Laos. The effort paid off: By the mid-2010s, both had embraced China more than any of their Southeast Asian neighbors did.

Their reasons for doing so are manifest. Both are authoritarian countries keen to graduate from Least Developed Country Status and have, accordingly, accepted vast economic aid and investment from China, largely through the BRI, which comes without the democratic and human rights strings attached to Western assistance. China is now the largest source of development assistance in both countries.

But with Chinese money comes Chinese control. A Chinese firm recently seized Laos’s electrical grid; China reportedly has secured access to multiple military facilities in Cambodia.

With Beijing’s cash comes also its politics. Both Cambodia and Laos are willing partners on this front, helping to block the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) from criticizing China’s militarization of the South China Sea and signing letters to the United Nations supporting China’s persecution of Uyghurs and crackdowns on Hong Kong, for starters. Other examples of appeasement abound, most obviously in Cambodia.

Laos and Cambodia may appear to be dancing similar steps, but they are not moving to the exact same tune: Laos has wisely diversified its investors in a way that Cambodia has not.

Still, for both countries, the question is no longer whether they will remain attached to China, but how they will manage the evident consequences of doing so, particularly as anti-Chinese sentiment spikes due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Laos’s leaders appear to at least be having the conversation about potential over-reliance on China; no such debate seems to be taking place in Cambodia.

A reluctant vassal?

A few years ago, Myanmar appeared to be breaking away from China. Indeed, the country in 2011 tried to free itself from China’s grasp by pulling out of a $3.6 billion dam project and beginning to implement reforms encouraged by the United States.

In 2020, however, the former pariah state is once again facing Western isolation for its military’s violent expulsion of some 700,000 Muslim Rohingya in 2017. Xi’s China has unsurprisingly sought to fill this vacuum. Xi visited Myanmar in January to discuss issues including the dam, inked dozens of BRI deals, and expressed support for the country’s government. Myanmar’s de facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, told reporters: “It goes without saying that a neighbouring country has no other choice but to stand together [with China] till the end of the world.”

Despite long-running tensions between the two countries, Myanmar is now again increasingly reliant on China, which has both economic and strategic interests in the country. Myanmar, meanwhile, has also supported China’s persecution of Uyghurs and crackdowns on Hong Kong.

And while Myanmar’s leaders and citizens may not be particularly interested in becoming vassals of Beijing, but reality — namely Western isolation of the still-impoverished nation — could force them to reconsider.

The accommodators

While remaining on reasonably good terms with the United States, Malaysia and Thailand make little effort to hide their preference for China.

Indeed, despite the former Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s 2018 warning against a new Chinese colonialism, he deepened ties with China, and by 2019 was telling international media that he would rather side with China than the “unpredictable” United States. Malaysia’s ongoing political turmoil is unlikely to disrupt Sino-Malay ties.

Thailand, for its part, is fairly full-throated in its support of China, despite being a U.S. treaty ally. Washington considers China a threat; Thailand does not. Since the 2014 military coup that brought the current regime to power, Thailand has deepened its military relationship with China. And while the protesting Thai masses hold anti-China, pro-Tibet, pro-Hong Kong, and pro-Taiwan views, they are unlikely to undermine Sino-Thai relations moving forward.

The balancers

Brunei, the Philippines, Singapore, Vietnam, Timor-Leste, and Indonesia balance the United States and China despite perhaps preferring one or the other — or, as Indonesia does, holding both at arm’s length. These countries maintain effective relations with both, arguing, as Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has repeatedly, that they should not be forced to choose between the United States and China. Rather, they intend to capitalize on China’s ascendance while maintaining strong ties with the U.S.

Brunei and the Philippines, another U.S. treaty ally, tilt somewhat toward supporting China, but both regime and public wariness of Beijing prevents them from aligning too closely with the Asian giant. This has not, however, stopped Manila from expressing its support for China’s Xinjiang and Hong Kong policies.

Singapore, meanwhile, is perhaps the best “hedger,” maintaining an extensive relationship with China while remaining a solid U.S. partner and global financial hub. Timor-Leste, for its part, maintains positive relations with the United States while remaining open to Chinese assistance: China constructed the young nation’s Parliament building and foreign ministry headquarters, also selling the country naval patrol boats and training dozens of government officials. Still, in 2019, the country’s former foreign minister declared, “The idea that Timor-Leste’s been tapped mainly to serve the interest of one single country, namely China, is completely wrong.”

Indonesia, on the other hand, does not seek a particularly close relationship with either Washington or Beijing. Instead, Jakarta considers Southeast Asia its natural sphere of influence and sees both China and the United States as infringing upon what is rightly Indonesian space. Indonesia is, accordingly, among the most aggressive when it comes to standing up to China.

Last is the curious case of Vietnam, which continues to cooperate with China despite widespread national distrust of China dating back thousands of years. Hanoi has delicately managed this relationship, leveraging domestic anti-Chinese sentiment when politically expedient while keeping open channels with Beijing and asserting Vietnamese sovereignty in the South China Sea and region more broadly.

Still, discord is inevitable. Months after the two countries’ defense ministers met in 2019, a former senior Vietnamese foreign ministry official accused China of “intimidation and coercion. In April, a Chinese maritime surveillance vessel sank a Vietnamese fishing boat in the sea. These incidents suggest that Vietnam-China relations are headed for rough waters, of which the United States will certainly hope to take advantage.

“Ground zero”

Despite Southeast Asians’ wishes to avoid being forced to choose between the United States and China, their region has become the “ground zero” of Great Power conflict between the two. Beijing, given its seemingly unending ability to marshal funds, is winning, but the competition is far from over, namely because the United States retains an overwhelming soft power advantage in Southeast Asia. Whereas a litany of complaints about China is driving widespread anti-Chinese sentiment, Southeast Asians retain a long-running preference for the United States.

Still, Beijing’s ambitions to reinstall some form of its ancient tribute system in Southeast Asia — to reassert in some modern form its claims to tianxia — are unmistakable. And while Southeast Asians are not ready to embrace China’s “community of common destiny,” an emboldened Beijing will not stop trying to bring them on board any time soon. More likely is the intensification of the Great Power conflict that Southeast Asians, knowing their history, desperately hope to avoid.