Some commentators called her a traitor but the crowd didn’t care, cheering her with all the frenzy due to a national hero: “Lang Ping, we love you!” During the Beijing Olympics of 2008, the U.S. women’s volleyball team was coached by a Chinese woman who towers over the world of Chinese sport (at 6-feet-2, this isn’t just a metaphor). It’s rare for an athlete to have a star-studded playing career followed by a star-studded coaching stint, but few people are like Láng Píng 郎平, China’s Michael Jordan, the most famous, celebrated, and accomplished Chinese athlete of her generation.

Her story is now being told in a major blockbuster, Leap, starring legendary Chinese actress Gǒng Lì 巩俐.

Lang Ping, nicknamed “The Iron Hammer” for her thunderous spikes, is a woman with the Midas touch — every team she touches turns to gold (or at least goes up in the rankings), rising from mediocrity to glory (in China’s case, three times).

It’s because of her that the “women’s volleyball team spirit” is harnessed by state media, inspiring Chinese leaders and (supposedly) even nurses working in COVID-striken Wuhan. It’s the idea that in order to win, the Chinese should work as a team and never give up, regardless of the odds.

It’s the main theme of Leap. But the movie is also centered on Lang Ping, its figurehead. For the Chinese, she’s much more than just a volleyball coach: she’s one of the earliest figures of China’s resurgence.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-5keDVTbowE

Who is Lang Ping?

Although she’s given few interviews on her childhood, likely it was tough. Born into a poor family in Tianjin in 1960, according to Sohu Sports she didn’t get very much to eat. She slept on a wooden plank and had only three sets of clothes. “Life was like that back then, nothing strange about it,” her mother, a hotel manager, said brusquely when questioned about it.

Life took a lucky turn due to a rejection in middle school. Although she enjoyed sports and wanted to go into basketball like her sister, the coach advised she try volleyball instead. At 13, she joined her school team.

Volleyball suited her. In a profile for the Fédération Internationale de Volleyball (FIVB), Lang Ping said that once she started playing and realized it was a team sport, only then did “it became of interest to me.” She became known for her formidable spikes, leaping up and smacking the ball down with ferocity. Her arm movements were stylish but powerful, her tactics varied to keep opponents off-balance.

It made her stand out. China opened to the world of international sports in 1976, but decades of isolation under Mao meant the country had a lot of catching up to do before it could win anything.

In 1978, at just 18, Lang joined China’s first women’s national volleyball team as an outside hitter: the main attack position. The team exploded onto the world stage, winning the FIVB 1981 Women’s World Cup and the World Championships of 1982 (with Lang named tournament MVP).

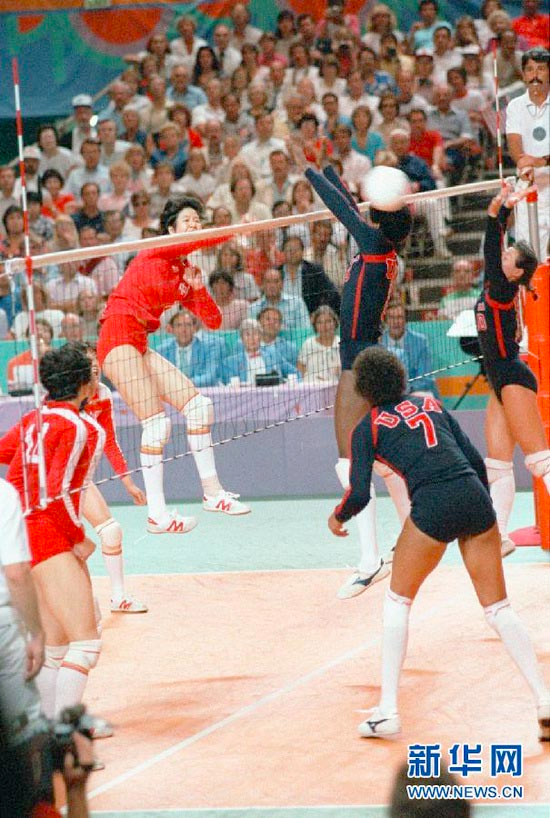

Lang became captain in time for the glory of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. Years of Chinese sporting underachievement came to an end when the team won gold, trumping the home U.S. team 3-0 (Lang Ping winning MVP of the entire tournament). Although it’s left out of the Chinese narrative, Lang has spoken about the pressure the team was under. They were micromanaged and remained in their hotel rooms, given strict instructions to only say positive things. “We were trained like that to talk the same, act in a certain way,” she told The New York Times. “Our mind was less open then.”

The gold medal came when China desperately needed a confidence boost, a successful Olympic team proof of a successful nation. Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 has said he remembers that time as one of national euphoria. It wasn’t just about volleyball — it showed that as a nation, China was getting back in the game.

It was the birth of the “women’s volleyball team spirit.” As reported by the South China Morning Post, future government leaders led campus rallies promoting imitation of the team’s spirit. State media and government departments saw it as an essential mindset during China’s rapid economic rise.

Although her teammates filtered into officialdom, Lang Ping stayed on as an assistant coach. This was more of a challenge. “As a player all you have to think about is producing your best performance on the court,” she later told FIVB. “But as a coach you have to consider the players, training, competition and even elements off the court that may help or harm the team.”

But the attention was getting too much for her. Her wedding was recorded on national TV (she was very “embarrassed” by that) and her face put on stamps. “People often recognized me and made me feel like not myself,” she wrote in an autobiography in 1999. Her height would immediately give her away, so disguise was of little use, and she spent more and more time at home. “I felt restricted even when I went shopping.”

She may also have wanted to buck the Chinese stereotype that athletes have no education because they spend all their time training. She studied English at Beijing Normal University after she retired as a player in 1986. In 1987 she moved to Los Angeles and coached the women’s volleyball team at the University of New Mexico. There were things to get used to: unlike the Chinese team who believed it bolstered team spirit, Americans didn’t live and sleep together in dorms.

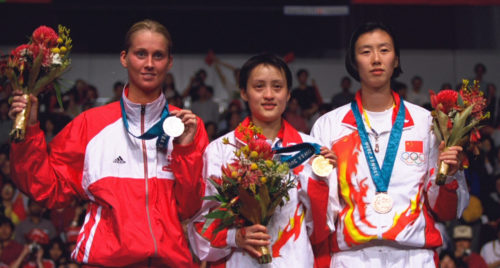

Chinese women’s volleyball suffered without her. By 1995, China was 8th in the World Championship rankings. A team so closely tied to national morale couldn’t be allowed to fail. Lang was asked to return as head coach, which led to a silver medal at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta (perhaps why she was FIVB Coach of the Year for 1996) and second place in the 1998 World Championships.

But Lang resigned from the national team that year, citing health reasons (although an unconfirmed rumor said there was a power struggle between herself and China’s sports regulator). In 1999 she became head coach for an Italian volleyball league team, accompanied by her usual shower of honors and success.

Then the U.S. came asking for help — in 2005, after their third consecutive Olympics with no medals. American players seemed quite thrown off by the messianic level of their coach’s fame when playing the 2005 Grand Prix in China — parents throwing their children at her or trying to touch her shirt. To them, she was just “Jenny.”

This eventually led to an awkward 3-2 victory for the U.S. team at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, in front of Lang’s old team, 250 million Chinese TV viewers, and President Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛. Lang told the U.S. players not to get excited or pressured, just to focus on each point. Veteran Chinese player Liu Yanan noted a marked change in the U.S. team’s performance. They seemed to have become more fiery under Lang’s leadership, scorching on to win the silver medal, and jumped up five places on the FIVB world rankings.

It was a risk. Back in 2005, the China Olympic Committee’s website had warned that Lang’s importance to the Chinese team’s spirit meant “if [Lang] stands with the opponents during women’s volleyball matches at the Beijing Olympics, you can rest assured that this will be difficult to accept for the new Chinese players…and difficult for all Chinese watching.” But Lang thought differently. “I waited to see what was happening in China” before accepting the job, she told China Daily. “If there were too many people against this decision I probably wouldn’t have accepted the job. I didn’t want to give myself too much trouble.”

Although there was talk of her being a “traitor” — her choice to go with the Americans denied China a shot at gold — others saw a U.S. win as a Chinese victory anyway. If the Yanks wanted her as their coach, that was proof that China could produce quality. Even the Global Times, notorious for its nationalism, urged readers not to see Lang’s decision as a betrayal.

The Olympics in Rio 2016 was the climax. Lang had returned to China in 2013, coaching a local club in Guangdong for the stratospheric salary of 5 million yuan ($745,000) a year. But the owner believed it was in “the national interest” to hand her over to the national team, after China didn’t even reach the quarterfinals at the 2012 London Olympics. He even offered to keep paying her while she wasn’t coaching his team. She rejoined the Chinese team with a precise set of goals: first, to make China the leading Asian team in the world rankings. Second, to get a medal at the next Olympics.

From these simple goals came results Lang hadn’t even dreamed of. Not only did they win the World Cup in 2015, but also bagged gold at Rio, blazing unbeaten through every one of their 11 matches. It’s often trumpeted in China that this makes Lang the first in volleyball history to win an Olympic gold both as a player and a coach.

The turnaround was so spectacular that wisecracks said she should coach the Chinese men’s football team next (only Lang Ping could save a team that’s become a national laughing stock).

This story of rise and fall and rise makes it perfect movie material. The director of Leap was so keen to recreate the epic Rio matches as accurately as possible (perhaps with an eye on the historical record) that the real team played themselves, recreating their moves down to the smallest spin of the ball before a serve.

How to win games and influence players

What’s her secret? The usual ingredients — a passion for the game and giving it 100% — are only part of it. She drills her teams very hard, but always manages to inspire affection in them. “I love her,” said one Italian player in 2005. “She’s killing us, to be honest with you, but it’s what we need.”

Aggressive tactics in players need to be balanced with a cool, calculating head — in 2008 she said she often felt like a “cheerleader,” raising one quality and lowering the other as need be.

Victory has to be a “team effort” that also goes beyond the court — it’s about passing on experiences and knowledge to the next generation.

Laurels are never to be rested on, and the victory’s in the detail. If you constantly play like every point counts (even when winning), the big picture will take care of itself.

This perseverance seems to have impressed Xi Jinping, who noted that even when victory was assured at the World Championship in Japan in 2019, “You didn’t slack off during the last game and went for every ball.” For him, the team is a national treasure not just for its many victories, “but also because you have displayed the spirit of putting the motherland first, through unity, cooperation, tenacity and never giving up…[it] embodies the strongest will of the Chinese nation to rejuvenate itself.”

The Tokyo Olympics were meant to be the next big demonstration. Lang and her team can be found gracing billboards across China, in preparation for the now-delayed event. As was the release of Leap — delayed during the Spring Festival owing to COVID, opened during this past National Day holiday. It took in more than 100 million yuan ($15 million) on its first day alone, reminding audiences what can be achieved when groups work hard and work together. But only giving 100% is acceptable: “Volleyball is not only our work, but also our whole lives,” Gong Li, playing Lang Ping, says in the film.

Not quite, of course: Lang has announced she will retire after the Tokyo Olympics to spend more time with her family. When encouraged by a CGTN interviewer to repent by turning volleyball into her life, Lang replied, “I don’t think so. It’s going to be a very hard decision to continue.”

But Lang Ping’s example will no doubt be a guiding light for years to come. “No matter what challenges you face, do your best,” she has said. “Believe in the power of hard work and victory will surely belong to those who never give up.”

It’s a mindset that made Lang a national hero — and China the current No. 1 in the world rankings for Women’s volleyball.

Chinese Lives is a weekly series.