How Maoism shaped many of China’s leading entrepreneurs

Chairman Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 died more than 40 years ago, yet his ideological principles live on in the Chinese population. Research has shown that many Chinese entrepreneurs may exhibit a lasting Maoist “imprint” that enduringly shapes their thought and actions.

“Huawei’s culture is the culture of the Communist Party of China (CPC), and to serve the people wholeheartedly means to be customer-centric and responsible to the society.”

*Note: Links in this article are mostly to Chinese-language sources.

*****

Entrepreneurs are at the center of the private economy in China. Many of them are Communist Party members as well; in other words, they are communist entrepreneurs, or perhaps more accurately, Maoist entrepreneurs. They naturally combine an ideology based on Mao’s interpretation of communism with capitalist practice. Knowledge of Maoism is thus crucial to understand how business works in China, and how many of its leading entrepreneurs think.

One notable example is Rén Zhèngfēi 任正非, founder and CEO of Huawei Technologies Co, a Shenzhen-based company that has been caught in the crossfire of the U.S.-China tensions. The 75-year-old founder is a dedicated communist and has ingrained Party values in Huawei, a private company that is neither owned nor directly controlled by the Chinese government. As he says, “Maoism is the guiding principle (and soul) of Huawei…and management philosophy and strategy are commercial applications of Maoism.” Ren joined the army in 1969 and the CPC in 1978. He established Huawei in 1987 with an initial capital of $5,680 (¥21,000). By 2019, the company had earned $122 billion in revenue, according to the company’s year-end report.

Ren’s Huawei, collectively owned by its employees, rotates co-CEOs, which reflects Mao’s personnel strategy of swapping positions among different military leaders so that all of them have a broad scan of different situations. This has the added benefit of ensuring that none of the co-CEOs can entrench their power and potentially threaten Ren.

The company also adopted Mao’s “sieging the city from villages” strategy: The CPC started the revolution in villages to gain support from farmers, and then based on that strength, it mobilized workers in factories in cities. Ren realized that as Huawei faced tough competition from foreign rivals in its early years, “only in villages did Huawei have a chance,” so he sent his salesforce to rural areas to sell Huawei’s network switches and build its market village by village. Starting from lower-income markets away from urban centers, Huawei gradually moved to big cities, the entire country, and eventually the world.

Maoism and the private economy in China

Maoism is an adaptation and extension of Marxism-Leninism to the agricultural, pre-industrial Chinese society in order to conduct a revolution in China and pursue economic construction. This ideology is reflected in a collection of Mao’s works, quotes, and other speeches. On the one hand, Maoism has a foundation of orthodox communist principles. Like traditional communism, Maoism maintains a one-party monopoly of power, state control of the media, and state ownership of the means of the production and firms. It emphasizes government regulations and plans. Capitalism, on the other hand, usually has a multiple-party system, free press, mostly private ownership, and less comprehensive government plans and regulations.

But Maoism also diverges from orthodox communist ideology in a number of important ways. For example, the idea of “sieging the city from villages” noted above differs from Marx’s and Lenin’s idea that the revolution should start among the working class in cities. Specifically, Mao’s novel ideological principles mainly include (1) “seeking truth from facts,” (2) nationalism, and (3) adhering to the “mass line,” which suggests a focus on devotion to society. Admittedly, there are many other Maoist elements that deviate from orthodox Marxism-Leninism, such as frugality, but in this essay, we mainly focus on nationalism and the devotion to society. Nationalism is reflected in Mao’s emphasis on autonomy, independence, and self-reliance, and a hesitation to see communism as a global project. Devotion corresponds to the mass line concept that the CPC should connect tightly with the popular masses and serve the people.

For more than four decades, most accounts have attributed the unique form of capitalism developed in China to its former leader Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平’s formulation of a “socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics,” which laid the conceptual groundwork for the country’s transition following Mao’s death. Many writers have suggested that the framework downplays communist political ideology and emphasizes a capitalist market ideology, which over time will become increasingly important. Visitors to China who see the world’s biggest 5G network, skyscrapers, electric cars, and advertisements everywhere for luxury goods may find it difficult to believe that there is anything communist left in China. However, despite China’s growing middle-class population and vibrant markets, there has been no real political change or democratization. In many ways, the system has become more Maoist in recent years.

Many of the people leading both government and industry in China grew up immersed in Maosist ideas. Many entrepreneurs are Party members who went through a rigorous indoctrination process, including attending the Party meetings, learning the Party constitution and principles, and pledging loyalty to the Party and its ideology.

Ren is a good example of the enduring effects of early experiences in the CPC and in particular the lasting effect of Maoism on his thinking. When Ren joined the CPC, he went through the indoctrination and socialization process that included swearing that he would “be loyal to the CPC, fight for communism his whole life, sacrifice himself for the interest of the people and the CPC, and never betray the Party.” On different occasions, Ren has suggested that he still kept this word. If the interests of the CPC conflict with those of Huawei, he would “choose the CPC whose interest is to serve the people and all human beings, and he could not betray the principle of serving all human beings.” Ironically, given the recent suspension of Alibaba Group’s Ant Financial IPO, Jack Ma (马云 Mǎ Yún) — the founder of Alibaba Group and a CPC member — has similarly publicly said that the company is ready to surrender this business to the Chinese government and Communist Party.

Maoist entrepreneurs and internationalization

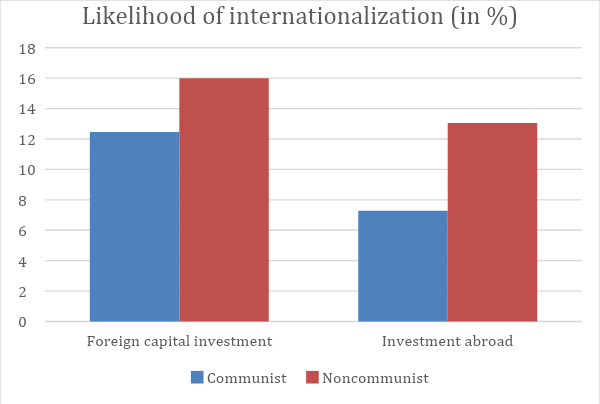

Chinese communist entrepreneurs exhibit distinct behavioral patterns, corresponding to Mao’s ideological principles. Mao’s teaching promoted a strong sense of nationalism and portrayed foreign capitalists as exploitative, mercenary, and ruthless. Our research shows that those who went through communist ideological training were more likely to be antagonistic to foreign capitalists: Communist entrepreneurs are 22.1% less likely to accept foreign capital investment in their firms and 44.1% less likely to invest abroad. These two effects, as the graphs below show, are substantial.

Autonomy, independence, and self-reliance are at the core of Mao’s vision of nationalism. For example, Yǐn Míngshàn 尹明善, the founder of the Chinese motorcycle and automobile company Lifan Group, whose firm has recently faced financial difficulties, urged Chinese entrepreneurs to be wary of globalization. “Foreigners are unreliable and we have to rely on our own,” said Mao in 1945, a principle Yin followed. According to Yin, Chinese entrepreneurs did not benefit from globalization, since they had to pay huge premiums for natural resources and technologies controlled by other countries.

The ideals of independence and autonomy are also deeply rooted in Huawei’s culture. Ren constantly pushes for autonomous innovation and has institutionalized a mandate that at least 10% of sales revenue should go to R&D. He said, “Foreign firms are only after money in China. They would not teach Chinese technology and are not reliable, and we would never become independent by buying their technology directly.” Now Huawei is among the most innovative firms in the world, with the fifth-largest R&D expense ($12.5 billion) and ranked seventh in patent holding worldwide.

Communist entrepreneurs and philanthropy

Many communist entrepreneurs also aim to follow the Maoist principle of sacrifice and devotion to the people, at least in some of their public words and actions. A typical way to show their focus on devotion to the people is distributing their profits for philanthropy, helping the poor, and other government-proposed projects. For example, Hǎijiāng Zhōu 周海江 — the chairman and CEO of the $7 billion annual revenue conglomerate Hongdou Group — actively participated in the “Grace Project,” a poverty-alleviating governmental program. More recently, communist entrepreneurs also actively responded to the Party’s call to fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, Yǒngxiáng Wèi 魏永祥 — the founder, chairman, and CPC secretary of Henan Tiejun Culture Media Co. Ltd — mobilized CPC members in his firm and volunteered to help the epicenter of Wuhan. Before the team departed, Wei wrote that “this is the responsibility of CPC members, and when the CPC government is in need, we CPC members should stand in the forefront and be ready to sacrifice for the CPC.”

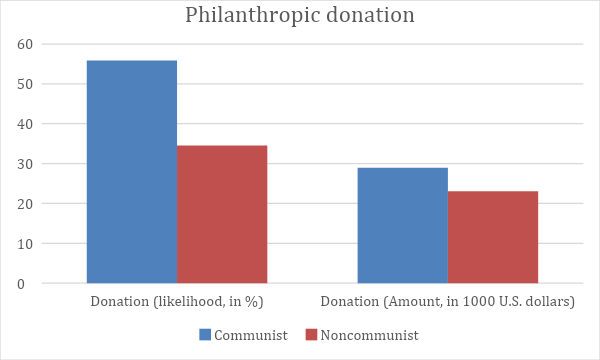

As a result, as our research suggests, communist and noncommunist entrepreneurs differ greatly in their philanthropic interests. Communist entrepreneurs are 61.8% more likely to donate than their noncommunist counterparts (the likelihoods of donation by communist and noncommunist entrepreneurs are 55.84% and 34.52% respectively). Their amount of donation is $6,000 more (23% of the average $26,000). A recent finance study provides similar evidence.

Learning from the government

However, these deep differences do not mean that the communist entrepreneurs are unchangeable. For example, an important aspect of Mao’s teaching is that CPC members must respond to the Party’s call. Following the “reform and opening up” post 1978, the Party has increasingly supported foreign investment and exposure. As a result, some communist entrepreneurs became more likely to adjust to the globalization period. Our research shows that communist entrepreneurs are more likely to cooperate with foreign business partners after receiving guidance from the CPC government, such as through serving in the People’s Congress. For example, Chén Jiànchéng 陈建成 is a communist entrepreneur and the founder and CEO of Wolong Holding Group Co., Ltd — a large business conglomerate that controls three publicly traded firms and has $1 billion in total assets. As a delegate to a provincial-level People’s Congress, he was encouraged by the CPC government to go global. Wolong Holding Group correspondingly organized personnel training programs for its internationalization strategy and has invested in more than 20 countries around the world. The company is now one of the most successfully globalized firms in China.

*****

Seeing Chinese entrepreneurship through our Maoist lens, it is not hard to understand why despite the growing population of the middle class and entrepreneurs, China is still tightly controlled by the CPC. And even many young Chinese who did not experience the Maoist period at all are reinventing Maoism when their country is increasingly globalized and marketized. About 70% of users in a recent survey on Zhihu, a social media platform similar to Quora and Reddit, thought Mao was the greatest Chinese person of all time. In conclusion, our main thesis can be summarized with a variant of Karl Marx’s famous assertion in the Communist Manifesto: “A specter is haunting China, notably in the private business sector, the specter of Maoism.”