Wall Street blunts the ‘delisting’ hype

The retreat of Chinese companies from American capital markets is an overblown story, argues Kevin Xu. On the contrary, the last year has seen the most Chinese fundraising in the U.S. since 2014.

The “delisting” narrative of Chinese companies from the U.S. has largely not materialized. Instead, just about every other week, there’s news of a new Chinese company about to IPO in New York. The next one, Lufax, may even end up being the largest fintech IPO in U.S. history, with its high-end fundraising target at $2.36 billion.

So far in 2020, U.S. IPOs by Chinese companies (“Chinese” here is defined as the company’s corporate headquarters being located in China as stated in its S1 or F1 filing) have raised $9.1 billion — the most since 2014. Of course, 2014 was an anomaly with Alibaba’s IPO raising a then-record $21.8 billion.

With all this geopolitical tension and some concrete legislative action in the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act (HFCAA), why are Chinese companies IPOing in the U.S. undeterred?

I believe Wall Street’s IPO business model has something to do with it.

The first-day pop

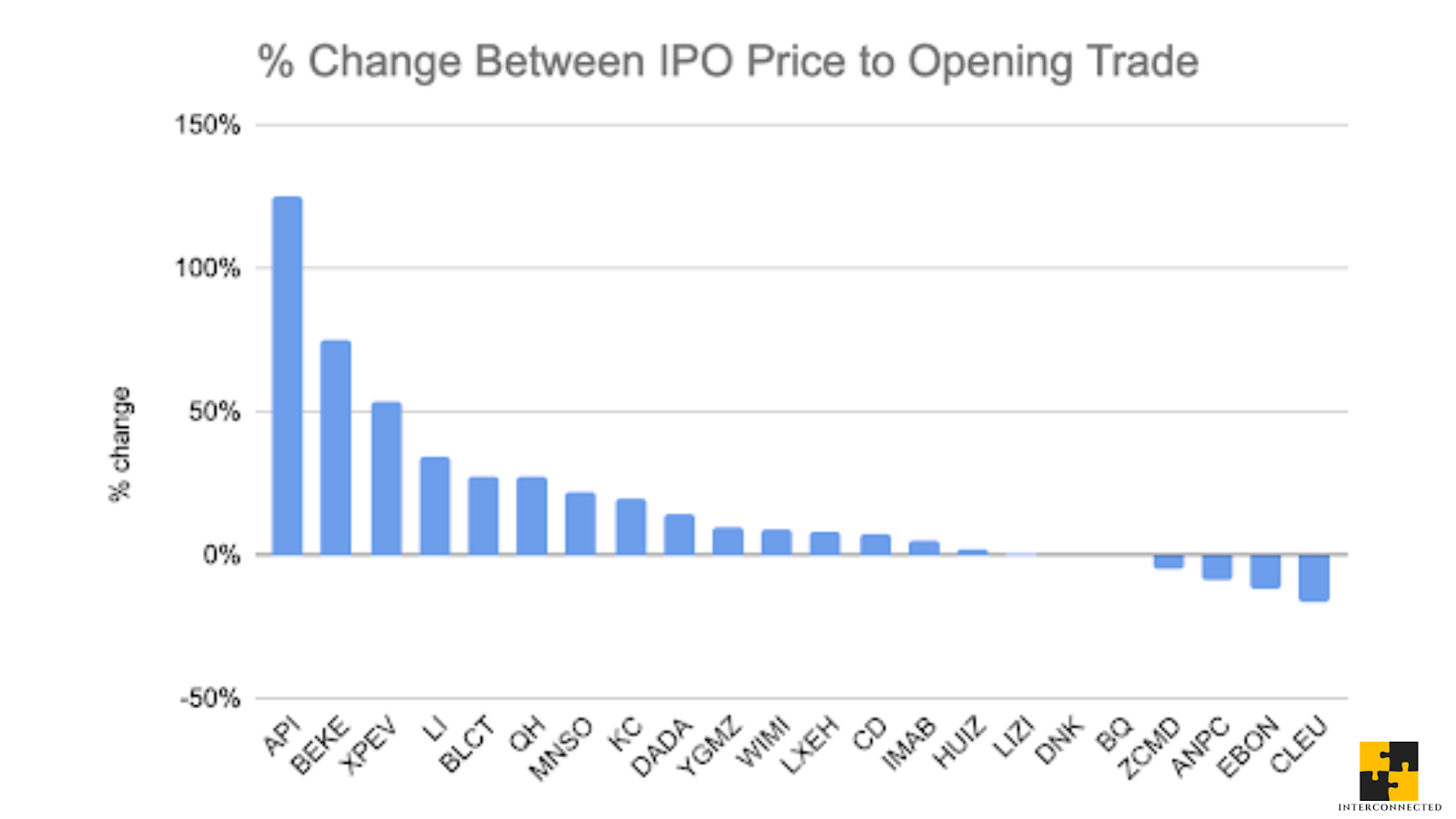

Before diving into the IPO business model (and its recent competitors), I first want to show you this chart I plotted. It shows all the U.S. IPOs by Chinese companies thus far this year (not including Lufax), and the percentage change of each company’s IPO price, and its opening day’s first trade price. Many of these are fast-growing but unprofitable tech companies.

As you can see, some companies had the proverbial “first-day pop,” like video and interactive broadcasting software maker Agora (API) and real estate industry software provider KE Holdings (BEKE), while others’ shares started falling immediately after trading began. The median “first-day pop” is 9% and the mean is 18%. Most of the companies that enjoyed a decent “pop” also raised much larger rounds than the ones that didn’t — electric car company XPeng (XPEV) raised more than $1 billion and BEKE raised more than $2 billion.

The IPO model: You need size, volume, and relationships

I plotted this chart because it illustrates a key part of the IPO business model for the Wall Street bankers who facilitate them. Explained simply, an IPO is a size + volume-driven and relationship-driven business.

The size + volume part is straightforward — bankers typically take a 7% commission based on the size of the IPO or amount raised, so the more money an IPO raises the better. Only in rare cases where the IPO company is super hot, like Facebook, does that commission decrease. And the more IPO deals that happen, a.k.a. volume, the more money bankers get to make.

The relationship part is connected to the “first-day pop.” Because the bankers sort of represent both sides of the table — helping the soon-to-be-public company sell shares at a good price and helping the investors looking to buy shares of new public companies at a good price — their job is to make both sides “happy.” Bankers can make sure the company is happy by engineering a “first-day pop” that produces positive headlines and a big internal morale boost, while still raising the amount of money the company wants. And bankers can make sure their investors (also clients) are happy by manually allocating these IPO shares to them — shares that are not available to others — so when the “first-day pop” occurs, these investors can sell it for a quick, handsome profit should they choose to.

In addition, there’s also the so-called “greenshoe option,” where the underwriting bankers get an additional 15% of IPO shares to sell within 30 days after the IPO day. Being able to deliver this “access” to clients makes the bankers look good and solidifies client relationships with rich investors, who would want to work with the same bankers for the next IPO. It’s a repeat-player business.

I’m glossing over many intricacies of the IPO process, but simply put, bankers want to deliver the biggest IPO possible with a “first-day pop” and do as many of these transactions as possible. Doesn’t work every time, but they sure do try.

Off-limits: Direct listing, SPAC

While it’s generally been a good IPO year, what makes Chinese companies especially attractive customers for New York bankers is that the alternatives to a traditional IPO — direct listing and SPAC (special purpose acquisition company) — are not viable options for Chinese companies.

Even from my simple description of the IPO business model above, it’s not hard to see that the process is problematic, specifically in its “dual-agency” setup where the bankers are representing the interests of both sides of the table. Influential venture capitalists, like Bill Gurley, have been criticizing this issue for many years. Thus, both direct listing and SPAC have been gaining prominence in the last two years as alternatives. SPAC’s popularity in particular has spiked this year.

To contrast these two alternatives with a traditional IPO in the plainest way possible: A direct listing lets a company’s shares trade publicly without raising any money (not yet allowed to), thus only providing liquidity and price discovery, while a SPAC raises money first, then uses that money to reverse-merge with a private company, thus taking that company public.

This blog post by the VC firm a16z has an eloquent comparison of the three options:

If you need money, an IPO, for all its flaws, makes the most sense and is probably the best option; if you don’t, a Direct Listing may be preferable; if you need money, speed, and certainty, a SPAC may be best.

The ongoing discussions about the pros and cons of these two new options vis-a-vis an IPO inside both Wall Street and Silicon Valley are fascinating and fierce. But they are both off-limits to Chinese companies seeking to go public in the U.S. because:

- Direct listing is for companies that don’t need new capital. To trade well, the company should have some public name recognition — Spotify was the first direct listing back in 2018. Few Chinese companies, especially fast-growing tech companies, are profitable enough to not need new capital, nor do they have big name recognition.

- The SPAC hype is mostly an American phenomenon, and there are plenty of private companies in the U.S. to target. It will be a long time, if ever, before American SPACs look for foreign companies to take public.

There are other “going public” options, just not good ones. With its rule change in 2018, the Hong Kong Stock Exchange now allows unprofitable companies to list, as does the new Nasdaq-like Shanghai STAR market. Both are trying to compete with Wall Street for business. However, the price and valuation for unprofitable companies tend to be lower, while both the higher valuation and reputational capital garnered from “going public in America” cannot be replicated. SPAC-like mergers are also available in Hong Kong, but they are usually relegated to poor-quality companies with no other options, which was the longtime reputation of SPACs in America as well until last year.

Essentially, unprofitable but promising Chinese companies need Wall Street. And Wall Street needs their business, too!

Unserious regulators

With Ant Group’s snub of the New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq to opt for a (now suspended) simultaneous dual listing in Hong Kong and Shanghai, Wall Street will be fighting extra hard for IPO business from China.

But what about all the pending legislation and harsh rhetoric against Chinese companies from the U.S. government? Just like the whole ByteDance ordeal — which now seems to be in suspended animation — I suspect the noise from the U.S. Congress and the president are more for show than serious efforts to regulate a legitimate inconsistency in our capital market. One example of the unseriousness of U.S. regulators is the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act (HFCAA), which stipulates that public Chinese companies that do not adhere to U.S. accounting rules or disclose Chinese government or CCP ownership or control could be delisting from U.S. stock exchanges.

When the HFCAA first passed the U.S. Senate back in May (and by unanimous consent, meaning every senator agreed with it, so they didn’t bother calling a floor vote to record who said “yes” and who said “no”), there appeared to be a lot of momentum behind the bill to gain approval in the House of Representatives, then to Trump for his signature. I had thought then that, given how unanimously anti-China Washington has been, legislators would fast-track the bill and claim a rare victory over China.

That didn’t happen. The last public statement made by anyone on this bill was in August by Senator Rubio, who introduced a similar bill called the EQUITABLE Act in 2019. (EQUITABLE stands for “Ensuring Quality Information and Transparency for Abroad-Based Listings on our Exchanges.” Yes, the congressional acronym game remains strong.)

To be clear, I’m generally in support of the core substance of the HFCAA. As I wrote in “Why Huawei should IPO in America” back in May, it makes sense for the SEC’s Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), the auditor of auditors, to enforce the same standards on Chinese companies as it does to all foreign companies listed in the U.S. Rules are rules, and they should be applied evenly across the board. I also don’t think such a change would force all Chinese companies to delist. There are ethical, ambitious entrepreneurs from China (and everywhere) who would welcome that scrutiny because their mission is to build a global, world-changing business and they crave the trustworthiness that comes with a higher regulatory standard. And the ones who do have problematic financial practices and shady connections will delist. It’s a self-selecting process.

Wall Street will lobby to deter or water down the HFCAA. Given the American financial industry’s mutually beneficial relationship with Chinese companies, that is to be expected. And as long as U.S. regulators lack the focus to put their feet down and do their jobs, Chinese companies of all shades of ethical standards will continue to list in New York, and bankers will happily continue to make money off them.

A version of this article originally appeared on Interconnected and is republished with permission. If you like what you’ve read, please subscribe to the Interconnected email newsletter.