Ant Group underfoot — why U.S. markets aren’t dead yet

The government may have just been waiting for the right moment to crack down on China’s internet giants, but why now? Why Alibaba? What happened behind closed doors?

On November 3, the Shanghai Stock Exchange suspended what was supposed to have been the largest IPO in world history. Investors had already signed up to buy $37 billion of shares in Ant Group, the fintech spin-off of China’s ecommerce giant Alibaba, whose own IPO just six years ago was the world’s largest at that time. Not only would Ant have broken its parent company’s own IPO record, but also it would have been the first time that the world’s biggest public offering took place on Chinese markets (in Shanghai and Hong Kong) rather than on Wall Street.

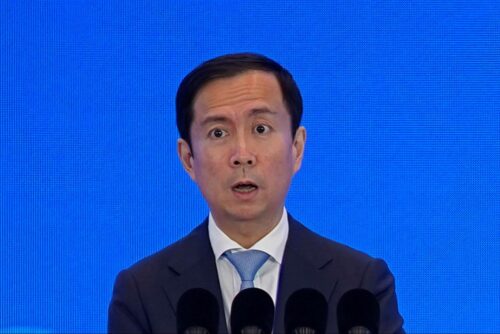

Jack Ma (马云 Mǎ Yún), the Alibaba founder who controls Ant, boasted in Shanghai on October 24 that this was “the first time that such a big IPO was priced outside of New York City, which we wouldn’t have dared to think about five, or even three years ago.”

But the Shanghai Stock Exchange postponed the offering with a letter addressed to Ant Group that said the “company’s actual controller [Jack Ma], chairman, and general manager were jointly subject to supervisory interviews by the relevant departments,” and that the “company also reported changes in the fintech regulatory environment and other major issues,” which may cause Ant Group to fail to meet requirements for listing.

The action against Ant seems to have speeded up a broader campaign by the Chinese government to rein in the country’s internet giants: On Tuesday this week, China’s antitrust regulator, the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR), issued draft rules (in Chinese) to stop anti-competitive practices in the internet sector. This has “negative implications for major internet companies with dominant positions across segments,” said Morgan Stanley analysts cited by CNBC, although the sprawling digital empire of Tencent with its WeChat world is an obvious target.

Ant underfoot

The government may have just been waiting for the right moment to crack down on China’s internet giants, but why now? Why Alibaba? What happened behind closed doors?

There was all kinds of speculation on the Chinese internet and amongst investors in China and abroad about rivalries, negotiations, and dirty deeds done behind closed doors at and to Ant Group and at various government departments. There is also the fact that Chinese fintech companies, and especially Alibaba, have pushed boundaries and taken risks, usurping business that had traditionally been the exclusive domain of state-owned financial institutions under tight regulatory supervision. Together with Tencent (a competitor), Ant has basically destroyed cash as an instrument for settlement in China. And perhaps most offensive to China’s regulators, Ant has become a gargantuan financial player without submitting to the rules that conventional banks and established financial institutions must conform to.

Chinese internet users themselves seem to think that Ant Group deserves its comeuppance. On social media platform Weibo, comments on the IPO suspension were overwhelmingly positive, based on a widespread feeling that Ant Group — despite filling an important niche by providing financial services to small businesses and individual borrowers — is actually a loan shark in disguise.

But whatever Ant’s sins, they have been going on for a long time. Ant Group was first launched by Alibaba in 2004 as Alipay, and many of its biggest new financial products are not that new: Yú’ébǎo 余额宝, its internet-only money market fund, launched in 2013. So why did the regulators slam Ant Group just days before the scheduled IPO? We’ll probably never know, but we do know this:

At the same financial forum where Jack Ma talked up the upcoming IPO, he said that traditional Chinese banks operated with a “pawn shop mentality” and complained about China’s financial regulators. Ma’s rant may have been the trigger for an unceremonious invitation on November 2 to be dressed down by China’s financial regulators, the “supervisory interviews by the relevant departments” mentioned above. But apparently, the interviews were not supervisory enough — the Ant executives failed to placate the regulators at their late-night meeting, or more importantly, the man who calls all the shots in China: Xí Jìnpíng 习近平.

If the Wall Street Journal’s reporting is accurate, it was indeed Xi’s displeasure at Ma’s speech that resulted in the IPO suspension. He “personally made the decision to halt the initial public offering of Ant Group,” reported Jing Yang and Lingling Wei: “Mr. Xi, who read government reports about the speech, and other senior leaders were furious, according to the officials familiar with the decision-making.” Further evidence: The Chinese service of Radio France Internationale reported “analyst” comments that Ma’s speech was like a “slap in the face to Wáng Qíshān 王岐山, the vice president of the country, which in turn was seen as challenging Xi Jinping’s authority.”

A massive IPO after eating humble pie?

Perhaps the humbling of Ant Group was inevitable, given the gargantuan size of the planned IPO and the power that would have been bestowed on Ma and his colleagues: The Chinese Communist Party is not comfortable having even a hint of competition for control over society.

The listing will probably go ahead at some point in the future, once Jack Ma and Ant Group have made the correct confessions and apologies, and made the correct adjustments to their business model to placate the “relevant departments.” One result will certainly be that state-backed financial institutions like the big banks and card network UnionPay get a bigger slice of the pie.

If the listing does happen, it might very well still be the biggest IPO the world has seen to date.

Thanks in part to Shanghai’s Nasdaq-like STAR market, China is experiencing a boom in share sales, which has helped to mint 257 billionaires over the past year. For entrepreneurs and investors turning to China’s capital markets, it’s as much a matter of repulsion as it is attraction: They are also being pushed there by the erratic and reckless actions of the Trump administration.

On October 14, the U.S. State Department proposed adding China’s Ant Group to its “entity list” of foreign companies that are considered a national security threat, according to a Reuters report. The move would place restrictions on Ant Group’s ability to buy certain American technologies and do business in the United States.

This proposal is based on emotion, not reason: Ant Group has almost no business in the U.S., and unlike Huawei, does not rely on American technology to operate in China. Adding Ant Group to the entity list is a noisy, furious talking point for Trump and U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, but it would accomplish nothing.

The Ant Group proposal was only one of the most recent moves against Chinese tech companies after nearly two years of blustery threats — as well as real bans and restrictions — that began in earnest in January 2018 when FBI Director Chris Wray said that telecom companies Huawei and ZTE posed security risks to the U.S. Various parts of the Trump administration have also suggested banning U.S. pension funds and even private investors from putting money into Chinese companies, as well as banning Chinese companies from listing on American markets.

Speculation about a U.S.-led financial war on the one hand, and the booming markets of China on the other, is helping to shape new hopes and fears on both sides of the Pacific: that China will overtake the U.S. as a global financial center.

When granddaddy invites you to a late-night meeting

Some have argued that China’s regulators were right to call a halt to Ant Group’s IPO, because it presented a systemic risk to China’s financial system, or because the company’s disclosures were incomplete, and for other sensible reasons. But even if the decision to call off the IPO was entirely rational and in the interests of Chinese citizens, the fact remains that we do not know what happened. We do know that the government made a point of publicly humiliating Jack Ma by calling him late at night for a surprise meeting with four regulatory agencies, and announcing it loudly and clearly via WeChat (in Chinese). The next day came the follow-up, also late at night, when the Shanghai Stock Exchange announced the suspension (in Chinese) of Ant’s IPO.

The surprise late-night meeting and announcement are classic Party tactics that communicate a power relationship to the people forced by a late-night phone call to a meeting, and to everyone who reads about their meeting on their smartphone the first thing the next morning. The power relationship is clear. As an old Beijinger friend of mine often says: “China only has one granddaddy; everyone else is just a little grandkid” (中国只有一个爷爷,剩下的都是孙子 zhōngguó zhǐ yǒu yí gè yéye, shèngxià de dōushì sūnzi).

The thing is, granddaddy is generally a competent manager of the economy. And it’s possible to come to a harmonious understanding with him, even after you make mistakes. After state media criticized ByteDance (owner of TikTok) for political problems at its jokes and humor app Nèihán Duànzǐ 内涵段子, founder and CEO Zhāng Yīmíng 张一鸣 was forced to write an abject public apology. His business has gone on to prosper.

So the result of the Party’s way of managing tech companies is unlikely to end in their demise. And there probably won’t be a noticeable slowdown in innovation and new company formation by ambitious Chinese digital entrepreneurs. But the lack of transparency in the Chinese system, the knowledge that you might get a late-night phone call anytime, even at the peak of your success, means that Chinese businesspeople will continue to seek to raise capital in markets where the regulations are at least transparent.

When (or if) the Ant Group IPO happens, it may be seen by many as the end of an era of American financial dominance. But it would be premature to write Wall Street’s obituary. China’s markets and regulators have a long way to go when it comes to predictability and the rule of law.

Wall Street’s not dead yet.

Despite the trade war, Trump’s hostile rhetoric, and many other headwinds, China-based companies have raised $9.1 billion by listing on U.S. markets this year so far, more than in any year since 2014, the year Alibaba listed. We can expect this trend to continue. Unless, of course, the U.S. decides to shoot itself in the foot and completely exclude Chinese companies from its financial system, even if they do not present security risks or deserve sanction for human rights abuses.

Note: “After state media criticized ByteDance (owner of TikTok) for political problems at its jokes and humor app Nèihán Duànzǐ 内涵段子” was amended; it originally read, mistakenly, “at its news app.”