Asia-Pacific economic explainer: How the China-friendly RCEP arose after the U.S. abandoned TPP

What was the impetus for RCEP, the largest free trade agreement in the world? Was it a win for China? Why should the U.S. care about this and other Asia-Pacific trade deals? You have questions, we have answers.

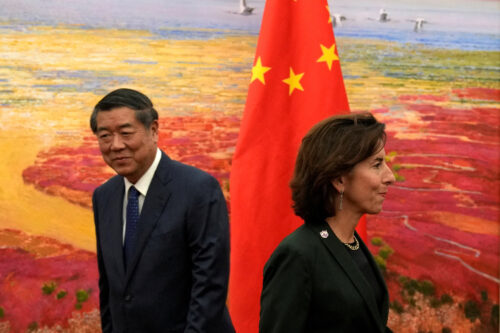

When the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) was signed on November 15 by 15 countries — China, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, Japan, and the 10 member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations countries (ASEAN) — it marked the largest free trade agreement in history, projected to add $500 billion to world trade by 2030.

Observers quickly argued that this affirmed a newfound leadership role for China, concomitant with the decline of U.S. influence in the Asia-Pacific region. But how true is that?

This piece takes a closer look at RCEP and a similar regional trade deal, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) — which formed after President Donald Trump pulled the U.S. out of the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in January 2017.

By looking at these deals, we can see how China stands to make substantial economic and geopolitical gains in the Asia-Pacific region and the international community writ large, particularly in the absence of the United States.

![]()

What was the impetus for RCEP? Who was behind its creation?

Created by ASEAN, the impetus behind RCEP was, quite simply, to enhance regional economic engagement and promote cooperation between ASEAN member states and other external partners.

The origins of the trade pact date back more than two decades, to a study of a potential free trade agreement between ASEAN, China, Japan, and Korea (collectively known as ASEAN+3) in December 1997. This study initiated another study process for an ASEAN+6 agreement that included Australia, India, and New Zealand. Upon the conclusion of both study processes in 2011, ASEAN conceptualized RCEP, which officially launched in November 2012 at the ASEAN Summit in Cambodia by the leaders of 16 participating countries. While part of the incipient bloc, India later opted out in 2019 over concerns that the treaty did not do enough to curb a potential surge of cheap Chinese imports.

RCEP was based upon the premise that it would center around an ASEAN framework. The treaty’s guiding principles assert that “negotiations for RCEP will recognize ASEAN Centrality.” This is important to note, because RCEP is often inaccurately considered to be “China-led.”

The initial objective of RCEP negotiations was to “achieve a modern, comprehensive, high-quality, and mutually beneficial economic partnership agreement among the ASEAN Member States and ASEAN’s [free trade agreement] partners.” Put another way, ASEAN sought to combine the various free trade agreements with the five non-ASEAN states — China, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, and Japan — into a single framework.

Why is RCEP significant?

Many reasons — here are a couple.

First, RCEP is a historic achievement. The treaty comprises 2.3 billion people — more than any previous regional free trade agreement in history. The RCEP trade bloc accounts for a whopping 29 percent of global gross domestic product, exceeding that of both the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement and the European Union. In addition, it bolsters China’s status as both a nascent champion of multilateralism and the preeminent economic power in the Asia-Pacific region. It represents a symbolic rebuke to the protectionist tide that has swept across the world since 2016.

Second, as China has increasingly moved to set regional and international trade rules without the influence of the United States, treaties like RCEP that favor Chinese economic activities — including lower labor standards, lower environmental standards, and fewer constraints on the influence of state-owned enterprises — might represent the future of multilateral trade. For example, RCEP’s provisions regarding ecommerce and digital trade present somewhat of a preview to the World Trade Organization’s impending Joint Statement Initiative (JSI) on Electronic Commerce, which is currently undergoing negotiations involving 86 WTO member states that represent over 90 percent of world trade.

What exactly does RCEP do — and what are its limitations?

The treaty eliminates manifold tariffs on imports within 20 years and establishes common standards across ecommerce, trade, and intellectual property. For example, 86 percent of industrial goods shipped to China from Japan will become tariff-free. Eventually, RCEP promises to remove up to 90 percent of the tariffs on imports and facilitate augmented trade between its member states.

However, it is not a complete free trade agreement: It formalizes the removal of tariffs on many items already exempted under other free trade deals and has a massive loophole that allows member countries to retain tariffs on industries they deem to be particularly important or sensitive. In this sense, RCEP aims more to codify existing trade structures between countries than to reshape and transform them. Former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has criticized RCEP as “a really low-ambition trade deal.” Notably, the treaty has linked nation-states that enjoy historically tense diplomatic relationships, particularly China and Japan.

One of the most interesting aspects of RCEP is its “rules of origin” provision, which specifies where a product must come from to enjoy the tariff preferences of the agreement. Compared to most other major trade agreements, the terms are rather lenient. According to this provision, just 40 percent of a product must be produced by a country in the RCEP region to receive preferential treatment; 60 percent can originate in the United States or elsewhere in the world. According to Mary Lovely, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, RCEP’s broader standards might incentivize multinational corporations to keep jobs in Asia rather than relocate them to North America.

“Lower tariffs within the region increase the value of operating within the Asian region, while the uniform rules of origin make it easier to pull production away from the Chinese mainland while retaining that access,” Lovely explained.

How accurate is it to say that RCEP is the Asia-Pacific region’s follow-up to the U.S.’s botched attempt to organize trade partners around the TPP?

It’s a bit more complicated than that, but essentially yes. U.S. officials under Barack Obama’s administration viewed the Trans-Pacific Partnership as the primary foundation of a strategic “pivot” to East Asia, affirming America’s status as a reliable diplomatic and economic partner in the region. It was on track to pass until support for the trade pact within the U.S. crumbled. While it was Trump who officially withdrew the U.S. from the TPP, it is important to remember that U.S. opposition to the treaty was bipartisan by 2015. Hillary Clinton, who previously referred to the TPP as the “gold standard,” broke with the Obama administration and came out against the agreement in October 2015.

Once the U.S. removed itself from TPP negotiations, the remaining 11 signatories (also known as the TPP-11) continued talks, which ultimately resulted in the ratification of a different deal in March 2018 — the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Of course, the primary reason the CPTPP passed but TPP did not was the dramatic shift in U.S. international trade policy. But the CPTPP also passed more easily because it removed the stricter copyright and patent provisions that the U.S.-led TPP previously included.

Can you explain the CPTPP? Who are the signatories?

Signed in 2018, the CPTPP is a free trade agreement between 11 countries — Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, New Zealand, Singapore, and Vietnam — that has been touted as a “next-generation” trade agreement. This reputation stems from its innovative provisions that prohibit customs duties on electronic transmissions and exhort member states to abide by internationally agreed-upon labor laws and environmental commitments. While both CPTPP and RCEP harbor similar global aspirations to expand market access and promote private investment, the CPTPP sets markedly stricter labor, environmental, and governance standards.

Since its signing, the CPTPP has yielded somewhat mixed economic results for its member states. While Australia has experienced a notable increase in trade with CPTPP partners, Japan’s trade deficit with Australia, Vietnam, and Canada has expanded. In the future, several other nation-states might potentially join the trading bloc, including Taiwan, Thailand, and Indonesia. China has also expressed interest. Yet the thus-far ambivalent results of the CPTPP, two years after its implementation, suggest that countries would do well to temper their expectations for what RCEP will accomplish.

So China is not part of CPTPP.

Australia and Chile have previously welcomed China’s participation in the CPTPP, but the PRC exhibited little interest in joining due to domestic and economic concerns. The CPTPP’s stringent requirements would markedly disrupt China’s economic reforms back home. In addition, the treaty’s stipulations regarding state-owned enterprises (SOEs) present a notable obstacle. According to the CPTPP’s “competitive neutrality approach,” both state-owned and private enterprises must compete on a level playing field, which China has not been willing to commit to.

However, this may not be the case for long. Upon completion of RCEP negotiations, Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 announced at a November 20 APEC Summit that China will “favorably consider” joining the CPTPP, a sentiment that was reiterated upon the December 17 conclusion of the Central Economics Works meeting. China also recently finalized a major investment agreement with the European Union. Recently, it seems the PRC has increasingly moved to seize the mantle of global trade leadership abdicated by the U.S. under Trump.

“The RCEP allows China to cast itself as a champion of globalization and multilateral cooperation,” noted Gareth Leather, a senior Asia economist at Capital Economics. “It also puts China in a better position to determine the rules governing regional trade.”

What would happen if China joined CPTPP?

Let’s slow down a bit. It is certainly plausible, though the process would not be entirely seamless.

If China joined the CPTPP, it would likely need to undergo significant internal economic reforms. To abide by the treaty’s SOE stipulations and restrictions, China would need to eliminate all anti-competitive subsidies provided by state-backed financial institutions. In addition, China must commit to measures that promote increased transparency, environmental protection, anti-corruption, and intellectual property protection.

Furthermore, China must not only pledge to adopt such stringent standards but also successfully convince other CPTPP member states of its sincere intentions. The treaty contains an open accession clause, which essentially states that it is open to any state that existing parties deem worthy of admission: All decisions are rooted in consensus, and each individual existing state has the right to veto China’s membership.

To be clear, China’s accession to the CPTPP would bring immense financial benefits for itself, other member states, and the world economy. At present, the treaty adds about $147 billion in annual global income gains — and that’s without the U.S. and China, the world’s two largest economies. China’s addition to the treaty could quadruple this amount. In fact, China would provide twice as many benefits to CPTPP members as it receives.

How does China view RCEP?

China initially showed little interest in the various ASEAN-led study processes that preceded RCEP — until Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda’s pronouncement at the 2011 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) of Japan’s interest in joining the U.S.-led TPP, which deliberately excluded China.

China joined the RCEP trading bloc, which officially launched in 2012, as negotiations for the TPP continued to make rapid progress. It has since then viewed RCEP in a more geopolitical light — as a stratagem to counteract growing U.S. influence in the Asia-Pacific. Indeed, Boston University’s Min Ye writes that China’s abrupt policy shift “was entirely due to TPP.”

Today, senior Chinese officials back ASEAN leadership and support RCEP as a counterweight to the CPTPP. Upon assuming office in March 2013, Wáng Yì 王毅, China’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, referred to China-ASEAN as a “big family” and stated that ASEAN represented one of China’s key diplomatic priorities.

Did China support the creation of RCEP because it didn’t have a seat at the CPTPP table?

Sort of…though not exactly.

Although China stands to be the largest single beneficiary of RCEP, China did not create the pact — ASEAN did. In fact, domestic support for RCEP among scholars and analysts in China is somewhat mixed. Some have expressed discontent with the ASEAN-led regionalism in RCEP, which arguably subordinates China to ASEAN leadership.

However, by virtue of its economic and international heft, China has taken on a leadership role and largely dominates the RCEP narrative. And China’s interest in the trade bloc primarily grew out of its inability to join the U.S.-led TPP — now the CPTPP. This simultaneously entwined with China’s ardent desire to assert its own geopolitical footprint and combat the rising regional influence of the United States.

Would it be fair to say that RCEP was a win for China?

Yeah, we can say that.

According to estimates from the Peterson Institute for International Economics, China will be the biggest single economic beneficiary of this treaty, gaining over $100 billion in added income.

The treaty will enable China to both strengthen economic ties and relations with its neighbors in the Asia-Pacific and set regional trade rules without the influence of the United States. The agreement will open vibrant developing markets in nascent economies like Thailand and Vietnam, and all across Southeast Asia. In addition, the agreement can help China counteract the effects wrought by the U.S.-China trade war: finding duty-free imports from RCEP partners to replace U.S. imports now subject to tariffs under the Trump administration. This proves particularly significant given President-elect Joe Biden’s comment that these tariffs will not be immediately lifted upon his inauguration. China can also utilize the RCEP to increase the exchange of high-tech equipment and know-how with South Korea and Japan to pursue its Made in China 2025 policy initiative.

Why should the U.S. care about these regional trade deals?

Because the U.S. stands to fall behind and cede significant influence to China in the Asia-Pacific region. Beyond commercial benefits for American workers and producers, regional trade pacts symbolize and reinforce U.S. commitments to its allies. For example, the U.S.-Israel free trade pact signed in 1985 underpins the U.S.-Israel relationship today.

What will President-elect Biden do?

It’s hard to say. He has remained relatively mum on the issue of joining either RCEP or CPTPP, ever wary of persistent domestic anti-trade sentiment in the United States. Instead, Biden said he will reveal a detailed trade plan on January 21 because he has not yet assumed office “and there’s only one president at a time.” For now, the world must wait for America’s next move on multilateral trade in the Asia Pacific.

What’s at stake here for the U.S.?

America retains a strong presence in the Asia-Pacific, and the Biden administration can certainly take steps to counteract the effects of Trump’s “America First” isolationism. However, doing so will require political skill and patience, and it will not be easy.

The cards of public opinion remain stacked against a reinvigorated international trade presence for the U.S. “Americans generally think trade is good for the country, but they are not sure it’s good for them personally,” Pew Research Center’s Bruce Stokes said. “Psychologically, people need something or someone to blame for their misfortune and trade is a handy bogeyman, with a kernel of truth to the fact that trade has destroyed many livelihoods.”

One formidable obstacle that Chinese leaders must overcome in their quest to expand Beijing’s international influence under Xi remains the high levels of public distrust and unfavorable views toward China among developed, democratic nations. According to a recent survey, roughly half of respondents from Australia and Japan — two preeminent RCEP member states — said they had “no confidence at all” in Xi’s leadership. 81 percent of Australian survey respondents said they viewed China unfavorably, a drastic uptick of 24 percentage points from last year. In the battle to win hearts and minds, China thus far continues to fall somewhat short.

Yet goodwill toward America will not endure unless Biden actively shores up U.S. commitments to Asia-Pacific allies and convinces fellow world leaders that the Trump administration was a short-term anomaly — not a long-term political trend. To do so, Biden must first rejoin the Paris Climate Accord, which he has already promised to do on his first day in office, asserting America’s reinvigorated commitment to internationalism and multilateralism. He must then overcome domestic political opposition from the progressive left and the right — difficult albeit not insurmountable hurdles — to join the CPTPP and ensure the U.S. does not remain left behind on international trade. Without a doubt, the Biden administration’s path ahead will not be easy, but restoring America’s influence and status in the Asia-Pacific requires nothing less.