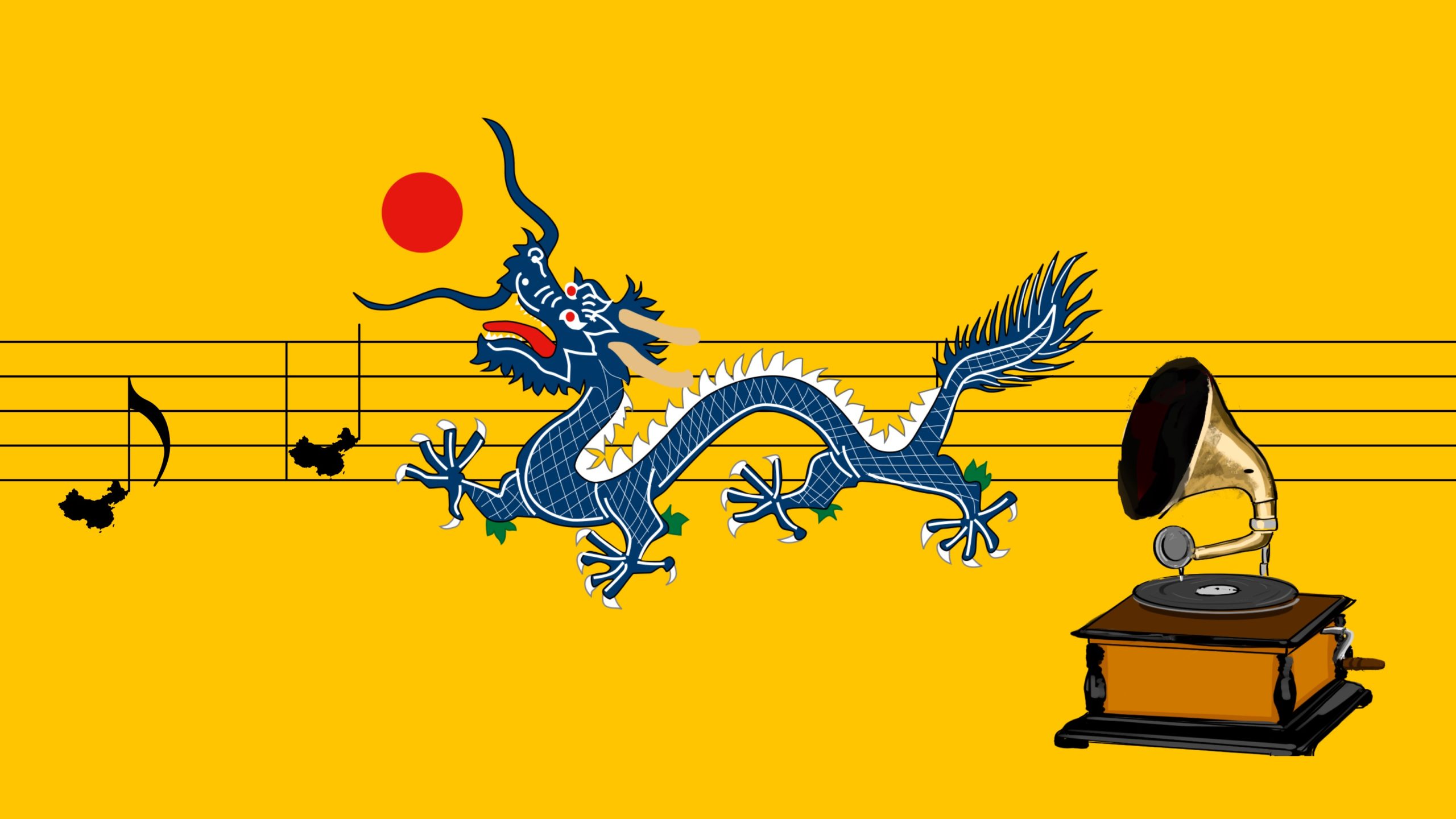

One song under Heaven: A history of China’s national anthems

A survey of nearly 150 years of Chinese history through the country's official and unofficial national anthems.

“Arise, ye who refuse to be slaves!” Thus begins “March of the Volunteers,” China’s current national anthem. But before this song, many others sought to be the one that aroused the spirit of the Chinese people. Songs like “China Heroically Stands in the Universe,” “Song of Five Races Under One Union,” and “Song to the Auspicious Cloud” were once sung by millions of people, carefully crafted to inculcate a sense of the country’s identity, vision, and mission.

An anthem tells the story of a nation. This article will take you on a tour of China’s anthems, and in the process tell a story of China’s changes.

Jump to:

Pu Tian Yue (1879-1896)

Tune of Li Zhongtang (1896-1906)

Praise the Dragon Flag (1906-1911)

Cup of Solid Gold (1911-1912)

Song of Five Races Under One Union (1912-1913)

Song to the Auspicious Cloud, v1 (1913-1915)

China Heroically Stands in the Universe (1915-1921)

Song to the Auspicious Cloud, v2 (1921-1928)

Three Principles of the People (1928—)

The Internationale (1931-1937)

March of the Volunteers (1949-1978)

The East is Red (1966-1978)

March of the Volunteers (1978-1982)

March of the Volunteers (1982—)

1879-1896

Pǔ Tiān Yuè 普天乐

Unofficial anthem by Zeng Jize

Roughly translated as “Song to the Whole World,” Pu Tian Yue was never officially recognized by the Qing dynasty (1644-1912) as a national anthem. Rather, the Qing dignitary Zéng Jìzé 曾纪泽 penned it when he was caught off guard during his stint as a diplomatic envoy in Europe between 1879-1885. While representing the Qing government under the Guāngxù 光绪 emperor at an international convention, he discovered that protocol dictated a “national anthem” be played by each nation in attendance.

Pu Tian Yue has been regarded as the country’s first national anthem, however unofficial. That is, this is what China put forth to foreign powers as its representative song. Unfortunately, there are no surviving recordings of the lyrics, which seem to have been lost to time. The above is the earliest known surviving version of the tune, recorded by a military band in Camden, New Jersey, in 1914.

1896-1906

Tune of Li Zhongtang (李中堂乐 lǐ zhōngtáng yuè)

Unofficial anthem by Li Hongzhang

Lǐ Hóngzhāng 李鸿章 found himself in a similar situation as Zeng Jize on his famous tour of Europe and America in 1896. He was one of the most distinguished politicians and commanders of his generation, having passed the imperial exams with marks, suppressed one of the bloodiest uprisings of the 1800s (the Taiping Rebellion), and pushed China to modernize its army and navy through the Self-Strengthening Movement in the waning years of the Qing. Li employed a poem by the Tang dynasty’s Wáng Jiàn 王建 as the lyrics to represent him at the courts of the foreign devils. As this was not an official anthem in the eyes of the dynasty, it was named “Tune of Li Zhongtang” — Zhongtang being a Qing bureaucratic title often translated as “viceroy” or “grand secretary.”

The lyrics revere classic dynastic symbolism — from the Forbidden City to the emperor as the son of heaven — though the song is still missing the trappings of a traditional national anthem. Being the one-time commander of the ill-fated Beiyang Fleet, Li had a similar anthem made for the fleet using the same melody.

1906-1911

Praise the Dragon Flag (颂龙旗 sòng lóng qí)

Unofficial / temporary anthem of the Qing dynasty

After the disaster of the Boxer Rebellion, the need for modernization was painfully clear. China’s self-strengtheners, borrowing from the blueprints of Western powers and Japan, argued that the dynasty should have its own national anthem. In 1906, “Praise the Dragon Flag” was created as an anthem to the Qing armed forces, created by the Department of the Army, and was installed as a “temporary national anthem” (代国歌 dài guógē). In the lyrics, the contours of a typical anthem emerges. The insertion of patriotic phrases such as “sing our empire’s song” (唱我帝国歌 chàng wǒ dìguó gē) should be noted as a foreign inspiration.

1911-1912

Cup of Solid Gold (巩金瓯 gǒng jīn’ōu)

First official anthem of the Qing Empire

Finally, on October 4, 1911, “Cup of Solid Gold” was adopted as the first official anthem of the Qing dynasty. The song was short lived, as a mere six days later the Xinhai Revolution began, causing the collapse of dynastic Chinese rule within months. The song was never performed publicly, but it still has a significant claim to fame as the first official national anthem on the Chinese subcontinent.

The melody for “Cup of Solid Gold” was written by Manchu nobleman Pǔtóng 溥侗, who was a direct descendant of the Daoguang Emperor. It was inspired by Peking Opera, using a compilation commissioned by the Emperor Kangxi to underline the continuity of the Manchu dynasty. The lyrics, although written by the reform scholar Yán Fù 严复, were a gallery of imperial self-praise, including lines like: “As long as the Qing rules, our empire is emblazoned by light.”

The “golden cup” (金瓯 jīn’ōu) refers to a golden sacrificial vessel that the emperor would use at palace rituals to represent the dynasty. The first character in the song title, gǒng 巩, means “strengthen” or “consolidate”; an alternate translation could therefore be “Strengthening the Dynasty.” A golden vessel covered with precious stones called “the cup of eternal solid gold” still exists, and is on display at the palace museum in Beijing.

1912-1913

Song of Five Races Under One Union (五族共和歌 wǔ zú gònghé gē)

Provisional anthem of the Republic of China

After the provisional government of the Republic of China was established in Nanjing, Sun Yat-sen (孙中山 Sūn Zhōngshān) was adamant about China having its own national anthem. Cài Yuánpéi 蔡元培, later president of Peking University and a prominent person in the May Fourth Movement, appealed to the public to send possible entries for anthems.

Shén Ēnfú 沈恩孚 and Shén Péngnián 沉彭年 released a draft of “Song of Five Races Under One Union” in a newspaper, and it was picked up and adopted as a temporary anthem during the presidency of Sun and the first year of the Republic. The “five races” refer to the Han, Manchus, Mongols, Hui, and Tibetans. The lyrics try to capture the zeitgeist of reform and revolution. Interestingly, the U.S. and Europe make cameos in the lyrics.

1913-1915

Song to the Auspicious Cloud (卿雲歌 qīng yún gē), version 1

Provisional anthem of the Republic of China

In this anthem, the provisional government reached back into the vast catalogue of China’s culture to borrow a song from the ancient Emperor Shun, recorded in the Book of Documents (尚书 shàng shū). The song was said to have been written by the emperor when he handed over the dynasty to Yu the Great, a legendary emperor who tamed China’s floods. The auspicious cloud is a symbol of heaven and good fortune, essentially representing the hope of stability and prosperity.

The text is identical with the original, save for the last line, which was the only addition to the 1913 version: “Time has changed, the whole nation is no longer owned by one person.” A zinger to the Qing, or perhaps meant as a warning to Yuán Shìkǎi 袁世凯, who wanted to be emperor. The melody was composed by Belgian composer and Esperantist Jean Hautstont, who was active in Belgian anarchist circles.

1915-1921

China Heroically Stands in the Universe (中国雄立宇宙间 Zhōngguó xióng lì yǔzhòu jiān)

Official anthem of the Republic of China

Modified as the official anthem of the Empire of China (1915-16)

Modified again as the official anthem of the Republic of China (1916-21)

As Yuan Shikai took over the position of president from Sun Yat-sen, the national anthem changed again. It was a tumultuous time for the national song, as it changed three times within two years. The above version, with lyrics by Yìn Chāng 廕昌 and melody by Wáng Lù 王露, was issued by the Rituals Regulations Office and adopted as the official national anthem in 1915. It did not last long, as by December 1915, Yuan made the bold move of declaring himself emperor.

In keeping with the new state’s ideals, Yuan kept an anthem for the empire — the same song — but replaced the nation-state mentions in “Five Races Under One Union” with a reference to ancient Chinese imperial succession. But both Yuan’s empire and his anthem were short-lived. Provincial strongmen and intellectuals turned their backs on Yuan’s megalomaniacal dreams, and after mere months, Yuan was dead. China then slid into its Warlord Era.

With Yuan gone, the leader of the powerful Zhili clique in northeast China, Zhāng “The Tiger of Mukden” Zuòlín 张作霖, took over. China was split into factions and groups under local warlords and strongmen. China lay divided, and the leaders in Beijing — or Beiping, as it was known at the time — represented China to the world. Having done away with the inconveniences and long-drawn processes of democracy, Zhāng Zuòlín took the liberty of writing his own lyrics for a new national anthem:

China heroically stands in the universe,

Ten thousand years!

Defend the people with no bias.

Various industries are prosperous and the nation is solid.

Peaceful and tranquil time within four seas.

Ten thousand years!

中华雄立宇宙间

Zhōnghuá xióng lì yǔzhòu jiān

万万年!

wàn wàn nián

保卫人民中不偏

bǎowèi rénmín zhōng bùpiān

诸业发达江山固

zhū yè fādá jiāngshān gù

四海之内太平年

sìhǎi zhī nèi tàipíng nián

万万年!

wàn wàn nián

Zhang took serious liberties, including departing from the themes in the previous two versions. A focus on industry is back, and rather than playing it fancy, Zhang used a crowd-pleaser in the final line: wàn wàn nián 万万年 — “ten, ten thousand years!”

1921-1928

Song to the Auspicious Cloud (卿雲歌 qīng yún gē), version 2

Official anthem of the Republic of China

Perhaps feeling the heat of the May Fourth Movement, Duàn Qíruì 段祺瑞, local Beiping strongman and leader of the provisional government, set up the National Anthem Research Committee to change the tune of the nation once again. The committee returned with a near-copy/paste of the first “Song to the Auspicious Cloud,” leaving out a line that challenged strongman-style rule — “Time has changed, the nation is no longer owned by a single person” — and instead keeping it short and sweet, repeating the stanza referring to the sun. (The sun was, after all, on the flag of the republic.) By presidential decree No. 759, Duan Qirui made this the anthem of the republic in 1921.

1928 — present

Three Principles of the People (三民主义 sān mín zhǔyì)

Official anthem of the Republic of China

After the Northern Expedition ended in 1928 — a two-year military campaign against warlords — the anthem was again changed to get away from the taint of the era. “Three Principles of the People” was adopted as the Kuomintang (KMT) party song in 1928 and used in place of a national anthem. KMT leaders seized on a speech delivered by Sun Yat-sen at the Whampoa Military Academy in 1924 as a fitting basis for the anthem, honoring the “father of the country” (国父 guófù) and including the general political principles of the KMT. It was used as a temporary national anthem before it was adopted as the official national anthem of the ROC in 1937, and it remains the party anthem of the KMT in addition to the national anthem of Taiwan.

The song is regularly updated by the office of the president of the Republic of China, but remains controversial — some Taiwanese see it as a symbol of the military dictatorship under the KMT. “Three Principles of the People” also served as the anthem of the Japan-supported collaborationist government under Wāng Jīngwèi 汪精卫.

1931-1937

The Internationale (国际歌 guójì gē)

Official anthem of the Chinese Soviet Republic

The 1927 Shanghai massacre saw Chinese Communist Party members violently purged by the KMT. In 1931, Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 and the Communists founded the Chinese Soviet Republic (CSR) (中华苏维埃共和国 zhōnghuá sūwéi’āi gònghéguó), effectively marking the start of the Two Chinas. The anthem chosen for the CSR was, in good Communist style, “The Internationale,” written by French anarchist Eugène Pottier in 1871. The song remained the anthem of the CSR throughout the 1930s until the formation of the Second United Front in 1937.

1949-1978

March of the Volunteers (义勇军进行曲 yìyǒngjūn jìnxíng qǔ)

Provisional anthem of the People’s Republic of China

The Chinese playwright Tián Hàn 田汉 could not have foreseen the impact of the few lines he wrote in 1934, which became synonymous with the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. Originally written as a poem inspired by “The Internationale,” the lyrics to “March of the Volunteers” were adapted to the 1935 production Children of Troubled Times (风云儿女 fēngyún érnǚ), by Shanghai-based Diantong Film Company, with music by the composer Niè Ěr 聂耳. It was recorded in the famous Pathé recording studio in Shanghai.

Although the movie did not fare well and Diantong was forced to close the same year, “March of the Volunteers” became a smash hit in war-torn China. It was sung by Nationalists and Communists alike, and was translated into English by the American Paul Robeson, who corresponded with Tian Han to make the English version. First known in English as “Chee Lai!” — the transliteration of the song’s first two words, qǐlái 起来 — it became a foreign anthem of sorts for drumming up support for the Chinese war effort. Soong Ching Ling (宋庆龄 Sòng Qìnglíng) wrote the preface for the English album recording, and it was even featured in the film series Why We Fight, about the war in China. All the money Robeson raised was donated to the Chinese war effort through Tian Han.

As the Chinese civil war came to a close, the question of what should be the anthem of the soon-to-be-founded People’s Republic of China was raised in early 1949, and 694 songs were collected as possible entries. “March of the Volunteers” was an early favorite, both owing to its general popularity among the people and its theme of struggle. The line “the Chinese people face their greatest peril” caused some trouble, since the “peril” that Tian Han referred to had by then been done away with. To this, Zhōu Ēnlái 周恩来 allegedly noted, “We still have imperialist enemies in front of us. The more we progress in development, the more the imperialists will hate us, seek to undermine us, attack us. Can you say that we won’t be in peril?”

The anthem was adopted as the provisional anthem played when Mao stood atop the rostrum of the Gate of Heavenly Peace to declare the founding of the P.R.C. on October 1, 1949. But trouble would befall the song and its creator. During the Cultural Revolution, Tian Han was one of the first targets of scathing public criticism in Chinese newspapers because of a 1961 play he had authored, critical of the chairman and the CCP leadership. Shortly thereafter, “March of the Volunteers” was banned, and “The East is Red” (东方红 dōngfāng hóng) was sung in its place. Tian Han was imprisoned in a facility operated by security czar Kāng Shēng 康生, where he died in 1968, charged as a counter-revolutionary. His song’s melody was played during National Day parades beginning in 1969, but the lyrics weren’t resuscitated until the mid-1970s.

Watch and listen to different recordings of “March of the Volunteers” below (my favorite is the 1959 version).

1966-1978

The East is Red (东方红)

De facto anthem of the P.R.C. during the Cultural Revolution

“The East is Red” started out as a popular song in the revolutionary capital of Yan’an, written by the Shaanxi farmer Lǐ Yǒuyuán 李有源. The melody was adopted from local Shaanbei folk songs whose lyrics changed depending on the singer. Think of the music from Yellow Earth (黄土 huángtǔ), with Chinese cymbals and flutes aplenty.

Many local songs, such as “White Horse Tune” (白马调 báimǎ diào) and the folk song “Sesame Oil” (芝麻油 zhīmayóu), were written using the same melody. Li Youyuan allegedly said that the inspiration for “The East is Red” came to him when he saw the sun rise over the loess hills of northern Shaanxi. Originally the song was a tribute to Communist heroes of the Yan’an soviet who were killed in action in the late 1930s, but Mao’s name was inserted into the song while the Communist leadership was still in Yan’an.

The song lost some of its popularity after 1949, but it was picked up again as the cult of Mao grew. After Tian Han was purged, a full-on East is Red craze followed. During the Cultural Revolution, from 1966-1976, “The East is Red” was played over loudspeakers in villages, townships, and farms across China at dawn and dusk. 2,000-year-old bells from the Warring States Period chimed the song every day over the Central People’s Broadcasting Station. A musical by the same name graced Chinese silver screens in 1965, and the title of the song became a favorite name for anything and everything, from counties (in 1967, a county in Xinjiang bordering Kyrgyzstan was renamed the “East is Red Commune”) to steam trains to tractors. China’s first satellite was not only named East is Red 1, but also beamed “The East is Red” as its first signal back to Earth in 1970.

By the end of the Cultural Revolution, perhaps people were burnt out by this tune. “March of the Volunteers” took over again as the national anthem. Still, “The East is Red” is played today, from Chinese landmark buildings such as the British Customs building in Shanghai and the Beijing Train Station. In a 2009 survey, it was voted as the most patriotic Chinese song in an online survey.

1978-1982

March of the Volunteers

Provisional anthem of the People’s Republic of China

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G35xgx0IWrE

As the trials against the Gang of Four were broadcast on Chinese television in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution, “March of the Volunteers” regained its status as the national anthem. Mao’s name was inserted in the song before being taken out in 1982. It is also notable that the first two words of the anthem — an exhortation for the people to “Arise” — was changed to the words “March on” (前进 qiánjìn). Tian Han was also posthumously rehabilitated in 1979; Robeson continued to send royalties from the American recording of the song to Tian Han’s family after Tian’s death.

March on! Heroes of every race!

The great Communist Party leads us in continuing the Long March!

Millions with but one heart toward a Communist tomorrow

Bravely struggle to develop and protect the motherland.

March on! March on! March on!

We will for many generations

Raise high Mao Zedong’s banner! March on!

Raise high Mao Zedong’s banner! March on!

March on! March on! On!

1982 — present

March of the Volunteers

Official anthem of the People’s Republic of China

By 1982, “March of the Volunteers” had been restored to its original post-1949 lyrics and melody, and it’s this version that was made the official national anthem of the P.R.C. It carries the legacy of China’s struggle — and for a whole generation, the struggle against the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. In 2004, the song was elevated even further, as the Chinese constitution was amended to include “March of the Volunteers.” The Chinese central government regularly updates the entry with music sheets and videos of the national anthem being performed (the latest update from January 4, 2021).

Here is the version from October 1, 2019, the 70th anniversary of the P.R.C.:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L_K_sbfh90o

The lyrics:

Arise, ye who refuse to be slaves!

With our flesh and blood, let us build a new Great Wall!

As China faces its greatest peril

From each one the urgent call to action comes forth.

Arise! Arise! Arise!

Millions of but one heart

Braving the enemies’ fire! March on!

Braving the enemies’ fire! March on!

March on! March, march on!

起来!不愿做奴隶的人们!

Qǐlái! Búyuàn zuò núlì de rénmen

把我们的血肉,筑成我们新的长城!

Bǎ wǒmen de xuèròu, zhùchéng wǒmen xīn de chángchéng

中华民族到了最危险的时候,

Zhōnghuá mínzú dàoliǎo zuì wēixiǎn de shíhòu

每个人被迫着发出最后的吼声。

Měi ge rén bèipòzhe fāchū zuìhòu de hǒushēng

起来!起来!起来!

Qǐlái! Qǐlái! Qǐlái!

我们万众一心,

Wǒmen wànzhòngyìxīn

冒着敌人的炮火,前进!

Màozhe dírén de pàohuǒ, qiánjìn

冒着敌人的炮火,前进!

Màozhe dírén de pàohuǒ, qiánjìn

前进!前进!进!

Qiánjìn! Qiánjìn! Jìn!

Appendix: Other Songs

Anthem of Bogd Khanate (大蒙古国 dà ménggǔ guó), 1911-24

As the Qing dynasty fell, a group of Mongols declared their independence as the Bogd Khanate in Outer Mongolia. Attempts were made by successive governments during the Warlord Era to bring Outer Mongolia back to China, but the attempts were ultimately unsuccessful, as by 1924 a Leninist government had been installed by the Soviet Union.

How Great is Our China! (泱泱哉,我中華 yāng yāng zāi, wǒ zhōnghuá), 1912

With lyrics written by the Chinese intellectual Liáng Qǐchāo 梁启超, “How Great is our China!” made the rounds in intellectual and student circles in China in the 1910s. It was an optimistic reminder to the Chinese people of the potential for modernization. One stanza goes: “Britain and Japan, mere islands, still prosper.”

Mongol Internationale — the Mongolian Anthem, 1924-50

Not to be confused with “The Internationale” of 1871, Mongolia had its own Internationale written in 1924, complete with original lyrics, style, and melody.

Song of the National Revolution (国民革命歌 guómín gémìng gē), 1926

This was a popular tune among Chinese military leaders who had studied at Whampoa Military Academy in Guangdong — or, really, anyone who hated the Warlord Era, which is clear in the first verse:

Overthrow the foreign powers,

Eliminate the warlords;

The citizens strive hard for the revolution,

Jointly we struggle.

National Anthem of Manchukuo (满洲国国歌 mǎnzhōu guó guógē), 1933-42

The entry on this list with the most affluent use of glockenspiel is the National Anthem of Manchukuo, established under Puyi as a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria.

Anthem of Tibet – Gyallu – 西藏国歌 བོད་རྒྱལ་ཁབ་ཆེན་པོའི་རྒྱལ་གླུ།, 1950

This song was written in 1950. It is unclear when it was adopted by the Tibetan Government in Exile in Dharamshala, India, but it is often used by the “Free Tibet” movement.

Ode to the Motherland (歌唱祖国 gēchàng zǔguó), 1950

Sometimes referred to as “the second national anthem” of the P.R.C. — maybe occupying the same space as “God Bless America” currently does in the U.S. — “Ode to the Motherland” is often played after the March of the Volunteers.

Also see: