Convenience Bee — China’s first truly successful digital convenience store chain?

Convenience Bee says it is already profitable with more than 2,000 unmanned stores all over China. But can it raise enough cash to fund its ambitious expansion plans?

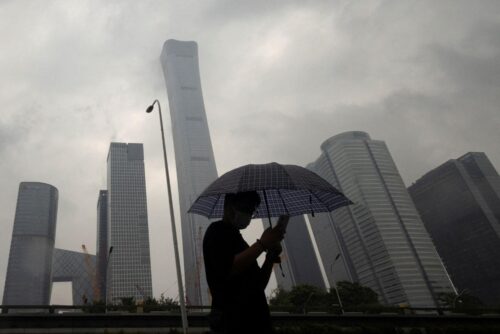

In China, a growing number of “new retail” giants such as Genki Forest and Shein are entering traditional industries and turbocharging their operations with technology. Convenience Bee (便利蜂 biànlì fēng), a popular convenience store chain modeled on Japanese brands like Lawson and FamilyMart, is slated to join their ranks.

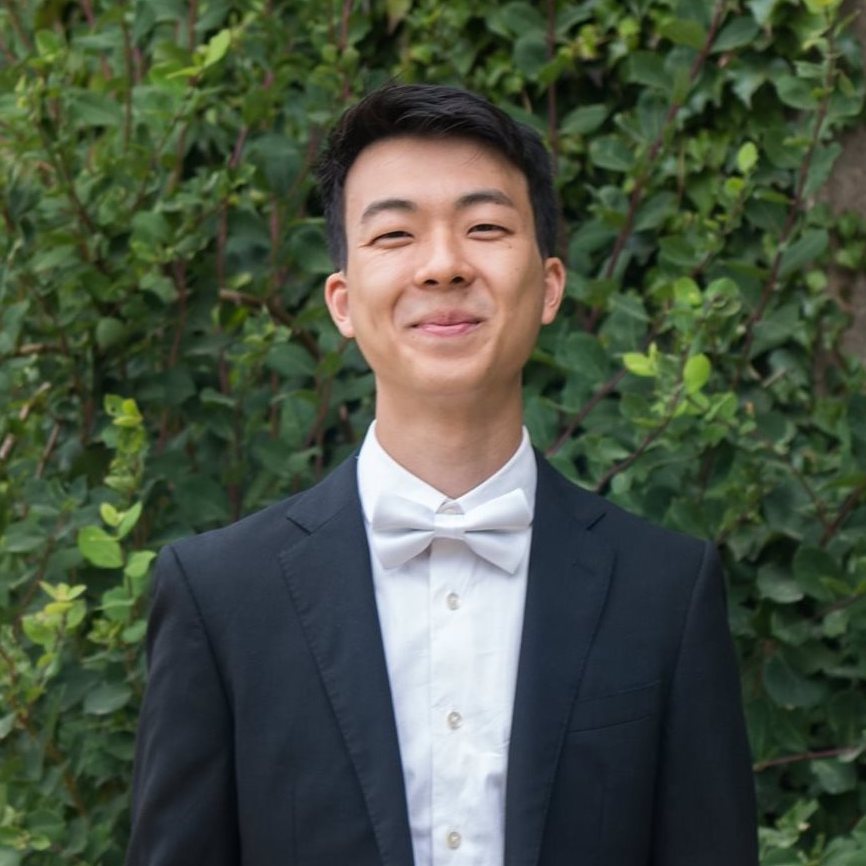

Founded in 2016, Convenience Bee is a China-based digital innovator of the Japanese-dominated convenience store industry. It “looks just like a fancier 7-Eleven from outside, but it’s actually closer to Luckin Coffee,” said Jerry Wang, the CEO of Haitou Global, an investment firm that invests in technology businesses around the world, “trying to revolutionize the traditional convenience store business using mobile payments, big data, and advanced retail technologies.” Convenience Bee stores are run by very few hands: Cameras and sensors detect what customers buy; electronic price tags update prices based on supply and demand in real time; and each store analyzes and iterates its product selection and prices based on market factors and user behavior. Technical staff — those who analyze the data — make up 60% of the company’s workforce.

The technical expertise points to a common trait among the new raft of successful retailers: their founders have tech backgrounds. Zhuāng Chénchāo 庄辰超, the founder, is the former CEO of Qunar.com, a travel-booking site similar to TripAdvisor. The transition from tech to traditional retail mirrors the stories of Táng Bīnsēn 唐彬森 of Genki Forest — games to beverages — and Xǔ Yǎngtiān 许仰天 (Chris Xu) of Shein — SEO to fashion. These founders did not start out as experts in their companies’ industries, but they came armed with the digital tools to disrupt them.

An object of Japanese envy

Lodged in the corner of an office building near one of Shanghai’s busy intersections is a Convenience Bee store with two employees. They wander, aimlessly, because the cashier register is gone: replaced by a touch screen device and two self-checkout counters. Employees can still check out customers, but “most use the self-checkout machine,” one employee said.

On the surface, Convenience Bee looks like a mirror image of Japan’s world-renowned convenience store setup: Light snacks and cosmetic products greet the customer upon entering, hot snacks roast near the counter, and mouthwatering beverages line the refrigerators near the back.

But recently, it was the Japanese that felt they had some catching up to do. In 2019, more than forty Japanese corporate representatives from industries such as software, IT, manufacturing as well as finance came to visit (in Chinese) a Convenience Bee store in China in collaboration with the Japan-China Economic Association.

“From a global perspective, It’s true that Japan’s convenience store industry is developing comparatively faster,” said Masaru Iwanaga, director of the Japan-China Economic Association, in an interview with Chinese media. “But Japan is not as fast as China in terms of digitization. So Japanese companies are really fascinated by the digitization model that can bring traditional convenience stores to the next level.”

According to Iwanaga, Convenience Bee’s innovations are a product of China’s unique environment, which brings together an already digitized economy with the newly imported mechanics of traditional businesses. The approach can seem like fundamental opposites. In the U.S. and Japan, legacy retail stores are mining the digital age for tech hints. In China, tech businesses are looking back at the older age for retail hints.

Convenience Bee is just the latest example of the “new retail” trend that is behind the growth of China’s unicorns. A tech company at heart with a retail specialty, it has automated many aspects of the traditional convenience store using automatic temperature controls, self-service check-outs, and QR codes on every price tag for quick inventory updates. Some companies such as Bingobox (缤果盒子), Xiao-e-Wei Shop (小e微店), and Yishi Box (怡食盒子) have experimented with fully automated convenience stores, but they have yet to reach scale and are still more of an experiment.

“Many unmanned retail companies started out as [speculative] investments,” said (in Chinese) Zhāng Yǒngbiāo 张勇标, who researches the convenience store business. “They didn’t consider how to sustain profitability and make money; they just wanted to make a splash and then cash out.”

A bull market for convenience stores?

Meanwhile, Convenience Bee is thriving. According to 36Kr (in Chinese), the company is already profitable, and its revenues are already comparable with the top three foreign convenience store brands in China: FamilyMart, Lawson, and 7-Eleven. If true, this is a remarkable performance: In April this year, Lawson announced that its China business was profitable for the first time in 2020, 25 years after it entered China. Both FamilyMart and 7-Eleven are only profitable in some regions.

Convenience Bee’s growth in operations is also dizzying: Since opening its first offline store in Beijing in February 2017, Convenience Bee has opened more than 2,000 stores in 20 cities in four years. Japanese-owned FamilyMart, by comparison, took 16 years to open 2,500 locations in China after opening its first store in Shanghai in 2004.

At the end of last year, Convenience Bee’s executive director, Xuē Ēnyuǎn 薛恩远, said that the company would go into “rapid expansion mode” in 2021, and that the number of Convenience Bee stores would exceed 4,000, an increase of 2,400 stores, by the end of this year. By the end of 2023, Convenience Bee plans to reach 10,000 stores (an average annual growth of 3,000), with half of them located in China’s second- and third-tier cities. This would make it one of the top five most accessible convenience stores in China.

The market is also on Convenience Bee’s side. China’s convenience store industry grew by 19% in 2018, with a market size of more than $30 billion. The top 100 convenience store chains grew by 21.1% year-on-year in 2018.

An IPO to fund breakneck growth

To fund this growth, Convenience Bee has been raising large amounts of money: It completed a financing round of $300 million led by Tencent in 2018. Last May, the company announced that it has already raised up to $1.5 billion from big-name investors. But to win the convenience store game, it needs even more money. Haitao’s Jerry Wang says, “It’s a promising business model. But it burns money fast. So public listing is a priority.”

According to the 36Kr report linked above, which was published in June, Convenience Bee was preparing an IPO in the U.S. with plans to raise $500 million to $1 billion, to be underwritten by Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, and CITIC Securities.

But after the Didi debacle last week, those plans may be on the back burner. Wang says a listing by the end of this year is “still possible and necessary” but may take place in Hong Kong, or in the U.S. after receiving approval from regulators. Paul Triolo of Eurasia Group, who recently co-authored a piece for The China Project on how the Didi affair should be seen as a regulatory failure rather than as part of a coordinated crackdown, said that “companies in less sensitive sectors such as retail should not have much trouble with a cybersecurity review” before an IPO, although of course there could always be “other regulatory or political factors that would complicate the process.”

But if anyone can take on the challenges of getting funded in the current environment, it’s probably CEO Zhuang Chenchao: When he co-founded Qunar.com in 2005, he took on Baidu, which was then an unassailable monster of a company, and a number of specialized incumbents, for the travel market. Baidu later largely gave up on its own travel search business, and bought a large stake in Qunar, which IPO’d on Nasdaq in 2013.