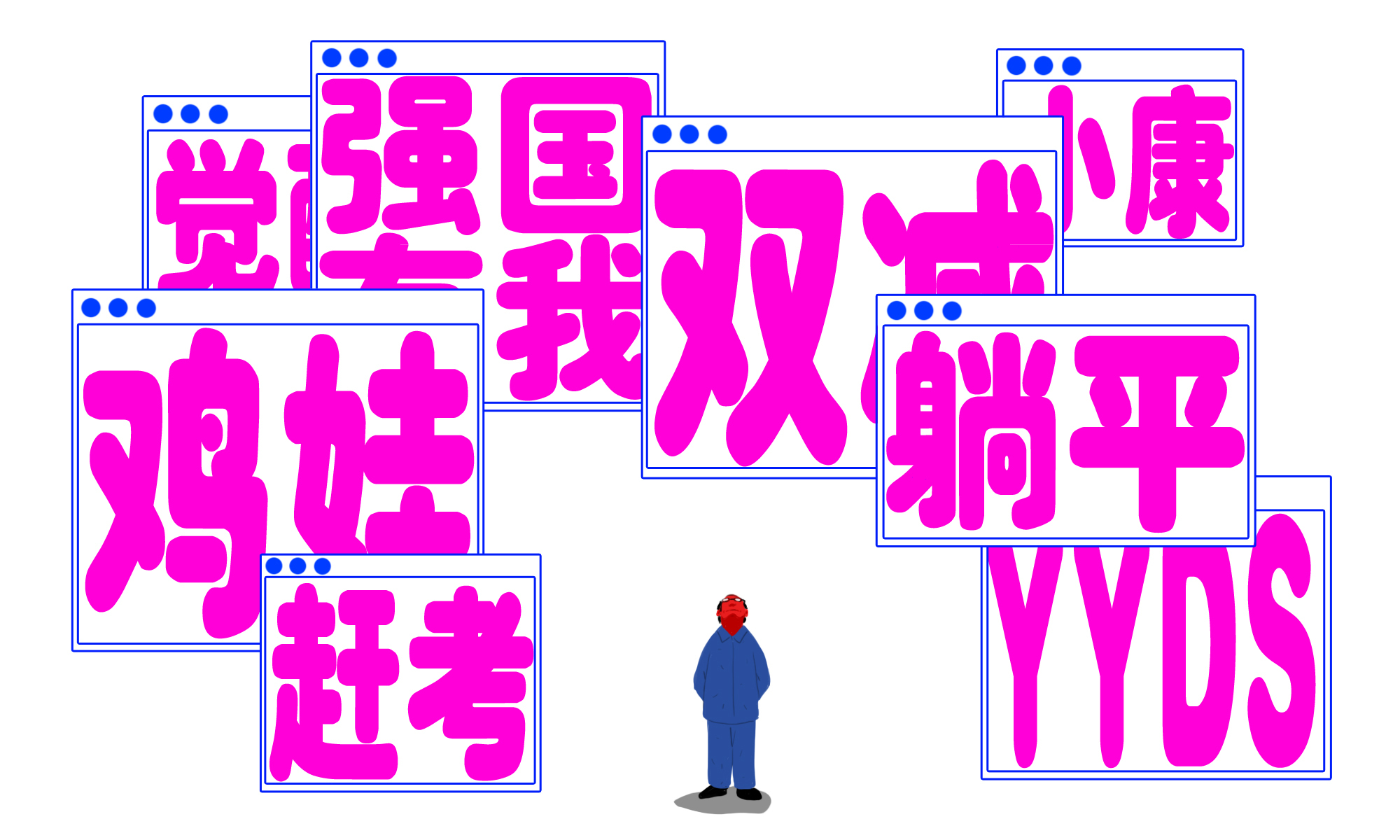

China’s top buzzwords and internet slang of 2021

Two year-end lists of popular slang words and internet catchphrases were published this week. The words offer a glimpse into what’s on the minds of Chinese internet users and Chinese government officials. Here are all 16 words on the lists.

The National Language Resources Monitoring and Research Center at Beijing Language and Culture University yesterday published its annual list of top 10 internet buzzwords of 2021 (2021年度十大网络用语).

“Big data analysis” of over a billion online posts and forum discussions from the Chinese internet in 2021 was reportedly used to decide on the final list, but it’s clear from the selection that the artificial intelligence tool used has a good understanding of socialism with Chinese characteristics.

Separately, the magazine Yǎowén Jiáozì (咬文嚼字) published its year-end list of “popular buzzwords” (2021年十大流行语). Yaowen Jiaozi is a magazine founded in 1995 that publishes stories about the the misuse and abuse of language in Chinese society. Its name is variously translated as “Correct Wording,” “Verbalism,” and “Chewing Words.”

The Yaowen Jiaozi list does not claim to be created by big data, but rather from reader suggestions, online polling, and selection by specialists.

It is a more interesting list.

Below are the words in both lists, with the phrases or words that made it to both lists at the top. Each entry shows which list it’s in: The National Language Resources Monitoring and Research Center is abbreviated to CNLR, and Yaowen Jiaozi to YJ.

Double Reduction Policy

双减 shuāngjiǎn

List: CNLR, YJ

The Double Reduction Policy is the shorthand name for the policy announcement made in July, “Suggestions on further reducing the burden of homework and off-campus training for students in compulsory education.”

It aims to increase the quality of education but reduce the pressures on overworked school kids.

Even though its 30 measures to rein in the education sector were announced nearly six months ago, the Double Reduction Policy was a trending word as recently as this week while its implications continue to play out in China’s education sector.

Lying flat

躺平 tǎngpíng

List: CNLR, YJ

Lying flat, or lying flat-ism (躺平主义 tǎngpíng zhǔyì), first appeared on the Chinese internet in June this year as a reaction of China’s youth to another social phenomenon in China — involution (内卷 nèijuǎn), or intense economic competition for ever scarcer resources.

Nèijuǎn was a top 10 internet buzzword of 2020 and has remained prevalent on social media and in society in 2021.

To lie flat is to choose to escape involution and high-pressure city life, to disengage from the intense social competition of China’s 996 work culture, and to opt for a life of low consumption and little social interaction.

The sting of the implicit social criticism of the word is removed in the National Language Resources Monitoring and Research Center’s buzzword list, which describes tǎngpíng as more of a temporary pause, rather than complete disengagement, an opportunity to gather energy before taking off again.

Tǎngpíng is also in the Yaowen Jiaozi list. Its take on the word is similar — as a way to “recharge and prepare to fight better tomorrow.” But it also adds that tǎngpíng is a way for young Chinese to vent their frustrations at the pressures of life and the high levels of “involuted” competition, and that “lying-flatters” (躺平族 tǎngpíngzú) understand that lying down is no way to win.

Overwhelmed

破防 pòfáng

List: CNLR, YJ

Originally from the gaming world, pòfáng refers to breaking through or tearing down the opponent’s defenses.

The word has evolved to mean being emotionally overwhelmed, a reaction to a piece of bad news that has an impact to the point of someone losing all control of their emotions. Although it is not normally linked to tǎngpíng or nèijuǎn, it can be seen as part of the choice — either take the competition, lie flat, or break down.

Metaverse

元宇宙 yuán yǔzhòu

List: CNLR, YJ

This is the only non-Chinese import in this year’s top 10 list — both in terms of its origin and why it became a buzzword in China this year.

“Metaverse” was first coined in Neal Stephenson’s 1992 science fiction novel, Snow Crash (雪崩 xuěbēng), in which humans interact with each other as avatars and with software.

The word has been a top trending term on Chinese social media, and in entrepreneur and investor circles, since late October, when Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg announced the rebranding of Facebook as Meta.

Profound changes unseen in a century

百年未有之大变局 bǎinián wèiyǒu zhī dàbiànjú

List: YJ

In December 2017, Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 said in a speech: “Looking at the world, we are facing a major change unseen in a century” (放眼世界,我们面对的是百年未有之大变局). He has used the phrase several times since then to emphasize that China faces both unprecedented opportunities and unprecedented challenges.

The sense of an enormous transformation was echoed in an essay that was widely republished by state media in August titled “Everyone can sense that a profound transformation is underway!” (每个人都能感受到,一场深刻的变革正在进行!).

Chicken babies

鸡娃 jī wá

List: YJ

In recent years, the term “chicken baby” (鸡娃 jīwá) has become popular in China, with the increase of obsessive middle-class Chinese parents in megacities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou wanting, and competing fiercely for, the best for their kids.

“Chicken” comes from the colloquial expression dǎjīxiě 打鸡血, which translates literally to “inject chicken blood.” Chicken blood treatment was a fad during the Cultural Revolution, mostly in the countryside. People waited in line, rooster in hand, to receive fresh chicken blood — the cure-all for countless ills, from baldness to infertility to cancer. It was allegedly a great victory for the people, not so much for young roosters. Once the golden age for health gurus passed, the madness over chicken blood subsided — but the phrase survived as an expression to refer to agitation or hyperactivity.

Nowadays, dǎjīxuè is a popular term that can mean giving yourself a pickup, motivating yourself or someone else, or plucking up the courage to do something you’d rather not.

For parents and their kids, injecting chicken’s blood is to muster the courage to take the competitive pressures of schooling in China.

“Kids in the past had extracurriculars as well, but it didn’t serve any purpose except to cultivate hobbies or fun,” said Lansing Jia, a high school teacher in Shanghai. “Today, chicken babies play chess to improve cognitive skills, participate in Math Olympiad for logical reasoning, sports to prevent myopia…Everything has to serve one purpose: to be good at school.”

The above is excerpted from a The China Project article by Han Chang published in June this year: Chicken parenting is China’s helicopter parenting on steroids.

We are ready to build a powerful China

强国有我 qiángguó yǒu wǒ

List: CNLR

“We are ready to build a powerful China” is the second part of a solemn oath taken by the students who attended the celebrations of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) held at Tiananmen Square on July 1 this year.

The full oath is “Please rest assured, we are ready to build a powerful China” (请党放心,强国有我 qǐng dǎng fàngxīn, qiángguó yǒu wǒ), which could be translated literally as “Party, please don’t worry, a strong country has me.”

The phrase is supposed to capture the aspiration, courage, and confidence of the younger generation in the CCP and China’s future.

Wild consumption

野性消费 yěxìng xiāofèi

List: YJ

In July 2021, there was a flood in Henan Province that killed 71 people and displaced hundreds of thousands. A struggling Chinese sports clothing brand, Erke, announced that it would donate 50 million yuan ($7.68 million) worth of supplies for disaster relief.

Yaowen Jiaozi says that internet users “were deeply moved…and poured into the brand’s live broadcast room to place orders to express their support for the caring company. The anchor urged everyone to consume rationally, while internet users shouted, ‘I want wild consumption!’”

Although 野性 yěxìng “refers to an unruly temperament, and ‘wild consumption’ means unconstrained consumption,” Yaowen Jiaozi reassures readers that the phrase is actually good for society because it encourages young people to “do charity without asking for rewards,” and it is also part of a trend of domestic brands becoming popular (国潮 guó cháo).

The opposite of “wild consumption” is “rational consumption” 理性消费 lǐxìng xiāofèi. This phrase was repeated constantly by livestream ecommerce celebrities during the Double 11 shopping festival last month, reminding their fans to shop but not go wild.

The Age of Awakening

觉醒年代 juéxǐng niándài

List: CNLR

The Age of Awakening is a historical drama series and one of this year’s biggest TV hits in China. Produced to accompany the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the drama tells the story of the group of intellectuals based around Peking University that would become key founding members of the Chinese Communist Party.

It is notable for its popular, commercial success, which previous propaganda shows have failed to achieve.

Xiaokang / moderately prosperous

小康 xiǎokāng

List: YJ

Moderately prosperous society, basically prosperous society, or xiaokang society (小康社会 xiǎokāng shèhuì) is an old Chinese term that was introduced back into popular use by Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平 in 1979 as a goal of China’s “Four Modernizations.”

The goal was endorsed by subsequent leaders Jiāng Zémín 江泽民 and Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛.Now under Xí Jìnpíng 习近平, Jiaowen Yaozi notes, at the celebrations for the centenary of the founding of the CCP, Xi solemnly declared that China, under his watch, has built a “xiaokang society in an all-round way.”

A quest to take on the challenges of a generation

赶考 gǎnkǎo

List: YJ

Gǎnkǎo meant to take the examinations to enter the civil service system in Imperial China. (Here, 赶 gǎn means to travel a long distance to take the exam, not to rush to get there, which the character can also mean.)

This system, based on merit (or at least test-taking ability), was how candidates were selected for the state bureaucracy. Starting during the mid-Tang dynasty (618–907), it became dominant during the Song dynasty (960–1279) and lasted until it was abolished in the late Qing dynasty reforms in 1905.

In March 1949, Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 reportedly said: “Today is the day we enter Beijing and take the national examination” (今天是进京赶考的日子) at Xibaipo 西柏坡, a township in Hebei Province, where the Communist Party’s army gathered its forces before the final assault on Beijing in 1949.

In July 2013, Xi Jinping traveled to Xībǎipō 西柏坡, where he recalled Mao’s words, saying that although China had made great strides, and “stood up” in the intervening 60 years, there were still great challenges on the road ahead (赶考之路 gǎnkǎo zhīlù) that were far from over. In his speech for the 100th anniversary of the founding of the CCP on July 1 this year, Xi again spoke of the need to maintain the spirit (赶考之心 gǎnkǎo zhīxīn, or 赶考精神 gǎnkǎo jīngshén) of taking on “tests” facing the next generation.

Peak carbon and carbon neutral

碳达峰,碳中和 tàndáfēng, tànzhōnghé

List: YJ

In September 2020, at the UN General Assembly, Xi Jinping spoke about China’s ambitious targets of hitting peak carbon by 2030, and achieving carbon neutrality before 2060.

Although Beijing’s commitment to achieving carbon neutrality, including in its Belt and Road investments abroad, is sometimes questioned, the Chinese government does not question the science behind climate change, rhetorically at least, and is completely on board to switch moves to cut carbon emissions.

Tàndáfēng and tànzhōnghé, as with any top-down but still quite vague policy framework, have also been trending words among entrepreneurs and investors in China looking for the next big opportunity.

The GOAT (greatest of all time)

YYDS

List: CNLR

YYDS is an acronym for the Chinese phrase “eternal god” (永远的神 yǒngyuǎn de shén). Internet users use it to praise their favorite athletes or celebrities in a way similar to the American slang “GOAT” (Greatest of All Time).

YYDS was a trending word on social media during the Tokyo Olympics this summer, celebrating the wins of Team China, including the country’s first gold won by Yáng Qiàn 杨倩, the three stunning “perfect 10” dives of 14-year-old Quán Hóngchán 全红婵, and the sprinting performance of Sū Bǐngtiān 苏炳添 (a.k.a. “God Su” 苏神 sū shén).

YYDS is not liked by some commentators as it’s seen as not real Chinese.

Confusingly, YYDS can also mean “forever single” (永远单身 yǒngyuǎn dānshēn) in internet slang, so context is important!

Abso absolutely

绝绝子 juéjuézi

List: CNLR

The neologism 绝绝子 juéjuézi became a popular trending comment during the Chinese boy band talent show CHUANG 2021 (创造营2021 chuàngzào yíng èr líng èr yī), which aired in China between February and April this year.

Produced by Tencent, the reality show pitted 90 male contestants from China and other countries against each other, with the 11 finalists forming the boy band group INTO1.

The word can be used to express admiration and awe, but it can also be used to mean that something is unbelievably awful, depending on the context.

It doesn’t hurt, but it’s really embarrassing

伤害性不高,侮辱性极强 shānghài xìng bù gāo, wǔrǔ xìng jí qiáng

List: CNLR

“Not that harmful but extremely embarrassing” started life early in 2021 as a comment on a Douyin clip of two men and one woman eating a hot pot together. The comment described the woman, sitting in the middle, who appears to be left out as the other two affectionately pass food to each other with their chopsticks.

The phrase has come to mean a situation that appears benign at first but is actually really bad.

I didn’t get it, but I was in awe

我看不懂,但我大受震撼 wǒ kàn bùdǒng, dàn wǒ dàshòu zhènhàn

List: CNLR

“I didn’t get it, but I was in awe” is how Taiwanese-American film director Ang Lee (李安 Lǐ Ān) described his reaction when watching the 1960 movie The Virgin Spring in an interview for a 2013 documentary about its director, Ingmar Bergman.

In the documentary Trespassing Bergman, a group of filmmakers, including Ang, visit Bergman’s house on the remote Swedish island of Faro to discuss his legacy.

The phrase has crossed over into mainstream use in China, describing confusion, shock, or being totally lost.