For years, China's small but dedicated Ultimate Frisbee community has been trying to grow the sport in incremental fashion. Last year, quite suddenly, Ultimate exploded in popularity — but for reasons no one could have predicted, with results that not everyone likes.

Broken forces, uncalled rule violations, listless cuts, dropped passes: it’s Ultimate Frisbee night in Beijing’s Dongfeng Park, and the field is total chaos. After a casual warmup of trick throws — rarely used in competition — the six-a-side game begins on a small field. A point drags on until one team finally scores, and the teams line up to do it again. No one seems to mind that people out here aren’t any good.

Competition isn’t the point — not when you’re taking part in one of China’s newest fads.

Ultimate Frisbee — which in Chinese has been given the literal translation of jíxiàn fēipán 极限飞盘 — was introduced to China by American expats in the late-’90s / early-2000s, but only in the past year has the sport’s popularity exploded — thanks to influencers selling a lifestyle, many of them on an app called Little Red Book (小红书 xiǎohóngshū).

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

When he first started playing in 2006, Zhāng Kūn 张坤, a veteran in the Beijing Ultimate scene, said there were fewer than 100 Ultimate players in Beijing, and most were expats. Despite high points in the sport’s development — “Ultimate Frisbee’s Hippie-Go-Lucky Culture Hooks Chinese Youth,” reads the headline in a 2015 Huffington Post article — Ultimate remained niche. Zhang helped organize national and international tournaments along with weekly pickup games in Beijing, seeing only a modest uptick in players over the years as expats came and went.

Then last October, he noticed what he calls an “explosion” of interest. Where there would normally be a few dozen people at pickup, suddenly there were 100. Additional games sprouted in far-flung parts of the city.

“Many years ago, when I played Frisbee, people thought it was strange,” Zhang said. “Last year, it attracted some attention. This year, if you don’t play Frisbee, you’re the one that’s a little strange.”

Zhang attributes the sudden popularity of the sport to two things. In the early days of the pandemic, “influencers found Ultimate Frisbee, and they thought it was cool. Very cool.” And then Little Red Book, an app that’s “kind of like Instagram, Etsy, and Amazon all in one,” according to one digital marketer, leaned into the sport’s popularity and began to highlight those influencers.

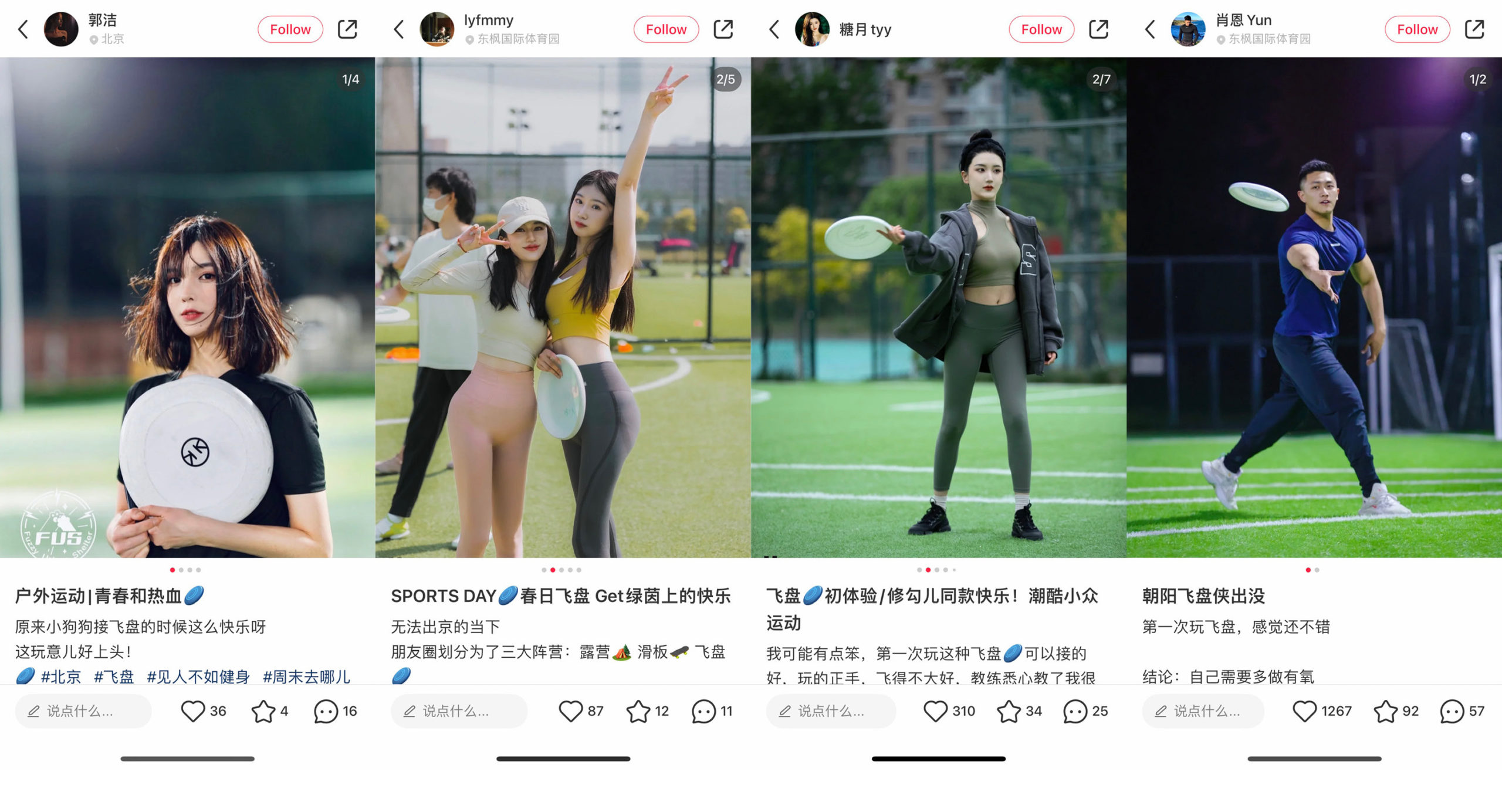

Interest skyrocketed from there. According to Little Red Book, searches related to flying discs grew by six times from 2020 to 2021, and 17 times from 2021 to 2022. The topic has attracted more than 42.4 million views on the platform. “People are actively searching for Frisbee, and they’re searching for things like, ‘What should I wear when I play Frisbee’ or ‘Where should I go to play Frisbee?’ or ‘What kind of shoes?’” according to a company representative. In some cases, users can buy that apparel directly from the app.

Dǒng Dá 董达, a.k.a., KUBA, a photographer who has promoted Frisbee in Shanghai since 2014, noticed brands and advertising companies getting involved in early 2021. He’s been trying to expose big-name brands to competitive Ultimate since; recently he organized a show match for Puma, the sportswear manufacturer. “I hope that in the future, brands can contribute to the competitive aspect of Ultimate,” he said.

Jessie Yu, who has played Ultimate for nine years and is a driving force behind a women’s team in Shanghai called the Sirens, pinpointed sponsorships as a potential benefit. “The fact is, many sports companies like Nike, Adidas, Puma, Li Ning have all started paying attention to Frisbee,” she said. (Ultimate was also recently featured in an ad during Tencent’s broadcast of the NBA conference finals.)

But she is also concerned that “fashion Frisbee” will give Ultimate a bad rap. “Lots of people think more exposure means bigger opportunities to expand the community, which consequently leads to better chances of getting more good players,” she said. “I can’t say they’re definitely wrong. But from what I’ve observed here in Shanghai, all these rapidly expanding ‘social Frisbee’ groups are detrimental to the [image of] competitive Ultimate as a real sport.”

Zhang Kun is philosophical about what this all means. “I don’t hate this. It’s not bad. Most new players really think Frisbee is cool, it’s fun. I think that’s cool because more people will play, and the sport will be more popular.

“I don’t really care about Little Red Book, but during this period, I learned something about the logic [behind the app]. Because if you want to become more popular, or you want people to come to you, you have to publish on Little Red Book, or you have to have good-looking people.”

Ultimate’s journey from the U.S. to China

Ultimate was invented in the late 1960s in a New Jersey parking lot. In its early years it was considered a “hippie” sport, a countercultural rejoinder to traditional American sports like football. The game’s cornerstone is an element called “Spirit of the Game,” which encourages players to resolve conflicts amongst themselves, without a referee.

From New Jersey, Ultimate spread throughout the U.S., eventually spawning grassroots leagues and tournaments around the world. The World Flying Disc Federation (WFDF) was founded in Colorado in 1985 and hosts high-profile biennial world competitions, which has seen Chinese participation over the last decade-plus.

In North America, the game is trending away from its counter-cultural roots. The American Ultimate Disc League (AUDL) was founded in 2010 in a bid to professionalize the sport. That meant the introduction of referees and new rules that encourage pace of play. (A rival organization, Major League Ultimate, played games from 2013 to 2016.) AUDL has made some inroads. Game highlights have made it onto ESPN, and there’s hope that by 2028, a version of Ultimate will be played at the Olympics.

In China, Ultimate was first established, separately, in Beijing and Shanghai; a rivalry formed between the cities’ respective top teams — Big Brother in Beijing, Huwa in Shanghai — and players from these clubs helped spur local development. A few companies have invested in the game’s growth, most notably Yikun, which produces a 175-gram disc that is WFDF-approved for tournament play and often sponsors competitions. But in the last three years, COVID has halted the competitive scene; where once there were more than a dozen tournaments every year — including China Nationals for colleges — competitive games these days are now largely limited to intercity scrimmages.

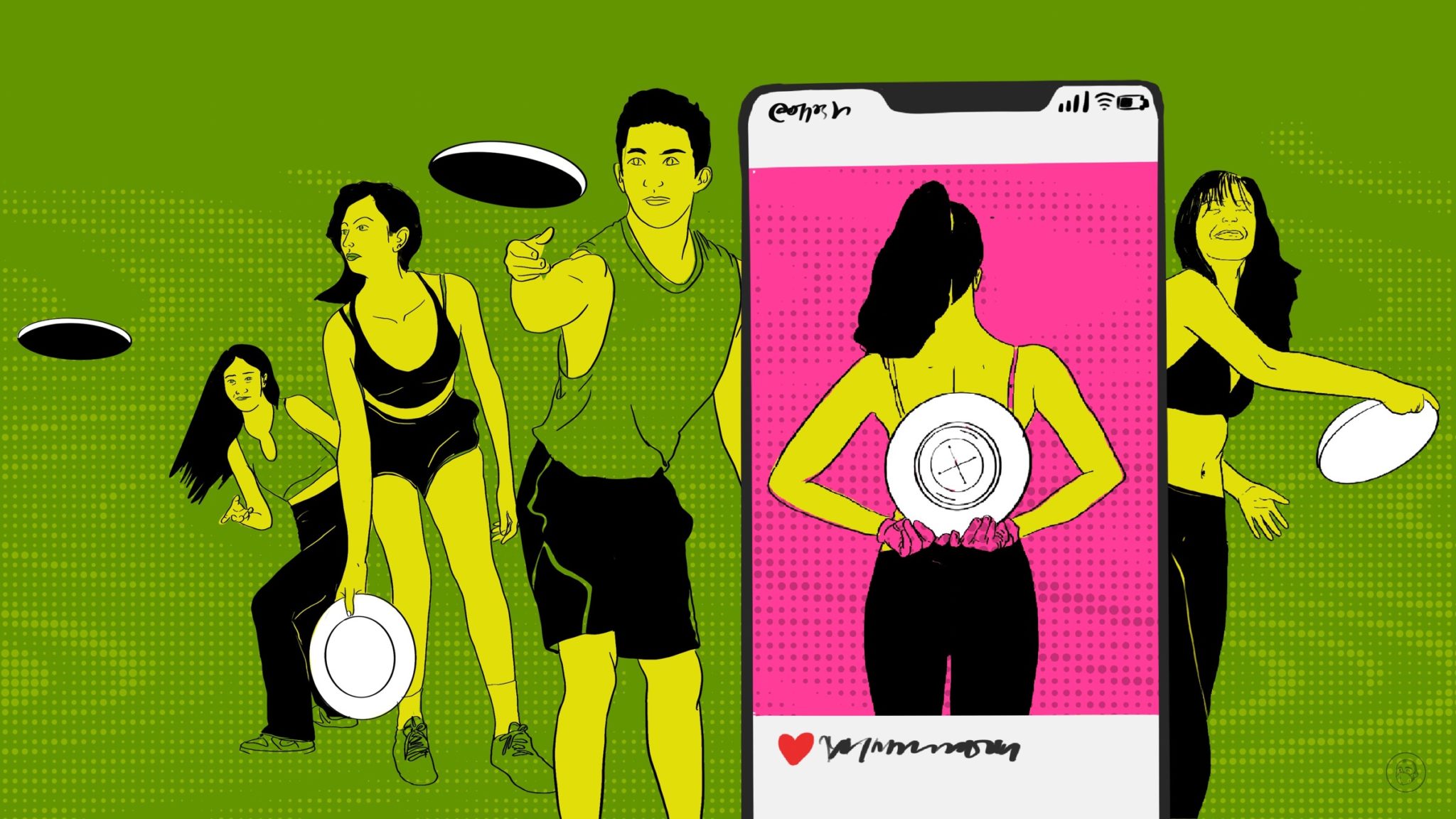

Ironically, it was during this time that Ultimate really took off. The sport has surged to the mainstream because it is seen as fashionable. Search for “Frisbee” and you’ll find thousands of oddly similar posts of influencers in tight, branded athletic gear posing with discs. Playing the sport seems incidental to projecting a very specific aesthetic.

These influencers have done what true believers weren’t able to through decades of diligent, grassroots promotion: They’ve made the sport look sexy.

“We’ve been [promoting the sport] for many years and all of a sudden it became so big and popular, and of course we find it really intriguing,” said Marshall Wang (汪若阳 Wāng Ruòyáng), who began playing as a teenager in 2008 and gradually worked his way up to becoming one of the captains of Big Brother. “We do feel like it’s a little bit bizarre. But at the same time, we have always envisioned this Ultimate thing becoming really popular.”

Wáng Bīn 王彬, a player and coach who runs summer leagues in Beijing, bristles at these recent developments, and is eager to differentiate Ultimate as sport from Ultimate as fashion.

“It really is quite strange,” he said. “I’ve played Ultimate for 15 years, I know this is not what Ultimate looks like. But my own Ultimate community isn’t like this. We focus on the competition itself, and most of our events don’t even offer photo ops.

“I personally think that Frisbee was able to become so popular because Ultimate the sport is so fun to play. Little Red Book has exposed more young people to the sport, that’s all.”

The fashion sport

Earlier this month, a friend convinced Lù Guìtíng 陆桂婷, a 24-year-old commercial lawyer from Beijing, to give Ultimate a shot. Lu had seen photos of players on social media, and she was curious. “I could tell from those pictures that people were enjoying this game. I thought, maybe that’s good exercise, maybe I should try. So I went to Chaoyang Park and I joined the game.” It was love at first flick.

Alex Wang (王磊 Wáng Lěi), a programmer and community organizer, has seen Little Red Book’s impact firsthand. When he started playing Ultimate in 2015, “Only a few people tried it, and even fewer people continued to play it,” he said. He launched a new team called PET Fly 2.0 last summer, and membership ballooned. “It happened so, so suddenly. It’s really beyond my expectations.”

At Dongfeng Park, he points to the next field over, where a team of beginners dressed in brand-name labels is learning to throw the backhand, the simplest throw in Ultimate.

“They’ve hired a professional photographer,” he said. Many of the photos will be bound for social media, most likely Little Red Book. “For new players, good pictures are important. They can share them. It’s a kind of signal to their friend circles that ‘I’m a fashionable guy, I join fashion sports.’”

Wang recently decided to hire a photographer to his team’s games, too. “I have to,” he said. Otherwise, another team that offers photography will poach his players, who pay between 40 and 100 yuan ($6 to $15) for every pickup session or practice.

“The pickup level is pretty low,” said Zoey Tang (汤桢莹 Tāng Zhēnyíng), a Big Brother co-captain. She spends lots of time helping up-and-comers learn the game, but notes, “You cannot expect normal Frisbee to be played. So you have to slow down. Otherwise it’s really easy to get injured.”

“I think a lot of those people have probably never played sports before,” Tang said. “Never, ever. I’ll give you an example. I have to teach them how to run. Like, what’s running? What’s cutting? I have to break down each step.”

The question remains: Will Ultimate, like other fads, be short-lived? Or might its social media popularity lead participants to further dabble in an athletic lifestyle?

Alex Wang of PET Fly 2.0 thinks the sport may be in China to stay. “I think it will grow more popular at least within the next one or two years,” he said. “I think Frisbee has this potential, compared to other sports, because of its unique features. It’s good for socializing, it’s intense, and it’s fun and interesting to play.”

Wang Bin believes the fashion aspect of the sport will fade, but Ultimate in China may have another explosive growth spurt yet — if it is ever added to the Olympic Games. That would garner the full attention of China’s national sports bureau. Wang’s hope — one repeated by several players — is to see Ultimate at Los Angeles 2028. “Ultimate in the future may not be a sport that’s fashionable,” he said, “but it will become a sport that is beloved.”