Below is a complete transcript of the live Sinica Podcast with Jude Blanchette and Ryan Hass.

Kaiser Kuo: Welcome to the Sinica Podcast, a weekly discussion of current affairs in China, produced in partnership with The China Project. Subscribe to Access from The China Project to get Access. Access to, not only our great daily newsletter, but all the original writing on our website at thechinaproject.com. We’ve got reported stories, essays and editorials, great explainers and trackers, regular columns, and of course, a growing library of podcasts. We cover everything from China’s fraught foreign relations to its ingenious entrepreneurs, from the ongoing repression of Uyghurs and other Muslim peoples in China’s Xinjiang region, to Beijing’s ambitious plans to shift the Chinese economy onto a post-carbon footing. It’s a feast of business, political, and cultural news about a nation that is reshaping the world. We cover China with neither fear nor favor.

I’m Kaiser Kuo, coming to you today from Oakland, California.

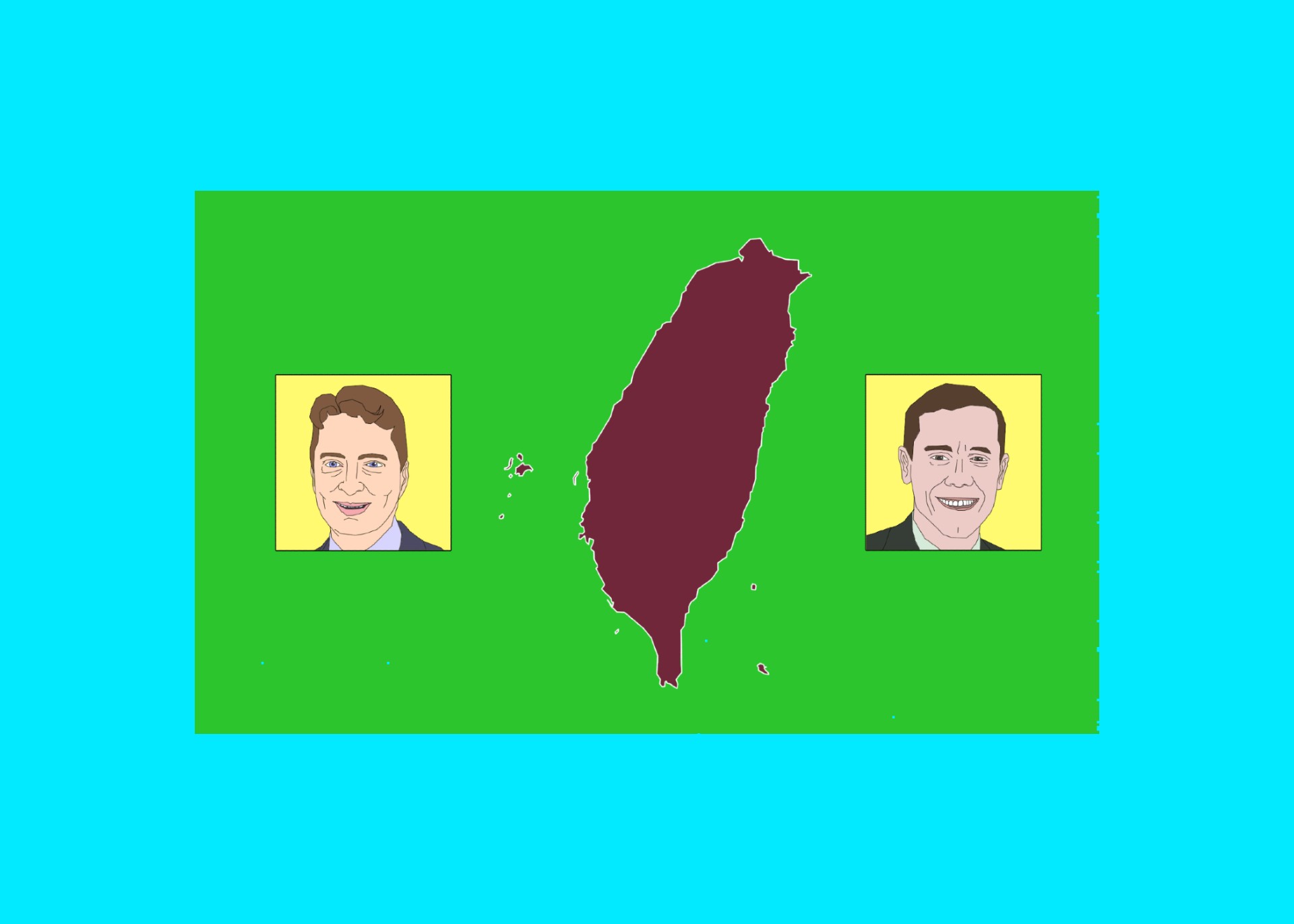

Before I get started, I want to let you know why we didn’t have a show the week of December 12. My mother passed away on Tuesday the 13th, and I flew out Monday in time to say goodbye. The connection to China that I feel, my understanding of China really owes a ton to her. And so, I dedicate this show to the memory of Mary Kuo, Liu Tan-lee 刘诞丽. I think she would’ve been really, really happy to read this essay — I actually read part of it to her while she was still conscious — that’s going to be the topic of today’s discussion, and to meet its co-authors, both of whom I’ve had on the show multiple times in the past, and who are doubtless known to the listeners. The essay that we’re talking about today is in the forthcoming issue of Foreign Affairs and is available now online. It’s called “The Taiwan Long Game: Why the Best Solution is No Solution.”

It argues, I think very persuasively that, quoting here, “Sometimes the best policy is to avoid bringing intractable challenges to a head and kick the can down the road instead.” Don’t know if the rhyme was deliberate, but it’s a good way of putting it. The essay’s authors are Jude Blanchette and Ryan Hass — Gentleman I greatly esteem and who’s teaming up on this essay and in a joint podcast called Vying for Talent, delights me. Jude Blanchette is Freeman Chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, CSIS, and is the author of China’s New Red Guards: The Return of Radicalism and the Rebirth of Mao Zedong.

Jude, great to see you, man.

Jude Blanchette: Thanks, Kaiser. It’s a real pleasure to be here.

Kaiser: And Ryan Hass is Armacost Chair at the John L. Thornton Center at the Brookings Institute, Senior Advisor at the Scowcroft Group, and Senior Advisor at McLarty Associates. Ryan was a foreign service officer who became the China director at the National Security Council during the second Obama administration. He’s the author of the excellent book, Stronger: Adapting America’s China Strategy in an Age of Competitive Interdependence. We featured him as a keynote speaker at our Next China Conference, and I’ve interviewed him about that book and many other things. Welcome back, Ryan. Great to see you again.

Ryan Hass: Thanks for the opportunity, Kaiser.

Kaiser: So, the opening paragraphs of this essay, I think, seem to make clear the motivation that you had in writing it. You described this growing chorus in the Pentagon and on the Hill. People who seem to believe that a Chinese invasion of Taiwan will happen sooner rather than later, and urging preparation for a war with China. This is something that I talked about recently with Mike Mazarr, and thanks, by the way, Jude, for making that introduction. But this approach, as you say, supposes the U.S. to be confronting a military problem with a military solution, whereas you believe, instead, that what we face is a strategic problem with a defense component. That distinction might be a little tricky and not obvious to everyone listening, or even reading the piece. So, maybe we can unpack that a bit, explain what it is that we mean when you say that we have a strategic problem with a military component rather than a military problem with a military solution.

Jude: Sure. Yeah, that’s a important question that, for Ryan and I, gets to the heart of this conundrum, which is increasingly, I think certainly over the last year and a half, the discussion in D.C., but in policymaking circles in other parts around the world, has really started to narrow down what many think the problem is. I think this especially exacerbated after Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, which seemed to telescope straight to the Taiwan Straits. And so, I think the theory of the case is you have similarities between what Vladimir Putin did to Ukraine with how Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 is talking about Taiwan. You have an increasingly powerful military in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) under the leadership of the Communist Party, which has for a very long time denied the independence of Taiwan and have made threats to using military force to ultimately compel Taiwan to come to a political solution with Beijing.

And so, I think, to some extent, reasonably many are saying, well, we’ve got to find a way to deter that action. I think I grant that; I don’t know if Ryan does, but I think our argument is that that’s about 4% of the issue if you look at this more holistically. And that fundamentally, the challenge that the people of Taiwan and the United States face instead, I think, is a much broader diplomatic, economic political challenge — one that certainly has a military component, but if we’re just looking at this through a narrow military lens, we’re missing the heart of the challenge. I think most consequentially, we’re going to inevitably make this a military issue where that’s the exact thing that we want to avoid.

Kaiser: No, that’s great. That really helps to make that much more clear. Obviously, your essay wins my approbation, as somebody who is always banging on about the need for more cognitive empathy, when you write that “to preserve peace, the United States must understand what drives Chinese anxiety.” And then you go on to say, “and ensure that Chinese President Xi Jinping isn’t backed into a corner and convince Beijing that unification belongs to a distant future.”

But that exact same passage, I think, is surely going to raise hackles, I think, the moment certain eyes take in those words. A lot of people are going to draw immediate parallels, as you say, to Putin and Ukraine, and to use those arguments to try and pin you. Isn’t this the same as those people all insisting that we take Putin’s concerns over NATO expansion and Russian national security seriously? Wouldn’t the policy you’re advocating simply amount to capitulation to PRC’s threat of force? Ryan, how would you respond to that criticism? I should note, though, that you do anticipate this line of attack and address it a bit in the Foreign Affairs piece. But I’m just curious, just at the top here, to maybe head off that line of attack.

Ryan: Well, Kaiser, let’s just establish at the outset that neither Jude nor I are trying to argue that China is anything other than bloody-minded in its determination to try to compel unification with Taiwan. China is absolutely determined to do so. I think part of the argument that we’re trying to advance is that military options may not be the option of first resort in China’s efforts. What we’ve already seen is that China is engaged in a strategy of coercion without violence. This isn’t a future hypothetical. This is an everyday reality today, where China is using an abundance of tools to try to wear down the psychological confidence of the people of Taiwan; that resistance is futile; that there is no path to peace in prosperity that does not run through Beijing, and that the people of Taiwan’s best hope is to sue for peace now rather than invite pain later.

That’s what the people of Taiwan are facing. And if we become target locked on some future hypothetical invasion scenario and begin to treat it as an inescapable inevitability, we could find ourselves sort of driving down a path that may not be necessary. And beyond that, we are not addressing the problem that the people of Taiwan are feeling today. And so, part of, I think what Jude and I are trying to do is to try to encourage a bit of a mindset shift in Washington to understand that yes, there is a real risk of future conflict. It’s not an inevitability but it is a real risk that must be taken seriously. But even as we take that risk seriously, we have to also contend with the everyday realities that the people of Taiwan confront today.

And unless we sort of rise to that challenge, then our own interest will be disadvantaged. Because ultimately, what we are talking about in this piece is how to protect America’s interest. And what are America’s topmost interests? It’s preserving peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait. And in order for us to sort of adhere to that North Star, we have to have a clear understanding of the nature of the challenge that we and the people of Taiwan confront.

Jude: I also want to add that it is an inescapable reality that you will have to wrestle with what China is thinking about this. No matter how you come down on this issue, whether you’re far more to the hawkish spectrum than I am, you still are going to have to try to wrestle with how Beijing is conceptualizing this. As best we can, try to think through the decision-making calculus that Xi Jinping is utilizing. And indeed, one of the most frustrating aspects of this discussion and debate is I notice there are those who say, occasionally, we just need to listen to what Xi Jinping says, right? And they’ll pull out a passage from a given translation of a Xi Jinping speech that lays out what they think is a very expansionist view of Chinese interests and intentions.

That’s fine. I think showing your math is good. I think we’re all engaged in the game of trying to understand what Chinese calculus is. I just would argue that we have to bring as much available data and input we can to making determinations about what China thinks. And the final thing is we ended up getting to this place with the Soviets in the Cold War, right? And in fact, this was one of the most critical, most important tools we had is an attempt, in a nuanced way, to understand what the Soviets were thinking. That doesn’t mean you countenance their actions; doesn’t mean you agree with what they’re trying to do. It’s just understood to be a necessary tool in the toolkit to achieve your interests and avoid unnecessary conflict.

Kaiser: Yeah. I mean, that’s the thing that’s frustrating to me when I try to sell this idea of cognitive empathy. They seem to be unable to differentiate that from just plain old sympathy, which is just absurd.

Ryan: One of the things that we often hear is that China is investing so much in its military capabilities, and therefore that tells us that China is preparing for a future conflict with Taiwan. I understand the logic of it. I just think that it breaks down under interrogation. The World Bank estimate of China’s military spending is that they spend around 1.7% of their GDP on defense; somewhere in the ballpark of $200 billion. Now, they probably spend more than they report. So, let’s just say they spend 1.8%, 1.9%. If they were in NATO, that would be below the 2% minimum threshold of defense spending. They are a rising power. Rising powers spend money on their national defense. China does have the largest surface navy; it does have the largest standing army; it does have the largest missile force.

So, we don’t take any of these threats lightly. But they also have their own limitations. They have one overseas military base relative to 800 of ours around the world. They have territorial disputes with five of their neighbors. Four of their neighbors have nuclear warheads. None of them want to be subordinate to China. And so, I think that taking a broader picture helps sort of put into context a little bit of the texture of what Jude and I are trying to put forward.

Kaiser: Right. That military aggrandizement does not translate directly into an intention to attack Taiwan. The expansion of the PRC’s military capabilities is one of the three factors that you cite; that you say really changed the situation after three decades of relative stability. What you describe, and I think I would agree, is there’s been a successful policy, though. The second factor that you cite, I think, is also mostly uncontroversial that China, under Xi Jinping, has gotten more assertive, including over Taiwan. I mean, some might quibble, but let’s set that aside for now and look at it more closely in just a bit. But this third factor is bound to generate some controversy. You write, I’m going to quote here, “The United States has abandoned any pretense of acting as a principled arbiter committed to preserving the status quo and allowing the two sides to come to their own peaceful settlement.”

Let’s talk about that, and maybe we can begin with this idea that there was a status quo to begin with — one worth preserving. I see eyes roll in some quarters whenever somebody suggests that there even was a status quo to begin with, which I find to be baffling, but it appears now to be an assertion that we have to defend. So, what was this status quo that you were referring to?

Jude: That’s a great question. If I may answer it in a somewhat roundabout way, by first getting to an offhand comment you just made, which is success in existing policy. I think a threshold, or for me at least, a foundation, has to be understanding that imperfect as it was, the approach of the United States in managing this very vexing problem since normalization, through relatively recently, has been, I think, on almost every metric, successful, if what you’re choosing for success is the United States, as Ryan said earlier, maintains broadly peace and stability in the region, and I think crucially, that Taiwan is given the space to grow as a prosperous, resilient liberal democracy, which it is on almost every measure.

Kaiser: Inarguably.

Jude: Let’s just start with that, that people have been kvetching about the limitations of strategic ambiguity since the Roman Empire without, I think, recognizing how fundamentally successful it has been, again, in an imperfect way, but when measured against alternatives in maintaining that status quo. Now, get to your second point, which is, is status quo the right word to use? That’s not the hill I would die on for that specific two magic incantations. What I would say we’re thinking about when we say status quo is not a technical sense of freezing in motion events across the Taiwan Strait, which has never been the case. It has always been true that U.S. one-China policy has been adaptive because there’s no sort of fixed set of actors, and there’s no, sort of, this is a constantly churning, moving, very complicated relationship that involves dynamics within China, dynamics between China and Taiwan, dynamics within Taiwan, dynamics between Taiwan and China.

And, of course, add us into the mix. I can’t do the math on how many different relationships that is, but it’s a whole complicated set of relationships that the United States, for its own part, has been consistently trying to manage to keep that imperfect balance in place to where China does not invade, Taiwan is given the space to grow, and the United States interests are protected in the region. So, you want to call it an equilibrium? Call it what you will. I think that’s what we mean when we say something like a status quo.

Kaiser: I mentioned just now that you talked about this sort of third factor, the abandonment of the pretense of being a principled arbiter. I imagine that most people who defend current American policy would simply point to the second factor that you cite that China has gotten a whole lot more aggressive, and say that this has been a sensible response to an uptick in Chinese aggression. And to address this, I suppose we need to examine, to what extent… I said we would do this earlier, and now we have to. China really has gotten more bellicose when it comes to Taiwan. You guys answered this in part by examining why Beijing hasn’t already used force, which I think is a really sensible approach, but I also think that it’s important here to rightsize what China has actually said and done.

As Jude said, we need to look at the sort of totality of the statements and the actions. And I know, Jude, you’ve done pretty close reads of not only the white paper that came out shortly after Pelosi’s visit, but also of what some people were calling the work report. The report at the 20th Party Congress. And so, maybe staying with you for a second here, can we look at this question of how much change really has there been in China’s posture, and then maybe look at the reasons you cite as to why, maybe we can turn to Ryan for that, why China hasn’t used forest, even if it does enjoy a military advantage, arguably?

Jude: Yeah, that’s a really important question, in part because some of the documents you referenced, the white paper that came out in August, the last one came out 20 years prior. We have things like last year’s history resolution. The last one was 1981. We have the report that was issued at the 20th Party Congress. We have Xi Jinping’s speech marking the 100th anniversary of the Communist Party, in addition to other speeches that Xi Jinping has made or documents issued. So, we have a set of the most authoritative statements that have come out of the Communist Party and come from Xi Jinping personally. And I think that’s the body of text that we’re working with when we’re trying to understand at least what China says. I should just mention that I think some folks will, depending on how they’re coming down at this, dismiss these statements as mere politicking.

I get that, and some part of me agrees that when we look at statements that come out of any political entity, we need to understand that there are multiple audiences and multiple usages of those statements. But what I would say is, especially things like the Party Congress report, the history resolution, these are not designed for you. These are designed as messaging for the Party state system to understand how the Party views an issue, what the priorities are, and to give some degree of predictability about here’s how we’re thinking about the issue. So, what have they said on this? Xi Jinping has been broadly very consistent to say that China’s preferred path to achieving reunification, in their words, is to use peaceful means. Now, we need to caveat that by China’s view of peaceful means, just means non-military means. But it certainly includes economic coercion, political warfare, election interference; the exercises they did in response to Speaker Pelosi’s trip, which is a part of China’s sort of psychological warfare to try to bend and break the will of the Taiwan people.

So, this is not purely benign, but if we’re just thinking about how are they… Have they run out of patience? And are they now going to start thinking about the previous unthinkable direct attacks, invasions? China’s statements in all of its authoritative documents are saying, we think time and momentum is on our side. It’s a historic inevitability that we will get to reunification. And we’re going to try to use peaceful means. Again, appropriately contextualize that their peaceful does not mean benign. What we would be looking for, if we’re looking for Xi Jinping starting to say, “time is not on my side,” these are small tweaks in the statements, but they would be very important. Consistently not referencing peaceful reunification. Instead of saying that secessionist elements on Taiwan remain a small minority, if we start to see them frame that the secessionist or bad elements on the island are now sort of a majority.

So, we would be looking for these shifts in verbiage that are more clear signals that Xi Jinping sees the runway is ending, and that we would expect him to start taking more drastic actions.

Kaiser: And we’ve simply not seen these.

Jude: No. And just final, again, I think Ryan and I continually try to anticipate counter-arguments on this. But I would say it’s also, we shouldn’t just look at what Xi Jinping says on Taiwan. This is a holistic view you have to bring to this of statements plus actions, plus military preparations. There’s a whole complicated equation here, but an important element of this would be Xi Jinping’s words. And then final thought is what some have pointed to, which is statements Xi Jinping has made about we can’t pass this issue on from generation to generation, or that we need to achieve complete reunification by 2049. I would say two things. Number one, those are very, in the first case of not passing this down generation to generation, Xi Jinping first said that in 2013, again in 2019; that’s not a very specific statement. If I’m reading that as political language, I’m hearing him say, “We’ve been snowplowing this ahead for a very long time. We got to get serious about… We can’t just kick the can in perpetuity.”

Second one is, look, if any CEO came up and said they had a goal that they would achieve by 2049, you would know that that’s pure stall for time. It’s not a serious timeline.

Kaiser: Right.

Jude: It is a way, I think, for Xi Jinping to both signal conviction and seriousness without boxing himself in on too narrow of a timeline. As Ryan and I say in the piece, it’s illogical, it’s not very Xi Jinping like, and it’s not very strategic to give yourself a fixed firm deadline, which then removes your options. And I think it’s clear that Xi Jinping is trying to have his cake and eat it too, by saying, “Look, I’m very serious about this, but we might potentially need 30 years to realize this.”

Kaiser: Okay. You said that we would turn to Ryan and talk about why, despite China enjoying, again, arguably a military advantage, why it hasn’t gone kinetic.

Ryan: Sure. Well, I will take a swing at that, but I also want to just pile onto what Jude was saying, because another theme that comes up in these conversations sometimes is reports that President Xi has instructed the PLA to be ready by 2027 to use force against Taiwan. I just want to make sure that we put that in proper context as well because this is not new or original. It’s pretty common for Chinese leaders to instruct their forces to be ready for future contingencies. Taiwan has been the PLA’s top security priority for decades. So, this is not new. But it’s also important to note that it reflects an in mission that the PLA is not ready today if they have until 2027 to get themselves ready. I think that that’s important to keep in context as well because this often gets woven into discussions about signals of inevitability of future conflict.

On your question, Kaiser, about why the Chinese have not used force yet, even though they could have, I think it reflects the fact that the Chinese understand that they face indivisible vulnerabilities. They require imports of oil; they require imports of food to feed their people; they require imports of semiconductors and other advanced machinery in order to advance their economy. They also, I think, recognize that if there ever was a need for conflict, it would be a pretty Pyrrhic victory — Taiwan’s economy would be in tatters; their export driven economy would be crushed; their goals of national rejuvenation would be set back dramatically. Whoever survived in Taiwan would be violently opposed to being occupied. And they would probably find themselves in direct conflict with the United States, Japan, and possibly others.

And so, I think where this leaves the Chinese is that they’re clearly investing significantly to purchase the future option of use of force, but it isn’t their tool of first resort. I think that they would use force if they felt like they could do so on the cheap. In other words, if they would face no resistance from us, or minimal resistance from Taiwan, or if they felt like they were backed in the corner and had no other alternative or recourse, and that even though they may suffer catastrophic damage, that this was something that absolutely had to be done.

Kaiser: A lot of things come to mind from your response just now. One I should point out that actually Jude, you and Gerard DiPippo actually authored a CSIS report that looks at the likely costs of military intervention, and argues, and I think that you and Ryan use the same phrase, or Ryan just did, they call it a Pyrrhic victory? “Any victory” would be, at best, Pyrrhic. I’ll link to that report on the podcast page and in the transcript. There’s something else that came up earlier. We talked about time; whether time is on Xi Jinping’s side. Again, I mean, I was interested to see that in the report he actually used the phrase “… is always on our side.” But in fact, I think they recognize increasingly that time is not on their side.

I mean, look, they are not blind to Taiwanese public opinion; this growing Taiwanese identity quite, not just separate from, but opposed to a Chinese identity. A broad rejection of the one country, two systems formulation, especially after the imposition of the National Security Law in Hong Kong. Just mounting frustration over the way that Taiwan has been excluded from and marginalized in these international organizations — the World Health Organization — in the beginning stages of a global pandemic. I mean all of this. Anyway, you write something to the effect that when it comes to the appeal of one country, two systems in Taiwan, the Communist Party is pretty clear that there’s no appeal at all. It’s zilch. They’ve said publicly that “time is on our side”, as we’ve still talked about, but they know that it’s not. And nor is it a belief in Taiwan or in Washington. What are the implications of this, though, if nobody thinks that time is on our side, doesn’t that seem like you could cobble together an argument that some kind of action is inevitable? Well, how would you respond to that?

Jude: I think this gets to the heart of the argument we’re making, or at least the proximate cause for it, is looking around at the discussion in D.C., looking at the discussion, the informal discussion, discussion we’re having on track IIs and looking at Beijing’s recent actions. And then looking at the discussion in Taipei. The heart of it is you now have all three primary actors who feel a sense of urgency, who feel a sense that time is not on their side, and what we need to find a way to do is to get this back in a position where folks are thinking about this as a longer-term challenge to manage rather than, as you say, some rapidly boiling pot, which is about to sort of spill over.

I think all three actors have their own specific reasons for why they’re feeling the sense of urgency. I think there is a share of blame to go around in a narrow political sense. Although, we start out, or we say somewhere in the piece that, ultimately, as Ryan said at the outset of this conversation, I think Beijing is the bad actor here. Fundamentally, it’s the one that is looking to annex a peaceful democracy. But I just think that gets you to the two-yard line. I think a sense that we’re in the moral right, which we are, I just don’t think gets us that far because then you’re left to try to manage this profound, profound challenge. I think Beijing, as you say, although the official documents are saying time and momentum are on our side, that’s a political statement.

It’s also a statement that is saying Xi Jinping’s not itching to take catastrophic kinetic action. But if you look more carefully at China’s actions, it’s clear, as you say, they’re looking at growing an increasingly close relationship between the United States and Taiwan, especially on the security and defense front. They’re looking at growing security architecture and discussions in the Indo-Pacific involving Japan, involving Australia. Beijing has, I think, a complete inability to do self-introspection about how their own actions and statements are creating and stiffening the headwinds that they then shorten their time horizon. If you fire short-range ballistic missiles over Taiwan, I hate to say, that is going to have an effect in the conversation in Taipei, but also in Tokyo, also in Seoul, also in Canberra, and also in Brussels, in Berlin, in Ottawa, and London.

In the United States, I think it’s clear, as we were talking about a bit earlier, we’ve now artificially shortened our timeline by this, I think unscientific, analytically sound view that Xi Jinping is potentially going to launch some sort of kinetic strike this year, next year, in the next couple years. So, that is adding a sense of urgency artificially to the discussion. I think Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, if you’re following that line, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine only adds a sense of urgency of we can’t wait. And many people firmly believe that Xi Jinping has come to the conclusion that he needs to invade. And if you accept that basic mathematics, then, of course, your response would be, we need to throw everything at the kitchen sink now. And then just final comment quickly, and then I’ll shut up.

I think Taipei feels its own sense of urgency. One is it understands that U.S. attention is often fickle and it understands there is a moment of this post Ukraine invasion’s to try to lock in some U.S. support it. It’s a unfortunate reality that right now, Taiwan’s primary security comes from its relationship with the United States. And Taiwan has to manage that carefully. So, I understand. We’ve pulled the rug out from Taiwan before, and so I completely understand why they’re trying to go around and say Ukraine today, Taiwan tomorrow. But there is their own sense of urgency. So, you add this together and we just get this unfortunate situation, where instead of, again, thinking a little bit more calmly about this, we’re all sort of acting as if we got to come to a solution now.

Kaiser: Ryan, at the beginning of this conversation, we’d talk about how the Ukraine war was one of many of the factors in driving this new sense of urgency. It’s been close to 10 months now since February 24th. It’s struck me for some time now. I never seem to hear this out in public discourse that the Ukraine invasion, by this point in time, I should think, would serve to dissuade Xi Jinping from making a move on Taiwan. I don’t understand why we’re not saying that. I mean, you’d think that Beijing is looking at the economic costs of the potency, the sanctions of this kind of opprobrium, the pariah status to which Russia has been relegated. It would just be worse for China. Looking at the battlefield failures, just the duration of the fighting, none of it has got to be making Xi think, “yeah, let’s take our untested troops and invade Taiwan finally”. Am I missing something here? I mean, why is that not part of the conversation?

Ryan: Well, Kaiser, I think that to your and Jude’s point, we’ve predicted 10 out of the last zero Chinese invasions of Taiwan. It’s a habitual pattern of American analysts. And we should have a fair bit of introspection ourselves at why we keep on doing that. The issue of Ukraine matters significantly. I think it does a couple of things for China. One, I do think that it induces a bit of sobriety about the fact that the Chinese, despite their significant investments in military capabilities, can’t have absolute assuredness of the outcome of any conflict in the Taiwan Strait. A war in the Taiwan Strait would be orders of magnitude more complicated than any invasion by Russia of Ukraine. It would be significantly harder. The Taiwan Strait itself, just geographically, is three times wider than the English Channel, which we, during World War II, of course, during D-Day spent an extraordinary amount of time planning for because it was such a complex strategic challenge.

But Ukraine also has given the Chinese a free preview of the playbook that would be used against them in the event of conflict, maybe not military, but certainly economic. I think that the Chinese are taking exquisite notes, learning in fine detail what vulnerabilities in Russia’s system have been exploited, how they’ve been exploited, and what weaknesses they themselves may have. And so, what I think the real focus in Beijing is watching and reflecting upon events in Ukraine is how much further China needs to go to harden its own economy if it ever finds itself in a situation where it is at the end that Russia is on now in responding to international pressure.

Kaiser: But in recent months, it’s only been shown more and more examples of how vulnerable it actually is to things that haven’t been directed at Russia. It has its own unique set of vulnerabilities that have been on conspicuous display recently. Jude, you wanted to add something?

Jude: Just to maybe take a slightly modulated tack, I am also weary of us making determinations, one way or the other, what Xi Jinping is thinking about this. I mean, I’ve been in enough, and I know Ryan has as well, enough of these sort of meetings of lessons learned for Beijing. I find that… We don’t know, right? We don’t know. We have some visible outputs, which are articles that Chinese scholars, PLA scholars are writing that gives some indication of how they’re processing events. But states are not perfect lesson learning machines. Our foreign policy would be drastically different over the course of its history if it was constantly and accurately refining itself to the blunt realities of physics. I think we demonstrate, the United States, that we’re capable of consistently making mistakes.

Your podcast with Mike Mazarr is a great example of a lot of smart people can come to the absolute wrong conclusion about what the relative costs and benefits are. So, I would just say, I think this is one where we want to be incredibly cautious about coming to conclusion. It’s the only time I’ll ever quote Wittgenstein, but in the last line of his Tractatus, he said, “Where if one cannot speak, thereof one must remain silent.” I think we want to be looking, I think this is another really important thing to… I don’t think we would just see Xi Jinping cock-off, drink a shot of whiskey, and YOLO on Taiwan without first seeing him act erratically in lots of other policy areas.

So, we probably want to really be assessing Xi Jinping as a leader across the entire spectrum of policy. We want to go into this carefully. So, I guess I’m saying I think you guys are probably right, but I could have said the same thing about why Putin would not invade Ukraine because it was clear, given everyone was expecting this because it had been telegraphed that the costs were going to be significant, he was going to isolate Russia, and yet he did it anyway. So, I think we need to be somewhat agnostic on this.

Kaiser: Point taken. So, you guys write in your essay that fixating on invasion scenarios has us developing solutions to the wrong near-term threats; that we’re kind of path dependent. The guy with only a hammer in his toolbox, right? Or the drunk looking for the keys under the street light because that’s where the light is. Anyway, what scenarios are we planning around right now and why aren’t those the ones we should be planning for? I guess, I mean, that’s a better way, more direct way to ask is, what scenarios should we be planning for?

Jude: Certainly, some amount of our bandwidth needs to be thinking about a possible Chinese invasion. I don’t think we’re arguing that that drops to zero. I think what we’re saying is the proportion needs to be slightly different. First of all, there’s a scenario which is almost certainly coming up, which is future Speaker of the House, maybe it’s Kevin McCarthy, maybe it isn’t, travels to Taiwan sometime next year. And predictably, Beijing is going to respond pretty viciously, and in a way that’s going to try to undermine Taiwan’s resiliency and resolve; try to undermine U.S. credibility as a security partner. We’re also dealing with a near-constant state of Chinese economic and political coercion against Taiwan. Anyone who likes Kavalan whiskey will know that Beijing, just a few days ago, set another informal hard ban on the importation of Taiwan whiskey and wine.

Kaiser: That’s more for the rest of us.

Jude: Yeah, I guess. So, we’ve got a set of a pressing set of coercive activities that China is consistently leveraging against Taiwan to try to undermine Taiwan’s resolve. We’ve got an election coming in Taiwan in January, 2024. I’m certain we can expect a massive ramp up of interference by Beijing trying to delegitimize the integrity of that election. So, we’ve got this host of scenarios that are going to happen right now. And then just a final one is the PLA is young and inexperienced. It’s getting more sporty in and around the Taiwan Strait. We’re getting into closer proximity with the PLA. They do not abide by the same code of conduct and rules as the United States does. We’ve got very poor dialogue with China. So, we have a known quantity of the potential to have an unanticipated flareup, which would even, if again, even if we are in the right, still leaves us to try to clean up this mess.

Kaiser: But Ryan, surely these are things that we are planning around, are we?

Ryan: I’m confident that we are, but to perhaps put it another way, Kaiser, I think America’s interests are served by a strong and confident Taiwan. I think Beijing’s interests are advanced by a weak and insecure Taiwan. These are at odds with each other. And the more that we are hyping Taiwan’s inability to defend itself or advertising the latest war game in which we lost in cross-strait contingency, the more we’re really sort of doing a bit of Beijing’s work for them. They want the people of Taiwan to feel insecure. They want the people of Taiwan to feel like they have no alternative other than suing for peace. And so, what does that mean? What should we be doing? I think we should be doing things that help make the people of Taiwan feel secure and confident in their future — diversifying trade flows; ensuring that they are capable of acquiring the types of weapons that they feel that they need to protect themselves; helping encourage them and supporting them in stockpiling food, fuel, energy, medicine, munitions.

Helping to strengthen public health coordination so that the people of Taiwan don’t feel isolated and left apart from the global network that is fighting to beat back pandemics. Pooling resources to accelerate innovation so that Taiwan is a part of the growth story around clean energy or AI or some of these other emerging technologies. The government in Taiwan needs to provide for the health, the safety, and the prosperity of its people without feeling like they have to turn to Beijing to address those needs. The more that we’re capable of supporting that, the higher the likelihood that Taiwan will feel strong and confident about its future. This is why talking about the inevitability of conflict is so problematic from my perspective. Because it runs counter to the underlying objective of our overall strategy towards Taiwan.

Kaiser: You guys, I think that’s really the crux of the argument. I mean that we are, by focusing so singularly on the military dimension of this, we kind of crowd out the stuff where we should be putting more bandwidth into the kind of everyday persistent threats that Taiwan actually does face, the actual problems that we, we could be addressing. Yeah. I think you’ve done a pretty good job of cataloging what those threats are.

Jude: To add just one point, I think part of this would also be about what the United States doesn’t do or only does when it must, and with great focus and with a sense of what outcome we’re trying to achieve on this. There are a lot of times where it is necessary to probably provoke Beijing. There are times when not taking a necessary provocation is the more appropriate path. And I’m not sure we’ve entirely as a holistic policymaking and policy creating, U.S. government have quite figured out when it’s appropriate to poke and when we want to withhold. We have a divided government. It’s not a dictatorship. So, there’s agency amongst individual politicians that China is not dealing with. Some of this, an administration would have no control over. But I think having a better overall conversation on what our broad strategic outcomes are in regard to Taiwan that moves away from this idea of an invasion is the problem, the equation we’re solving more, more towards what Ryan was saying of what is a consistent, calm, strategically sound, and long-sided set of policies and actions the United States can take to better position Taiwan to continue to grow and prosper.

That, I think, would have downstream effects for what the options are that we should take, where we need to provoke, and where we might want to withhold provoking because it just gets in our own way and creates a more difficult situation for Taiwan.

Ryan: Jude, in the course of our conversations about this piece, he helped focus me in on a point that I hadn’t considered before, which is that all these substantive lines of effort that we’ve been discussing, they really haven’t aroused significant opposition from China. What has aroused significant opposition and upticks in tension are highly symbolic events that puncture Beijing’s narrative to their own people about the fact that Taiwan is moving closer to China. And those were Lee Teng-hui’s (李登輝 Lǐ Dēnghuī) visit to his alma mater, Cornell, in 1995, and Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August of this year. I think it’s worth bearing in mind that there is a pretty high level of space available to really driving forward on a lot of these substantive issues as long as we do it wisely with an awareness of where some of the tripwires or problematic areas may be.

Kaiser: That’s an excellent point. One of the other things that you guys warn against that you suggest that we not do is to cast the Taiwan problem as one of democracy versus authoritarianism. But at a fundamental moral and emotional level, I think that… Maybe I’m wrong. I mean, I daresay, that’s exactly how most Americans see this issue. What is wrong with that framing and how does that disadvantage us?

Ryan: Kaiser, I think that there are a couple of issues that come up in this context. The first, the more that we frame this as a democracy versus autocracy challenge, the more that it sort of validates Chinese worst assumptions about American intentions. In other words, that we would never countenance any resolution to cross-strait differences that were made between the leaders in Taiwan and leaders in the mainland because we are viewing Taiwan as a democratic asset to keep in our account. That will sort of accelerate us towards an outcome that our strategy is designed to prevent.

The second reason is that when these difficult dilemmas become cast in very moral dimensions, it gets harder for policymakers to act with nuance. It prescribes space and it sort of pushes policy makers towards absolute as black and white determinations. I don’t think that that’s typically healthy for policy, and particularly policy related, perhaps arguably the world’s most sensitive issue — Taiwan policy. I think it’s worth bearing in mind that the goal of America’s Taiwan policy is not to solve the Taiwan problem. It’s to prolong and elongate timelines so that eventually space is available for wise, cool-headed, farsighted statesmen in Beijing and Taipei to find a resolution themselves. And that requires a bit of a mindset shift because we, Americans, we like to have problems that are solvable, but Taiwan is just a problem without an American solution.

Kaiser: Yeah. You guys are inevitably going to encounter a lot of anger from folks who are going to allege that you have denied, once again, Taiwan and the Taiwanese people sufficient agency here, that their voices should be the only ones that ultimately matter in that casting. This in terms of U.S.-China relations inevitably relegates Taiwan to a passive role. It becomes just a pawn in this great power chess game. What would you guys say to those critics?

Jude: I think it’s extraordinarily important that as the United States is thinking about policy on this issue, that, of course, we’re always engaged with Taipei, that, of course, we’re always thinking about the distinct interests of the Taiwan people. And in fact, that one doesn’t worry me as much because I think this is one where the United States is incredibly attuned and engaged with Taiwan. What I would say though is from a just perspective of U.S. interests, our job is not to do what Taiwan wants us to. And in fact, what’s at stake here is an extraordinary expenditure of U.S. blood and treasure if this goes wrong. It is the basic math here that Taiwan’s security, in a large part, comes from its relationship with the United States, and that means the United States has a lot of skin in the game. There’s a lot at risk here.

While we always want to be considering the interests of Taiwan, we also need to preserve our own space for the United States to act in ways that, frankly, sometimes upset Taiwan. And it has always been, thus. It has always been the case that is a part of our one-China policy, the United States has to, at times, step in and anger Taipei to keep the peace. More often than not, we step in to anger Beijing to keep the peace by having a credible military deterrent. But we have consistently, and over and over again, needed to stress our own point of view and preferred set of actions precisely because we’re trying to keep the peace in a situation that could go volatile very quickly.

Ryan: Kaiser, can I just add one additional thought on top of Jude’s points, which I entirely agree with? Which is that what we’re talking about is encouraging efforts to make Taiwan strong and confident about its future. The opposite is selling a narrative of inevitable conflict that puts the United States’ in tension with the efforts of Taiwan’s leaders. President Tsai and her leadership team are trying to attract capital and talent to come to Taiwan. They’re trying to encourage high-skilled recruitment into their armed forces. Banging the drums of war is intention with the very objectives that the president herself in Taiwan has articulated.

Kaiser: That’s a very good point. Let’s talk finally about what form American support for Taiwan should take. I mean, it really, at the heart of this, and we’ve been talking about what a lot of these things should be, but at the heart of it, there is this adjustment or a clarification of just what the one-China policy should mean under these new circumstances. You do make clear that it’s just not good enough to repeat that our policy remains unchanged. As you guys correctly note, that rings hollow to anyone who’s actually been watching. Right? Nobody believes that our one-China policy is intact and has been especially over the last, what, six or seven years. How should we articulate what one-China now means to this administration to the next?

Jude: First, I think it’s important to disaggregate, and I don’t want to make a political comment here, but to disaggregate some of the loose discourse on what our Taiwan on policy is under Trump versus Biden. I think it’s just dramatically, dramatically different under the Biden administration. Under the Trump administration, not only did you just have just unprofessional looseness, and you had a lot of people, frankly, I just don’t think knew the basics of the issue. You also had this extreme moralizing Cold War component who I did, frankly, think wanted to sort of weaponize the Taiwan issue to drive a much more aggressive U.S. posture vis-à-vis China. That’s not what we’re dealing with under the Biden administration. I think, first and foremost, the frustration I think many of us have is it is not entirely clear, at a substantive matter, what this administration’s policy on Taiwan is.

And I think that comes from the top where we’ve had a number of statements from President Biden that would seem to be, in some ways, an important shift in U.S. policy of moving from a Taiwan Relations Act, understanding of what the U.S. bottom lines are in terms of keeping that space for us to be flexible on how we would respond in the event that China did take a more drastic action to compel through military means this political settlement, to something much more declaratory that, no matter what, we were going to stand with Taiwan. But it really wasn’t clarified and codified that there was a policy shift. So, it left a lot of us scratching our heads about, what did he mean? It was almost like Pekingology, but with Biden and administration characteristics, where it was like, did he mean it? Did he not mean it?

I have to say this may have been an attempt to deter China by putting this in the mix that the United States would take action, but I have to say, frankly, in discussions with our closest allies and partners, quietly, they were a little bit confused as to precisely what the new policy is. So, I would say, in terms of, reassurance of China is a dirty word, but I would say, in terms of reassurance, here’s the one big thing we have to do — have a clear consistent view on what our policy on Taiwan is, right? And let Beijing and Taiwan know that our policy remains exactly the same as it has in core substance, which is, as Ryan said, we’re not here… The solution to this ultimately is up to two of you. We just demand that it is peaceful and it takes into account the will of the Taiwan people.

Now, where I think Ryan and I do urge something proscriptive is what I think the Biden administration is having to deal with is the feeling that that sort of old formula needs to have a refurbishment; that we can’t just keep saying that we need to do a bit more because Beijing is, as we mentioned earlier in the piece, this isn’t the same PLA that we were dealing with 20 years ago. It has a much more area denial capability. It is taking steps, which two years ago would’ve been unthinkable; namely firing missiles over Taiwan. And so, I think there, what Ryan and I have said is instead of just pretending like our policy has remained unchanged, we need to more clearly link and clarify to Beijing that if you take actions, we are going to respond proportionately to reestablish the equilibrium. But I think that to do that requires A, credibility; B, consistency on your policy, and then a set of expectations for Beijing of, if you don’t do this, great. If you take these escalatory actions in these gray zone areas, we will be compelled to respond with countervailing actions, not because we’re trying to solve the Taiwan issue or rip Taiwan from any possible future political settlement, but because you have destabilized the equation.

Kaiser: But we want to maintain the balance. Right. Okay. That’s fantastic. I want to end this on maybe a slightly positive note. I’ve been talking with some Chinese diplomats, and there is a sense among them and among some of my American interlocutors that both sides are ready to dial down the heat a bit. There’s no real reproachment in the works or anything like that, but at least the goal of getting a floor under the relationship seems to be a shared one. And at the same time, I mean, we all saw after the Bali meeting, at the same time, the Biden administration initiatives that are already sort of in place are not slowing down at all, or not showing any size of letting up. They had some success in getting the Netherlands on board in limiting advanced chip-related equipment exports, adding a lot of Chinese companies today to BIS entity lists. So, what’s your own sense of this? I mean, if there are stirrings of a detente, what might be driving that, and how far could it go?

Ryan: Kaiser, I expect that in the next year, things will likely stabilize a bit relative to previous years. If you think of the slope of the relationship, it’s traveled a pretty sharply downward trajectory in recent years. I expect that that slope will probably flatten somewhat in the next year. I would be reluctant to suggest that the relationship will improve, because in order for the relationship to improve, we would either need to solve existing problems, agree to avoid future problems, or broaden the aperture of the relationship to dilute the sources of tension in it. And all three of those seem difficult in the current moment. But for each leader’s own reasons, I think that they have an incentive to dial down the heat a bit in the coming year. Now, of course, there could be external events that could intrude upon those plans. So, we need to predict a future with a high degree of modesty. But left to their own devices, my expectation is that both leaders will look for ways to inject a little bit more pragmatism and balance into the relationship in the next year.

Kaiser: Fantastic. Let’s hope it. I want to give you guys a couple of minutes to plug your podcast, Vying for Talent. Can you talk a little bit about the genesis of that and why you guys decided to collaborate on this?

Jude: Yeah. Well, thanks for plugging it. If we get one additional listener out of this, that will double our listenership, so we would welcome it. This emerged as discussions Ryan and I were having about how, and maybe this is similar to the foreign affairs essay of just trying to sort of shift the framing a little bit. That all of the discussion in the United States-China relationship seem to be this sort of race to the bottom of, how do we have a better industrial policy? What’s the next sort of set of arms sales or developments that can better position us? And I think it occurred to us that first of all, that really any of these issues, when you get to the heart of them, technology development, these are ultimately about which political system can create the best ecosystem to develop and nurture its talent, to bring in talent from overseas if it doesn’t have sufficient indigenous capacity here.

And so, the focus of the podcast in a larger project is really trying to center in on this issue of human capital and competing for human capital. I think what we sort of hope for is that also frames a bit of a race to the top dynamic, right? If you’re thinking about who can better develop and nurture and facilitate their own human capital, what you’re thinking about is, how do we better educate our workforce? How do we address, in China’s case, and anyone who’s read Scott Rozelle’s work would know China has a lot of work to do, to be able to take these rural areas and give them the same standard of living that people in wealthier urban areas have? I think we, in the United States, should absolutely welcome China developing that human capital base, both because that makes the world richer, and on an ethical level, that is, I think, a sort of core ethical good. So, we have no-

Kaiser: Not going to quote Kierkegaard.

Jude: No, Wittgenstein, by the way. Wittgenstein.

Kaiser: Oh, Wittgenstein. Okay.

Jude: I’ve never read Kierkegaard. Anyway, it’s just a modest attempt to think through some of these perhaps underappreciated elements of this very complicated bilateral relationship.

Kaiser: Fantastic. Yeah, give it a listen. It’s great. Start with the interview you guys did with Morris Chang. You’ll be hooked on that. And come on, man. I’m a listener. There’s got to be more of you out there. I’m going to skip the usual plug I do, but you know the drill, if you want to support what we’re doing, subscribe to our damn newsletter, and moving on to recommendations. Recommendations is my favorite little segment of the show. And I’m really keen to know what you guys have. Ryan, why don’t you start, and then Jude?

Ryan: Well, Kaiser, if it’s all right, I’m going to throw in two quick recommendations. One serious…

Kaiser: Oh yeah, absolutely.

Ryan: One serious and one sentimental. The serious one is a piece recently by John Culver, a former National Intelligence Officer for Asia, who wrote for the Carnegie Endowment, “How we would know when China is preparing to invade Taiwan.” And he applies 35 years of hard-nosed efforts of analyzing China to break down what indicators and warnings would look like that would tell us that China is traveling on a path leading eventually to conflict. So, I highly recommend that.

Kaiser: It’s a great piece.

Ryan: It’s fantastic.

Kaiser: No, absolutely. Yeah. I’ve passed that around to a hundred people already, but…

Ryan: Well, it deserves it. And on the sentimental side, I’m going to recommend White Christmas, the movie. It’s a movie I watched with my parents when I was young. And now that I’m a parent of four kids, it’s something that I enjoy doing with them this time of year as well.

Kaiser: All right. I need a good Christmas movie right now. Yeah, that’s good. I’ve not seen White Christmas. Is that we’re Bing Crosby sings?

Ryan: It’s Bing Crosby and Rosemary Clooney. You’re just pulling for them to get together by the end.

Kaiser: Okay, fantastic. All right. Jude, what do you have for us?

Jude: I’ve got one podcast, but two seasons, so I don’t know if that counts as two recommendations, but I stumbled across a podcast called In the Dark, which is American Public Media. Season one is about murder investigation of Jacob Wetterling, which happened about 30 years ago and was unsolved until very recently. And it’s utterly gripping, compelling. And it’s an investigation of how broken our criminal justice system in, but especially local policing, by sheriffs, and how little scrutiny there is of their actions. And season two build on that, which is about the wrongful conviction of Curtis Flowers in Winona, Mississippi. And he was tried six times for the same crime by one district attorney. He was black, the district attorney was white, and it… I don’t want to spoil the ending but both seasons are totally engrossing and gripping on a human level.

Season one, as the father of a child, just what the family went through, especially the agony of a broken judicial system, under-resourced, but also isolated from, largely from scrutiny because local media is dead in the United States. So, much of this activity isn’t picked up unless a reporter starts a podcast and gets resourced. And then the second one is just the inequity built into the judicial system where you think “there but for the grace of God go I”. And you see the machinations of what should be a fair, transparent judicial system when a spotlight is shown on it. It’s horrifying and it should be a cause for national alarm. So, as we think about these massive geopolitical issues thousands of miles away, it just again, emphasizes how much damn work we have to do here in the United States, probably within a stone’s throw of wherever any of us are listening to this podcast.

Kaiser: Yeah, yeah, yeah. All right. For my recommendation, look, I mean, two of you, both of you have been load stars for me in so many ways. You guys are doing God’s work out there. But if there’s one, I mean, and there are so many other people who I could name check as well, but if there’s one person who has just been especially heroic, especially just in the last couple of years, it’s Jessica Chen Weiss, who has been, I’m glad to say a guest on the show on a couple of occasions. Ian Johnson, who is one of my absolute favorite writers. He’s now at CFR, but still writing for the New Yorker, has just written a profile on Jessica in the New Yorker, and I highly recommend it. It’s a great piece. It really captures her well, what she’s up against and the good sense that she’s been making. Really just couldn’t recommend it more highly. Great, great, great piece. And so, with that, I know we were a little bit over time, but thank you so much for taking the time to join me, Jude and Ryan.

Ryan: Thanks Kaiser, it was great to be on with you.

Jude: Thank you, Kaiser.

Kaiser: The Sinica Podcast is powered by The China project and is a proud part of the Sinica Network. Our show is produced and edited by me, Kaiser Kuo. We would be delighted if you would drop us an email at sinica@thechinaproject.com or just give us a rating and a review on Apple Podcasts as this really does help people discover the show. Meanwhile, follow us on Twitter or on Facebook at @thechinaproj, and be sure to check out all the shows in the Sinica Network. Thanks for listening, and see you next. Take care.