The Big Four auditors may lose state-owned business in China — would it actually hurt them?

Nearly a quarter of China’s 98 central state-owned enterprises were audited by KPMG, PwC, Deloitte, or Ernst & Young in 2021. They might lose these customers, which would be a bad look, but perhaps not terrible for their bottom lines.

Major Western accounting firms established a dominant presence in China soon after they were first permitted to operate there in the 1990s. The “Big Four” accounting firms now regularly sit atop the Chinese Institute of Certified Public Accountants’ (CICPA) rankings of firms.

But the China-based branches of the Big Four firms (KPMG, PwC, Deloitte and Ernst & Young) could find the competition chipping away at their dominance in the near future. Last week, Bloomberg reported that China’s Ministry of Finance had given so-called window guidance to Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs), urging them to phase out their use of the Big Four for auditing services, citing risks to data security.

No deadline has been given, and authorities have made similar suggestions in the past, perhaps indicating that the four firms don’t have too much to worry about just yet. On the other hand, the Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 administration has been keen to limit the activity of foreign firms in various sectors in the name of data security. The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) launched an investigation into ride-hailing company Didi Chuxing in 2021 after it listed in New York, partly over fears of data leaks. Major SOEs have in recent years delisted from the New York Stock Exchange, in part to avoid having their books inspected by American regulators under a new deal between the U.S. and China.

Companies that switch to homegrown auditors may find approval among Chinese policymakers, but could also face some loss of confidence among foreign investors or partners due to fears that local auditors may not be as reliable or independent.

Given recent delistings of major SOEs, however, the calculus behind ideal auditors may have shifted. Being delisted means the SOEs have to worry less about negative investor reactions if they switch to homegrown Chinese auditors. China Eastern Airlines and China Southern Airlines, the last two SOEs listed in New York, announced in January that they would also delist.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

Still beancounting after all these years

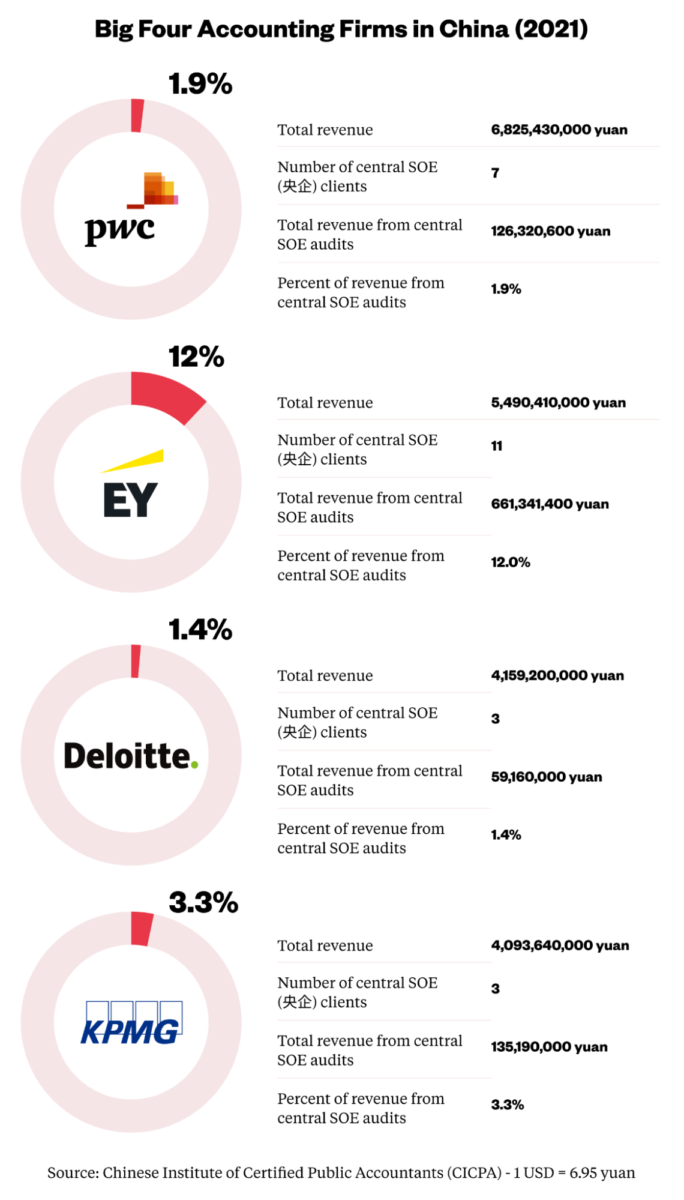

The Big Four remain a dominant force in China’s accounting industry. Rankings for 2021 by CICPA (which take into account a number of factors including but not limited to revenue) showed the firms in the top four places, with combined 2021 revenues exceeding 20 billion yuan ($2.9 billion). The Big Four conducted audits for 24 of China’s 98 central SOEs in 2021.

Still, the audits of the central firms only make up a fraction of the operations of the Big Four. CICPA data revealed that a loss of business from major state-owned firms would likely affect each of the major audit providers quite differently. The data shows that Ernst & Young’s China operations could stand to lose out the most if its central SOE clients switched to other auditors, with around 12% of its revenues coming from audits of the 11 such firms it served in 2021. Meanwhile, PwC, Deloitte and KPMG had lower shares of their respective revenues coming from audits of central SOEs.

The CICPA data did not take into account any audits the firms might provide for other state-owned companies in China that are not centrally administered. The auditors could be affected differently depending on the extent of their business with these smaller SOEs, and whether or not Chinese authorities eventually require all SOEs to use homegrown accounting firms.

CICPA data from 2020 showed that for all four companies, business with the central SOEs trended downward the following year.

The Big Four are likely taking steps to stay on Beijing’s good side and keep their SOE clients. Shortly after Bloomberg reported on the new guidelines, the Financial Times revealed that Ernst & Young’s Communist Party branch committee had asked employees that are Party members to wear Party badges.

The China-based branches of the Big Four did not respond to requests for comment.

Chinese media pushes back

Chinese state-controlled media outlets, for their part, pushed back against Bloomberg’s claims. The Global Times “refuted” the claims by pointing out that state-owned firm China Taiping Insurance recently awarded a contract to PwC (the article also pointed out that China Taiping Insurance is the only SOE headquartered outside of mainland China, as it’s Hong Kong-based).

Other Chinese media joined in, citing other reasons why the Bloomberg report might be false, such as China’s frequent proclamations that it opposes decoupling and recent efforts made by China’s government to boost the confidence of foreign investors in Chinese companies through the recent bilateral audit deal.

What these media reports don’t mention is that when it comes to SOEs, Beijing has in fact been more likely to decouple; as the 2022 deal to allow U.S. regulators to inspect Chinese companies listed in the U.S. took shape, major Chinese SOEs delisted from the New York Stock Exchange, in what many saw as a move directed by Beijing.

Who stands to gain?

Major Chinese accounting firms with the resources to audit large companies likely welcomed the news that officials had urged SOEs to switch auditors. Among these firms is BDO China Shu Lun Pan, which in 2021 had the third highest revenues among accounting firms in China, beating out KPMG and Deloitte. It also audited more central SOEs than any other firm, 19, demonstrating its capacity to take on the massive clients.

Other large accounting firms that could benefit from the move include Baker Tilly’s China operations, which had 18 central SOE clients in 2021, and China-founded firm ShineWing, which had 11.

Domestic Chinese accounting firms have been trying to take market share from the Big Four for years, often with the help of officials. In 2007 the CICPA began strategizing to foster ten world-class accounting firms capable of serving Chinese firms abroad, and in 2010 regulations were passed to ensure SOEs and financial institutions regularly switched auditors.

But the measures didn’t always pan out as expected. When forced to change auditors, many SOEs simply switched from one Big Four firm to another, rather than picking domestic firms. For many of the largest SOEs, audits of their sprawling, global operations require skills and resources that some domestic firms simply lack. Despite some predictions that by now the Big Four would have lost their vaunted place as the biggest players in China’s industry, they remain on top of CICPA’s rankings.

This isn’t the first time the Big Four have been at the crux of U.S.-China tensions. In 2012 the four firms came under fire after refusing to hand over documents to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), citing Chinese data security laws, which if violated could result in life sentences. Their auditing practices have also been called into question when major Chinese firms listed in the U.S. have been exposed as fraudulent. Ernst & Young was criticized after a major scandal involving China’s Luckin Coffee, which it audited, and which fabricated revenue numbers in 2019.

The takeaway

With the delisting of major SOEs from American exchanges, Beijing has shown that it’s serious about the data security of its central state-owned firms. This resolve may portend a change who gets to audit the firms. For Ernst & Young, the loss of major SOE clients would sting more than for its fellow Big Four firms.

Companies:

Sources and additional data:

- ‘Big Four’ Accounting Firms Still Favored by Some China State Firms / Caixin

- 四大会计师事务所被敦促不与国企合作?究竟怎么回事儿?/ 网易

- Exclusive: Media claims of China phasing out ‘big four’ accounting services refuted; new auditing projects awarded in recent days / Global Times

- Big Four auditors squeezed between US and China / Financial Times

- Ernst & Young Says It Isn’t Responsible for Luckin Coffee’s Accounting Misconduct / Wall Street Journal

- China investigates Didi over cybersecurity days after its huge IPO / Reuters