U.S. semiconductor export controls might actually give China the edge

China’s semiconductor wafer fabrication companies are way behind their Western and Japanese peers. But new multilateral export controls targeting China may actually push Chinese firms to innovate their way into the big league.

In October 2022, the U.S. Commerce Department announced what is arguably the Biden administration’s most consequential policy to date. The U.S. put in place export control measures limiting China’s access to U.S. semiconductor technology on national security grounds. These effectively deny China access to the most advanced computer chips, and to the software and equipment that are needed to produce them.

In March 2023, encouraged by the U.S., the Japanese and Dutch governments followed suit and announced their intention to issue licensing requirements for exports of advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment. When they come into effect, these measures will include immersion deep ultraviolet (DUV) lithography tools, drastically widening the range of restrictions on selling to China.

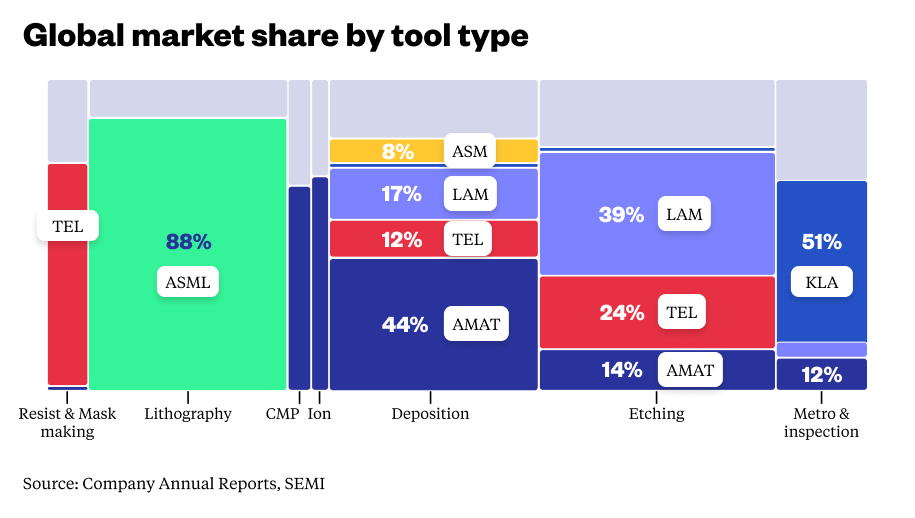

This tripartite coordination was deemed necessary, as the three countries involved are home to the largest wafer fabrication equipment (WFE) manufacturers in the world. The primary targets of these regulations, Applied Materials (AMAT), ASM, ASML, KLA, Lam Research, and Tokyo Electron (TEL), account for over 80% of the total supply of semi equipment worldwide. Without access to their most sophisticated tools, China is virtually incapable of producing any of the leading-edge chips that are needed for the development of AI or 5G.

China did not idly stand by as those events transpired. A couple of months after the United States imposed export restrictions, the P.R.C. filed a complaint with the WTO claiming that the U.S. policy violated various international agreements on trade, tariffs, and IP. In May 2023, Beijing ruled that companies operating in “critical information technology infrastructure” ought to stop purchasing chips from Micron.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

China has also taken significant steps to prop up its domestic semiconductor industry. Toward the end of 2022, the government earmarked $143 billion to bolster the domestic semiconductor market over a five-year period. Several municipal and provincial governments announced similar initiatives, with Guangzhou setting $29 billion aside for investments in tech, including semiconductors.

Pundits have since been opining on what China’s next move might be in the “Tech Wars,” invoking options ranging from protectionist tit-for-tat measures (e.g., blocking the export of rare earths) to cyberattacks. A more interesting set of questions to ask, though, would be why there is such a dependency on foreign-made equipment to begin with, and what the consequences of prompting China to double down on the development of its WFE ecosystem will be. China was, after all, able to build the world’s largest automotive market from scratch, and more recently to attain global leadership across most of the electric vehicle (EV) ecosystem. Will it be able to replicate that success in the semiconductor space now that push has come to shove?

Late to the party

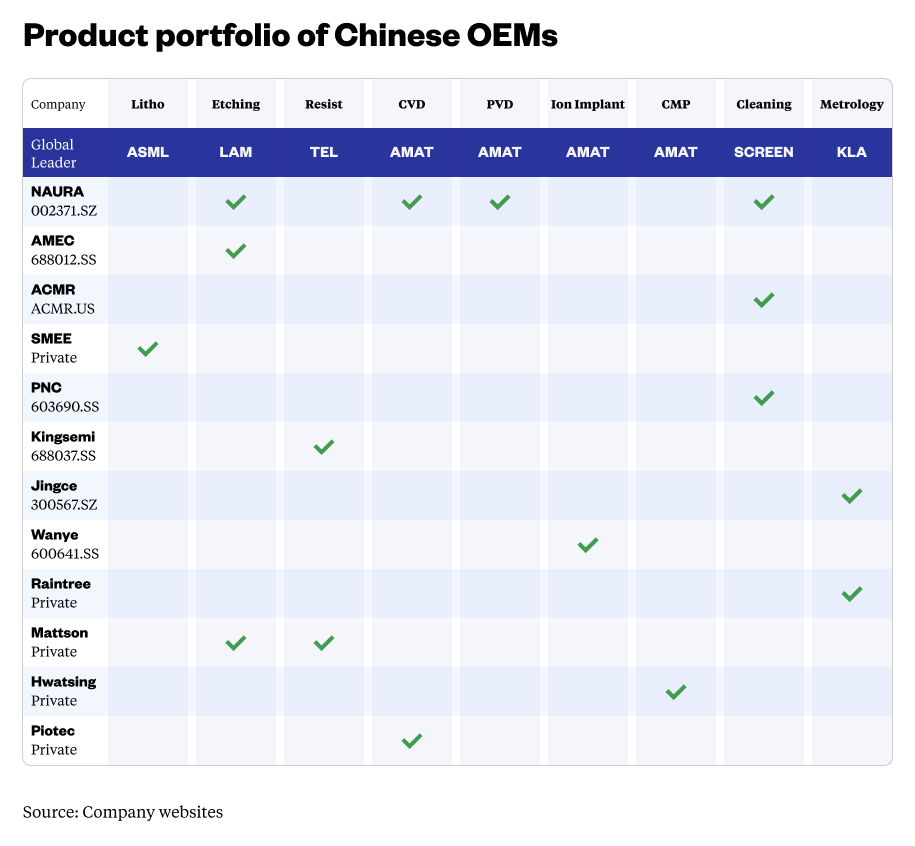

While the most prominent global WFE original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) boast a 40- to 50-year history, the Chinese semiconductor equipment industry didn’t emerge until the noughties. In 2006, the Chinese government launched the VLSI Fabrication Technology Research Program, to accelerate the growth of local semi technology. The program offered grants to semiconductor capital equipment (semi-cap) applicants that conducted research on specific areas related to semiconductor manufacturing. As each research project covered a distinct area of the semiconductor manufacturing process, there was little overlap between local semi-cap OEMs, which collectively covered most equipment categories in wafer fabrication.

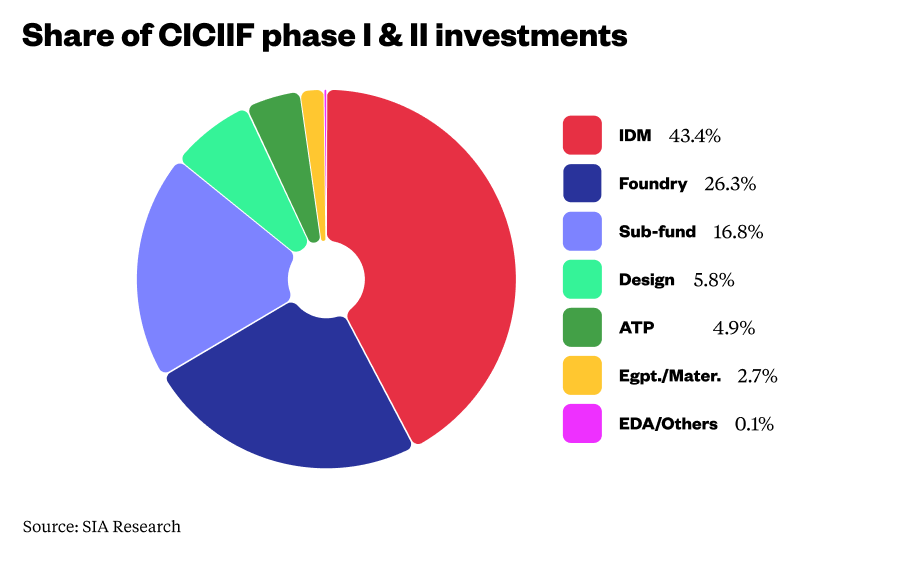

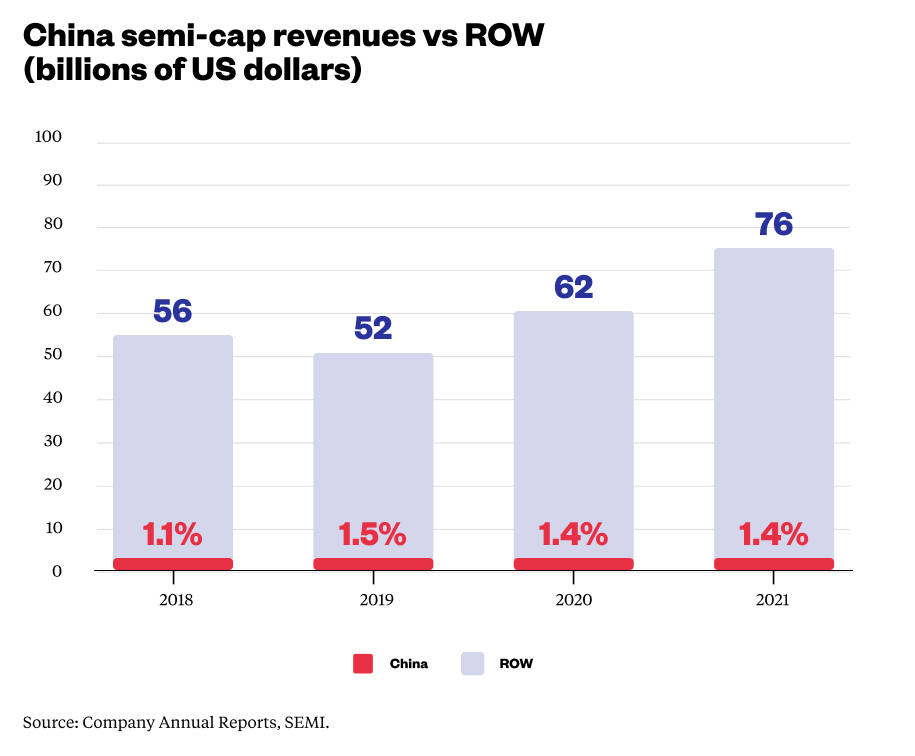

In the years that followed, successive Chinese governments elevated their aspirations for integrated circuits (IC) autonomy to the country’s Five-Year Plans. To become self-sufficient, China resorted to industrial policies. It set production goals, offered subsidies and tax benefits, erected trade and investment barriers, and promoted foreign-domestic joint ventures. It also created the China Integrated Circuit Investment Industry Fund (CICIIF) which channelled approximately $150 billion of state aid to the broader silicon space. Only a meagre 2.7% of those funds were directly allocated to semi-caps. Foundries and IDMs were the recipients of the bulk of the CICIIF funds and deployed them in capital expenditure, R&D and to acquire foreign companies. Bruegel estimates that, as a result, between 2014 and 2018 Chinese chipmakers were the most heavily subsidized in the world by a very wide margin. Their capital expenditures, however, did not seem to have benefitted domestic toolmakers much. China still imports most of its WFE from foreign suppliers and Chinese toolmakers account for less than 2% of the global equipment market.

A vicious cycle: the technological gap in Chinese semiconductor equipment

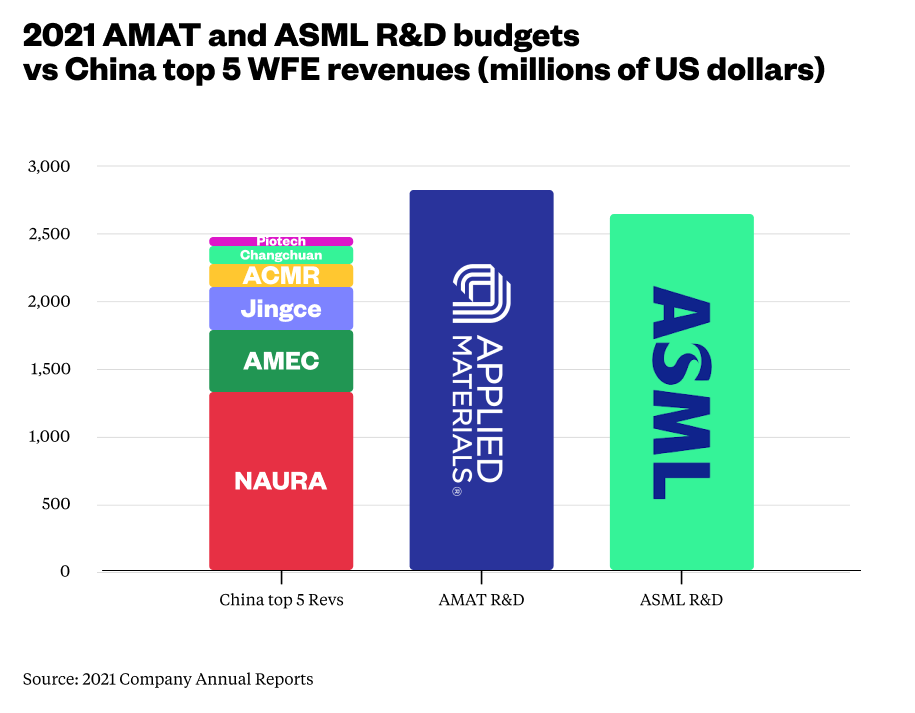

Casting capital allocations aside, the limited progress made by Chinese toolmakers is primarily attributable to an enduring technological disadvantage versus their foreign peers. In lithography for example, the sole Chinese lithography firm, Shanghai Microelectronics Equipment (SMEE), can only produce machines that print down to 90nm patterns and whose actual use in mass-production is unverified. In comparison, ASML is expected to start shipping its 2nm machines by the end of 2023. Bridging this gap becomes all the more challenging when considering the difference in scale between Chinese and world-leading OEMs. In 2021, Applied Materials’ R&D expenditures were higher than the revenues of the five largest publicly listed Chinese semi-caps combined. By leveraging their scale and experience, foreign semi-caps are able to at the very least maintain their technological advantage and at best expand it.

Moreover, international OEMs have historically relied on a deep and wide network of tier-1 suppliers that produce subsystems and components that are critical to the development of more precise chipmaking tools. ASML, for example, worked alongside a few thousand suppliers to develop its EUV systems, effectively outsourcing capex, opex and most importantly R&D. The latest lithography machines are only technically viable because of Zeiss mirrors, Trumpf power sources and Edwards vacuum systems. There currently isn’t an equivalent tier-1 ecosystem in China, especially for very niche mission-critical technologies that lack applications outside of the semi space.

These factors create a vicious cycle for Chinese semi-caps. Their small scale hinders their ability to invest in meaningful R&D and attract tier-1 suppliers. This in turn keeps their technology lagging behind global leaders and makes them uncompetitive. Ultimately, this absence of technological parity results in a low adoption of made-in-China tools by domestic chipmakers, who are unlikely to source equipment locally if doing so negatively affects their production yields and operating costs. The lack of real-world operating experience that ensues exacerbates the difficulty of developing new tools and maintains the existing technological gap.

The first innings of a virtuous cycle?

Historically, Chinese chipmakers had been hoarding foreign-made WFE in anticipation of restrictive trade measures. This was known in the industry as ‘non-market demand’, a term used to describe artificial demand dictated by a strategic need to amass as many tools as possible while they were available. When the U.S. started drawing plans for export curbs on toolmakers, however, the nature of this artificial demand was reversed. There is now excess demand for made-in-China tools, as they are effectively the only option for China to equip fabs for mature nodes without being overly reliant on American policy whims.

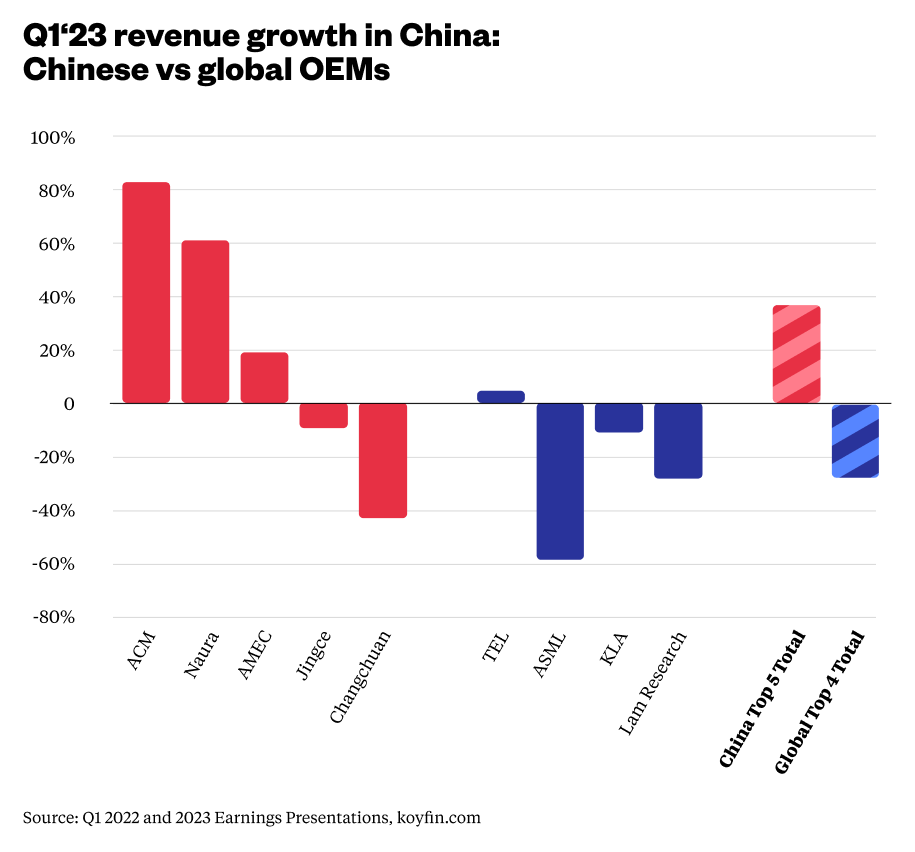

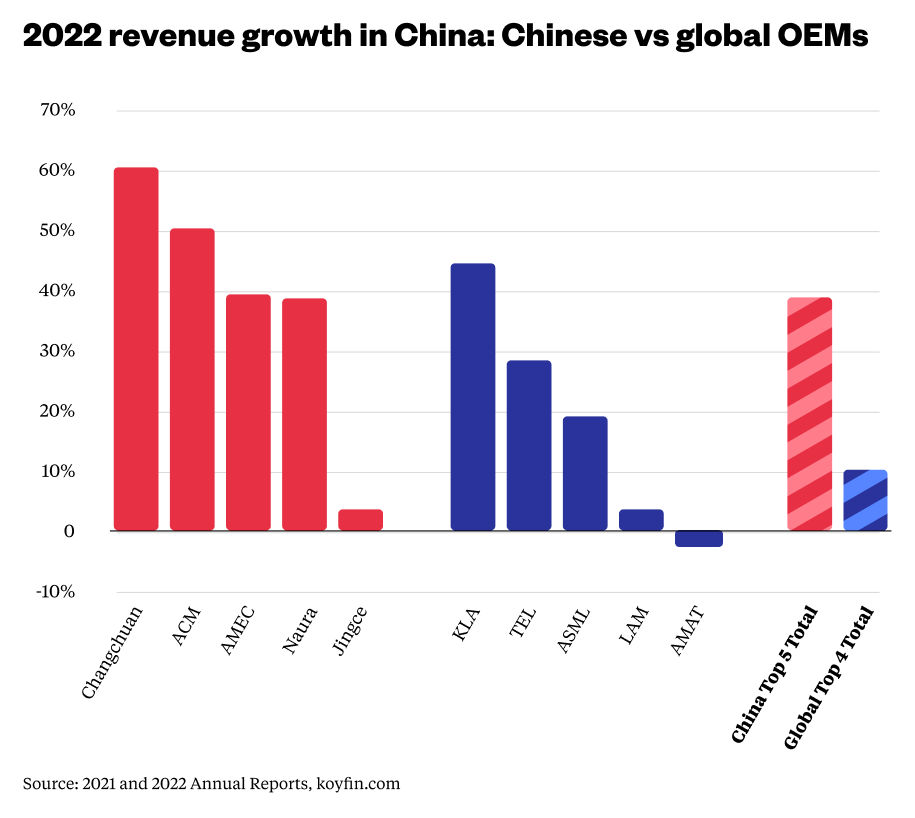

This pivot predates export controls. In 2022, Chinese OEMs outgrew their global rivals by 27 percentage points, indicating that even before global semi-caps started withdrawing part of their product offering from the Chinese market, local suppliers were stepping in to supplant them. This trend picked up steam after the trade ban. In the quarter to March 2023, the five largest listed Chinese OEMs reported growth of 35% whereas the global top four contracted by 28% in China (this figure excludes Applied Materials which did not report China figures).

This trend is expected to continue ; Lam Research, Applied Materials and KLA have provided negative growth guidance for the quarter to June ’23 in their most recent earnings calls. Last year, they had warned that they could stand to lose up to $5 billion worth of revenue from China in 2023. In comparison, ACM Research, the only US listed Chinese WFE OEM, expects to grow revenues by 32% to 50% this year. Their domestic peers are projected to witness similar growth, aided by more targeted industrial policies and expanded trade sanctions. In a WFE market that is expected to contract from roughly $100 billion in 2022 to somewhere in the $70 to $80 billion range this year, that translates to a net share gain for the Chinese WFE sector. This presents an unprecedented opportunity for Chinese OEMs to increase their footprint within domestic fabs at the expense of their foreign rivals and to gain the real-life operating experience they so desperately need to develop their technological capabilities.

For the time being, lagging technical capabilities have constrained this share gain to tools for the fabrication of mature nodes. Even so, export controls appear to have accomplished what two decades worth of industrial policy had failed to achieve: driving the development of the Chinese semi-cap industry. One can’t help but wonder if this development will eventually extend to the leading edge and thus inadvertently usher in a virtuous cycle for the Chinese IC market.

The lithography hurdle

To produce smaller nodes, TSMC, Samsung and Intel have largely relied on EUV lithography tools produced by ASML. EUV technology uses shorter wavelengths and reflective optics to create smaller features on silicon wafers with fewer processing steps than DUV, making it a critical tool for the semiconductor industry to continue shrinking the size of transistors and other features on microchips.

While it is technically possible to manufacture advanced chips using alternative lithography techniques such as multi-patterning, it is highly unlikely that Chinese fabs will be able to efficiently do so without EUV or immersion DUV technologies.

ASML began developing EUV lithography technology in the late 1990s. It took the company about two decades of research and development to bring EUV technology to commercial viability. The only Chinese domestic alternative to imported advanced lithography tools in China, SMEE, is at least ten years behind. It is hard to imagine how SMEE might be able to bridge that gap given the lack of utilisation of its tools, but also considering the lack of engineers with experience in lithography and of tier-1 suppliers to support their development.

The takeaway

Wafer fabrication equipment had historically been the neglected sibling in the broader Chinese semi landscape. While inroads were being made in areas such as assembly, testing and fabrication, Chinese equipment consistently trailed far behind that of global OEMs, in both technology and market share. This course is being reversed by trade sanctions that intrinsically link Chinese IC self-sufficiency to the development of locally produced chipmaking tools. Most local fabrication equipment manufacturers are already benefiting from a larger serviceable market in mature nodes created by the changing geopolitical landscape. However, it is unlikely that that opportunity will extend to the leading edge in the near future because of the substantial technological gap in lithography.

The export curbs will have a positive effect on Chinese semiconductor self-sufficiency, but that will be limited to chips used in cars, servers or domestic appliances. The aspiration of building a fully autonomous ecosystem capable of churning out advanced ICs is still well beyond the capabilities of the current semi-cap supply base.

Companies

Shanghai Microelectronics 上海微电子

Advanced Micro-Fabrication Equipment Inc. China 中微半导体

ACM Research 盛美上海

Kingsemi 心愿微电子

Jingce 精测电子

Accotest 华峰测控

Hangzhou Changchuan 杭州长川科技

Piotech 拓荆科技

Wanye 上海万业企业

Raintree 睿励科学仪器

PNC 至纯集成

Hwatsing 华海清科

Sources and additional data

China’s New Strategy for Waging the Microchip Tech War / CSIS

Examining China’s Semiconductor Self-Sufficiency: Present and Future Prospects / Semiconductor Industry Association

Lessons for Europe from China’s quest for semiconductor self-reliance / Bruegel

China gives chipmakers new powers to guide industry recovery / Financial Times

The big question of how small chips can get / Financial Times

Tech war: Guangzhou pours US$29 billion into funds for semiconductors, other hi-tech fields as local governments boost China’s recovery / South China Morning Post

Exclusive: China readying $143 billion package for its chip firms in face of U.S. curbs / Reuters