America’s convenient territories: How Washington is preparing to duel Beijing in the Pacific

China is constructing artificial islands in international waters, but the U.S. is also building its presence in far-flung American territories in the Western Pacific way beyond the "logo map" of the lower 48 states. Laurel Schwartz checked in with elected officials from the region.

As a flurry of cabinet-level secretaries traveled from Washington, D.C., to the Pacific Rim over the past few weeks, China and the Town columnist Laurel Schwartz has been sticking around inside the Beltway, dissecting how this friend-shoring offensive is being spun at home.

In July, U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin traveled to Papua New Guinea, the first sitting U.S. Defense Secretary to do so. Also in the region was Secretary of State Antony Blinken, whose visit to Tonga marked the first time a sitting U.S. Secretary of State visited the island nation with a population of just over 100,000, about the size of the tiny city of Green Bay, WI. In August, President Biden hosted Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol at Camp David, their fourth meeting over the past 14 months.

To get an idea of the tenor of America’s Western Frontier in the East, I interviewed Representative James Moylan (R-Guam) and Representative Aumua Amata Coleman Radewagen (R-American Samoa).

What are the stakes?

Spinning the message for these visits were Assistant Secretaries Daniel Kritenbrink from the Department of State, Ely Ratner from Defense, and Rozman Kendler from Commerce. They popped up at a sparsely attended hearing on Capitol Hill, testifying to the House Select Committee on Strategic Competition between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party about the “Biden administration’s P.R.C. Strategy.” (Committee Chairman Representative Mike Gallagher joked that his “initial request was for six or seven Cabinet-level officials” instead of their deputies).

The members, eager to provide sound and video bites, employed everything from images from the recent Barbie movie to surprisingly malicious personal insults. After the bureaucrats gave thorough testimonies about how their departments were friend-shoring, building up military deterrence, and implementing trade policies that would limit intellectual property theft and corporate espionage, members asked monologue-like questions.

One Republican member drilled Commerce’s Assistant Secretary Rozman Kendler, the only woman testifying, about the dangers of a trade deficit with China. “Your policy, Ms. Rozman, helps the Chinese government. Your inability to answer my first question tells me you don’t care,” he said. “Do you understand the Chinese are the biggest bully on the planet? They determine the rules on the playground.”

Hours after the hearing, Ambassador Joseph Yun, lead negotiator for Compacts of Free Association (COFA), attended an event at the conservative Heritage Foundation, where he discussed how economic and military agreements with small island nations in the region are critical to countering Chinese influence in the Pacific Islands. The event was open to the public, but I was required to show my ID at the door to confirm I had registered in advance. My bag was searched, and I was informed that I wasn’t allowed to bring any drinks, including water, into the event. Security guards were conspicuously posted around the half-full auditorium.

As I munched on the free lunch afterward, I chatted with a retired Cold War–era diplomat who had previously worked in the region. What did he think we needed to do to prevent World War III?

His affable face turned serious over our turkey sandwiches and chocolate chip cookies. The largest threat, he said, was the U.S. electing another “unpredictable leader,” apparently referring to President Trump.

I probed. How do you get voters to understand the stakes?

“I don’t know how you get people to understand the consequences of a nuclear apocalypse,” he said flatly.

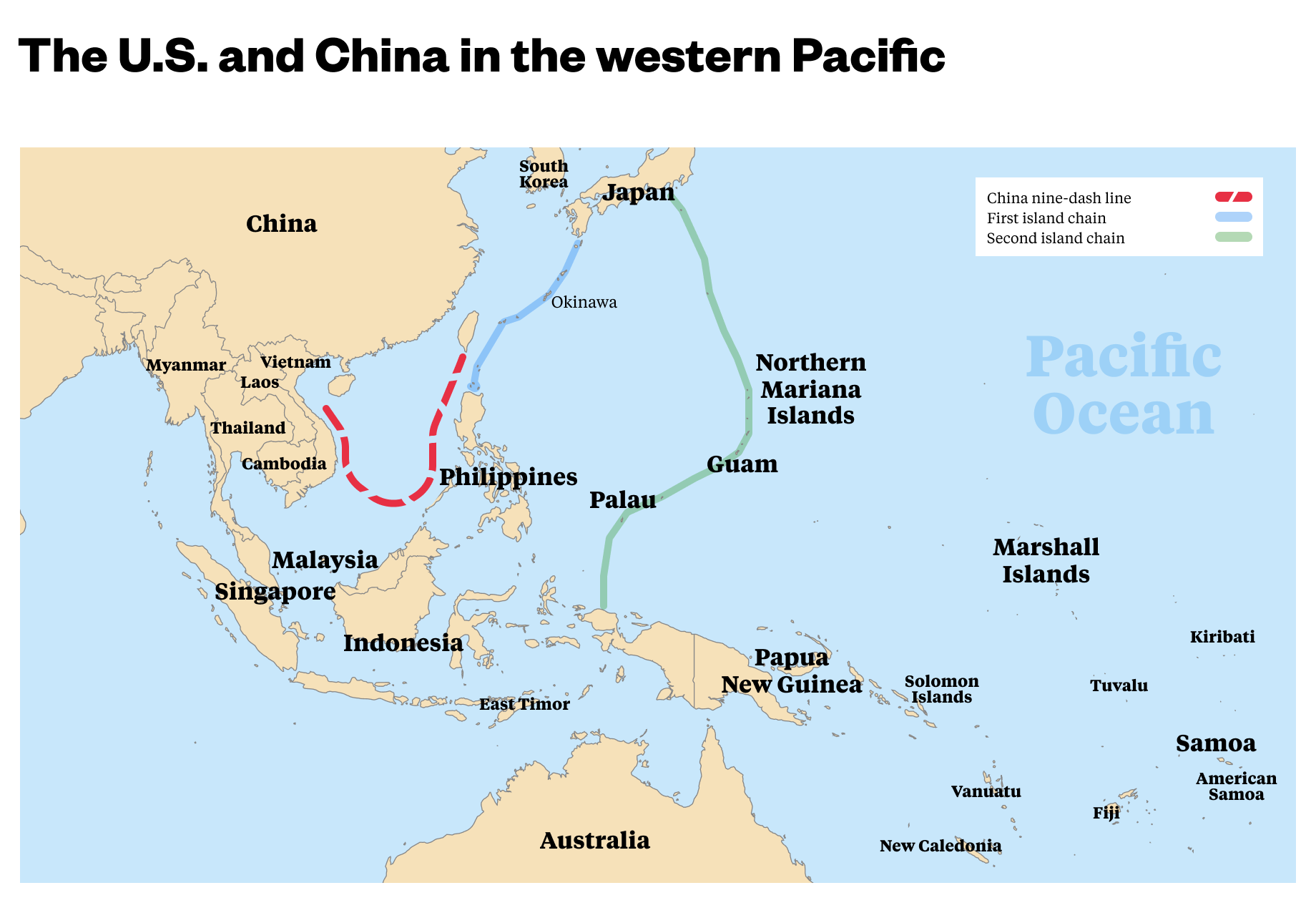

Map for The China Project by Alex Santafé

Assistant Secretaries Kritenbrink and Ratner continued the roadshow on their own terms the next day at the Brookings Institution, where their audience of policy wonks, reporters, diplomats, and grad students filled the main auditorium and an overflow room (coffee and water flowed freely, but there wasn’t a free lunch afterwards).

UCLA public policy grad student and D.C. native Christian Gershard pushed the senior officials on American soft power and lasting impact in the Indo-Pacific. “Whether those were failures or successes, the memory of the misuse or failed [U.S.] approaches still stand in the region. How can the U.S. establish itself as a nation of conscience in the Indo-Pacific?”

“We’ve been an Indo-Pacific power for well over a century,” Kritenbrink responded. He referenced his time as the U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam. “Even with countries with whom we share a very painful and sometimes tragic past, there too we’ve made really dramatic and historic strides to overcome that past. And in the case of Vietnam, for example, we’ve built this amazing partnership and friendship together, even as we continue to work on those legacy war projects.”

Speaking from the Pentagon’s perspective, Ratner emphasized the choice between rule of law and freedom versus coercion. “We’ve spoken a lot about the shared vision we have for a free and open Indo-Pacific. The P.R.C. is putting forward an alternative vision…through their unsafe operational behavior…against maritime and aircraft that are operating in accordance with international law…We see them engaging in other forms of corruption and influence throughout the region. Countries throughout the region have a choice of which type of order they want to live in.”

Guam is in the line of fire

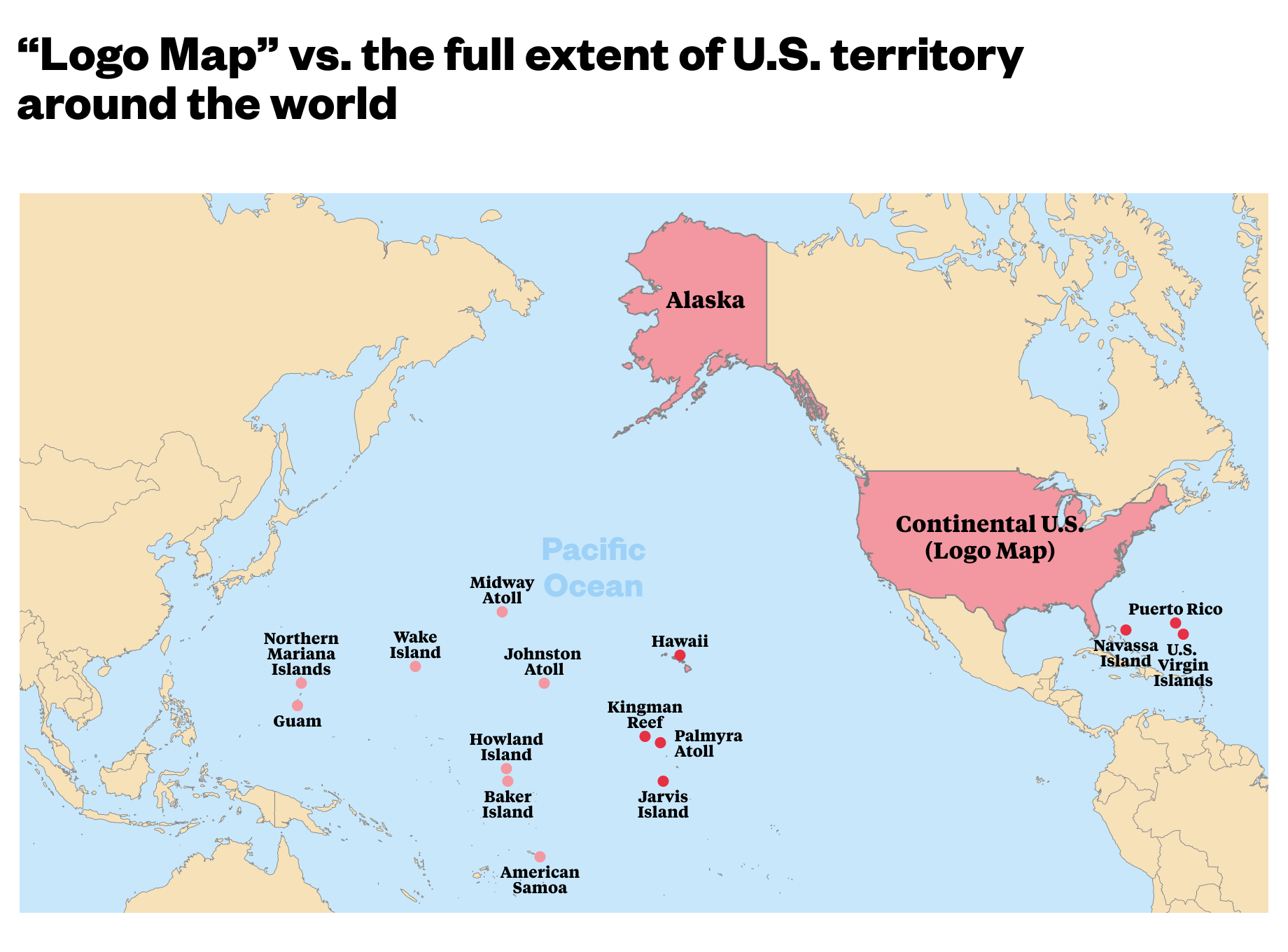

Just in case countries in the region don’t choose the U.S. vision, Washington is fortifying its sovereign ground all around the world. This includes parts of the world that many Americans don’t even think of as American, way beyond the so-called “logo map,” spanning the International Dateline.

Map for The China Project by Alex Santafé

In every public wargame scenario between the U.S. and China, the first victim of a Chinese attack is Guam, a U.S. territory almost two times closer to China than to the U.S. Mainland.

Guam, the closest American soil to the Asian mainland, has had a strong U.S. Military presence since it was put under the jurisdiction of the Navy when it was acquired by the U.S. in 1898.

The threat of being on the frontlines of an Indo-Pacific hot conflict isn’t an abstraction to freshman Republican Rep. James Moylan, the non-voting delegate from the U.S. territory of Guam. As we sat in his wood-paneled D.C. office, almost 8,000 miles from his district, Rep. Moylan emphasized the importance of being on strategic committees. He is the first delegate in four years from Guam to serve on the House Armed Services Committee and also sits on the powerful Energy and Commerce Committee.

“Guam has a military population of 23,000 and is going to grow with the military buildup, all the funding coming on in,” Rep. Moylan explained. “We need somebody as a delegate to have a voice in that committee. Otherwise, you’re just a visitor in someone else’s classroom.”

Interestingly, Guam also has a small ethnic Chinese population, around 2,000 people, less than 2% of the island’s total 170,000 strong population. The first Chinese and Taiwanese immigrated when the territory was still a Spanish colony, as far back as the 1600s. Today, Guam maintains a Chinese School and a large Chinese Chamber of Commerce.

“We have a lot of folks from China and Taiwan whose children are born in Guam and are U.S. citizens and have made Guam their home,” said Rep. Moylan. “Economically, they’re in a good position because there’s a lot of trade going on for the raw materials and for production of items. We can go to China from Guam to make whatever you want and then sell it on our shelves. They can speak the language, so it’s even better for them.”

How the U.S. came into its Pacific possessions

The U.S.’s position in the Pacific was first established in 1898 at the end of the Spanish-American War, fought to secure American economic interests in Asia.

John Hay, who was U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom at the time and later became Secretary of State called it “a splendid little war.” In the Treaty of Paris that ended the conflict, the U.S. compelled colonial landlord Spain to relinquish sovereignty of Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. Almost simultaneously, American businessmen in Hawaii overthrew the island chain’s indigenous government, further extending Washington’s reach.

Today, the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Office of Insular Affairs maintains Compacts of Free Association with the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau, and supports the territories of the Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The Freely Associated States, which are sovereign territories, give the U.S. military access to their land in return for aid, and the right of their citizens to travel to and work in the U.S. without a visa. They’re permitted to join the U.S. Military and have the right to U.S. Consular Assistance while traveling abroad, but are not entitled to U.S. passports.

American Samoa is the only U.S. territory without birthright citizenship, a condition it negotiated when its chiefs agreed to join the U.S. in 1900.

It’s counterintuitive, but many American Samoans oppose U.S. citizenship because they fear being federal subjects would deprive them of their customary rights, and enable mainland Americans to take ownership and dominate native lands, as has happened in Hawaii.

The arrangement means that while American Samoans are legally U.S. nationals, permitted to live and work anywhere in the U.S. and join the U.S. Military, they may not vote or run for office outside of the territory unless they formally apply for U.S. citizenship. It’s a controversial, semiautonomous status called fa’a Samoa, “the Samoan way,” that was recently upheld by the Supreme Court.

“Our territory’s government was unanimous in that case with the full backing of our people,” Rep. Amata of American Samoa told me via email, referring to the case that challenged the fa’a Samoa precedent.

But support for fa’a Samoa does not mean a lack of enthusiasm for the U.S. military: “The U.S. has full access to our strategic harbor and lengthy runway,” Rep. Amata said. “In fact, we would welcome and encourage more, such as stationing Coast Guard cutters here.”

The two Samoas

That sentiment differs in the western islands of the Samoan archipelago which also subscribes to fa’a-Samoa traditions, but which form the sovereign nation of Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa.

In May 2022, Chinese Foreign Minister Wáng Yì 王毅 visited the nation of Samoa during a tour of the region which included a stop in Fiji, where he and his counterparts in 10 Pacific Island nations — Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, Kiribati, Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, East Timor, Niue, and Vanuatu — could not agree on a sweeping security and trade deal. Samoa did however sign a bilateral agreement with China for “greater collaboration,” during Wang’s trip, citing China as a “key development partner” in infrastructure.

That came a year after Samoa’s Prime Minister Fiame Naomi Mata’afa decided to cancel a $128 million deal for a port that would have been developed by China. But even without the expensive new port, China owns 40% of Samoa’s foreign debt. And while Samoa’s largest trading partner is American Samoa, the country exports more goods to China than to the U.S. Mainland.

Nonetheless, Rep. Amata of American Samoa maintains a strong relationship with PM Mata’afa. “I am confident in her strong leadership, and I know that she is well aware of regional issues and has her people’s best interests in mind,” she said.

Rep. Amata also mentioned a letter the then-President of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) wrote, accusing China of inciting political warfare in his country. “China’s regional aspirations are clear to all, and the letter from former FSM President David Panuelo was an important warning for all of us in the Pacific Islands, and the U.S. must continue to show the necessary commitment in the region,” she said.

Military economies

The economies of America’s Pacific island territories are centered around military buildup. This year, the Marines opened Camp Blaz in Guam, moving 5,000 soldiers, equal to about 3% of the island’s population, from Okinawa to the new base. The relocation is largely in response to years of grievances about the Marines from their Japanese hosts, but it’s part of a larger buildup: Guam is also hosting a new $1.5 billion missile defense system, and the Department of Defense is planning to spend more than $11 billion on the island over the next five years.

Guam and American Samoa have some of the highest per capita military enlistment rates in the country (but neither territory has in-patient hospital services for veterans).

“China has their missiles directed at us. North Korea has their missiles directed at us. We of course, have to protect Ukraine also because they’re watching the end result of that war, right?” Rep. Moylan explained that, overall, civilians in Guam support the increase in military investment.

“If Russia keeps on advancing, and we don’t support the freedom of Ukraine, then that gives a greater feeling for Communist China to say, oh, weak America. We want Taiwan.”