Southeast Asia’s first high-speed railway opens in Indonesia after cost overruns and delays

Mostly funded by Beijing and built by Chinese engineers, Indonesia's first high-speed railway line opened on October 2. The first passengers were delighted, but there have also been controversies, and the project was completed several years late, and at a cost of $7.2 billion, more than a billion over budget.

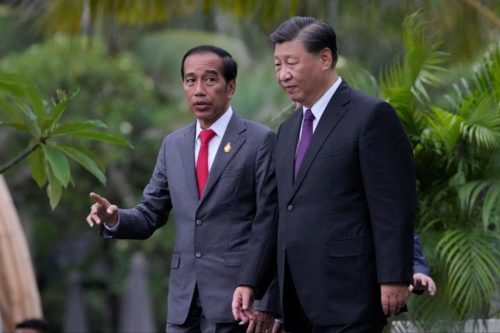

Indonesia’s President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo on Monday officiated the opening ceremony of the country’s high-speed railway connecting the capital Jakarta and Bandung in West Java.

A Chinese consortium took part in its financing and construction as part of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative to build transport, trade hubs, and infrastructure around the world. Indonesia is the world’s largest archipelagic nation of more than 275 million people and the target of several developmental diplomacy projects from Beijing.

Southeast Asia’s first high-speed railway links two provinces on Java Island — starting at Halim Station in East Jakarta and ending at Tegalluar Station in Bandung Regency — in around 45 minutes each way, which includes a stop at Padalarang Station in West Bandung Regency. The stations are not in the city centers.

“We will decide on the fare soon, but it will be more or less between 250 and 350 [thousand rupiah],” Jokowi told reporters on the launch day, referring to how each high-speed railway ticket will range from around $16 to $22.

“We are extending the free [trial period] until around the middle of the month.”

However, the launch was delayed several times for years, and the project overran its budget by more than a billion dollars.

I boarded the high-speed railway on September 28 during the initial trial period from the middle to late last month.

The trip was comfortable: It reached over 300 kilometers per hour (186.4 miles per hour) in around 10 minutes — with the speed meter hitting around 348 kilometers per hour (216.2 miles per hour) at one point — yet no major shake was felt, and no loud engine sound was heard.

Civil servants, families with children, and other members of the public took the ride on Thursday. The photographer for this story, who took a ride on Friday morning after being rescheduled due to high public enthusiasm, saw the meter reaching 350 kilometers per hour.

Puspa Ratih, who lives in East Jakarta, participated in the trial twice before doing it again Thursday for the first time with her family.

“The trip is also more comfortable than by [toll road] because it takes around two to three hours [to Bandung that way],” she told The China Project, referring to either getting on a minibus or driving to get there.

“[The ride] only took 30, 35 minutes — [and we] already got here [at Tegalluar Station]. The train’s interior is also nice.”

Irma Indrisari found going to the Halim Station from her South Tangerang residence near Jakarta was too far. Yet after the high-speed railway’s launch, she prefers to use the regular but slower train when traveling to Bandung because the former is “more expensive.”

She enjoyed her first ride regardless. “I am very impressed with the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway,” she told The China Project.

The high-speed railway — branded as Whoosh — has eight carriages that can accommodate 601 passengers on each train.

“Call this China’s infrastructure, bridge, or railway diplomacy — or whatever you will — but it’s ultimately a core thrust of Beijing’s soft power push abroad,” said Brian Wong, an assistant professor in philosophy at the University of Hong Kong (HKU) and a geopolitical strategist.

“Beijing can and is willing to engage in selective — somewhat limited nonetheless — skill transfer and knowledge dissemination in partner countries.”

How it started — and following controversies

Under a legal business entity named PT KCIC (Kereta Cepat Indonesia China) — translated as Indonesia China Fast Train — the company was established in October 2015 as a joint venture between a consortium of Chinese railroad companies through Beijing Yawan HSR Co. Ltd. and a consortium of Indonesian state-owned enterprises through PT Pilar Sinergi BUMN Indonesia — under a business-to-business scheme.

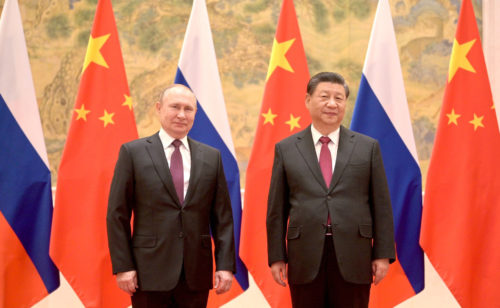

The location where the high-speed railway is set to operate is significant: China’s leader, 习近平 Xí Jìnpíng, first introduced the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative — which provided the “road” of the Belt and Road Initiative — during his state visit to Indonesia in 2013. A month earlier, he spoke of a “Silk Road Economic Belt” in Kazakhstan. (Counterintuitively, the “belt” is the land route, and the “road” is the sea route; the two concepts were then woven together by Communist Party wordsmiths into “One Belt, One Road,” or OBOR, but the preferred name is now Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI.)

China was not the only contender to build Whoosh. But after considering Chinese and Japanese bids, Indonesia’s government decided to award China the high-speed railway project because the People’s Republic did not require any Indonesian government financing or guarantees — unlike Japan’s proposal — among other considerations.

Trissia Wijaya, a senior research fellow at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto, Japan, said the Indonesian government chose China over Japan because authorities believed “China can finish [the high-speed railway] as timely as possible before 2019.”

“It’s more about politics because the Jokowi government wanted to maintain and keep the momentum in 2019,” she told The China Project.

“It’s also more about the business. At [that] time, Jokowi just came to power [in 2014] and his mindset was full of business-oriented strategies, like, who came with lucrative terms, such as business-to-business [scheme] that doesn’t involve state budget.”

The project kicked off under the leadership of Jokowi, who attended the groundbreaking ceremony in January 2016.

Jokowi first won a presidential election in 2014 before being reelected for the second term five years later. (The next election will be held in February 2024; Jokowi is constitutionally barred from running for the third time.)

Jokowi remains popular, but the high-speed railway project has also brought controversies. Lasarus, the head of Indonesia’s House of Representatives Commission V, (which is in charge of telecommunications and public works among other things) criticized the Indonesian government in April for not “being careful at the start, which gave China the courage to pressure us to ask for guarantees from the state budget.” He called for the government not to make the state budget the project collateral “because it will certainly pose a big risk to the sustainability of the state budget.”

This comes as Indonesia’s Vice State-Owned Enterprise Minister Kartika Wirjoatmodjo said in February that both countries agreed on a cost overrun of $1.2 billion while at that time negotiating loan terms from the China Development Bank — leading the overall costs to increase from $6 billion to $7.2 billion. Around 75% of the project costs were funded using a loan from the China Development Bank, while the rest were from the consortium.

Meanwhile, Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan — Indonesia’s Coordinating Minister for Maritime and Investment Affairs — said in April that the Chinese government set the high-speed railway debt interest at 3.4% after being negotiated, instead of 2% that Indonesia’s government wanted. However, he said in June that the debt negotiation already concluded — at over 2% — without giving the exact figure.

A feasibility study suggested that PT KCIC, the entity that runs Whoosh, could hit the break-even point only 38 years after the high-speed railway has been made commercial, and then only if one-way tickets were priced at 350,000 rupiah ($22.45) per passenger. The final high-speed railway ticket prices might be lower, meaning it could take longer than that to recover project costs.

Besides exceeding costs, the high-speed railway’s completion was also delayed due to COVID-19, and because of land acquisition and other issues. The project was initially set to launch in mid-2021; it was previously set to be completed in 2019.

More recently, its launch was rescheduled from June to September — and then to October 1 before being pushed back to October 2.

The Jakarta Post’s senior editor, Kornelius Purba, wrote in April that the Indonesian president “can only blame himself for the prolonged delay of the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed train project, and the huge cost overrun.”

“There were too many loopholes in the contract,” he said, “clearly because Indonesia was so ambitious to realize the mega project as soon as possible. So, do not blame China.”

“Now Indonesia must pay dearly for its ‘take it lightly’ attitude and the damage caused by our negligence in the contract negotiation will likely continue, even long after President Jokowi ends his second five-year term in October next year.”

Other problems emerged: Some West Java residents who lived near the railroad had their houses damaged; social impacts and environmental concerns were also reported.

Lack of transparency and other concerns

Trissia of Ritsumeikan University — who focuses on Chinese and Japanese infrastructure investments in Indonesia — said she was concerned over the extent of how far the Indonesian government would inject the state budget into the high-speed railway project.

“There is a lack of transparency here, especially in terms of financial arrangements between the Chinese consortium and Indonesian consortium — and also the relationship between the Indonesian government [and] their own state-owned enterprises,” she said.

Yet Trissia said it would be “too far” to think that Indonesia would fall into the so-called “debt trap diplomacy” regarding the high-speed railway.

“After all, our economy is performing well and the debt-to-equity ratio is quite good actually,” she added, referring to the country’s ability to pay off its high-speed railway debt.

According to the latest September 2023 volume of the External Debt Statistics of Indonesia, jointly produced by Indonesia’s Finance Ministry and central bank Bank Indonesia, “the structure of external debt in Indonesia remains sound, supported by prudential management.”

“External debt was still manageable in July 2023, as reflected by a lower ratio of external debt to gross domestic product (GDP) of 29.2% in the reporting period compared with 29.3% the month earlier, and dominated by long-term debt that accounted for 87.8% of the total,” according to the executive summary.

BRI’s future and the declining role of the U.S. in Southeast Asia

Harryanto Aryodiguno, an international relations lecturer at President University in West Java, said the high-speed railway would definitely boost Jakarta-Beijing ties.

“China has experience, so there is interdependence. Indonesia’s dependence on China is [it needs the country to] build infrastructure and skills,” he told The China Project, adding that China would depend on Indonesia to export its technology and related skills.

“[Jokowi’s] successor will continue to strengthen the relationship,” he said, “especially after the upcoming election.”

Meanwhile, Indonesia’s government would consider China as one of the potential parties to further expand the high-speed railway to Surabaya — the country’s second-largest city, in East Java Province — which is over 700 kilometers away from Jakarta.

Yet Harryanto believed Beijing’s main rival would need to step up its efforts in Indonesia and Southeast Asia.

“The United States will lose its role here,” he said.

“America [should have further] played its role so that America continues to believe it has influence in Southeast Asia, especially in Indonesia.”

Experts said the high-speed railway project would not significantly correlate with the Belt and Road Initiative’s reach in other Southeast Asian countries.

Wong of HKU said there was a “limited direct utility arising from the project for the rest of Southeast Asia, but reasonable utility for the Bandung-Jakarta stretch of land.”

“The key emphasis of the high-speed railway is very much on intranational — as opposed to international or regional transportation integration and interconnectivity,” Wong said.

One factor is the region’s geography: Indonesia is in Maritime Southeast Asia — unlike Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and beyond on mainland Southeast Asia.

“High-speed railway will be contributing to the regional economy if it’s located in a landlocked region,” Trissia said.

China’s domestic economic slowdown and decreasing labor productivity could cause another problem.

Trissia said, “I don’t think this project can be set as a benchmark to define whether it will attract investments or not.”

“Don’t forget about the fact that China is struggling [with its economy] now,” she added.

“The Chinese investors are busy with their domestic issues before they are trying to find new opportunities abroad.”

Policymakers in Beijing have been compelled to change their BRI strategies, given “the pretty lackluster returns over recent years from select countries to which Beijing has pumped billions of aid and loans, the pandemic, as well as domestic economic woes in China,” Wong told The China Project.

“China is keen to focus on and prioritize countries that are likely to generate positive dividends and returns to investment,” Wong said.

“Indonesia certainly counts amongst these economies, given its sizable population and heft in ASEAN.”