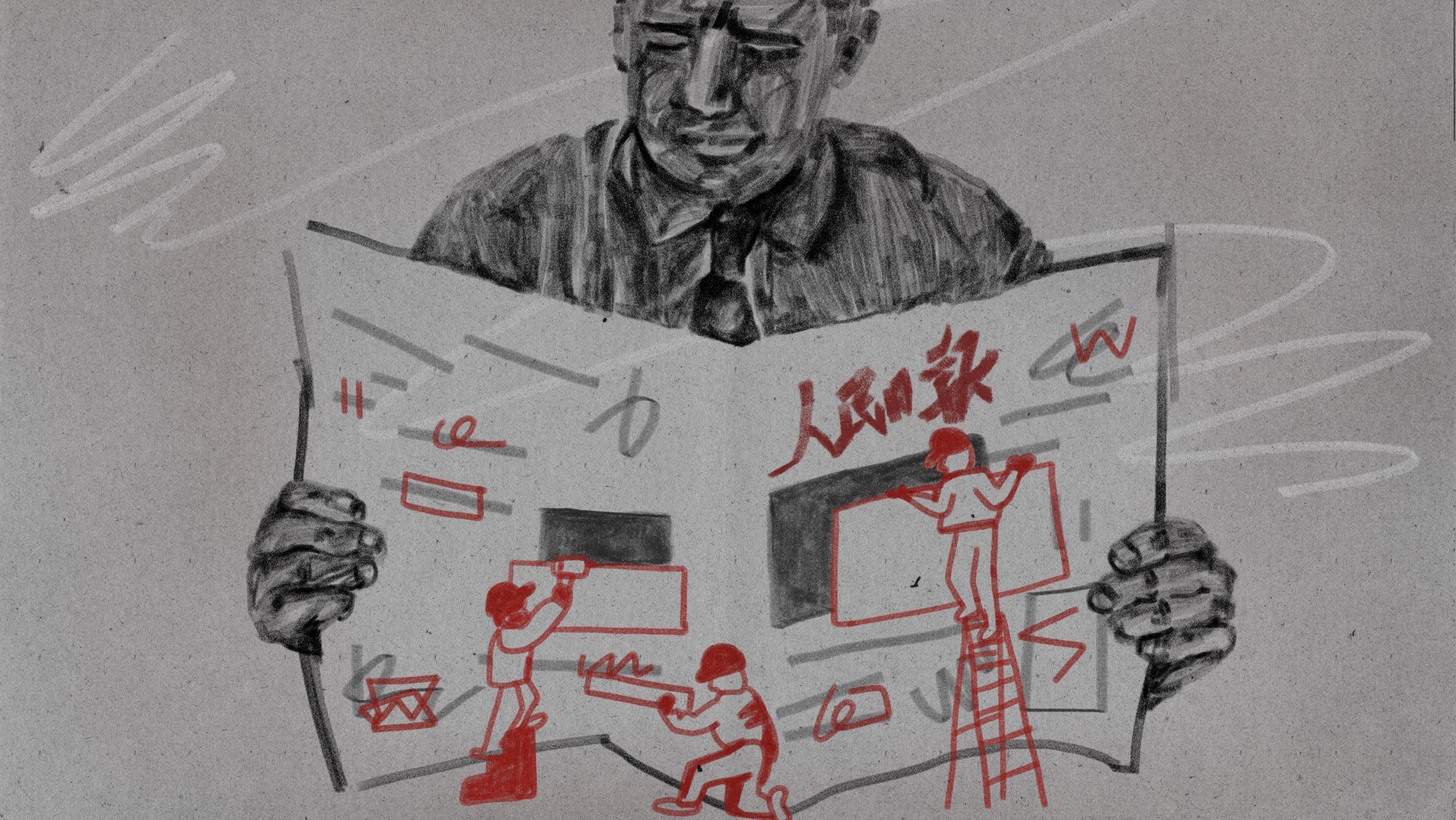

Chinese state media editorials, written by no one ever

What happens when you find your name attached to an editorial you didn’t write, expressing an opinion that isn’t yours?

Last month, an editorial carrying the byline of former New Zealand prime minister Jenny Shipley appeared on People’s Daily, the mouthpiece paper of the Chinese Communist Party, just as tensions were escalating between New Zealand and China following Wellington’s decision to ban Huawei products. “We should learn to listen to China,” the editorial said. “We need to work with China.”

Shipley received bitter criticism from domestic political opponents for complimenting China’s economic success, gender equality, and the Belt and Road Initiative.

But the People’s Daily editorial befuddled Shipley as well. She told the New Zealand Herald that she had not spoken to “China Daily” since December, and had not, in fact, written the February op-ed in People’s Daily. “It is important for the Foreign Minister and Prime Minister and others to understand that I would never think of getting into a public situation like this at such an important time for New Zealand’s relationship,” Shipley said.

As it turns out, People’s Daily put together the “editorial” from a past interview, and published it under Shipley’s name without her authorization — or awareness. The paper soon changed the byline from “By Dame Jenny Shipley” to “An interview with Dame Jenny Shipley”:

Shipley was not the first victim of this practice of journalistic malfeasance from Chinese media.

Peter Hessler, author of the acclaimed nonfiction River Town: Two Years on the Yangtze, was baffled to find himself praising China’s political model vis-à-vis Egypt’s — where he was based — in a 2015 China Daily editorial. He had indeed talked to a reporter from the publication in an interview, but the paper rearranged his quotes and published them in an “editorial” that made it seem like he wrote it.

“A reporter asked me to do an interview for China Daily,” Hessler recalled in an article for the New Yorker. “The paper then removed selected material from the interview, ran it under my byline, and made it appear that I had written an op-ed in support of the government. When I complained, the editors removed the article from the English-language Web site but refused to issue a retraction. In the end, I should have known better, because China Daily is notorious for pushing the regime’s agenda, but after dozens of interviews I had grown complacent.”

The same happened in 2012 to Australian scholar Rory Medcalf. Having talked to two journalists for an on-the-record interview, he was later surprised to find an editorial, published under his name, on the Global Times — a tabloid well known for its nationalistic views. While the article Medcalf supposedly wrote provided “a reasonably accurate rendering” of part of his opinion, some words — “Tibetans separatists,” for instance — were entirely not his; the “editorial” also willfully omitted the criticism of Chinese officials, which he had expressed in the interview.

While the Global Times later clarified and apologized for the mishandling of the interview, Medcalf pulled no punches in publicizing his discontent. “The fact remains that someone on the newspaper’s staff thought it was perfectly acceptable to put words into my mouth to suit the Communist Party line,” he wrote in a blog post.

At least that Global Times article did, though partially, reflect Medcalf’s views. When Harvard sinologist Roderick MacFarquhar, who passed away in February, attended a conference Beijing in 2015, he criticized Xi’s “Chinese dream” of not being “the intellectually coherent, robust and wide-ranging philosophy needed to stand up to Western ideas.”

But the Global Times apparently misheard, and rephrased MacFarquhar’s statement about the “Chinese dream” as one that would “make great contributions and exert a positive impact on human development.” The tabloid then apologized, saying it had translated the quote from a Chinese-language outlet, and removed the article from its website.

Thanks to the People’s Daily editorial, Jenny Shipley is now under further scrutiny over her connections to China. On March 4, she retired from the board of China Construction Bank (New Zealand), a subsidiary of the Chinese state-controlled corporation.

The lesson here? If you’ve ever been interviewed by Chinese state media, now would be a good time to search for your byline. There might be an article out there that you “wrote” without ever knowing it.