The future of the fight to preserve Uyghur culture

As the Chinese government crushes Uyghur culture in Xinjiang, Uyghurs abroad are making new efforts to preserve their traditions — but will they succeed? Some scholars say a revival is possible.

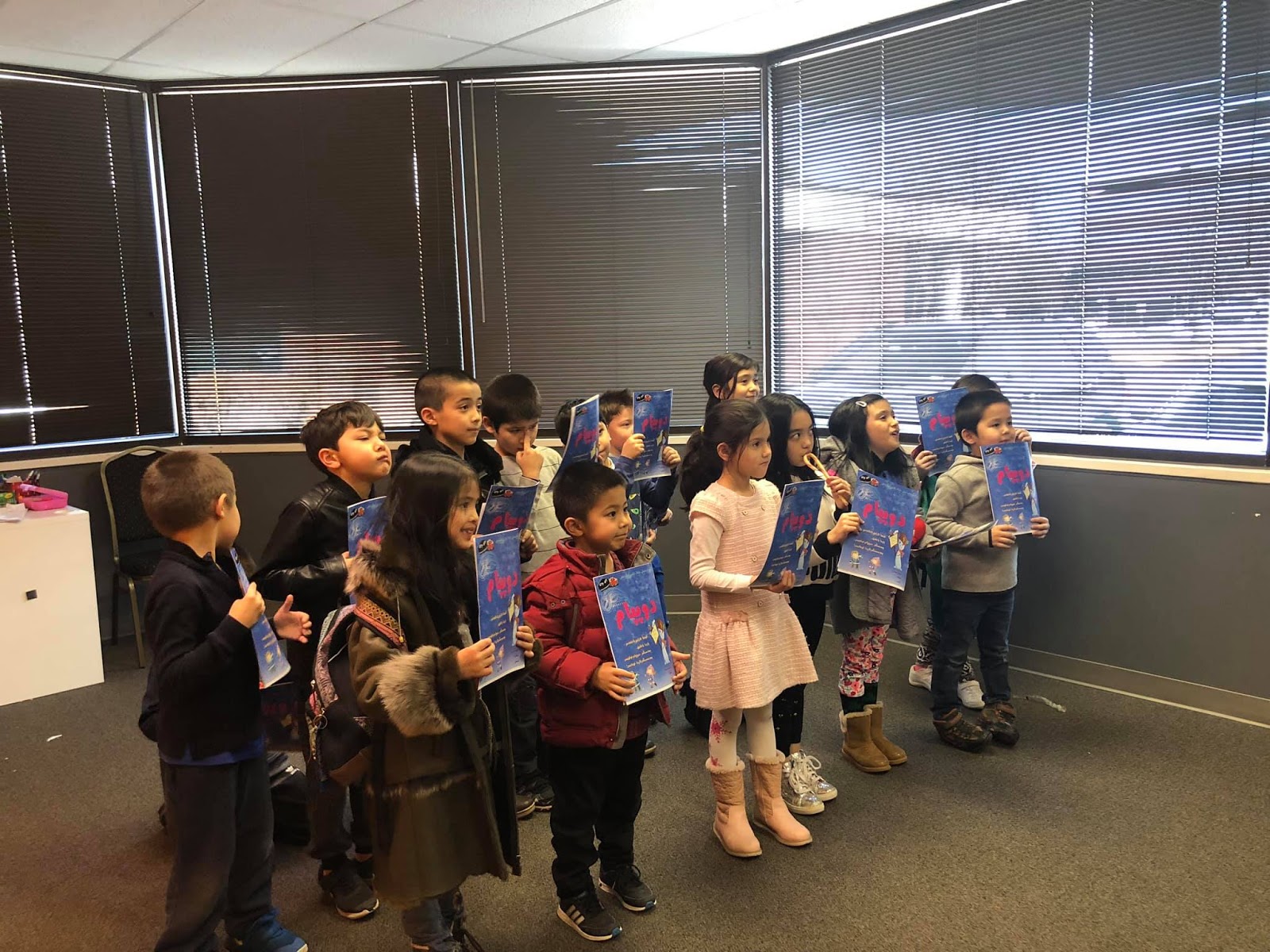

“Head, shoulders, knees and toes, knees and toes,” sang the kids gathered at an education center in Virginia, to the tune of the classic children’s song — except they were not doing so in English, but in Uyghur language. These are among the 60 Uyghur students — ages ranging from two to early 30s — who come to Ana Care & Education on Sundays to learn their mother tongue.

Marketing manager Irade Kashgary started the school in Fairfax, Virginia, with her mother, Sureyya, in February 2017. It is one of many projects by the Uyghur diaspora across the world fighting to keep the community’s customs and traditions alive amidst the Chinese government’s crackdown in Xinjiang.

Adrian Zenz, an independent researcher on China’s ethnic policies said last month that an estimated 1.5 million Uyghurs and other Muslims could be held in so-called re-education centers in the Xinjiang autonomous region in northwestern China, up from his earlier figure of 1 million.

There are approximately 400,000 Uyghurs residing outside China, especially in Central Asian countries, like Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan, as well as in Turkey.

In an attempt to push back against the Chinese government’s repression of their culture, members of the diaspora all over the world have been reasserting their identity, such as through Uyghur language classes, artistic endeavors, and eateries, among other forms. But how far can this form of identity preservation go?

“With the elders being locked up in concentration camps, our fear is that younger generations of Uyghurs will not want to identify as Uyghurs, or may not even have any connection to Uyghur culture,” said Kashgary. The 25-year-old moved to the United States two decades ago. “The hope is to keep it thriving in the diaspora, and maybe someday, to even have Uyghur recognized as a second language here.”

“With the elders being locked up in concentration camps, our fear is that younger generations of Uyghurs will not want to identify as Uyghurs, or may not even have any connection to Uyghur culture.” —Irade Kashgary, co-founder of Ana Care & Education

High school student Kunduz Ablimit, who is enrolled in Ana Care’s language class, said: “I think it’s very important that we get a stronger grasp of our culture at the same time that the Party tries to destroy our culture.”

The 17-year-old has written a collection of short fiction stories, titled We Are Uyghur, which are inspired by the ongoing crackdown in Xinjiang. He says it will be published later this year.

Uyghur language schools have also been set up in Australia and Turkey, among other countries outside China.

The Uyghur language is part of the Turkic family of languages, which comprises at least 35 documented languages spoken by ethno-linguistic communities spanning Eurasia — from Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and large parts of Asia. Xinjiang, where the majority of ethnic Uyghurs reside, became part of China when the Manchu-ruled Qing empire (1636–1912) conquered it in the eighteenth century, during its westward expansion that also included the annexation of Mongolia and Tibet.

Uyghurs identify as Muslims, but their religious practices differ noticeably from Muslims in the Middle East. For instance, Uyghur prayer often involves chanting, dancing, and music. Brightly colored costumes, strumming music, scents of melded spices, and steaming naan bread are among many distinct elements of Uyghur culture that differentiate it from not just the Han Chinese majority culture of China, but also other Muslim ethnic groups around the world.

Uyghurs abroad work to preserve cuisine, writing, and poetry

YANA Kebab Express in midtown Manhattan, New York City, found itself as an accidental ambassador of Uyghur culture and cuisine when it opened in 2017 — just as China was escalating its pressure on Muslim minorities while not explicitly admitting to locking up the Uyghurs.

“We are happy that we have a chance to present this culture, which is something I didn’t really think too much of when I started this out in the beginning. Now we have people coming every day asking about the food, where it is from, the history,” said its founder Kudret Yakup, 36. “I am myself trying to enhance my knowledge on these [topics] too.”

A Harvard-educated investment banker by training, Yakup returned to the United States from China in 2016, when he first started selling kebabs on the street. Cumin-spiced mutton and rice pilaf cooked with carrots and olive oil take the centerstage on YANA Kebab Express’ authentic platters. Yakup said: “I wasn’t interested in finding some Uyghur food and changing it to the taste of the American audience. I chose to make kebabs because it has a wide customer base. People already are familiar with it.”

“I think as long as we think our culture has value, and we do love this culture, and we know what it really means, I think as long as we have this in mind, we will never lose it,” he said.

Bahram Sintash, who was born in Xinjiang but now lives in Virginia with his family, has been building Uyghurism.com to preserve digital copies of the popular Uyghur journal Xinjiang Civilization.

The 36-year-old fitness instructor, whose father was detained by the authorities at a re-education camp about a year ago, said he grew up during a cultural renaissance which saw a revival of Uyghur literature, art, music, and television programs. Sintash is optimistic that the Uyghur identity will prevail despite the current crackdown — as it did during the Cultural Revolution, he said.

“I think it’s very important that we get a stronger grasp of our culture at the same time that the Party tries to destroy our culture.” —Kunduz Ablimit, a 17-year-old student at Ana Care & Education

“We have survived similar things in the past. I am optimistic because there are many Uyghur writers and intellectuals overseas who will persist in preserving Uyghur practices,” Sintash said. “This is a community that has had a long history. It’s not easy to force us to assimilate.”

In London, Uyghur academic Aziz Isa Elkun, 49, publishes poetry written in his mother tongue on his personal website. These pieces are also translated into English, so that he can “show how nice the Uyghur language is” to a larger audience. Elkun, who is actively involved in the global writers’ association PEN International, has been pushing for Uyghur language books to be digitized and made available via the British Library.

But is digitizing resources, or even getting inscribed into heritage lists — a number of Uyghur arts and cultural practices have made it onto the United Nation’s lists for intangible cultural heritage — the same as actually preserving culture in practice?

“That is why we still have to actively target our younger generation of Uyghurs and let them understand how beautiful Uyghur culture is. Otherwise they may start to boycott it,” said Elkun.

“I am very, very worried about the Uyghur cultural identity. But we’re not giving up.”

Will Uyghur identity actually see a revival?

While the crackdown in Xinjiang appears to be fuelling a revival of Uyghur culture and customs abroad, some observers are not optimistic.

Darren Byler, a scholar of Uyghur culture who lectures at the University of Washington’s anthropology department, sees the crackdown as the Chinese government’s attempt to eradicate all unique aspects of the Uyghur identity. “I am not hopeful that the identity will continue to survive. I think children of the future generations, especially, might lose touch with their Uyghur heritage or just see it as backward, or lacking,” he said.

On the other hand, Rachel Harris, who specializes in ethnomusicology at the University of London, feels hopeful that people living outside China will do what they can to preserve the culture. In October last year, Harris received a grant from the British Academy to revitalise a form of community gathering known as meshrep, which incorporates music, dance, drama, and acrobatics, among other arts. Meshrep is maintained by ethnic Uyghurs in southeast Kazakhstan.

“I don’t think it’s so easy to eliminate a national identity. There was a huge resurgence of interest in Uyghur culture, language and identity after the end of the Cultural Revolution, and even if the current policies continue for years, I expect the same thing would happen as soon as the policies relax,” she said.

“There was a huge resurgence of interest in Uyghur culture, language and identity after the end of the Cultural Revolution.” —Rachel Harris, University of London

Timothy Grose, who researches Uyghur ethno-national identity, said the violent, state-led dismantling of the pillars of Uyghur culture can adversely affect the Uyghur identity in the short term. “In the short term, few Uyghurs in Xinjiang will likely dare to express their ethno-national identity with these cultural markers,” he said.

But the Chinese Communist Party may be overestimating the long-term efficacy of its attempt to stifle Uyghur culture.

“If we look at other colonial endeavors, we see that ethnic consciousness is regularly activated or strengthened as a result of systematic oppression,” he said, citing the revival of Hindu nationalism in the 20th century as an example. “I, perhaps optimistically, don’t see the Uyghur case being an exception.”