Hong Kong and Taiwan both vote, in very different ways, with very different results

Voters in Hong Kong and Taiwan went to the polls over the weekend, but the circumstances couldn’t be more different. Beijing released a white paper that talked glowingly about “universal suffrage” as the goal in Hong Kong, but included caveats that make clear it does not see the natural progression of democracy in the city as being anything like Taiwan’s experience.

The gap between Hong Kong and Taiwan as exemplars of democratically run Chinese societies (broadly defined) grew wider over the past weekend. In Hong Kong, a largely ceremonial election took place for a new legislature stacked in favor of the pro-Beijing establishment, while in Taiwan, four questions related to government policy were decided by referendum.

The two polls’ only similarity was a low voter turnout: in Hong Kong, it was just under 30%; in Taiwan, it was just over 40%; both were around half of what had been achieved in their previous respective elections. Yet when it came to the diversity of issues debated, the choices presented to voters, and the hard-fought, narrowly decided outcomes, the two exercises in representative government could not have been more different.

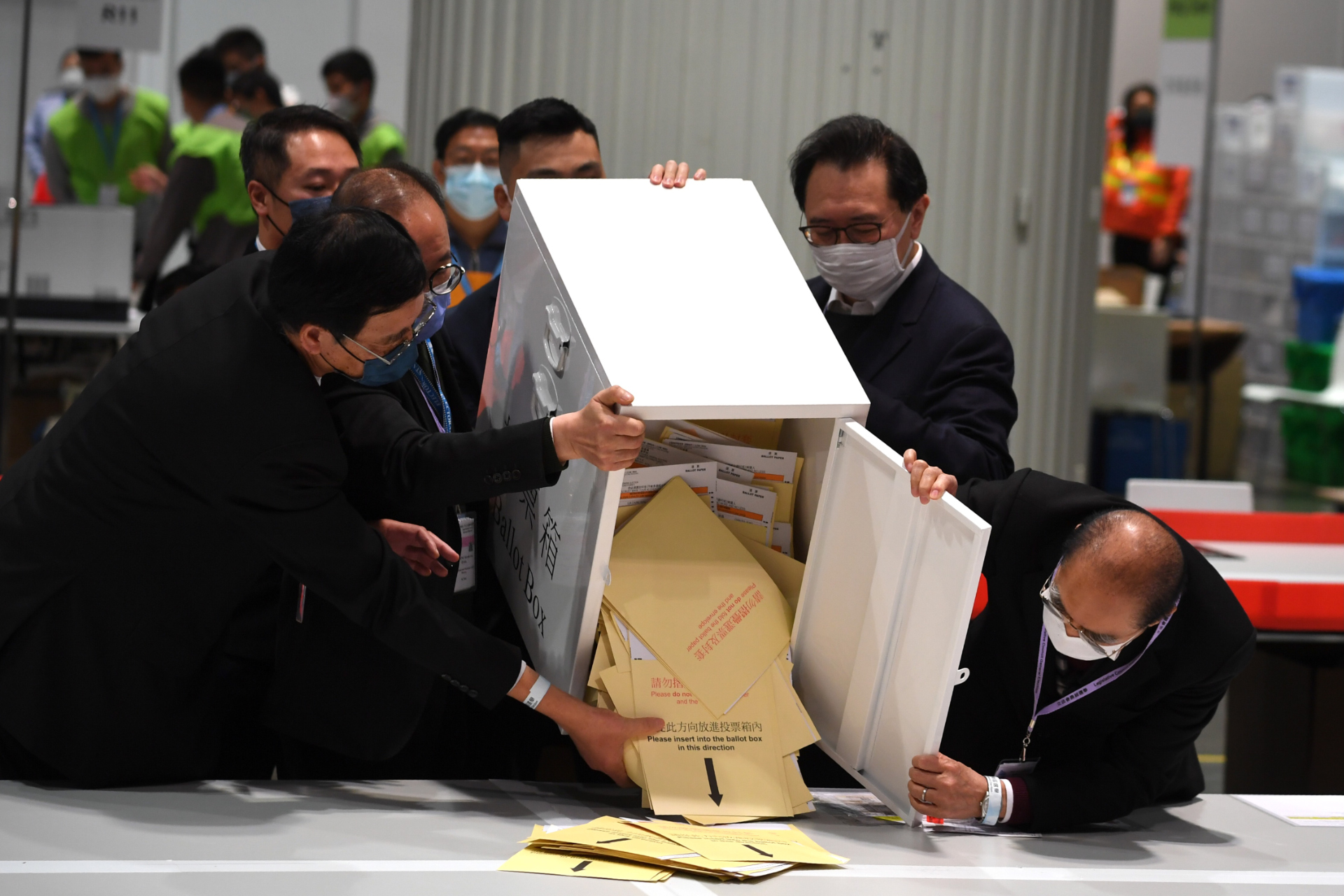

Hong Kong’s election had been billed by the government as an improvement of the city’s electoral system. This was despite a drastic reduction of the number of directly elected seats in its Legislative Council, or LegCo. Out of 90 in total, 40 were selected by a small group of electors known as the “Election Committee,” 30 came from “functional constituencies” supposedly representing various economic sectors, and just 20 were returned by all eligible voters according to where they lived. Even those few candidates standing in geographic constituencies had been sifted from a wider potential field by various pre-qualifying measures that had resulted in either the arrest, disqualification, or withdrawal of candidates that had not met the government’s definition of “patriots.”

In Taiwan, by contrast, the entire population, aged 20 and over, had been free to vote in the referendum. They had not needed to register because Taiwan’s household-registration system took care of that. They had not needed to be passport holders, let alone patriotic Taiwanese, because anyone who had racked up four months of residency was eligible.

Vanilla in Hong Kong

The issues up for debate could not have been more starkly contrasting in their substance — or lack thereof. In Hong Kong, despite valiant attempts by media outlets to sift through campaign pledges, it was hard to distinguish them. “Centrist” or “moderate” labels were tacked onto 11 candidates whose CVs did not fit the stereotype of being “pro-establishment,” but this made little difference to their chance of success. The winners, who were proclaimed almost entirely in landslides, had vastly superior resources from long-established pro-Beijing parties or were recently launched by wealthy and well-connected mainland-born businessmen.

It was hardly surprising, of course, that few of the contestants felt the need to try too hard once it became obvious that just about the only voters taking part would be those who had previously supported pro-establishment parties. Yet it was also hard not to sympathize with one candidate, Phoenix TV host Vie Tseng Chin-I (曾瀞漪 Zēng Jìngyī), who lamented her lack of advertising spend and grassroots organizational capabilities: “This [result] was nothing to do with the system,” she told an SCMP reporter.

Only one member of the formerly pro-democracy bloc scraped through. Tik Chi-yuen (狄志遠 Dí Zhìyuǎn) won a seat in a functional constituency, his fate decided by dozens, rather than tens of thousands, of voters. He did not opine on the relative merits of universal suffrage but was focused on social welfare issues.

Although a few candidates took potshots at Carrie Lam (林鄭月娥 Lín Zhèng Yuè’é), Hong Kong’s wildly unpopular chief executive, not one of them or their supposed rivals had anything but praise for the “improvement.” Similarly, nearly every voter turning up at the polls parroted a variation of the line that “order” and “safety” had been returned to Hong Kong by the new electoral process.

An anti-government crusade in Taiwan?

In Taiwan, meanwhile, the referendum was framed by its proponents as an openly anti-government crusade. The opposition Kuomintang, or KMT (which the Taipei Times refers to as the Chinese Nationalist Party), presented a “yes” vote on the measures as a way to rebuke a tyrannical ruling power, otherwise known as the Democratic Progressive Party. Yet it seems that voter fatigue with political grandstanding was only part of the reason for the lower turnout, down from 75% in Tsai Ing-wen’s (蔡英文 Cài Yīngwén) presidential election last year. Another reason was the issues were simply too detailed — or academic — to stir populist passions and command widespread public attention.

All four measures failed to pass, in an embarrassment to the KMT and a boost for the DPP in the final two years of the Tsai administration.

The most inflamed debate, which was voted down with the widest victory margin of around 400,000 votes, or less than 5%, was on the question of whether to restart a mothballed nuclear power project. A second question, equally vociferously debated by environmentalists on both sides, asked if construction of a much-needed LNG terminal should be halted and moved to a less ecologically sensitive part of the coastline. A third question challenged the electorate to decide whether imported American pork should carry a warning label against a dangerous ingredient or be banned outright, which might upset the country currently providing a nuclear deterrent against the other side of the Taiwan Strait. The fourth question was about referendums themselves: not whether they are a good idea, but whether they should go back to being held at the same time as other elections.

As the drop in turnout shows, these questions did not exactly get the average voter’s back up, let alone off the sofa. Indeed, the day after the referendum took place, most Taiwanese media were devoting far more space to Mandopop star Wang Leehom’s divorce. What these questions did do, however, is illustrate just how far Taiwan has matured, politically. The DPP, which 20 years ago was a pro-democracy, pro-environment upstart that had somehow managed to usurp a political behemoth not too dissimilar to the CCP, is today the responsible adult, a provider of measured responses and champion of longer-term economic planning.

Perhaps someone in Beijing might have anticipated the contrasting light that would be shed on Hong Kong and Taiwan by this weekend’s events. Although this seems unlikely, it might explain why the State Council Information Office released a “white paper” on Hong Kong’s democratic development, less than 24 hours after the polls closed. The paper is largely a rehash of past promises to eventually give Hong Kong the kind of democracy it was promised under the Basic Law. It talks glowingly about universal suffrage still being a goal worth pursuing. However, as always with these documents from Beijing, it includes caveats that make clear it does not see the natural progression of democracy in Hong Kong as being anything like Taiwan’s experience.

“The central government will continue to develop and improve democracy in Hong Kong in line with its realities…It will work with all social groups, sectors and stakeholders toward the ultimate goal of election by universal suffrage of the chief executive and all members of the Legislative Council,” the document says.

Fair enough. But then further down, the document says: “There is no single set of criteria for democracy and no single model of democracy that is universally acceptable. Democracy works only when it suits actual conditions and solves actual problems.”

Universal suffrage with Chinese characteristics? It remains to be seen what that might look like. What seems clear enough, though, is that Beijing knows what it doesn’t want for Hong Kong, which is what Taiwan has. As Mǎ Xiǎoguāng 马晓光, a spokesperson for the Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council, said last week in response to Taiwan’s invitation to the Democracy Summit hosted by the United States: “How can it be called democracy when the DPP authority is dividing Taiwan society for the personal interests of its party?”

Political analysts quoted by the South China Morning Post were certainly more sanguine about Beijing’s intentions with the white paper’s release. “All governments need their own narratives on key issues,” said Ray Yep Kin-man, of City University. “The document was also released to win the support of mainlanders.”

The coming weeks might bring more clarity on what the white paper really means about Hong Kong’s future democratic development. Carrie Lam is on her annual duty visit to Beijing. Could more surprises be in store for the next chief executive’s election, scheduled for March 27 next year, barely three months away? It will be known soon enough.