What the world needs to know about China’s outsize role in electric car future: Q&A with Henry Sanderson

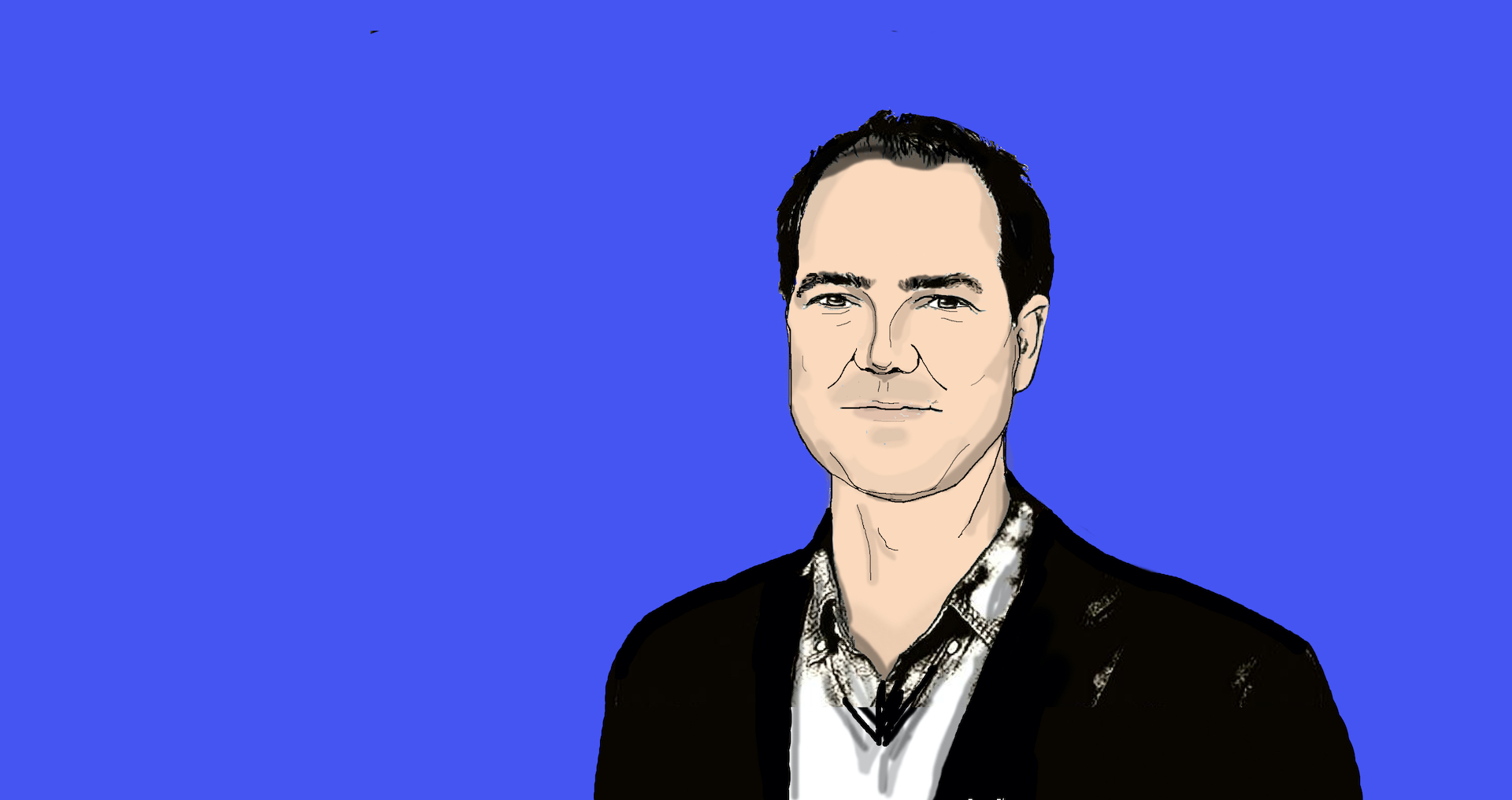

Henry Sanderson is one of the world’s leading experts on the geopolitics of electric vehicles and low carbon power. He told me all about China’s domination of the supply chains for the cars, the batteries that make them go, and what everyone needs to understand about the global race for EV dominance.

Henry Sanderson grew up in Hong Kong. He has covered business and finance in China for the Associated Press and Bloomberg. He now works as the executive editor for Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, a provider of data and analysis for the lithium-ion battery supply chain.

Henry has a unique understanding of the complexities of the electrical vehicle (EV) chain and China’s outsize role in it. He has just finished a book titled Volt Rush: The Winners and Losers in the Race to Go Green, which will be published this summer.

I called him to ask all about EVs and the supply chains that make them possible. We chatted by video call on June 10. This is an edited, abridged transcript of our conversation, part of my Invited to Tea series of interviews.

—Jeremy Goldkorn

You wrote a book with Mike Forsythe, on a very different subject from your new project, right?

While I was at Bloomberg, Michael Forsythe and I wrote a book about the China Development Bank and the whole model of Chinese state capitalism. It’s quite an interesting contrast because my newest book is much more about private, entrepreneurial companies. But when I was in China, when we wrote the book, we were looking at state-owned policy banks backing the system to secure oil and other things.

Whereas the difference now between the electric vehicles and the batteries is that it’s private companies doing it?

Yeah. It’s a fascinating story. A lot of these companies, their founders came out of the state sector, like the state lithium sector in Xinjiang or central China, which had gone bankrupt in the late 1990s. And then they founded these very entrepreneurial companies, that are incredibly fast-moving and have summoned lots of capital to invest in this supply chain, which has really made China a leader in electric vehicles and the supply chain. It’s the sheer amount of capital they can raise and invest that has made them leaders.

Can we set the scene in terms of the major players? I think everybody knows Elon Musk and Tesla, and people who have a little bit of awareness of the industry might know about XPeng, or NIO, or BYD. Who are the other players?

That’s why I wrote the book, which is, we’ve all heard of Elon Musk. We’re all aware that the electric vehicle revolution’s happening, there’s no turning back. But what’s going on behind the scenes? Who are the sort of hidden billionaires who control the supply chain?

We’re moving from a point of time where we took supply chains for granted, everything would be offshore to China and no one really thought about it, to now when we’re becoming much more aware of supply chains. We want both the products that we use to be clean and low carbon, but the supply chain too. And also, along with the carbon emissions of the supply chain, the geopolitics of supply chains are much more in the forefront.

The West has realized that China controls a lot of supply chains. In clean energy, also a lot of them are inefficient, with materials traveling from multiple countries.

So, my book looks at some of the players in the electric vehicle supply chains. While we know about Tesla, very few people might know that it depends on batteries from CATL, which is a Chinese company. In the space of 10 or so years, CATL has become the world’s biggest battery producer. And it counts for a huge share of the market. So, that’s one company.

And they’re all billionaires. They’ve created more billionaires than Google. It’s just an incredible sort of wealth generation that’s happened. And who would know where the lithium in your battery comes from, or the cobalt, or the nickel? And each of the production and refining of these minerals is mostly done by Chinese companies. Huayou Cobalt is another example, it went to the Congo, produces a lot of cobalt from there, and is now producing nickel from Indonesia.

So that’s another sort of company that people might not have heard of. Ganfeng Lithium, a big Chinese lithium producer, again, very entrepreneurial. It has invested heavily in Australia, Argentina. Tianqi Lithium, another one, bought a stake in Chile’s leading lithium producer, SQM.

There’s all these interesting developments going on behind the scenes that I felt people didn’t really understand. And they come with their own implications and geopolitics, and it’s an incredibly fast-moving space. We need to be more aware of these supply chains so we can understand what’s going on.

Can we talk a little bit about Robin Zeng (曾毓群 Zēng Yùqún) and CATL?

He is perhaps the most amazing example of a person and a company that seemed to come out of nowhere. I don’t think I’d even heard of the company five years ago. And now it seems that it’s basically making all the batteries for the world’s electric vehicles.

CATL is a fascinating story because actually it’s not as recent as people think. It came out of a company called ATL, which was founded in 1999. And it really tells the story of what happened in China, which is that both BYD and ATL started off making batteries for mobile phones and MP3 players. They took business away from Japan, which was the dominant producer at that time. And it was a classic case of southern China, lower labor cost, lower standards, and the combination of foreign investment into China at that period of time. They undercut the competition.

And the West was very happy for this business to be in China. It was cheaper. It lowered the cost significantly of iPhones and MP3 players. Then what we’ve seen is that both BYD and ATL, which later became CATL, they moved up the value chain. So, they were in a perfect position when electric vehicles came along. And exactly the time when electric vehicles were coming along, the Chinese government instituted a policy which basically banned South Korean and Japanese battery makers from the Chinese market.

So, you had this perfect combination. They had the background of making batteries, the Chinese government restricted their competitors, and at the same time as the Chinese government massively subsidized the purchase of EVs and development of EVs.

It was a classic case of creating domestic champions, but they also had had this experience lower down the value chain. And we can see BYD today, its market cap is over a trillion yuan. CATL is worth a trillion yuan. They are China’s green industrial barons — like the Rockefeller’s back in the day.

The question now really is that, having dominated the domestic Chinese markets, can these companies, like BYD, CATL, move into Western markets? And Western markets are very far behind. We have hardly any battery gigafactories [namely, factories that produce batteries for electric vehicles on a gigantic scale], hardly any lithium mines or lithium refining. Yet all our auto makers want to produce electric vehicles and our governments want to ban sales of internal combustion cars.

The question is for the West — we have the political will, the consumer demand, but are we going to catch up to these Chinese companies, which already make cost competitive batteries?

Take a popular battery chemistry now — LFP, lithium iron phosphate. No cobalt, no nickel, much cheaper. But China produces over 90% of these batteries. There’s almost nothing in the West. I think in the near term we’ve going to see the Chinese come and invest in Western markets, and we’re going to see the politics of that take a bit of a backseat.

And when you say, “Come into Western markets,” are you talking about the finished products, the vehicles themselves?

Yes, both the finished products as well as the whole supply chain — and then at the end the capacity to recycle batteries. China’s aim is to dominate the whole supply chain up to the electric vehicle, the highest value product, and sell those vehicles to Western markets. And we’re seeing that happen with a couple of companies like NIO going into Norway. Actually, MG, which was a British car company that was acquired by SAIC, Shanghai Automotive, sells electric vehicles here where I am in London — with a CATL battery. But while that’s the dream – creating a desirable Chinese brand abroad is going to be much harder than building a battery factory.

A Chinese company is making the black London cabs, the electric version as well now, right?

Absolutely. They make black electric cabs. It’s a Chinese company. And the only UK gigafactory is a Chinese company Envision. So, they’re coming into the European market and they’re going to the U.S. market as well. I’m pretty sure they will make moves into the U.S.

We’ll see high-level political posturing, like Boris Johnson when he came into 10 Downing Street, he said on the steps of Downing Street, “I want to make Britain a leader in battery technology.” And Biden, likewise, has a lot of talk.

But underneath, I think we’re gonna see the Chinese companies quietly going to Europe, going to America. Because we can’t decarbonize in the short-term without China. It’s gonna take time for the West to catch up.

It seems that China is already… Is it even possible for any other country to catch up with China’s lithium supply chain?

Yeah. It’s gonna be difficult. But the market is going to be so big there’s room for everyone. And we need more investment in lithium if electric vehicles are to succeed.

But China dominates a lot of the refining and processing. So even if a Western miner discovers and builds a mine in Africa they might have to send the lithium rock to China to be processed. I think the problem the West has is that we don’t have any of the sort of midstream refining processing capacity, which needs to be built. It’s often a dirty, sort of energy intense business. So, we need to build that. And in a green way. That’s going to take capital and investment.

But in certain sectors, the West has missed a real trick. Take the Democratic Republic of Congo, the world’s biggest producer. China’s bought up almost all the mining assets in Congo, and cobalt. The West has the biggest most professional mining companies in the world, but they all became so risk averse that they avoided the Congo. We see a bit more appetite returning to invest in Africa, but it’s gonna take time.

Finally in nickel, the Chinese have just made huge investments in Indonesia, which will become the dominant supplier of the metal for electric vehicle batteries. Indonesia has almost become like a nickel colony of China. It’s hard for me to see the west catching up.

Those are the three big ones, are they?

Yeah, so I’d say lithium, cobalt, nickel. And then in graphite for the anode, China produces almost all of the world’s graphite for batteries. So graphite will be hard to replace from China.

Where does it come from?

A lot of it comes from Shandong and Heilongjiang. A lot of it can be on small scales. It’s like the artisanal mining of China, but then you have synthetic graphite, which is artificially produced graphite. Most of that’s in Mongolia. It’s powered by coal. It’s incredibly environmentally unfriendly. And graphite is heavily tied to the oil industry – it uses coke produced from refineries. Most electric vehicle batteries use a blend of synthetic and natural graphite and we’re only really now paying attention and understanding the carbon footprints.

Electrical vehicles are supposed to be clean, but is that really the case? How dirty is the supply chain?

Studies show that overall EVs are greener. So, I’m not saying in this book that we shouldn’t transition to EVs, it’s all greenwashing, it’s all marketing. They are greener, even with a coal fired grid, and even with the supply chain we have at the moment.

But the point of my book is we need to clean up these supply chains. Because the whole solution to climate change is one of speed and scale, right? To make any difference to CO2 emissions, we need scale. And scaling the current supply chains will mean more emissions. Producing batteries is hugely energy intensive, as is graphite, as I’ve mentioned. Lithium is dug up by diesel trucks and shipped around the world.

Many automakers have pledged to get to net zero emissions, and they’re not going to do it without cleaning up this supply chain.

Are there technologies that can clean it up? Is it just a question of implementing them and maybe it’s expensive and difficult, or is this also going to require new tech, innovation to actually figure out how to clean it up?

No, there’s technologies available and coming that should clean up this supply chain. And what the West is trying to do is, try to build a clean supply chain from scratch. So, can we make these batteries using 100% renewable energy? They’re trying to do that in Sweden. Can we build a lithium refinery using 100% renewable energy? Can we use more recycled materials?

We’re seeing now the Chinese companies are also responding to their clients and are building renewable energy, and we’re seeing graphite producers in China move to Sichuan or Yunnan where there’s hydropower.

So, you can clean up, and it’s a process that’s really underway at the moment. You don’t need to reinvent the wheel. You just need renewable energy to power a lot of these processes. And then on the mining side, you need electric mining trucks. You need renewable energy to power the mines. There are processes and technologies underway to clean up the supply chain. That’s where we’re gonna see a lot of investment going.

In China and elsewhere?

Yeah, both in China and elsewhere. And this is the key problem for the West, is that policymakers in the EU, in the U.S., they’ve said, “We’re gonna build a clean supply chain. It’s not like China. It’s all dirty in China. ” But we’ve been waiting around too long. Time’s run out and the Chinese companies are not dumb. They realize they need to clean it up and they’re rapidly doing that.

But the problem is places like Indonesia where coal accounts for 60% of its electricity supply. How do you move away from coal? All these Chinese companies investing in Indonesia for nickel, we run a real risk of having a very high CO2 nickel in our electric car. So, that’s something that’s going to take longer, but we need to see that supply chain green up.

Because it’s also part of Xi Jinping’s signature One Belt One Road. What kind of legacy will that project have if it’s too environmentally destructive? What does China want to stand for when it invests in these countries?

There was this news this week, it’s not related to electric vehicles, but some coal-fired power plants in Zimbabwe that were supposed to be renovated by China, the projects were stopped because the new policy is no more coal outside of China.

That’s right. Xi Jinping’s issued this policy, which is a big challenge for some of these Indonesian projects. As far as I’m aware, there’ve been some loopholes where some of these Indonesian can captive coal-fired plants to power the nickel processing. It’s hard to move to renewables because you need a huge amount of energy to separate the nickel from the ore. The nickel is less than 2% of the rock that you are mining.

Two percent of the rock, huh? Wow.

It’s a tiny amount. So, you’ve got huge amounts of waste material. Where do you put that in the tropics, in an area prone to earthquakes? It could be an environmental disaster if it’s not sorted out.

Would you say there is a sense of awareness in the West of how far behind we are? Because in my impression, sometimes, especially living in America now, I really feel that people have no clue what is going on in the rest of the world.

I mean, even U.S. Secretary of State Blinken gave this China strategy speech, which I thought was a complete nothingburger. One of the things that really stood out to me was he said, “The American worker is the finest worker in the world.” And I was like, have you been to China? I have the sense that people are completely asleep. Not just the work ethic… Maybe Elon Musk isn’t, but…

I think you’re right. Elon Musk and Tesla know that China’s a big part of the issue but I think most people have no idea of what’s going on behind the scenes, and the speed at which these Chinese companies are moving, and the sheer amount of capital that we’re seeing on a weekly basis, billions of dollars being invested in this sector by Chinese companies.

And I think the problem is, in a way, Tesla dominates the West, right? And Tesla is an amazing success story. I think, in a way, that’s made people a bit complacent. That actually is not the whole story. But I think there are countries where people are worried like Germany.

The auto industry is a bedrock of Germany, it’s like post postwar, economic development. And there is real fear there that, wait a second, we’ve gotta make this transition, but we’re gonna lose thousands of jobs if we don’t capture the value chain? And the battery, electric vehicles are batteries on wheels. It’s one of the highest value components. If Germany can’t capture that, they will lose a lot of the value. And I say in my book, it is ironic that CATL was one of the first companies to build a gigafactory in Germany, in the heart of the heart of this country that was built on the auto industry.

Britain’s also very, very worried about it. Because we risk losing our auto industry. We also can’t export to the EU under the deal we’ve struck unless we produce a certain percent of components in Britain.

Can the West catch up?

We’ve seen some really interesting examples. One company I write about is called Northvolt in Sweden. They’ve succeeded in getting a lot of capital invested to build a battery factory to start building a supply chain in Europe. They’re planning to build a lithium refinery in Portugal. I think they’re a real success story for the West. They’ve channeled a lot of money, which is what’s needed. They’re using renewable energy, which is going to make it cleaner and greener.

There is real hope with companies like that, that the West can catch up. And we’re seeing examples in the U.S. too, with Redwood Materials, set up by the Tesla co-founder . The people at Tesla, to their credit, understand the sort of investment that is needed. And they are working on setting up big recycling facilities in the U.S., and also moving into producing battery materials. But again, Elon Musk is someone who can raise a lot of money, channel a lot of capital into something that can be done.

Right.

Yeah. So, in my book, I’m hopeful that we’ve begun the process, but I don’t think there’s time in the near term not to rely on China.

I could ask you all day about this… Aside from electric bikes and cars, which obviously have quite mature technology, what are we seeing in terms of flying boats and planes and other vehicles?

So, we’re seeing electric boats, a lot of movement in that area. And by that, I mean like electric ferries, things like that. We’re seeing more electric trucks, the trucking fleet also has to be decarbonized, a bit of movement there. We’re seeing short haul planes perhaps using batteries or some combination of batteries and something else.

For longer-haul trucking, [the answer might be] might be hydrogen fuel cells which we’ve seen China supporting quite a big way. I’ll gather details, but some Chinese trucking companies have come out. Hydrogen fuel cells may be a solution for longer haul trucking. Because you couldn’t have such a big battery. It’d take away from the cargo you could carry and would need so much electricity to charge.

But in terms of longer-haul flights, we’re not there yet.

The potential of electrification is limitless – we’re seeing electric bikes, electric boats, electric forklift trucks, electric pickup trucks. There’s more of a question around longer distance trucking, whether batteries can power such big trucks. And in short-haul aviation batteries could be a real possibility. New battery chemistries could also increase energy density and open up new avenues.

Last question: What should the consumer think about when they think about electric cars? If you want to be an ethical user of motorized transport, what should you think about?

I think we can use this transition to adjust some of our behavior. We don’t need to have electric SUVs. We should think about what kind of transport system we need and at the same time, where can we reduce inefficiencies? I don’t think it’s a question of moving from big SUVs to electric SUVs because that all takes bigger batteries, more materials.

I think we could learn a lot from China. One of the best-selling EVs is this tiny Wuling Mini. For a lot of city travel, you don’t need big cars, you don’t need big batteries. So, as a consumer, you should think about what we need.

Do you want to have a huge, massive battery sitting outside your house when you’re only driving 20 miles, wherever, within a city? As the charging infrastructure increases, we have more confidence in charging. We don’t need to have such big batteries and such, so much range. That’s another thing that I think range anxiety has been overblown, that everyone’s worried about range. I think you’ve got plenty of range for any city driving.

Then longer trips, you just need to have a fast charging option for an EV. So two questions consumers should ask themselves are: A: do I need a personal vehicle? We could move to more shared transport. B: Do I need bigger electric SUVs?

Unfortunately, those messages will not go down very well in places like Tennessee, where I live!

Yeah. Precisely. I address this in my book. I am realistic that personal transportation is not something we can just eliminate. There are a lot of people arguing that we shouldn’t just move to EVs, we should move to public transport.

We do need better public transport, but I think it’s naive to expect a family with young kids, like I have, wouldn’t want a car, doesn’t need a car. It’s incredibly useful, right? If we are too over optimistic about changing the system, the system won’t change at all.

We need to change. We need to transform now. But as a consumer, I’d say, think about what power you have to make an ethical choice within the constraints of our system.

What else should we think about?

Yeah, the number one thing is that there’s this idea that clean energy is somehow detached and going to solve all our problems, that it’s something new. But we’re actually going to rely on digging up more materials than we have in the past.

We’re moving away from oil, but we’re going to have greater reliance on mining, on raw materials than we had in the past. And I think that’s what people don’t realize. In the book, I talk about copper as well, which we can’t electrify without copper, right?

I’d say mining’s probably one of the unsexiest industries out there, but we need a big expansion of it to go green.

We need an expansion of it and also, cleaning up?

Cleaning up. Yeah.

So, well, my message to consumers is you may not know but your electric car’s got everything in it. It’s got geopolitics, it’s got potential child labor. It’s got all these issues that need to be cleaned up.

Invited to Tea with Jeremy Goldkorn is a weekly interview series. Previously: