China’s real but gradual progress in developing its own jet engines

They’re still new, and the process of installing them on Chinese aircraft is still ongoing, but China is now manufacturing the ‘hearts’ of jet aircraft and gradually reducing the dependence on Russian engines.

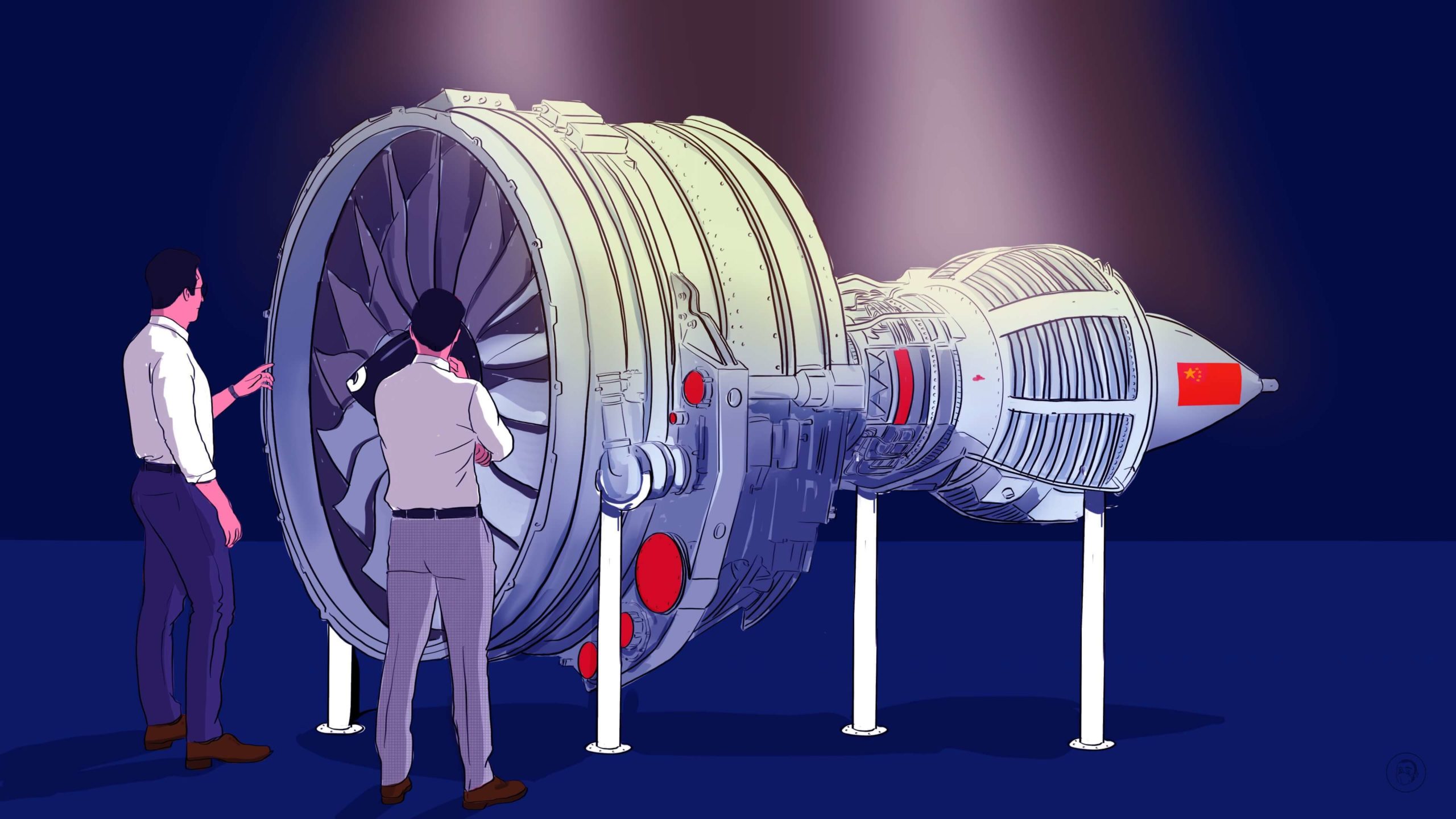

China has been famously reliant on imported jet engines, but perhaps not for too much longer. At this year’s Zhuhai Airshow that took place last week, there were several Chinese engines on display alongside those from foreign manufacturers such as CFM International, Pratt and Whitney, GE Aviation, and Rolls-Royce.

China’s new jet engines

The most prominent Chinese jet engine developer is Aero Engine Corporation of China (AECC), a company that was first established in 2016.

AECC’s engines have been prominently displayed at Zhuhai airshows going back to 2018. This year, the company’s exhibit included five different engines, including the WS-10 Taihang, which is China’s first high-thrust turbofan engine with an afterburner. There was also a new kind of WS-10 equipped with a 2D-thrust vectoring control nozzle, which provides fighter jets with enhanced maneuverability and stealth capabilities.

These Taihang engines are now powering China’s latest fighter jets: the Chengdu J-20 Mighty Dragon and the Chengdu J-10 Vigorous Dragon. AECC’s display of a turbofan engine with a 2D-thrust vectoring control nozzle was particularly noteworthy at this year’s airshow, as it shows that China is closing the technology gap between the capabilities of its latest J-20 stealth fighter — with its Chinese engine — and the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor.

Furthermore, the WS-10 engine is a precursor to a new generation of jet engines, the WS-15 turbofan engine. The WS-15 was not on display at this year’s airshow, but in March, the Global Times reported that the WS-15 is undergoing testing and will be installed in the J-20 stealth fighter in the near future, which will allow the J-20 to finally take its “ultimate form.” The WS-15 has a low bypass ratio (i.e., the ratio of the flow rate of the bypass stream and that entering the engine core), which is more efficient at higher speeds, and is capable of thrust vector control (the ability of the aircraft to manipulate the direction of the thrust from its engine) with a thrust of 15–18 tons.

Then there is the WS-20, also not displayed at this year’s airshow, a high-bypass turbofan engine that is also still undergoing testing, but is intended to power the Y-20 Kunpeng large transport plane. The WS-20 is apparently still in the experimental phase, however. Although Y-20s have been photographed in the past equipped with this engine, at this year’s airshow, the participating Y-20s were not powered by the WS-20.

Along with the WS-10 variants, at the airshow, AECC also had some of its newest engines on display for the first time, but there is very little public information about them available as yet.

- The AEF1300: A dual-rotor turbofan engine with high thrust, a high bypass ratio, and low fuel consumption.

- The CJ2000: A turbofan engine with low maintenance cost and low fuel consumption, intended for airliners.

- A series of engines intended for civilian aircraft: the AES100 turboshaft, the AEP100 turboprop, and the AEF100 turbofan engines.

The narrowing gap

Spectators at the 2002 edition of the Zhuhai Airshow got to see what was described as “the first jet engine to be designed, manufactured, and tested entirely in China,” the WP-14 Kunlun. The WP-14 took 20 years to develop, and was fitted to later variants of Chinese fighter jets developed from older Russian jets, the Chengdu J-7 and the Shenyang J-8. The WP-14 was not considered state-of-the-art by any means, but it was touted as a major achievement for China’s aircraft engine program.

Another major milestone occurred in 2021 when two J-20 fighter jets equipped with Chinese-made WS-10 engines flew at that year’s Zhuhai Airshow. Chinese military commentators said that this marked the end of China’s dependence on imported engines. In March 2022, CCTV ran an interview with the head of the Manufacturing Technology Institute at the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC), China’s massive state-owned aerospace and defense conglomerate, who stated that China has now mastered the ability to independently develop jet engines, which he called the “hearts” of military aircraft. Around the same time, the chief editor of the magazine Aerospace Knowledge told the Global Times that China has now closed the gap with the U.S. on jet engines from 20–30 years to 10–15 years.

Russian addiction

But China still has a long way to go to wean itself off Russian jet engines. According to one estimate, at least 40% of the engines of China’s fighter jets still depend in part or in full on Russian engines and parts. By this estimate, from 1992 to 2019, Russia provided China with around 4,000 engines for helicopters and military aircraft, and with the sanctions imposed on Russia by Western countries, China’s lingering dependency on Russian engines is now placing the acquisition and servicing of Russian engines at risk.

It was only really in 2016 that China started to devote large investments to promoting its jet engine development program, in particular with the establishment in that year of the Aero Engine Corporation of China (AECC). As outlined above, AECC is now starting to produce the goods, but the use of Chinese engines in fighter jets and other aircraft is still a gradual process, and China will remain hitched to Russian engines for some time to come.

The new C919 commercial passenger jet built by Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (COMAC), which has now been cleared for use by China’s airlines, is a case in point. The plane still makes use of the LEAP engine produced by the France-U.S. joint venture CFM International. China is developing its own engine for the C919, the CJ-1000A Changjiang (长江), a version of which was first unveiled at the 2012 Zhuhai Airshow, but this engine has not yet been certified, and may only start to power the C919 by 2025 at the earliest.

The full installation of China’s own jet engines is not going to be easy or quick. As one foreign observer put it, making jet engines is “more art than science,” and the leading Western manufacturers have “tacit knowledge” that their Chinese competitors are still lacking. Indeed, China’s jet engine development program is literally a young industry, with many of the country’s scientists, engineers, and designers working on jet engine development still in their late twenties and early thirties.

But these people have time on their side. On Monday, the newspaper China Youth Daily, appropriately, ran a lengthy article on a group of scientists researching titanium alloy engines at the Institute of Metal Research at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. This group is indeed very young, but very determined to make China’s planes fly with Chinese engines.