The Belt and Road: China’s ‘project of the century’

A short explainer on the history and planned development of Xi Jinping’s signature initiative — to put China at the center of a global network of transport, commerce, and infrastructure.

Quick facts on China’s Belt and Road

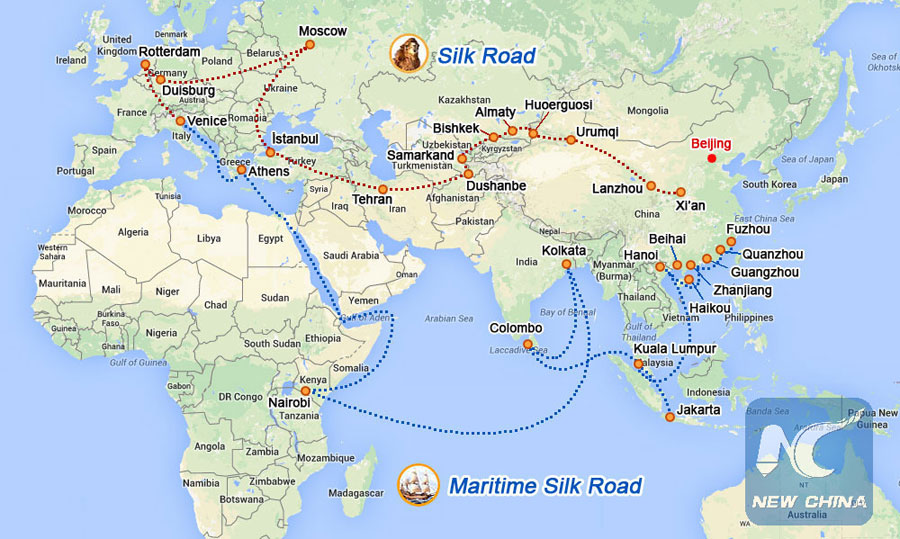

- Belt and Road is basically a network of railroads, highways, gas and oil pipelines, and ports across Asia and beyond.

- President Xi Jinping first proposed Belt and Road as the “Silk Road Economic Belt with Central Asian Countries” during a visit to Kazakhstan in 2013.

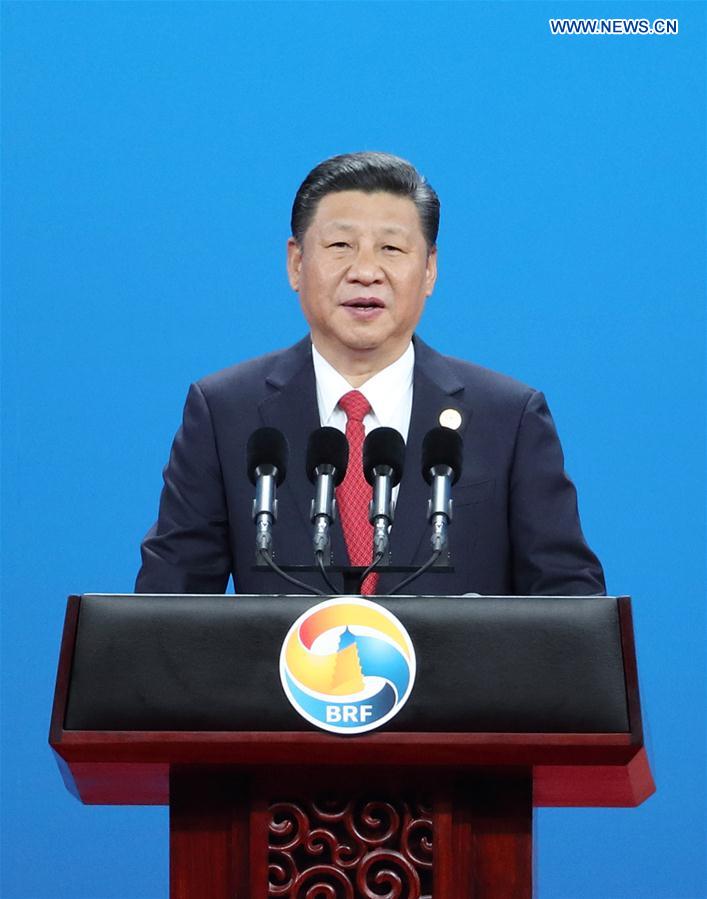

- The project name later changed to the “Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road,” or “One Belt, One Road,” abbreviated to OBOR. By the time of the Belt and Road Forum of May 2017, Chinese official statements were calling it the “Belt and Road Initiative,” or BRI.

- Belt and Road comprises two economic chains: a land route, stretching across Western China, Central Asia, and into Europe, as well as a maritime route, which flows along China’s eastern coast, threads through Southeast Asia, then turns to Africa and wraps up in Europe.

- The project has received pledges of more than $1 trillion in infrastructure investments across more than 60 countries, with China recently committing $124 billion in funding.

- Belt and Road has signed on 65 countries as of 2016, with 28 heads of state attending China’s summit in May.

China’s new leader makes a defining announcement

On September 7, 2013, Xi Jinping took the stage inside a wood-paneled lecture hall at Nazarbayev University in Astana, Kazakhstan. Earlier in the week, the new Chinese president — who was selected to become leader of the Communist Party of China in November 2012, and assumed the role as head of state in March 2013 — had attended his first Group of 20 summit in St. Petersburg, Russia. There, in his opening speech, he proudly declared China’s mission to expand the global market and create more development opportunities in other countries.

In Kazakhstan, speaking in front of government officials, university faculty, and students, President Xi returned to his pledge of greater economic engagement, emphasizing stronger trade ties and regional cooperation to reach shared economic and development goals. To that end, he announced ambitions to revive the ancient Silk Road, on which merchants thousands of years ago transported silk, porcelain, and jade from China to Europe by way of Central Asia. “I can almost hear the ring of the camel bells and [see] the wisps of smoke in the desert,” he said. He was just as clear about what his objectives were not. “China will never seek a dominant role in regional affairs, nor try to nurture a sphere of influence.”

The announcement officially kicked off China’s Belt and Road Initiative, a sprawling network of railroads, highways, gas and oil pipelines, and ports that aims to trace the channels of the ancient Silk Road route.

China moves to assert leadership

Also known as One Belt, One Road (OBOR), the effort has drawn commitments from over 60 countries and international organizations, and has been described as China’s “project of the century” — many would go so far as to call it the most important initiative in 21st-century global trade, particularly now that Donald Trump has pulled the U.S. out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership — and its most important foreign policy under President Xi. Significantly, the initiative marks a bold separation from the self-contained course set by former Party leader Deng Xiaoping in the early 1990s, famously summarized in a phrase he used (韬光养晦 tāoguāng yǎnghuì), meaning to “hide our capabilities, bide our time,” and wait for a later moment for China to assert leadership.

In line with Xi Jinping’s vision to “rejuvenate” China and return it to its historical place of prominence in the world, Belt and Road has become a core piece of his legacy, and the success of its execution is widely viewed as a referendum on his leadership.

The massive undertaking is divided into two main components: the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road. The “Belt” is a series of overland routes that will collectively connect China with Western Europe through the resource-rich countries of Central Asia. The “Road,” counterintuitively, refers to a dizzying sea route that flows around Southeast and South Asia, through Africa, and into the Mediterranean.

Beyond the rhetoric, the true motivations behind China’s designs have been widely speculated upon. Government officials, analysts, and academics say factors driving the initiative include the search for new markets to sell Chinese goods, the need to unload the country’s excess steel production, and the desire to promote economic development to quell tensions in the country’s Western region.

Financing China’s grand plan has involved extensive negotiations with many of the partner countries tied to the project. Most observers agree that the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), established in part to secure and bolster financing for Belt and Road, has stuck its landing in the international community. With investments in nine projects across Europe, Asia, and the Middle East in its first year, AIIB is viewed as advancing Belt and Road’s agenda with discipline.

One of the central debates that continues to hang over Belt and Road is the extent of its intentions to reshape the world’s geopolitical power structure. Drawing frequent comparisons with America’s Marshall Plan from the post–World War II era, Belt and Road’s vast ambitions and potential has been received with skepticism and mistrust from some parts of the world, while sparking controversy and backlash in others. The U.S., in particular, appears unsure of where to position itself, an ongoing uncertainty that may come as a detriment to itself and the global order.

A global good or neocolonialism?

Will President Xi succeed in realizing his vision for a revival of ancient trade routes and new, China-led global connectivity? What will Belt and Road mean for Asia and the world? Check out these perspectives for more:

- The China Project’s Kaiser Kuo argues that Belt and Road may be crucial to peace in the 21st century, as it promises to provide a number of necessary global public goods. He cautions that Americans should “stop sneering” at the plan, and notes that comparisons with the more politically motivated Marshall Plan come almost exclusively from the West.

- Skepticism about the plan’s execution and purported advantages are not confined to the West: Even Chinese firms appear to be cautious of the political risks taken on by the project’s ambition.

- China’s motives in pushing the project upon the world are a mix of economics, geostrategy, and philosophy.

- The South China Morning Post provides an interactive portrait of five key projects.

Latest Belt and Road news from The China Project (plus fun propaganda videos!):

- June 6, 2017: Xi Jinping on the Bright Road to Kazakhstan

- June 2, 2017: The China-Arab Expo

- May 17, 2017: Belt and Road protests

- May 16, 2017: China’s plan for Pakistan

- May 15, 2017: A Belt and Road rap song

- May 12, 2017: China’s Belt and Road: Coming soon to a theater near you

- May 11, 2017: No respite from cringeworthy propaganda — OBOR is coming to town

- May 9, 2017: A bedtime story about massive infrastructure projects