China’s fishing in South American waters raises questions, fears

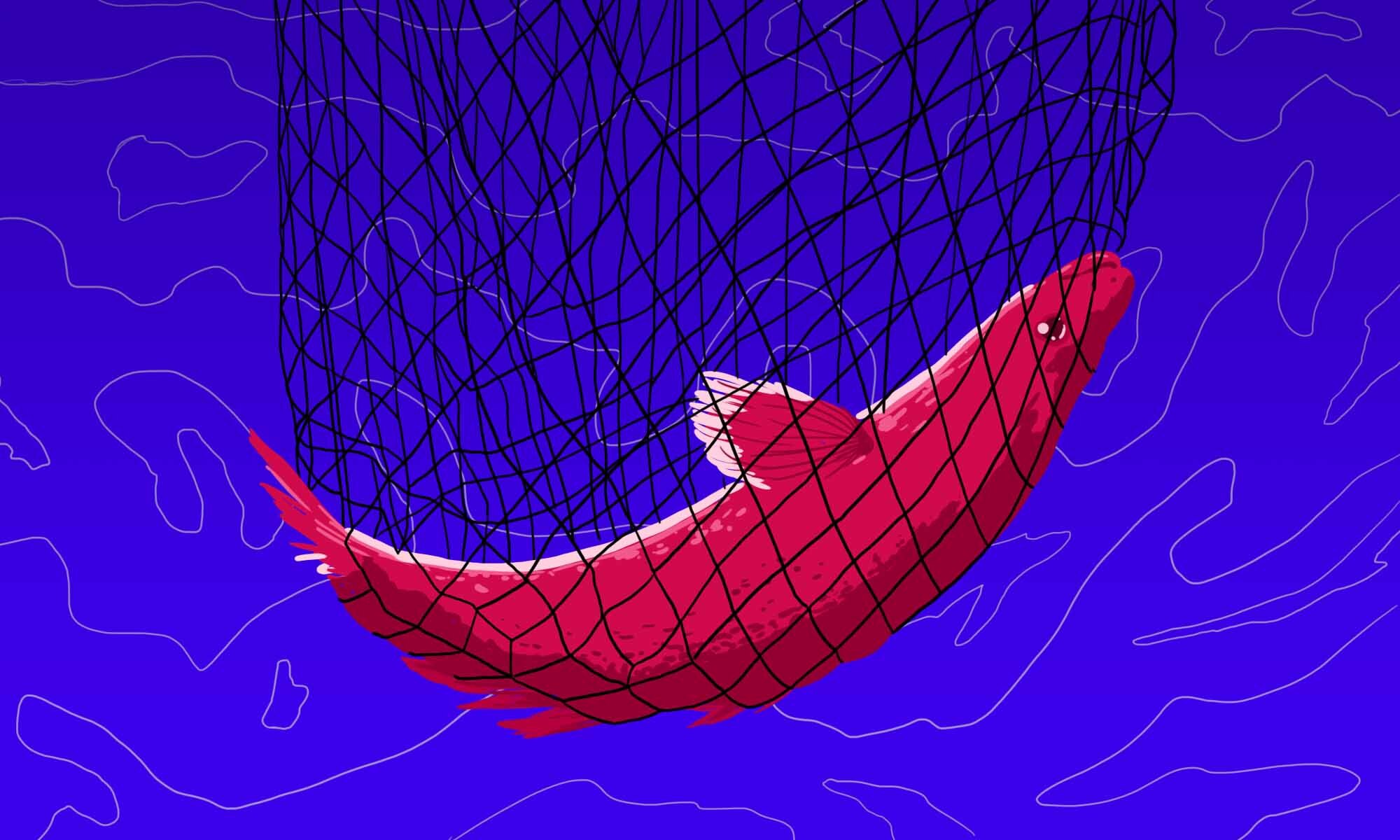

Every country with a distant-water fishing (DWF) fleet engages in illegal fishing, but China has the largest DWF fleet in the world. The recent presence of Chinese vessels off the coast of several South American countries has alarmed environmental authorities in the region.

In the final months of 2020, alarms went off in the Galapagos Islands and a big part of the Pacific coastline of South America, triggered by the presence of hundreds of fishing vessels, most of them Chinese, edging on their sovereign waters. The vessels’ presence has become a major diplomatic headache for several Latin American countries, as the ships are part of the Distant Water Fleets (DWF), a group of vessels fishing on the high seas in waters usually belonging to no country, but often near exclusive economic zones (EEZ).

Last November, the governments of Chile, Ecuador, Peru, and Colombia, the four members of the Permanent Commission for the South Pacific — a maritime organization that coordinates regional maritime policies — expressed their deep concern about illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing and with the presence of “a large fleet of foreign-flagged vessels.” (Chinese vessels weren’t specifically singled out.) To tackle this problem, measures were proposed by Ecuador were heard before the South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organization (SPRFMO), whose convention applies to the high seas of the South Pacific. This is an intergovernmental organization of 15 members — Australia, Chile, China, Cook Islands, Cuba, Ecuador, the European Union, Denmark, Faroe Islands, South Korea, New Zealand, Peru, Russia, Taiwan, and the United States — with interests in either the fishing industry or marine resources in the area.

At SPRFMO’s annual meeting from January 21 to February 3, delegates from Ecuador presented proposals for amendments to resolutions to forbid the use of transshipment — that is, ships resupplying and moving their cargo to bigger vessels in high seas — to restrict the delivery of vessels’ catch to authorized ports, and to increase the number of observers onboard of all Distant Water Fleets. According to the SPRFMO website, at least the proposal on transshipment was amended, and a declaration is now pending.

First, the Galapagos, and then south

The presence of Chinese ships was first detected off the coast of Ecuador in June 2020. A month later, the situation turned sour when the Ecuadorian government was informed that a foreign fishing fleet of about 260 vessels was stationed at the edge of the country’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) around the Galapagos Islands. That wasn’t the first time: In August 2017, the Ecuadorian Navy captured a Chinese vessel with 300 tons of fish illegally caught in the Galapagos, including endangered hammerhead and silky sharks.

In response to rising public concerns, Ecuadorian President Lenin Moreno announced the formation of a team of former political authorities in charge of a “protection strategy” of the Galapagos and the maritime resources of Ecuador. One of the team members, a former minister for the environment and former president of the World Wildlife Fund, Yolanda Kakabadse, stated in an interview that most of the ships around the Galapagos were Chinese.

“Because those are international waters, we have no capacity to forbid them and block their entrance,” Kakabadse said. [My expectation] is to have China as a conservation partner in the Galapagos-Cocos corridor. And why do I have this expectation? Because the Chinese people and government are also strategic in protecting their image.” Kakabadse pointed out that China will be hosting the UN Convention on Biological Diversity later this year.

In addition to establishing a “protection team,” Ecuador’s government met virtually with Chinese authorities to discuss the activities of the distant fishing fleet, first in August and again in December. The Chinese representatives from the Bureau of Fisheries of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the China Overseas Fisheries Association reiterated the will of their country to keep control over their vessels and to ensure they do not engage in IUU fishing activities.

In the meantime, then-U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo accused the Chinese ships near the Galapagos of frequently violating the sovereign rights and jurisdiction of coastal states, and fishing endangered and protected species without permission. The statement was immediately countered by the Chinese embassy in Quito, Ecuador, rejecting Pompeo’s accusations and reminding the U.S. that it had not ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. The nationalistic Chinese newspaper Global Times wrote: “As China has become more powerful on the ocean, the country’s normal, legal fishing operations have increasingly become a pawn that the U.S. uses to sow discord and incite conflicts with neighboring countries.”

Ecuadorian Minister of Defense Oswaldo Jarrín reported last month that satellite images detected, once again, Chinese vessels in the vicinity of the EEZ of the marine reserve area of the Galapagos archipelago. The suspected objective of the fishing fleet this time would not be giant squid, as it was during 2020, but coveted catch such as tuna and sharks.

While the Ecuadorian fishing saga was developing last September, Chinese ships were moving farther south into waters off the coast of Peru, prompting the Peruvian government and navy to publicly declare that they were surveilling the ships’ movements. Again, as it had previously done, Washington sounded the alarm on the Chinese flotilla. In response, Peruvian authorities called the U.S. to measure their words and to avoid spreading any “inconvenient inaccuracies.” (The Global Fishing Watch, an international nonprofit organization, warned last September that nearly 400 industrial foreign squid vessels flagged to China, South Korea, and Taiwan were fishing jumbo squid just off the edge of Peru’s EEZ, which, after anchovy, is Peru’s most important fishing product.)

Farther south, Chile — with more than 4,000 kilometers (2,500 miles) of shoreline and rich fishing ground off its coasts — was another country troubled by the closeness of Chinese vessels to its waters. In the middle of a ceremony to commemorate the 50th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Chile and China, the Chilean Minister of Foreign Affairs declared that Chile was “monitoring the situation” so that there would be no entry into its jurisdictional waters.

Until now, however, the country that has taken the strongest stance against Chinese fishing has been Argentina. Back in March 2016, the Argentinian navy sank a Chinese fishing vessel that entered its EEZ and illegally fished squid. Last April, a Chinese ship found fishing illegally inside the Argentinean EEZ paid a fine of around $400,000, plus another $247,000 for the merchandise it had onboard. One month later, the Argentinean navy captured two Chinese ships and a Portuguese vessel inside its EEZ. According to Argentinean authorities, in January 2021 there were already more than 100 ships in San Jorge’s Gulf, in waters outside Argentina’s EEZ, with more vessels expected to get to that area, most of them with a Chinese flag — but also South Korean, Spanish, and Portuguese ships in relevant numbers.

The alarm over Chinese fleets in particular has reached the national media in Latin America, and is followed closely by government officials.

The Chinese fleet

According to a June 2020 report from the UK-based research group Overseas Development Institute (ODI), China’s distant-water fishing fleet is the biggest in the world. It comprises nearly 17,000 vessels, with about 1,000 registered in other countries. The report indicates that during 2017 and 2018, Chinese vessels’ most frequented area was the Pacific Northwest, but that the most intense activities were focused in the Atlantic Southwest and Pacific Southeast — especially off the coast of Peru, in squid fisheries.

Dr. Dyhia Belhabib, Principal Investigator of Fisheries for the NGO Ecotrust Canada, states that Chinese fishing companies are a mix between state-owned, privately owned, and public-private joint ventures. As she explained in an interview with the National Committee on United States-China Relations (NCUSCR), in the case of the Chinese National Fisheries Corporation — which has the biggest Chinese distant fishing fleet — the state owns around 50% of the company.

China’s long-distance fishing fleet is probably the largest in the world, but as explained by Tabitha Mallory, founder and CEO of the China Ocean Institute, that is only a recent development. Speaking to NCUSCR, she said, “When the Soviet Union was around, they were the largest. Russia has since decreased the industry, but they’re increasing it again,” adding that Japan is still a big player, with Taiwan, South Korea, and Spain also playing an important role in the high seas fishing industry.

Interestingly, while China does sell its fleet’s catch to more developed markets like the European Union, Japan, or the United States, Mallory indicates that nowadays they are shipping a lot more back home. “They’ve started to build up a retail industry in China to market that seafood, and they also are importing a lot more due to an increase in consumers with more discretionary income and concerns about local food safety.”

Global problem and local response

According to a report published in 2018 by the journal Science Advances, without state subsidies for maintaining distant water fishing fleets, “high-seas fishing at the global scale that we currently witness would be unlikely.” The report detailed that “the largest subsidies are provided by Japan (US$841m) and Spain (US$603m), followed by China (US$418m),” and that five places — China, Spain, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea — contributed more than 85% of the fishing on the high seas.

After talks were repeatedly stalled during 2020, members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) restarted negotiations in January to end harmful fisheries subsidies. Another key issue in the discussion has been the establishment of exemptions for developing nations, an important point given China’s claim to be a developing nation, even when it is currently the second biggest economy in the world.

These negotiations come in the aftermath of a Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) report estimating that IUU fishing accounts for as much as one-seventh of the fish traded in the world, representing up to 26 million tons of fish caught annually, valued at between $10 billion and $23 billion. According to a 2020 FAO report, the fraction of fish stocks within biologically sustainable levels has decreased from 90 percent in 1974 to 65.8 percent in 2017.

A major issue for countries dealing with IUU fishing is that it is impossible to track fish origin: whether it was obtained in a legal area or by using abused labor. “Underreporting is a major issue, and not only for the Chinese fleet, but for every single distant water fleet I know of, including the European Union,” Belhabib said. She warns that China reports around 10% of its catch, but that at the same time, the EU fleet reports only 30%.

Distant water fishing operations affect local communities that rely on fisheries, potentially resulting in a reduction of their revenues, loss of jobs on shore, and more chances of conflict due to desperate responses by local fishermen and women. Belhabib says her research has found that coastal fishermen, especially in Latin America, are more likely to engage in illicit activities — from drug trafficking to illegal fishing — when their livelihoods are threatened.

Naturally, this is not exclusively a Latin American phenomenon. Mark Godfrey, a contributing editor to the fishing industry’s news website Seafood Sources, stated in an interview with the China Africa Project: “Fishing is a very complex and often very dirty industry, and there’s a whole web of companies.” Godfrey also states that Chinese fishing companies use the same mechanism with front companies. “Quite a lot of Chinese corporations, including fishing companies, operate from a mother ship in the British Virgin Islands.”

In the midst of regional tensions over high seas fishing, a key — though understated — factor is the possibility of local revenue enticing communities to support Chinese endeavors in exchange for jobs. There is a complex interconnection of international, public, and private interests here, with territorial, socio-economic, and environmental effects dependent on more than a single country’s actions. Be that as it may, with China being the biggest distant fishing fleet in the world, Beijing will be under more scrutiny. And if Chinese authorities and its fishing industry do not improve the transparency of its enterprise, it will continue to face hostility on the high seas.

SIX LARGEST CHINESE DISTANT-WATER FISHING FLEETS

- China National (Overseas) Fisheries Corp. (CNFC) / Zhong Yu Global Seafood Corp. / 中国水产总公司 / 中渔环球海洋 食品有限责任公司 / Location: Beijing; 257 ships

- Poly Group Corp. / Poly Technologies Inc. / Fuzhou Hong Dong Yuan Yang Pelagic Fishery Co. Ltd / 宏东渔业股份有限 公司 / 福州宏东远洋渔业有限公司 / Location: Beijing; 128 ships

- Fujian Province Pingtan County Heng Li Fishery Co. Ltd / 福建省平潭县恒利 渔业有限公司 / Location: Fuzhou, Fujian; 86 ships

- Dalian Chang Hai Yuan Yang Pelagic Fishery Co. Ltd / Dalian Chang Hai Ocean Going Fisheries Co. Ltd / 大连长海远 洋渔业有限公司 / Location: Zhong Shan, Dalian; 76 ships

- Rongcheng Rong Yuan Fishery Co. Ltd / 荣成市荣远渔业有限公司 / Location: Shandong; 68 ships

- China National Fisheries Yantai Marine Fisheries Corp. / Yantai Marine Fisheries Co. Ltd / 烟台海洋渔业有限公司 / 中国水产烟台海洋渔业公司 / Location: Shandong; 66 ships

Source: ODI report, base on FishSpektrum (2018).