China’s plans for ‘smart’ agriculture

The plans include ‘smart’ farms and machinery, agricultural industrial parks, and ‘digital villages.’ But can tech make up for extreme weather, diminishing agricultural land, and fewer people willing to work it?

A plan to take Chinese agriculture into the digital age

On Monday, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs issued new guidelines for the modernization of Chinese agriculture. The guidelines require that “digitalization demonstration zones” that use big data be fully implemented in three to five years. In essence, the Ministry wants Chinese agriculture to go digital, or to become “smart,” and these demonstration zones are the means to propel the digitalization process across the country. The zones are intended to facilitate deep integration of modern information technology with agricultural production, and in the process, to engineer rural revitalization.

The new guidelines build on a number of planning documents released in the last few years, including the Digital Agriculture and Rural Development Plan (2019–2025), released in 2020, and the 14th Five-Year Plan for Promoting Agricultural and Rural Modernization, released by the State Council earlier this year. The latter plan proposed the construction of “digital villages” — with advanced information and communication infrastructure in rural and remote areas — and modern agricultural industrial parks.

The new guidelines specify four key elements for taking Chinese agriculture into the digital age:

- Expanding information infrastructure in rural areas, including 5G network coverage and fiber internet access.

- Promoting the use of data, especially county-level agriculture big data systems.

- Digitalization of the agricultural industry chain, including “smart” production, processing, and circulation at “smart farms” making use of the Internet of Things, big data, artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and 5G.

- Expanding digitalization, including cloud-based services, tracing of agricultural products, digital mapping of farmland, remote monitoring systems, and water-saving irrigation.

“Smart machinery” and “smart farms”

Another component of “smart” agriculture will be “smart” agricultural machinery. Yesterday, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) held a press conference about the current state of development of “smart” agricultural machinery in China. According to the MIIT, the mechanization rate of crop cultivation and harvesting in China increased from 57% in 2012 to 72% in 2021, and is expected to reach 75% by 2025. China’s agricultural machinery product classification system now contains 65 categories and around 4,000 models, including 5G hydrogen fuel electric tractors, multi-functional combine harvesters, and six-row cotton pickers.

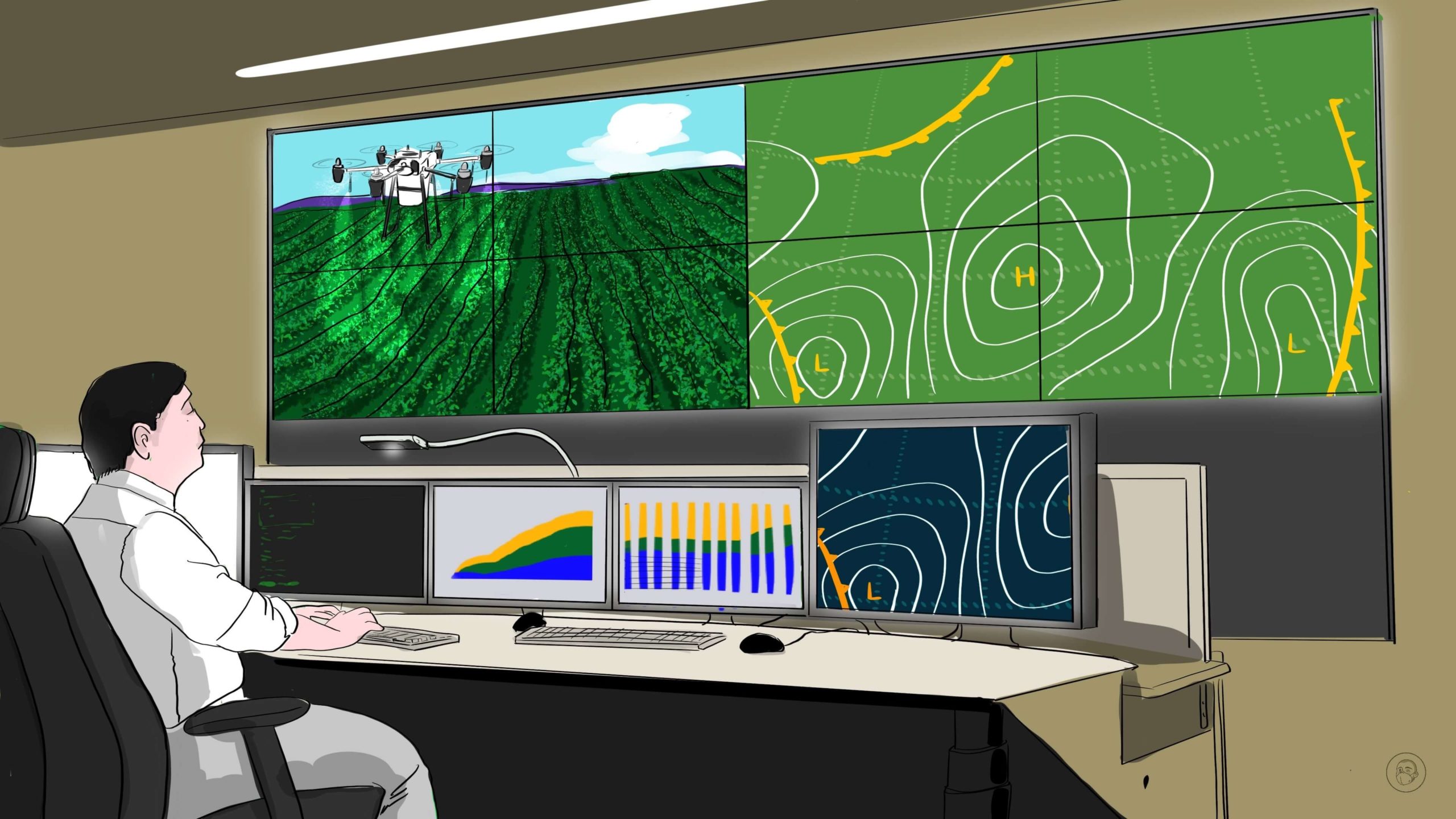

There are already various “smart farms” in operation in China. For example, on Monday, Chinese media reported on a 1,647-acre rice farm in a “Science and Technology Demonstration Park” in Heilongjiang Province in northern China. The farm has what looks like a command and control center with big screen displays of drone footage of the entire farm along with various digital indicators, and an array of monitoring equipment and greenhouses located in the farmlands. The reports say that the farm utilizes modern information technology such as the Internet of Things and cloud computing to manage rice seed germination, greenhouse operations, and water-saving irrigation. The tech also allows for comprehensive monitoring of meteorological information and data about diseases, insects, and weeds.

The new guidelines released by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development are intended to increase the number of such farms across the country.

Pressure points: Land and people

While the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs may have big plans for modernizing Chinese agriculture, an official from the Ministry this week explained the challenges to achieving this.

The first problem is cost: While there are already various high-tech demonstration centers in operation, the cost of installing new technology is high.

The second issue is the gradual decrease in the rural workforce due to migration and aging. In 2021, there were a total of 292.51 million migrant workers in China, 171.72 million of whom were from rural areas — in other words, the rural workforce is going urban.

The third challenge is the decrease of arable land. According to a report by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs released in January this year, the amount of cultivated land in China decreased from 2.03 billion mu (334.41 million acres) in 2012 to about 1.92 billion mu (316.29 million acres) in 2021. In addition, the report also mentions the problems of urbanization, environmental damage, and the increasing cost of land.

But perhaps the greatest and least predictable challenge of all is extreme weather, as even the smartest farms and machinery cannot operate well in tornadoes, record-breaking rainfall, drought, and scorching heat waves.