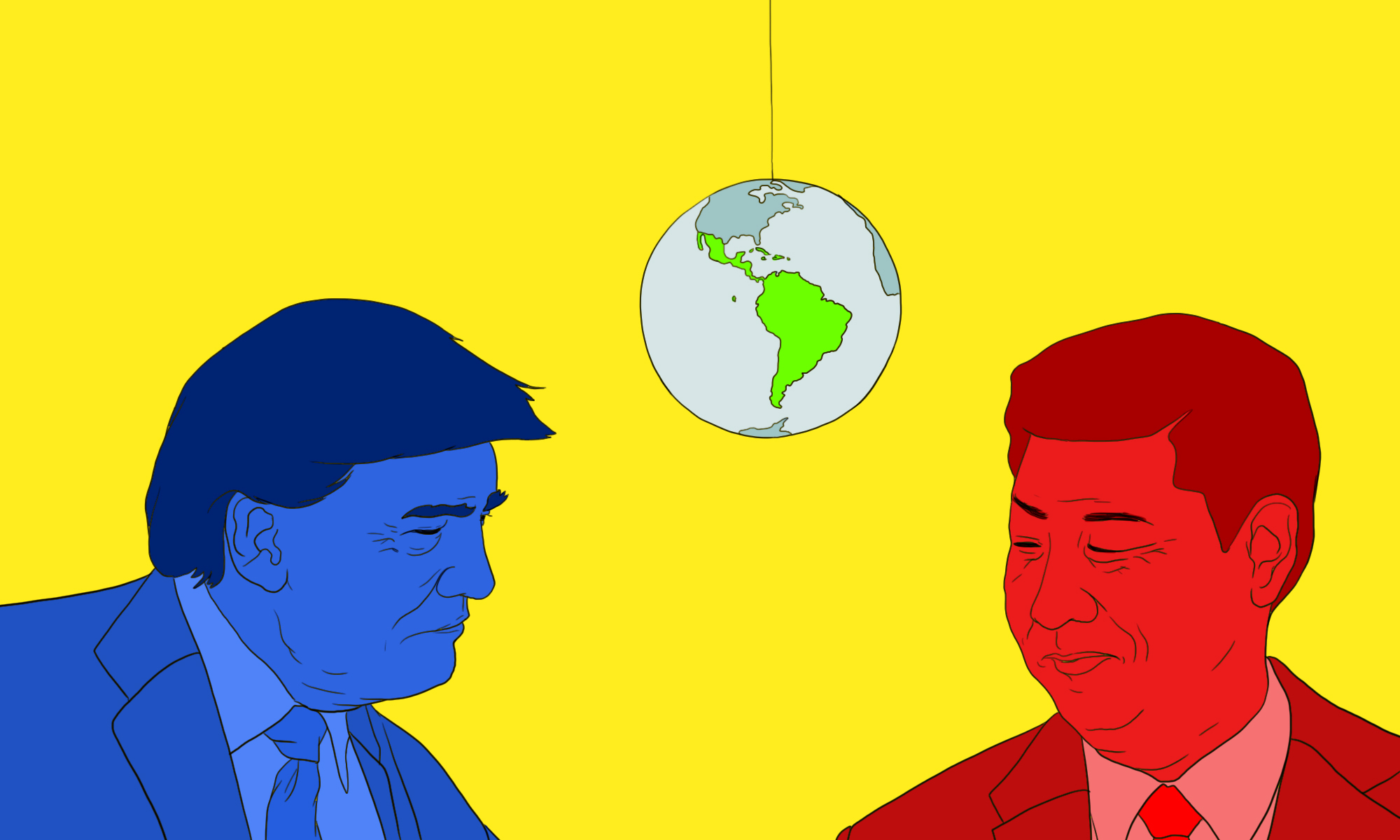

Amid U.S.-China conflict, can Latin America find its way?

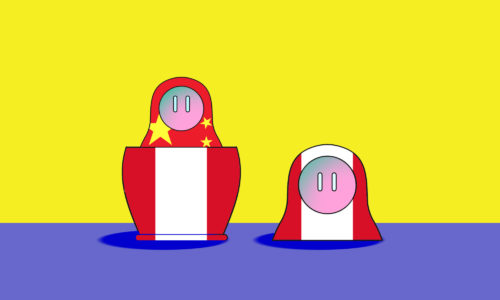

Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) countries have found themselves caught in the middle of the U.S.-China trade war, with no unified strategy as to how to move forward.

At the beginning of 2020, with the signing of the “Phase One” trade deal, there was hope that tensions between China and the U.S. would diminish. Washington promised to reduce tariffs on Chinese goods, while Beijing committed to buying more American goods and services.

But this goodwill evaporated upon the arrival of COVID-19 in the U.S. Trump searched for a scapegoat for his administration’s inability to contain the pandemic, and thus, “Chinese virus” was born. Beijing responded to Trump’s rhetoric in kind.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world has watched — with many trying to avoid becoming collateral damage in this spat between giants.

For Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) governments, it has become all but impossible to ignore the consequences of Washington’s sanctions on Chinese firms such as Huawei — which has a great presence in the region — or the addition of firms such as China Communications Construction Company (which keeps several projects in LAC countries) on the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Entity List.

Just recently, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo reiterated the Trump administration’s stance on China when he briefly visited four countries in South America (Guyana, Suriname, Colombia and Brazil).

In Suriname, Pompeo warned the local government about Chinese investment: “We’ve watched the Chinese Communist Party invest in countries, and it all seems great at the front end and then it all comes falling down when the political costs connected to that becomes clear.” Meanwhile, Suriname’s newly elected president, Chan Santokhi, said in the same press conference, “As regards the position of China and this relation, I can inform you clearly that this was not a topic of the agenda. It was not a topic of our discussion. So, it is not a question of making choices.”

The Chinese embassy in Suriname simply replied: “We advise Mr. Pompeo to respect facts and truth, abandon arrogance and prejudice, stop smearing and spreading rumors about China.”

Can LAC countries actually cooperate?

Do LAC countries have any alternative?

In an article published by Foreign Affairs Latinoamérica, Chilean ex-diplomats assert that LAC could adopt “active non-alignment,” which was used during the Cold War when Washington butted heads with Moscow. But the authors warn that “the difference is that, this time, the stakes from an economic point of view are much higher, given the size of the Chinese economy and its considerable presence in the [LAC] region.” The Soviet Union had no such comparable presence.

This past August, “active non-alignment” was discussed in a seminar with the virtual presence of six former foreign ministers from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru.

Celso Amorim, former Brazilian foreign minister under President Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, indicated that throughout Lula’s administration, Brazil sought to exercise a strategy that privileged its own interests over those of the United States and other foreign powers. According to Amorim, Lula’s administration unambiguously said no to everything that did not serve Brazilian national interests. “We said no to the FTAA [Free Trade Area of the Americas, promoted by the United States] when we were not interested, we said no to a bad agreement that was to be signed at the World Trade Organization meeting in Cancun, 2003, we contributed to the creation of other forums, and in some, we participated with Argentina and Mexico…that was our position,” Amorim said, pointing out that, to some extent, it is possible to navigate around the political interests of global superpowers.

Mexico’s former foreign minister under President Vicente Fox, Jorge Castañeda, stated that under the current circumstances, he understands the reluctance of LAC countries to align themselves with the U.S. But, he added, there are also good reasons not to get too close to China, either. “Some say that it’s good there are no conditions imposed, for example, in Chinese aid, trade and investment, because that respects the principle of non-intervention. To that I say the opposite, I don’t think it’s good at all. I prefer a thousand times over the conditions established by the World Bank in areas such as labor, the environment, gender, indigenous peoples, children, etc.”

Castañeda said the U.S. is an open and democratic society, one that Latin Americans know well, and one in which, to some degree, they can influence. On the other hand, “In the opacity of Chinese society, of Chinese political power, to say it bluntly, of the Chinese dictatorship, our possibilities of influence inside China are practically nil.”

Coordinating a regional stance as it pertains to China and the U.S. requires cooperation, but the present state of affairs in the LAC region isn’t conducive to such teamwork.

“The level of mutual trust among governments is rather low, and it also changes frequently,” said Chilean lawyer Manfred Wilhelmy, a specialist in Asia Pacific affairs. Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro and Argentinian president Alberto Fernandez, for example, don’t even talk to each other due to ideological differences.

The lack of broad regional communication and dialogue is also reflected in the weaknesses of LAC’s historically multilateral organizations, such as the Rio Group, UNASUR, and CELAC. Nicole Jenne, a researcher at the Center for Asian Studies of the Catholic University of Chile, said that it is unlikely for these organizations to regain their former status. “I do not believe that any of these institutions can fulfill this role in the current circumstances,” she said. She also sees the Forum for the Progress and Development of South America (PROSUR) as “a short-term initiative of (center) right governments.”

Jenne said that it is noteworthy that Chile, “in an attempt to develop a political strategy toward China, seeks to exchange information and find common ground with what it calls ‘like-minded countries’: Australia, New Zealand, occasionally Nordic countries. It is not even looking for dialogue within the region.”

Chile’s recent decision regarding the sea route for what will be the first submarine transpacific fiber-optic cable to connect South America with Asia reflects this way of thinking. Although the original plan was conceived by the governments of Chile and China to link the two countries by an undersea cable, Santiago eventually opted for a Japanese proposal that designated Sydney as the end point of the fiber optic line. For such a drastic change, Chilean authorities emphasized the benefits of choosing Australia, itself connected to Asia through several underwater cables, and made no mention of political pressures by the United States to discourage the use of Huawei products, which was one of the parties supporting the original plan that had Shanghai as the end point in Asia.

How are other regions reacting to the pressures arising from U.S.-China clashes?

The experience of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), a multilateral 10-country organization in southeast Asia, could serve as a case study for Latin American leaders. The reason is simple: ASEAN has long been dealing with pressure from Washington and Beijing, both trying to turn the regional balance in favor of their own objectives, involving much more sensitive issues than those discussed so far in LAC.

Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Brunei do not accept China’s vast territorial claims based on its nine-dash line. They have the support of the United States, which argues that it is protecting freedom of navigation through the disputed waters, an area crucial for international trade. At the same time, ASEAN members that reproach Beijing cannot afford to entirely back Washington and risk antagonizing the region’s most important trading partner. (On the other hand, China also has firm allies, such as Cambodia.)

The most recent annual meeting of ASEAN in early September, with the presence of Washington and Beijing, only reaffirmed the persistence of the tensions, now exacerbated by the U.S.-China trade war. Chinese Foreign Minister Wáng Yì 王毅 pointed out during the meetings that the U.S. was the “biggest driver” of militarization in the South China Sea. In turn, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declared in one of the virtual gatherings that regional governments should “reconsider business dealings with the very state-owned companies that bully ASEAN coastal states in the South China Sea.”

In an interview ahead of the meetings, Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi warned the U.S. and China: “ASEAN, Indonesia, wants to show to all that we are ready to be a partner…We don’t want to get trapped by this rivalry.” Subsequently, that message was echoed at the end of the summit by the Deputy Prime Minister of Vietnam, Pham Binh Minh, who stated that ASEAN countries did not want to be “stuck in the competition between the major powers as that would affect peace and stability in the region.”

Although the dilemmas facing ASEAN and LAC are, at least currently, of a different magnitude, when it comes to dealing with diplomatic squabbles between China and the U.S., Southeast Asia has had a solid multilateral platform to state its point of view, from which it can build a position with the support of its members. This is clearly absent in LAC, for now.

RELATIONS BY THE NUMBERS

According to statistics by the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC):

- LAC’s trade in goods with the United States in 2019 reached $535.7 billion. This represented 21.7% of U.S. total trade.

- The top U.S. trading partners in the region in 2019 were Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, and Chile; together they represent 83% of total trade in goods with Latin America and the Caribbean.

- Trade with Mexico represented 68% of total trade with Latin America and the Caribbean.

According to a report by the BU Global Development Policy Center:

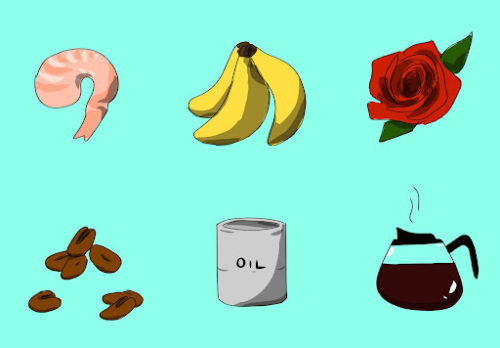

- LAC trade with China in 2019 reached $303.2 billion.

- The region exported $141.5 billion in goods to China and imported $161.7 billion in Chinese goods.

- LAC exports to China continue to be concentrated in a few raw commodities, particularly soybeans, copper, petroleum, and iron.

- For soybeans in particular, the China-U.S. trade dispute has spurred a major South American boom, particularly in Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay, as Chinese importers have gone away from U.S. producers.