China curtailed loans to Latin America in 2020. Will the U.S. swoop in?

In 2020, loans from Chinese policy banks in Latin America fell to historically low levels. In the last days of the Trump administration, Washington agreed to lend Ecuador $3.5 billion, in what U.S. authorities considered a novel approach to confront China in the region. But does the region stand to benefit?

According to a recent joint investigation by Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center (GDPC) and the Inter-American Dialogue, in 2020, for the first time since 2006, China did not offer new financing commitments to the governments of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC).

And then, at the beginning of 2021, the United States reached a surprising financial agreement with Ecuador, this after largely ignoring LAC for several years.

In the last days of the outgoing administration of Donald Trump, the Ecuadorian government announced that it signed an agreement in Washington, D.C. with the International Development Financial Corporation (DFC) of the United States to receive financing for $3.5 billion, funds that would replace debt commitments already acquired, this time supposedly with better conditions for Ecuador.

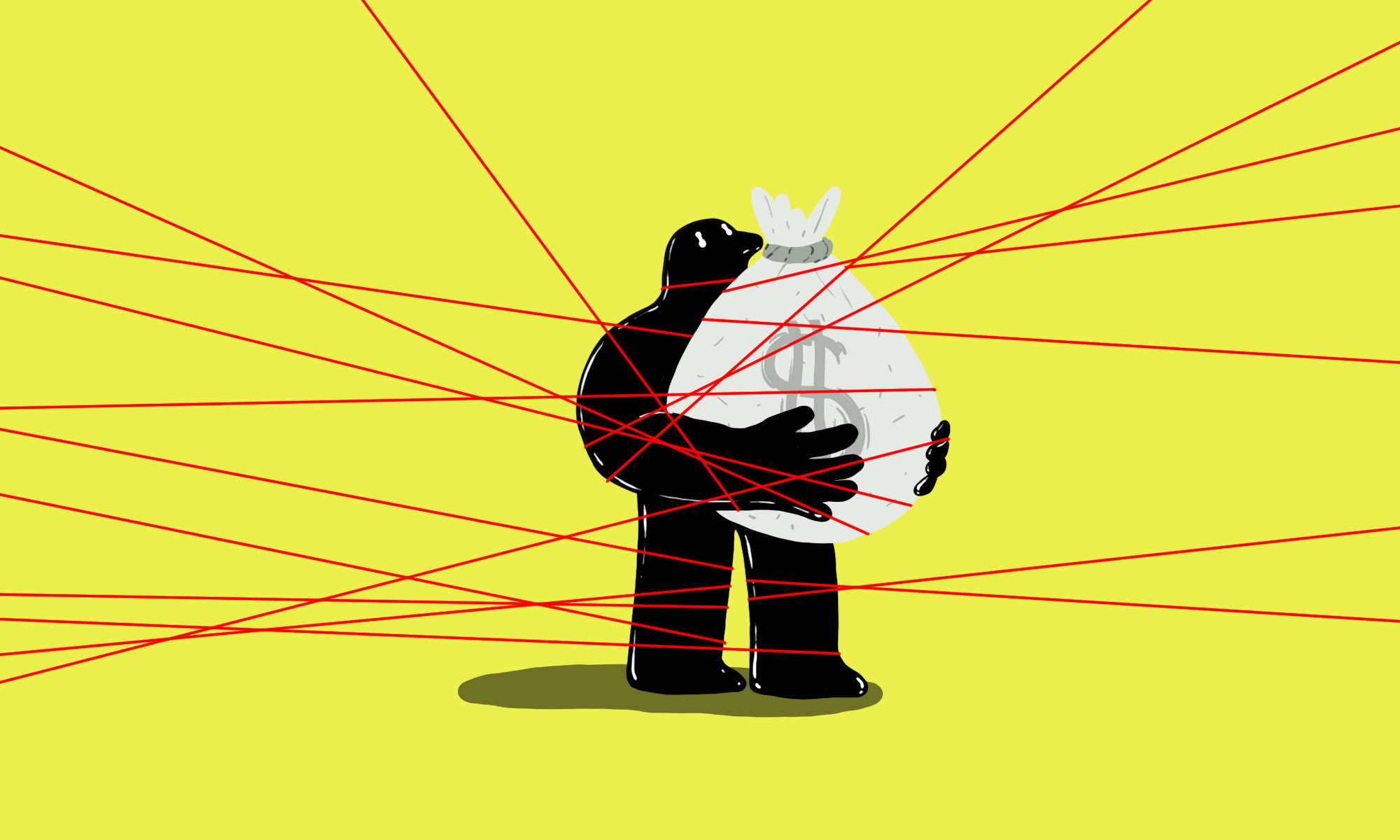

Although China is not mentioned in the agreement, the executive director of the DFC, Adam Boehler, stated bluntly in a press release: “This framework agreement allows DFC to streamline support for projects that refinance predatory Chinese debt and help Ecuador improve the value of its strategic assets.”

Speaking to the Financial Times, Boehler explained what he considered were the virtues of the agreement:

“It is a novel approach that very strongly combines both missions of the DFC. The first is that we are going to impact development in Ecuador in a very positive way,” Mr. Boehler told the Financial Times. “DFC was created so that no single authoritarian country had undue influence over another country and we are addressing that factor with this agreement.”

The Trump administration hopes that the agreement will provide a template that will encourage other nations to wean themselves off Chinese debt and remove Chinese telecoms companies from their networks.

[…] One of the main conditions of the deal with Ecuador is that Quito signs up to what the Trump administration calls “The Clean Network” -a state department initiative designed to ensure that nations exclude Chinese telecoms services and equipment providers as they build out their high-speed 5G mobile networks.

Alas, the agreement offered by the DFC could have negative consequences on the economy and the environment of Ecuador. In a column published by The Hill, Jorge Heine (a former Chilean ambassador to China and professor at Boston University) and Kevin Gallagher (director of the GDPC) point out that the agreement obliges Ecuador to privatize oil and infrastructure assets, in addition to banning Chinese technology in the country.

“As we expected from the Trump administration, the DFC’s decision was bad development policy, bad policy toward Latin America, and bad policy toward China,” the authors write. “Fortunately, the Biden administration can reverse it as it seeks to repair America’s world position and vision for global prosperity.”

Heine and Gallagher agree that China’s loans to Ecuador have problems, but they also argue against the option offered by the U.S.:

The DFC deal curtails state capacity while generating windfall profits for U.S. fossil fuel interests. What’s more, the move would further lock the country into fossil fuel and extractive production and would ban the country from accessing cutting edge technologies.

Their column ends with the hope that the Biden administration will modify the agreement with Ecuador in a way that helps build a clean economy that creates jobs, and which can serve as a positive example of U.S. foreign policy in LAC.

For now, it remains to be seen what path Biden will take in the region. However, considering that the DFC deal pretends to use large-scale privatization of public assets — which under the Washington Consensus in the 1980s and 1990s had painful consequences for the most vulnerable people in LAC — Biden should consider changing the deal with Ecuador.

If the long-term goals of agreements pushed by U.S. loans and investment in LAC don’t consider the lessons of the past and the need for long-term economic growth, Latin American governments will probably continue to look to Beijing for better options.