Introduction by Jeremy Goldkorn, The China Project Editor-in-Chief

What to expect in 2022, Year of the Water Tiger

History won’t repeat itself, but it will probably rhyme.

The Year of the Water Tiger begins on February 1, 2022. The Chinese animal zodiac is a 12-year cycle — when you add the element (wood, fire, earth, metal, or water), you get a 60-year calendar, so the last Water Tiger year was 1962.

That year, the Seven Thousand Cadres Conference (七千人大会) took place in Beijing, when Party officials gathered from late January to early February, and discussed the disastrous famines of the Great Leap Forward that began in 1958. Chairman Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 made a self-criticism at the conference and then took a step back from power. (That proved to be temporary.)

In March 1962, senior leader Chén Yún 陈云 began promoting the idea that China’s economy should be “balanced” — that the market had a role to play alongside the Party. Chen was denounced as a “capitalist roader” (走资派) when Chairman Mao made his comeback in 1964 and launched the Cultural Revolution, but Chen’s ideas formed the basis of the “socialist market economy” that Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平 made into a reality after 1978, which created the China we know today.

The year 1962 was also the year of the Sino-Soviet split — when Beijing and Moscow broke off relations partly because of the Cuban Missile Crisis, a monthlong standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union. That year, India and China fought a brief war on their Himalayan border — a dispute that has not yet been properly resolved.

Far away from the mountains of Central Asia, in 1962 in the U.S., the first Spider-Man comic was published, and the first Wal-Mart store opened. That year also saw one of history’s most successful vaccination campaigns with the U.S. rollout of an oral vaccine against polio, and Congress passing the Vaccine Assistance Act, which gave money to states for vaccination programs against polio, diphtheria, whooping cough, and tetanus.

I have no belief in any predictions based on astrology, Eastern or Western, but I expect 2022 to be as momentous a year for China as 1962 was. On the other hand, star signs are probably about as accurate a way of forecasting the future as any other method.

In that spirit, then, below are my predictions for 2022. (You can see the forecast for 2021 I made a year ago here and check my track record.)

Predictions for 2022

We can anticipate a year, like 1962, of changes and conflicts, and the formation of political and economic trends that will shape the decades to come. These may include:

Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 will be anointed as China’s leader for a third term at the Party’s 20th Congress in the fall of 2022. Barring a medical problem, Xi will be the party-state’s essential commander-in-chief for the next decade, with unquestioned control of the Chinese Communist Party, People’s Liberation Army, and all organs of state power.

China will maintain a COVID-zero policy until the fall of 2022. The Party will likely have little tolerance for risk until Xi enters his third term, which means tight restrictions on incoming international travelers. Imports of consumer products and domestic travel restrictions will come and go, sometimes because of legitimate worries about the virus, and sometimes because the biosecurity state is now a reality.

“Common prosperity” will remain a cornerstone of Xi Jinping’s policy priorities, as it has during 2021. Implementing it will include ongoing campaigns against labor and market abuses by tech and real estate companies, punishments and inducements to ensure the wealthy pay taxes and put money into social programs, a wide-ranging effort to make the education system more egalitarian, and crackdowns against “immorality” and perceived moral laxity in the entertainment industry.

The economy will slow down drastically as the country reshuffles its economic machinery by deflating its real estate sector and reinvesting in sectors that drive “stable growth.” Meanwhile, demographic problems such as a declining birth rate and a shortage of skilled labor mean the coming year will likely see a more stagnant economy.

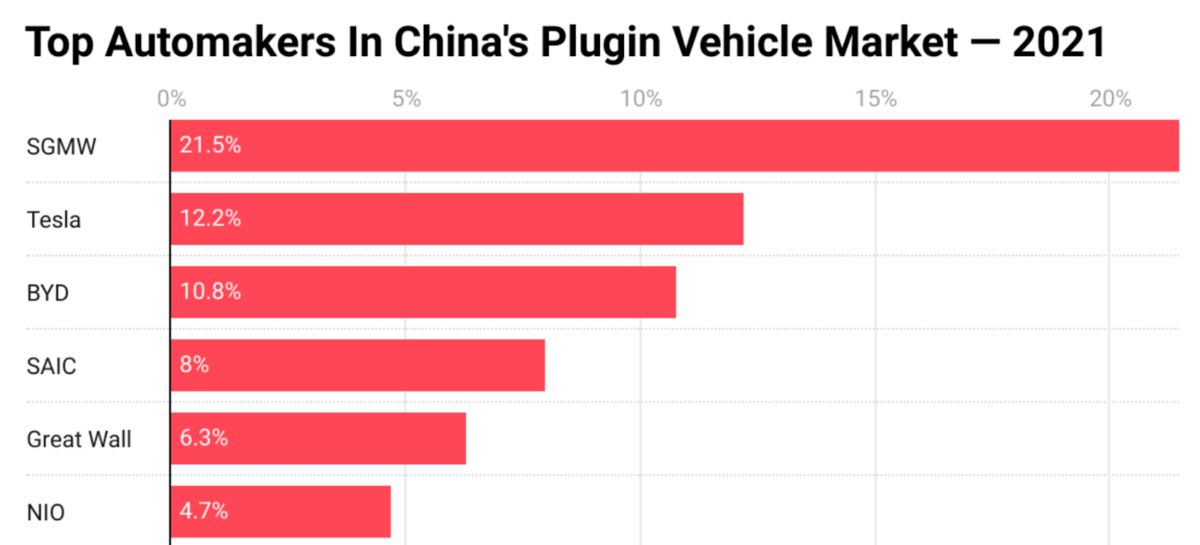

The electric car industry will consolidate and expand further into Europe. In Norway, where around 80% of new cars are already electric, Chinese brands will dominate. From there, the Chinese EV companies will make serious inroads into the market in the rest of Europe. As European countries wake up to this reality, there will be loud calls for banning Chinese EVs or for closely monitoring their use of data. Meanwhile, at home, a flood of mergers and acquisitions will begin as losers of China’s oversaturated EV race get pruned.

Beijing will enact ever-more-invasive policies around reproduction, including restrictions on vasectomies and abortions — all while remaining scornful of surrogacy and assisted reproductive technologies such as IVF and egg freezing. All of this is part of an effort to persuade China’s women to have more babies and avert a demographic time bomb, but without compromising the traditional notions of family endorsed by the government.

Another Péng Shuài 彭帅 will emerge, or a few, as feminism and the #MeToo movement grow in influence. Despite government attempts to muzzle civil society voices advocating for gender equality and women’s rights, social media will remain an important platform for women to increase visibility of ongoing issues they face and potentially inspire change.

More high-profile Chinese tech companies will delist from U.S. stock markets, or undergo restructuring to spin off sensitive data divisions. These may include ecommerce giant Pinduoduo, the ride-hailing startup Full Truck Alliance, and possibly even EV companies like NIO or Xpeng. The regulatory pressures that felled Didi this year are only growing as Beijing implements a hard-line stance on data sovereignty and the use of algorithms. The government will push for a total localization of its technology stack, and aggressively ramp up investment in chokepoint technologies like silicon chips.

China will intensify diplomatic contact with countries in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. With some of the most important minerals of the global economy stored in these countries, there will be more infrastructure projects and loans and trade between China and the rest of the developing world than ever before, despite much criticism in the media.

Newly emerging Chinese brands will beat out foreign competitors. With this year’s rows over Xinjiang cotton and decoupling of supply chains, the phenomenon of “market nationalism” is stronger than ever. Chinese are already wearing Li Ning instead of Nike, buying Huawei instead of Apple, and drinking Genki Forest instead of Coke. Other consumer categories, including fashion, cosmetics, and fast food, are likely to see new national leaders usurp their foreign counterparts.

The U.S. and China will remove a few insignificant tariffs on Chinese imports, but the economic and political relationship will remain tense.

Russia will invade Ukraine; China will offer silent support. The lack of an American response will embolden hawkish Chinese voices on Taiwan but not lead to any kinetic action.

There will be no major confrontation in the South China Sea, but it will remain a geopolitical flashpoint. This could all change in the event of an accident or incident involving military ships or planes in the Taiwan Strait, or a fishing vessel conflict, or some other unplanned disaster that affects China’s relations with Taiwan, Japan, the U.S., Korea, or a Southeast Asian country.

Beijing will have to respond to a dramatic terrorist incident in Pakistan or Afghanistan that involves Chinese cititzens or interests. Tensions on the Indian border will fester.

There will be protests connected to the Winter Olympics and against China’s policies in Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Tibet. Despite these and the “diplomatic boycott” from the U.S. and other countries, the Games will go smoothly on TV and no athletes will protest.

A senior German official will be accused of “hurting the feelings of the Chinese people.”

The Hong Kong government will begin erecting a version of the Great Firewall to censor the internet.

Thanks to Chang Che, Jiayun Feng, and Geremie Barmé for talking through these with me, but the forecasting errors will be all my responsibility.

campuses with a Häagen-Dazs ice cream cone or a bottle of Coca-Cola in hand. Today, young Chinese prefer the taste of

campuses with a Häagen-Dazs ice cream cone or a bottle of Coca-Cola in hand. Today, young Chinese prefer the taste of  China is one of the largest consumer economies in the world, and a hungry middle class begets new consumer brands. In 2021, one unexpected impact of the pandemic was the disruption of global supply chains, crunching multinational businesses but also breathing new life into Chinese companies serving Chinese customers.

China is one of the largest consumer economies in the world, and a hungry middle class begets new consumer brands. In 2021, one unexpected impact of the pandemic was the disruption of global supply chains, crunching multinational businesses but also breathing new life into Chinese companies serving Chinese customers.